Originally featured in Kinema Junpō (Cinema Monthly) No. 1853, late November, 2020

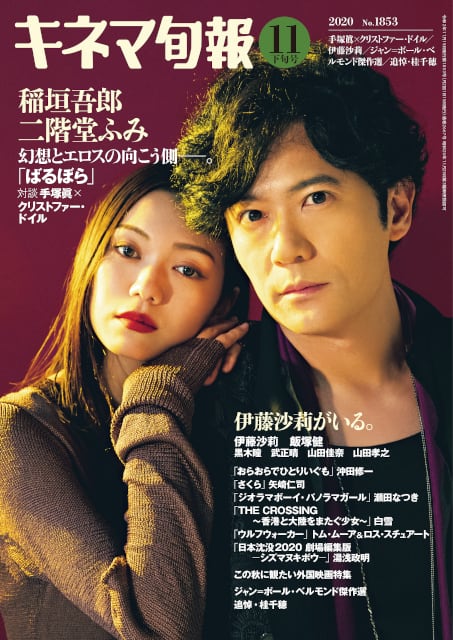

In this article from Japan’s Kinema Junpō magazine from November 20, 2020, Natsume reassesses Tezuka Osamu’s early '70s seinen manga serial Barbara—the story of a creatively parched and sexually-obsessed writer's relationship with a mysterious hippie wastrel who may be a muse—from which a 2019 film version was adapted and directed by Tezuka Macoto, the artist’s son. Featuring the talents of the actress Nikaidō Fumi and Inagaki Gorō (formerly of the boy band SMAP), the film was nominated for a number of awards, including the Grand Prix at the 32nd Tokyo International Film Festival. Natsume reflects on the stunning risks Tezuka Osamu took to make the manga at that point in his career, and how it was a difficult manga to make (and a difficult film to produce for his son). In this short piece, Natsume continues to build on his assessment of Tezuka, which was the focus of his first manga monograph, a classic in manga studies, Where Is Tezuka Osamu? (Tezuka Osamu doko ni iru; Chikuma Shobō, 1992).

-Jon Holt & Teppei Fukuda, translators

* * *

Tezuka in Crisis in the 1970s

Tezuka’s Barbara was a manga all about “eyes”. Why does his male protagonist Mikura always wear sunglasses? It is because it is an act of self-denial, an act to deny “manga eyes”. Why do Barbara’s pupils look like x-marks? It is because Tezuka tried to capture—tried to follow—the “nihilism” of the zeitgeist by copying artists like Nagashima Shinji who started expressing nihilism with blank eyes - and, in doing so, Tezuka was rejecting his own previous style of manga.

After all, it was Tezuka himself who was the person that brought psychologically nuanced expressions to postwar manga by blending eye expressions with psychological codings and their permutations. Furthermore, that kind of approach became a part of the manga system for nearly 20 years, and it is only in the 1970s that the younger generation of artists then tried to transcend Tezuka. Tezuka himself was greatly worried about the new trend; he was jealous of the new artists; and, he beat himself up trying to change his style.

At the time of its publication (1973-74), Tezuka was facing a major crisis. With the arrival of gekiga (dramatic/mature manga), there was a major revolution carried out by fresh, younger artists (Ōtomo Katsuhiro!) who were working in seinen (young men’s) manga. Tezuka became the “old-fashioned” artist, and even manga magazine editors began to treat him that way. I heard that while Tezuka was working on Black Jack, younger magazine editors did not want to be in charge of that manga or the artist. It got worse for Tezuka when his production company, Mushi Pro, went bankrupt in 1973. Tezuka, who always had that kids-manga side to him, started being dismissed from the frontlines of the industry.

In Barbara, Tezuka has dog and mannequin characters become sex objects for the protagonist Mikura in his sick and delusional state. We can even read this as Tezuka’s own self-denial of his semiotic manga expression where he would often put animals and humans living happily together in harmony (Jungle Emperor, anyone?), where any character looked like a doll in their human encodings. Later (in 1977), Tezuka could objectively view his theory of pictures, in that manga = signs, and state that in his How to Draw Manga (Manga no kakikata).

Tezuka’s penchant for having humans and animals live together in harmony is emblematic of the way he relativizes human existence, similar to a boundary between humans and non-humans, where Tezuka’s demons, aliens, artificial beings, robots, etc. often live. In Tezuka’s manga, characters emblematic of that boundary often are full of sexual appeal (or: eros). I think in Barbara, Tezuka, instead of relativizing that boundary between the human and the non-human, attempted to clearly demarcate that eros. This also happens, too, in Ode to Kirihito (Kirihito no sanka, 1970-71), his earlier serialized work for Big Comic that precedes Barbara, in Tezuka’s depictions of the human protagonist’s disease that is making him into a dog shape.

You might ask why he went on to make this a part of theory of his art? Actually, even earlier than in those works, Tezuka was interrogating manga expressions, as seen in his “Phoenix” chapter of his larger Phoenix (Hi no tori) series that was published in his own COM magazine from 1969 to 1970.1 Again, we see in other works before and around Barbara that he was trying to be self-critical in some of his autographical and comedic-touch manga, like Record of the Gotchaboy the First (Gatchaboi ichidai ki, 1970) and Paper Fortress (Kami no toride, 1974).

Barbara as Tezuka’s Artistic Statement

What Tezuka does is pass the question that he posed in “Phoenix” onto the novel (shōsetsu) in Barbara, and then he reshaped it into a larger question of a meaning of art (geijutsu-ron). After all, its protagonist Mikura is a novelist who tries to rationalize as “art” (geijutsu) all those “perversions” (ijōseiyoku) of his and his “delusional mind” (genkaku shōjō), which he defends as being a kind of “decadent” (tanbi-shugi) form of art. I do not fully know how much Tezuka himself was aware of all of this, but I cannot help but feel that once Tezuka took up this subject matter, by necessity, he could only do this topic by forcing himself to examine what his own “expression” (hyōgen) really meant.

The question Tezuka posed in Barbara was whether it was right or wrong for anyone to use their talent or their art to stir up trouble for society with ethical issues. At the same time, this question becomes a chance for Tezuka to interrogate the conflict between oneself and the limitations by both society and one’s zeitgeist, and, whether an artist should be bound by them or transcend them. It might be possible to say that this was Tezuka testing his hypothesis as he tried to understand what happens once a person believes that his self-expression can be art. I wonder if this kind of thinking came from his own experiences earlier in his career when he was harshly criticized by parents and by educators about what he was doing in his manga.

The conflict between art and commercialism still was seen at this time as self-contradictory. Tezuka’s own view on art is still found somewhere in this fight. As a result, a part of his perspective is hard for people in modern days to understand given the context of this issue, so if we keep raising the same old question (the dichotomy of art and commercialism), we will not find our answer. What we soon see instead is that, as the times changed and Japan became a high-consumption society, what were two separate issues—artistic expression and consumption—become two sides of the same coin (culture and commercialism), so that this question itself becomes completely unraveled. What was called sub-culture (sabu-karu) rises into its own form of consumer culture, and it relativized the equation of high art (geijutsu) = “main culture” (mein-karuchaa).

And yet, for Tezuka during this time, you can see he was desperate to remake the system of manga production that he himself put into place - and, he was desperate to free himself from that very system. Think about what Tezuka achieved during this period: on one hand, he accomplished a miraculous comeback as an author of shōnen manga by creating Black Jack (1973-78) and The Three-Eyed One (Mitsume ga tōru, 1974-78). On the other hand, he was also producing during this same time a number of superb works for the seinen manga magazines. In the years leading up to and following the serialization of Barbara, you see other works like Ode to Kirihito, Ayako (1972-73), Shumari (1974-76), MW (1976-78). All of these are masterpieces. A bit later, when we get to A Tree in the Sun (Hidamari no ki, 1981-86), which is based on his real-life ancestor in the Edo Period [1600-1868], I feel that Tezuka accomplished a reconciliation with himself.

A Peculiar Junction in Tezuka’s Manga

Achieving a place in his career where he could draw whatever he wanted—no longer constrained to do children’s manga—gave Tezuka a space to experiment with the look of his manga during this period of crisis for the artist. Mori Haruji, who was head archivist for Tezuka Productions, recorded his impressions of Tezuka in his commentary essay for Barbara: “It may not look like the manga shows any influence from his daily life, but in fact, Tezuka’s pen was peculiarly flowing during that time.”2 Tezuka was freed from the financial operations of Mushi Pro and also liberated from producing anime, so you cannot help but imagine just how much he was able to focus on his manga that let him ask himself what was the meaning of his manga.

Mori also writes: “The proof that Tezuka loved Barbara is how he had it published in trade paperback immediately after its serialization was over.” But Tezuka himself wrote in the book’s afterword, replying to reader responses: “There are a number of parts of the manga that people cannot seem to understand.” He even pleaded his case: “Barbara is not some minor work that I cut corners to make.”3 That seems so like Tezuka, but it might be true that peoples’ reactions did not meet his expectations.

Even so, as a person who read Barbara at the time of its serialization, the work left a strong impression on me. The reason why is that among Tezuka’s works, there are not many that address head-on the issue of artistic expression, so I felt something strangely compelling about it. I have long felt that since it first came out, Barbara is a peculiar junction in Tezuka’s career. It is a manga to which we should give more attention. I’m grateful that this essay has given me a chance to leave a few comments about Barbara from my perspective of my manga expression theory (manga hyōgen-ron).

However, let me make a few comments about the film adaptation of the work directed by his son, Tezuka Macoto. At the end of the film, we suddenly have the scene where Mikura commits a necrophiliac act. No corpse appears in the currently published editions of Barbara, but the original serialized version did have the scene of necrophilia on the snowy mountain.4 I supposed that Tezuka must have been trying to depict a complete escape from morality in Barbara, and you certainly get the feeling in the manga that Tezuka must have thought to himself, “I did it anyway.”

For me personally, as someone who is a fan of [the actress] Nikaidō Fumi, the movie allows me to really enjoy Fumi’s beauty.

* * *

- TRANSLATORS' NOTE: Natsume is referring to the fourth part (“Hō-ō”) of the Phoenix series, published by VIZ in English with the subtitle “Karma”.

- Mori, “Kaisetsu”, Tezuka Osamu Bunko [Pocket-sized] Collected Works: Barbara (Kōdansha, 2011).

- Tezuka, “Atogaki”, Barbara (Vol. 2 in The Complete Manga Works of Tezuka Osamu [Kōdansha, 1982]).

- Please see the 2019 edition published by Shōgakukan Creative, Barubora Orijanaru-ban, episode 12 (“Extreme Interrogation”). The Daitosha version (published in 1974), which is now the version commonly seen in print, is the edition where the scene started to be cut from the manga.