It's time to go back to High-Low's roots on TCJ, and that's reviewing minis I get at the various comics festivals I've attended. This month's batch encompasses a period of a couple of years and a lot of ground covered.

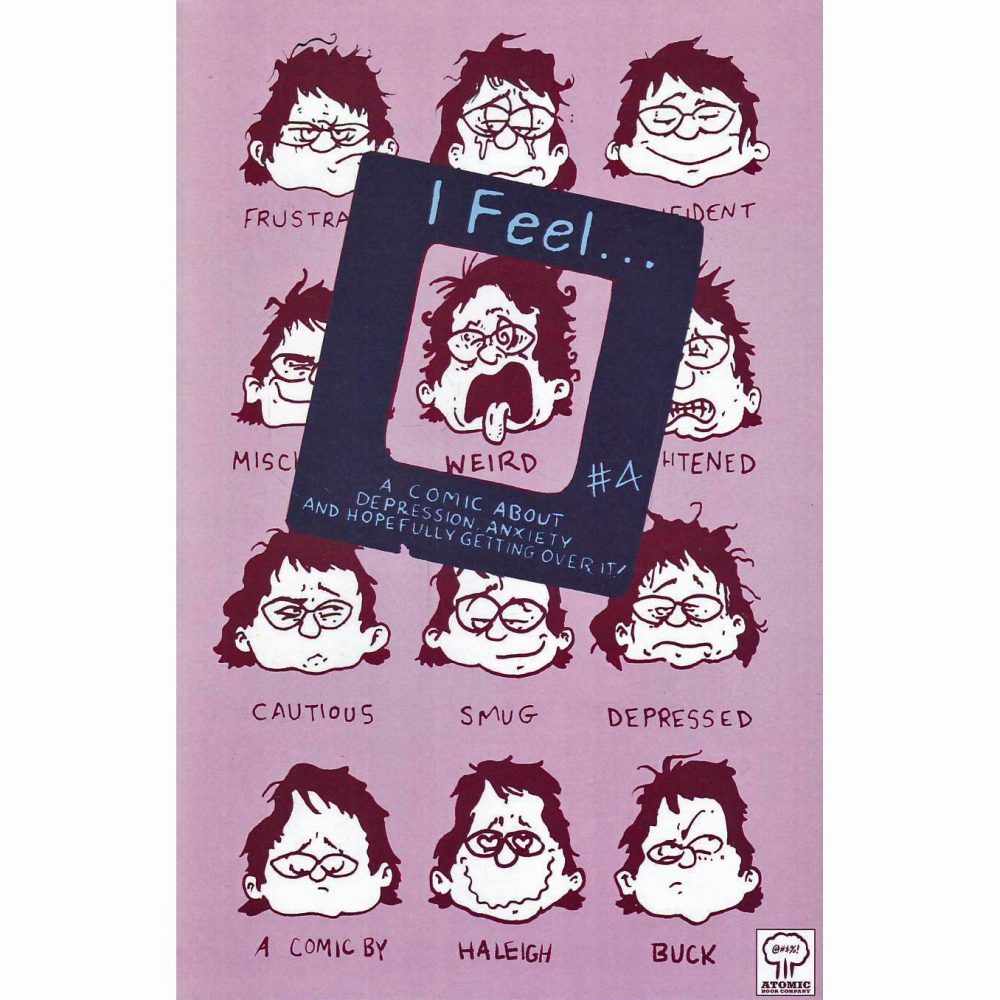

I Feel Weird #4, by Haleigh Buck (CAKE, 2019). Buck's scribbly, dense, and occasionally claustrophobic autobio comics about mental illness are real and raw. This series has seen her alternate between accounts of panic attacks and therapy sessions with the history of mental illness and its various treatments. Buck somehow wound up with a weird, faith-based therapist who frequently got her name wrong and gave her bizarre treatment assignments like cutting out paper dolls. She was supposed to blame them for her bad feelings.

I Feel Weird #4, by Haleigh Buck (CAKE, 2019). Buck's scribbly, dense, and occasionally claustrophobic autobio comics about mental illness are real and raw. This series has seen her alternate between accounts of panic attacks and therapy sessions with the history of mental illness and its various treatments. Buck somehow wound up with a weird, faith-based therapist who frequently got her name wrong and gave her bizarre treatment assignments like cutting out paper dolls. She was supposed to blame them for her bad feelings.

Buck's research into the history of therapeutic drugs is meticulously researched and thoughtful, which put it into stark relief with the concurrent story she was writing about trying to get her therapist to approve her disability. Buck's narrative is as much about how a person without means has to negotiate bureaucracies as it is about her own anxiety. Speaking of which, a strip about a trip to the grocery store was written like a Civil War soldier's epistle to their wife at home. The florid prose revealing the horrific anxiety that being in a crowded public place is aimed at Buck's dog. What makes these comics so effective is Buck's ability to write and draw in an immersive fashion, plunging the reader into her mindset. At the same time, Buck's ability to sometimes write about herself from a distance allows her to joke about her circumstances while adding clarity as to exactly what's happening.

Buck's research into the history of therapeutic drugs is meticulously researched and thoughtful, which put it into stark relief with the concurrent story she was writing about trying to get her therapist to approve her disability. Buck's narrative is as much about how a person without means has to negotiate bureaucracies as it is about her own anxiety. Speaking of which, a strip about a trip to the grocery store was written like a Civil War soldier's epistle to their wife at home. The florid prose revealing the horrific anxiety that being in a crowded public place is aimed at Buck's dog. What makes these comics so effective is Buck's ability to write and draw in an immersive fashion, plunging the reader into her mindset. At the same time, Buck's ability to sometimes write about herself from a distance allows her to joke about her circumstances while adding clarity as to exactly what's happening.

Presenting "Precious Rubbish" and All True Romance, by Kayla E. (Zine Machine, 2019). The first comic is a "Rotland Single Shot" from Ryan Standfest's Rotland Press. It's a high-end minicomic, essentially. Kayla E. is a cartoonist, writer, editor, and designer whose character work is somewhere between John Stanley and Mark Newgarden. She perfectly captures the lively qualities of the former and the grotesque qualities of the latter with her big-nosed and blank-eyed self-caricature. In a series of short vignettes, Kayla E. tells stories about being rejected by her family for being a lesbian, her alcoholism, and a heart-rending account of being asked to look for spare change at the supermarket as a kid in order to buy a loaf of bread. All of this is done with the rhythm of gag strips. It's a relentlessly bleak yet visually upbeat collection of strips, and it's that tension that makes them so memorable.

Presenting "Precious Rubbish" and All True Romance, by Kayla E. (Zine Machine, 2019). The first comic is a "Rotland Single Shot" from Ryan Standfest's Rotland Press. It's a high-end minicomic, essentially. Kayla E. is a cartoonist, writer, editor, and designer whose character work is somewhere between John Stanley and Mark Newgarden. She perfectly captures the lively qualities of the former and the grotesque qualities of the latter with her big-nosed and blank-eyed self-caricature. In a series of short vignettes, Kayla E. tells stories about being rejected by her family for being a lesbian, her alcoholism, and a heart-rending account of being asked to look for spare change at the supermarket as a kid in order to buy a loaf of bread. All of this is done with the rhythm of gag strips. It's a relentlessly bleak yet visually upbeat collection of strips, and it's that tension that makes them so memorable.

All True Romance uses her witch (Petra) and nun (Charley) characters as stand-ins for herself and her wife Laura. As acidic and emotionally distant as Precious Rubbish is, this comic is warm, sentimental, and vulnerable. Meeting on a bus from New York to Boston, they notice each other's quirkiness and over a period of years finally decide to get together. This is a comic about leaps of faith, unlikely meetings, and the ways in which people can grow together. The use of that Stanley style of character types here serves a different purpose: it allows Kayla E. to cut through the deeply personal sentimentality of the story with the funny look and tone of the character design. Here, the tension works in a different way, as the silliness of the characters and fairy tale tone is balanced against the deadly seriousness of this relationship.

Viewotron Comics And Stories No. 1, by Sam Sharpe and Peach S. Goodrich (AdHouse edition, Zine Machine 2019). This is a collection of some stories from the earlier, self-published editions plus some new material. Sharpe & Goodrich, along with Hartley Lin, Josh Pettinger and others, represent a new wave of short story specialists. Sharpe and Goodrich do solo stories but also collaborate, like a quick story called "The Secret Origin Of The Viewotron" that's written by Sharpe and drawn by Goodrich. That in itself is a story about collaboration and the ways in which an idea can be taken and improved upon by someone else to the point where it outlasts the original project.

Viewotron Comics And Stories No. 1, by Sam Sharpe and Peach S. Goodrich (AdHouse edition, Zine Machine 2019). This is a collection of some stories from the earlier, self-published editions plus some new material. Sharpe & Goodrich, along with Hartley Lin, Josh Pettinger and others, represent a new wave of short story specialists. Sharpe and Goodrich do solo stories but also collaborate, like a quick story called "The Secret Origin Of The Viewotron" that's written by Sharpe and drawn by Goodrich. That in itself is a story about collaboration and the ways in which an idea can be taken and improved upon by someone else to the point where it outlasts the original project.

Sharpe's story about a bunch of friends making up their own religions after college is almost painful in the way it combines absurdity with verisimilitude. He captures that aimless feeling of trying to figure out one's life and purpose after years of regimented education. Channeling it through these absurd religions and later the prism of fame gives the story a focus and a sturdy metaphor for all sorts of post-grad ennui.

Other highlights include a Sharpe story about a man whose sense of their body in space becomes attached to a long-lost crush, and he shrinks when she walks away. It's all played for laughs, but it's another potent metaphor. There's also a sci-fi story about a group of explorers who bring back a cursed object, one that creates mild disappointment in everything. Goodrich employs more of a scribbly, expressive line that also makes starker use of blacks, while Sharpe uses a cartoony/naturalism hybrid, often with anthropomorphic animals. Their aesthetic differences blend nicely, providing a visual palate cleanser for each other's stories.

Other highlights include a Sharpe story about a man whose sense of their body in space becomes attached to a long-lost crush, and he shrinks when she walks away. It's all played for laughs, but it's another potent metaphor. There's also a sci-fi story about a group of explorers who bring back a cursed object, one that creates mild disappointment in everything. Goodrich employs more of a scribbly, expressive line that also makes starker use of blacks, while Sharpe uses a cartoony/naturalism hybrid, often with anthropomorphic animals. Their aesthetic differences blend nicely, providing a visual palate cleanser for each other's stories.

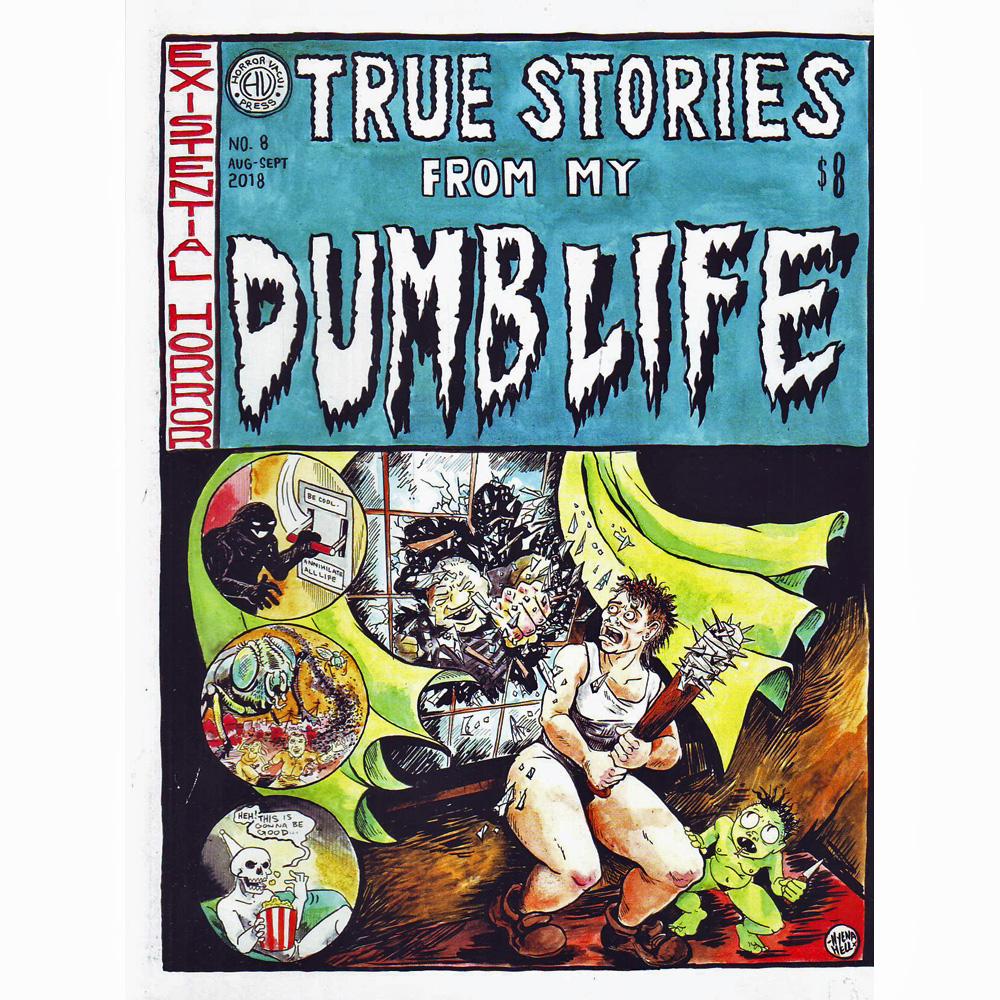

True Stories From My Dumb Life 6-8, by Hyena Hell. (CAKE 2019) The punk rock autobio comic is alive and well, thanks to people like Buck, Hyena Hell, Liz Suburbia and others. Hell talks about her love for old Ghost Rider comics, social anxiety, stress about her job and her art, her love of drawing dicks, and dealing with two avatars: a small, nude imp version of herself that represents her unbridled creativity and a nude, skull-faced version that represents depression, self-doubt, and self-hatred. Hell gets a lot of comedic mileage out of these three characters and their interactions, and one of the best parts is how she draws them. There's a dense, scribbly realism in their appearance, which makes them all the more unsettling. They are real in every important sense, and the solidity of their physical presence is every bit as valid as Hell's own presence.

True Stories From My Dumb Life 6-8, by Hyena Hell. (CAKE 2019) The punk rock autobio comic is alive and well, thanks to people like Buck, Hyena Hell, Liz Suburbia and others. Hell talks about her love for old Ghost Rider comics, social anxiety, stress about her job and her art, her love of drawing dicks, and dealing with two avatars: a small, nude imp version of herself that represents her unbridled creativity and a nude, skull-faced version that represents depression, self-doubt, and self-hatred. Hell gets a lot of comedic mileage out of these three characters and their interactions, and one of the best parts is how she draws them. There's a dense, scribbly realism in their appearance, which makes them all the more unsettling. They are real in every important sense, and the solidity of their physical presence is every bit as valid as Hell's own presence.

Issue #8 is my favorite, as she alternates between her typical style and Guy Gilchrist-inspired Nancy drawings. That cartoony stiffness is a stark contrast to her grainy, inky art, but it's that very contrast that makes them funny. There's a great strip later where her skull-faced tormentor is having a hard time making Hell feel bad; she walks by the usual self-doubt, anxiety, and depression in the form of demonic monsters. So the skull-Hell plays dirty: slapping her with a uterus, which sends her human counterpart spiraling off into despair. It's a smart, funny take on how one's own body and hormones can betray you. Hell has such a strongly defined style and inviting inner monologue that she's able to make every variation on her stories about mental health entertaining.

Issue #8 is my favorite, as she alternates between her typical style and Guy Gilchrist-inspired Nancy drawings. That cartoony stiffness is a stark contrast to her grainy, inky art, but it's that very contrast that makes them funny. There's a great strip later where her skull-faced tormentor is having a hard time making Hell feel bad; she walks by the usual self-doubt, anxiety, and depression in the form of demonic monsters. So the skull-Hell plays dirty: slapping her with a uterus, which sends her human counterpart spiraling off into despair. It's a smart, funny take on how one's own body and hormones can betray you. Hell has such a strongly defined style and inviting inner monologue that she's able to make every variation on her stories about mental health entertaining.

TCCN Comics Anthology 1, edited by Patrick Holt. (Zine Machine 2019) Published by the Durham Public Library, this comic was the result of a call for local contributors. Many of the contributors are first-timers or self-publishers, but the anthology itself is well-designed. Each contributor in this 36-page anthology got two pages, but there's clearly a deep level of commitment on the part of the cartoonists and a keen sense of how to sequence a wide variety of visual and narrative approaches.

TCCN Comics Anthology 1, edited by Patrick Holt. (Zine Machine 2019) Published by the Durham Public Library, this comic was the result of a call for local contributors. Many of the contributors are first-timers or self-publishers, but the anthology itself is well-designed. Each contributor in this 36-page anthology got two pages, but there's clearly a deep level of commitment on the part of the cartoonists and a keen sense of how to sequence a wide variety of visual and narrative approaches.

For example, an artist named meltycat starts the anthology with a scratchily-drawn dream comic about being back in her childhood bed, only it's full of roaches. Elizabeth Kilgore's silent, naturalistically-drawn comic is about waking from an upsetting dream in tears. The next strip is Kelly Stiles' "Sad Seal," taking off from that last image in the previous strip to go to a seal wondering why it's so sad. The drawings range from the manga-inflected work of Claire Bushey to the dense, inky, and grotesque drawings of Marx Myth. My favorite strip was by Julia Gootzeit: a quiet, poetic meditation on an intimate moment when her partner put a band-aid on her. In general, everything about this anthology was well-executed; while many of the cartoonists were previously unpublished, one get a sense that every contributor gave their best effort, and they were rewarded with a format and forum that made their work look good. There was no self-aggrandizement here; the work speaks for itself.