“I consider this a very important part of my career,” Eisner told me when we talked in 1998, “because as you know I’ve always believed that this medium–sequential art–is capable of dealing with subject matter far more broad, far deeper, than the simple stories we have today. But I’ve also felt that this was a truly great instructional tool. I learned of its value in the military, actually, when I was in the Army in World War II. Then I had a chance to spread my wings on something that I firmly believed in–religiously.”

R.C Harvey, “An Affectionate Appreciation”. The Comics Journal #267 (April/May, 2005), pp. 80-81.

June 2021 marked the 70th anniversary of PS, The Preventive Maintenance Monthly—or, PS Magazine—which remains a testament to Will Eisner’s genius and the U.S. Army’s penchant for instructional-design strategies. Eisner’s contract lasted from 1950 until October 1971, and produced 227 issues with a myriad of memorable characters. Those who took the reins after Eisner included former assistants and acolytes Mike Ploog, Murphy Anderson, and Joe Kubert, all of whom provided artistic consistency and excellence. But Eisner created something that endured well beyond him, thanks to an incredibly dedicated internal staff of managing editors and staffers such as Paul Fitzgerald, who withstood friendly fire from within the military and the bevy of outside civilian criticisms. Sadly, Army leadership directed the end of the periodical comics publication in 2019, making November of that year its last 64-page, cartoon-illustrated issue; thus ended the longest-running series of an instructional comic book, forcing PS Magazine to evolve into an online-only information portal, where Eisner characters MSG Half-Mast, Connie Rodd and others have been made quasi-alive through the repurposing of older graphics. PS’ purpose, however, has never wavered: to instruct soldiers on the repair, storage, use, maintenance, and ordering of the “world’s best equipment.”

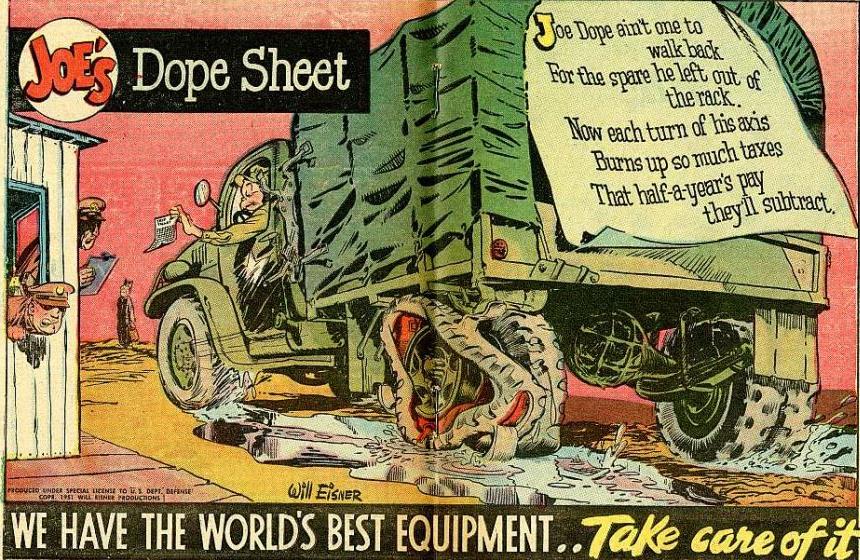

Eisner’s and the Army’s eventual marriage through instructional comics began after Eisner was drafted in 1942, already a successful cartoonist, and stationed at Aberdeen Proving Ground outside Baltimore. There he was approached by the editors of the camp newspaper, who were looking for a cartoonist, and he soon became editor of Firepower, an ordnance journal and maintenance manual. Eisner was next involved in the creation of Army Motors, for which he developed the lovable klutz, Joe Dope. Eisner’s cartoons did a better job of getting the message out than the straight text of manuals. His characters pulled the reader in, and the combination of image and words minimized complicated descriptions. Eisner’s comics could be read by all reading-level types, and soon enough, his cartoons and strips were included in various other manuals.

These successes, and the impact of the Korean War, led to the birth of PS Magazine. The equipment used during the Korean War was described as either too old or too new—scraps from the recent dispersion of mass equipment from the end World War II intermingled with rushed and barely tested products. The quagmire of equipment was deemed a logistics issue, and Ordnance Corps was ordered to revive Army Motors based on its popularity with soldiers and focus on communication. The 1950 Memo establishing PS shows Colonel F.G. Crabb, Jr. establishing a Preventive Maintenance Agency at Aberdeen Proving Ground, with a network of civilian technical advisors overseen by James Bell. Norman E. Colton, a former staffer on Army Motors, was the first Army editor of the magazine, and Eisner was the first civilian contracted to provide creative art, publication design, and all pre-press production materials. With an initial trial authorization for six issues, the first issue appeared in June of 1951. Response was enthusiastic and a twelve-issue extension was immediately granted. Soon, however, the honeymoon would end.

Because of PS’ invitation for reader feedback, editors soon discovered not many colleagues in the Ordnance Corps appreciated hearing how their designs and features were failing or struggling. In an effort to kill the messenger, in January of 1955, PS Magazine was moved from Aberdeen Proving Ground to Raritan Arsenal under the benevolent gaze of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Daly.

Daly was highly concerned about internal complaints that PS Magazine characters were offensive to the dignity of the American soldier. Some PS staffers at this time described recurring harassment by field-grade officers in the name of pride and dignity. These officers and amateur comics critics were convinced that goofballs such as Joe Dope and Private Fosgnoff were insults to the uniform and those who took pride in their appearance. In June 1955, the gossip of resentment reached the top, and then-editor Jim Kidd and managing editor Paul Fitzgerald were summoned to the Pentagon. In preparation for that meeting, the editing team assembled a dense package of testimonials, memos, and a study, Humor and the American Soldier, which suggested that any misunderstanding of PS humor was from misunderstanding the American soldier and his vernacular. The study was heavily footnoted and included attached exhibits such as the training manuals for Caterpillar farm machines as further examples of using humor and practical realism to instruct. Unfortunately, the status quo prevailed, and the cast of PS characters was diminished. Private Fosgnoff was summarily dishonorably discharged and Joe Dope was allowed a reprieve that only lasted until 1957.

Corny criticisms aside, it’s true that the culture of the Army was slow to reflect the changing gender dynamics of the rest of the nation. The use of the Connie Rodd character as cheese cake for readers’ enticement became an irritating and problematic matter, despite an enthusiastic beginning. An article in the New Brunswick, New Jersey, Sunday Times in 1955 happily points out that Connie can just as breezily install a gun mount as dismiss a sexist soldier. Yet as the composition of the Army began to change under the growing number of women in occupational specialties, public sentiment had shifted radically, and a 1972 article in the San Francisco Chronicle took issue with Connie’s appearance in an M16 manual. The article interviewed soldiers who admitted to being lustful young men, and coupled them with concerns of political action groups such as the Military Law Project, who objected that the cartoon depictions of women would have a negative effect on impressionable young soldiers. The public criticism began a slow simmer that boiled over in 1980. Then-New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug and Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire called a Congressional budget hearing for PS that resulted in the first of severe staffing and production cost cuts for the magazine.

In the Army’s own retelling of the beginnings of PS Magazine, first in the 1964 edition of Army Information Digest and then later in the 65th anniversary issue of PS Monthly (June 2016), neither Eisner nor his artistic successors were explicitly mentioned, despite their work, characters, and tropes being used throughout. Instead, the Army focused on the logistics problems that PS was designed to address and how they accomplished the communications mission of saving equipment and lives. We were, of course, given the explanation that the title letters “PS” refer to the “post script” function of the comic book, because PS contains updated information not found in the traditional Army technical manuals. In the ’64 telling of the birth of PS, Eisner contributes a small strip to explain to readers, pre-dating Scott McCloud’s self-reflexive exercises, how the magazine functions with reader support.

By the time of the 1980s’ dark days for PS, Eisner had long left the many internal battles with top brass that were needed to keep PS going. Eisner was always proud of the troops’ reaction to his work, rather than the officers and administrators. He was allowed field trips and granted access to bases and camps as background research for the publication, and Eisner took full advantage of this privilege beginning with the Korean War until the Vietnam War, with one of those later junkets becoming the basis for his graphic novel, Last Day in Vietnam. One can see Eisner’s full artistic legacy on brilliant display in the his entire run of the magazine, archived online at Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries Digital Collections, but there's also enough Eisenshpritz in action to keep the tactile-inclined reader engaged through the lovingly reproduced, 250-odd pages of the 2011 Abrams collection. Sadly, much of Eisner’s and others’ original art were burned in a document destruction furnace during the move to Redstone Arsenal in Alabama in 1993.

After Eisner relinquished his art and pre-press production contract with PS Magazine in ’72, Mike Ploog took over. He had already been a key artist in the PS Magazine universe for seven years, after being principal artist in Will Eisner’s American Visuals shop. When Eisner ended his contract, Ploog joined Bob Sprinsky, Chuck Kramer, Dan Zolnerowich, Murphy Anderson, and Ted Cabarga to form Graphic Spectrum Systems in a successful bid. To ensure continuity, they worked with Eisner on PS Issue 227 before doing PS 228 completely without him. The group only survived a portion of the single two-year contract. Ploog explained his short time on PS to interviewer Dirk Deppey in The Comics Journal #267: “Well, I wasn’t making any money and the schedule was a nightmare. I felt that I really couldn’t handle the project, not under the circumstances that I had it.” On the PS production side, there was an anger about the lack of an organizational hierarchy within Graphic Spectrum Systems, resulting in PS 251 (October, 1973) being the last issue.

Murphy Anderson was another key artist in Will Eisner’s shop, also doing work on PS as part of the American Visuals crew. Anderson won the PS contract in his own right in November of 1973, doing business as Visual Concepts. His crew consisted of Frank Chiaramonte, Augie Scotto, Dan Zolnerowich, Creig Flessel, Craig Daniels and Howard Berman. Joined by Murphy’s son, Murphy Anderson III, his wife, Helen Murphy, and his daughter, Sophie Murphy, they produced PS 252-368. There is a six-month exception (August ’78-January ’79) when lower bidder Zeke Zekeley and his Sponsored Comics won the PS contract and produced PS 309-314 before defaulting on the contract. Zekeley’s staff included Terry Bratcher as production manager, Dan Spiegle doing continuities, and Alfredo Alcala handling covers and two-color pages.

Backes Graphics, a firm in Princeton, NJ, owned by Diane and Jack Backes, held the art contract for twelve years, from July of 1988 through January of 2001, producing PS 428 through PS 578, second only to Eisner’s twenty years of creativity at the beginning of the publication’s seventy years of services. The person who had probably written and drawn the most PS stories as lead artist was Scott Madsen, whose previous experience with comics came from the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art.

Neal Adams relates, in Bob Andelman’s Will Eisner: A Spirited Life, that he and his Continuity Studios were approached about bidding on the PS Magazine art contract. Adams wrote that he wasn’t interested, but instead reached out to Eisner and floated the idea that the combination of Kubert and the renewable resource represented by his student body would be ideal for the PS challenge. Kubert competed in the bidding in late 2000 and won the PS art contact beginning with issue 579 in February 2001, renewed in 2007 and 2016. Also in 2016, the original logo, with its rounded serif PS letters within a circle, was redesigned to feature shortened, widened, and angular letters overlapping a circle. Despite the slew of changes to PS and its characters, the longstanding constant element of PS is its commitment to the readers and subscribers and providing life-saving information that would reach as many readers as possible.

During the end of its print run, the Army’s Logistics Support Activity (LOGSA) distributed approximately 32,000 copies monthly, a dramatic drop from a peak of almost 190,000 copies printed monthly in 1989. As an online information portal and brand, PS has had greater availability through website, blog, and social media presences, as well as being a mobile phone application for iPhone and Android users. The website and mobile phone application include digital PS issues. Believe it or not, accessing PS Magazine until recent years had mostly been restricted to U.S. military personnel or visitors to Federal Depository Libraries. PS has now been made accessible to the public in an online environment through various archives, and interest in PS among comics scholars, educators and historians has grown. It’s imperative that PS be viewed as a unique collection of genres with a function beyond providing technical instruction. The genres—illustrated letters to the editor, procedures, questions and answers, as well as an eight-page non-technical graphic narrative usually featuring one or more of PS’ recurring characters—are presented in one publication. Though other branches of U.S. military service have produced comics, PS will probably remain the only U.S. military instructional comic book.