T odd McFarlane was fantastically successful for a brief span of the 1990s, successful enough that he was able to parlay a brief dalliance with the zeitgeist into a lifetime’s worth of cred in a very narrow field. He defined an aesthetic for a broad swathe of the country composed of a mass of bituminous Hot Topic signifiers that coalesced into Spawn. McFarlane learned that the segment of the population who thinks that Pantera are better than Metallica is the most loyal audience on the planet. Draw demon clowns from hell with guns wearing JNCOs listening to proto-rap-rock while skateboarding. How do you do, fellow kids?

odd McFarlane was fantastically successful for a brief span of the 1990s, successful enough that he was able to parlay a brief dalliance with the zeitgeist into a lifetime’s worth of cred in a very narrow field. He defined an aesthetic for a broad swathe of the country composed of a mass of bituminous Hot Topic signifiers that coalesced into Spawn. McFarlane learned that the segment of the population who thinks that Pantera are better than Metallica is the most loyal audience on the planet. Draw demon clowns from hell with guns wearing JNCOs listening to proto-rap-rock while skateboarding. How do you do, fellow kids?

The problem with McFarlane is that while he was able to conjure up a sizeable fanbase based on his art and his design sense, he was never a storyteller. Spawn remains all premise and no saga. I don’t care to speculate about McFarlane’s personal motivations as a creator. But as a businessman and someone who spent a solid decade as the most outspoken man in comics he lacked even a shred of a salesman’s warmth. He loves sports and money and oddly doesn’t appear to have much of an imagination. Beyond that, it might as well be Just Imagine . . . Stan Lee’s Bret Easton Ellis.

Mark Millar deserves similar credit for seeing an emerging demographic as it was beginning to form. Unlike in McFarlane’s case, this was not an aesthetic revelation but one solely of attitude. Millar saw not just that the culture was becoming increasingly crass – no great sin in and of itself, certainly – but that one of the growing engines of this crassness was an emerging generation of teen and twenty-somethings who grew up listening to Eminem and watching South Park. I did these too but I outgrow both of them around the same time. A lot of other people didn’t, or at least didn’t outgrow the idea that it possible to regain symbolic power across culture by transgressing boundaries of “PC” politesse that had never really solidified in the first place and were still often observed more in the breach.

People were getting angry and they were getting angry because they understood perhaps on some level that the twenty-first century we all got was not the twenty-first century for which we had hoped. Look at Millar’s signature creator owned books – Kingsman, with Dave Gibbons, Wanted, with J. G. Jones, and the franchise we’re discussing today, Kick-Ass with John Romita Jr. They’re all stories about white boys without a lot of social or economic pull who figure out how to somehow improve themselves through mastering the art of ultraviolent retribution.

Superhero stories are customarily regarded as power fantasies. They certainly are, and of the most basic kind: I can’t fly or bend steel with my hands, but Superman can and sometimes he even does interesting things with those abilities. Millar’s resentful manchildren graduate to super-status without ever learning the most basic Peter Parker lesson about responsibility. Their very limited power is only useful if it can be fueled by the kind of resentment that is customarily purged from the spandex fraternity at the point of entry. Millar’s great contribution to superhero comics was not in realizing that superheroes could be shitty people but that the audience could be shitty, too. There was a market for stories where people just didn’t give a shit and people who got kicked in the face just learned to kick back harder and with better quips. These aren’t power fantasies for children, they’re the fantasies of powerless young adults.

Well, there's a new Kick-Ass in town and she’s named Patience. She puts on the Kick-Ass costume not out of sincere tribute but to frame mugging some drug dealers as hero worship and not a cash-strapped veteran going Omar Little on Albuquerqu. Patience is back from the war in Afghanistan to find her husband having skipped town with the new girl at the office. She had been planning on going back to school, now she had to get a job. Finding her earning potential significantly diminished after returning from the war she hits on the idea of using her combat training to make some easy money.

Well, there's a new Kick-Ass in town and she’s named Patience. She puts on the Kick-Ass costume not out of sincere tribute but to frame mugging some drug dealers as hero worship and not a cash-strapped veteran going Omar Little on Albuquerqu. Patience is back from the war in Afghanistan to find her husband having skipped town with the new girl at the office. She had been planning on going back to school, now she had to get a job. Finding her earning potential significantly diminished after returning from the war she hits on the idea of using her combat training to make some easy money.

You can imagine the complications. She’s discovered. She gets knocked around a bit but mostly just waits until she’s certain they’ve completely underestimated her before mopping the floor with a roomful of desert wiseguys. All very orderly business.

There’s an extended flashback sequence in Afghanistan where we see Patience as an effective and professional soldier in what appears to be a Special Forces unit of some kind doing soldier-y stuff against a backdrop of central casting terrorists. The first Kick-Ass got his ass kicked a lot, that was basically the character’s only real super-power. He could survive taking a punch, which is a respectable skill for any tough guy to have. The new one doesn’t appear to really need to take a beating, since she actually knows how to fight.

I’ve always regarded the first Kick-Ass as an important book if not a very significant one, if that distinction makes sense outside my head. It seemed to want to be a more significant book than it actually was, though it didn’t really have a lot to say for itself. It sold a lot of comics and seemed to have some legs – Maybe not as many as Millar might like, as the second movie ended the franchise – but it’s an essentially mean-spirited IP and the property is better suited to a midnight movie format than as an actual real franchise. The movie sanded down a few of the book’s more contemptible episodes of misanthropy and misogyny and frankly did a better of of presenting the material than the material may have deserved.

Now we’re here with a new Kick-Ass, and in the tried-and-true legacy hero tradition it’s a woman of color. And it’s no longer about high school age (and younger!) kids trash-talking each other as they hack each other to bits with chainsaws or what not. It’s about underemployment and the gaps of the “gig” economy and the fact that soldiers go overseas for years to do things for reasons no one at home really understands or even, in 2018, cares about. These are big ideas, real things to build a story around. But even though this story is still only one issue old, I don’t know if this is a story that’s going to do justice to that premise. Because it’s still a story about someone putting on an ugly green jumper and calling themselves Kick-Ass, and I just don’t know if Kick-Ass is a concept that can bear any dramatic weight whatsoever. It’s completely insubstantial.

The best thing about Kick-Ass is still, as it’s always been, co-creator John Romita, Jr., who certainly can’t be accused of phoning anything in despite the general distastefulness of the material. I give Millar slack because as schlocky and exploitive as some of his comics can be, Romita deserves every cent. He deserves it because he has to draw an exploitation movie pitch with a frankly reactionary attitude towards the redemptive power of violence as a channel for the human spirit . . . same deal with Dave Gibbons and the equally indefensible Kingsman franchise. Gibbons should co-own Watchmen, so he can make money off some spy trifle.

The best thing about Kick-Ass is still, as it’s always been, co-creator John Romita, Jr., who certainly can’t be accused of phoning anything in despite the general distastefulness of the material. I give Millar slack because as schlocky and exploitive as some of his comics can be, Romita deserves every cent. He deserves it because he has to draw an exploitation movie pitch with a frankly reactionary attitude towards the redemptive power of violence as a channel for the human spirit . . . same deal with Dave Gibbons and the equally indefensible Kingsman franchise. Gibbons should co-own Watchmen, so he can make money off some spy trifle.

Millar is good at setting excellent artists up with remunerative gigs, and that’s nothing to sneeze at even if the results of much of his work – at least his creator-owned work – are mean-spirited and sour. He’s not incapable of good work. He’s seems comfortable working sometimes with a lighter touch – when he has to tone down the shock effects he can actually produce interesting work. His work-for-hire stuff is oddly much more interesting to me than any creator-owned work he’s ever done. His creator-owned work is remarkable in its impersonality, and frankly, left to his own devices he’s incapable of moderating his worst impulses. But sometimes with an editor and a character he likes he can do uncharacteristically good work. His Fantastic Four was essentially curtailed by low sales that forced the creators off the book – which is a shame, because the book improved a great deal after the first arc landed with a thud. Many still swear by his run on Superman Adventures. And I remain quite sincerely fond of his Swamp Thing.

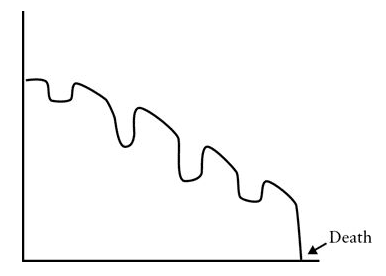

But Kick-Ass – perhaps it’s just not worth the trouble. I don’t think the book has really any more value than Spawn, another book that married a particularly brand of ultraviolent and gory content to the aestheticized rebellion of a specific generation of disaffected and beaten teenagers. Like Spawn before it, it’s greatest value as a creation was to briefly offer an (unintentionally) unflattering mirror to a terribly loyal audience. But just ask Todd: once your demographic ages out of spending all their time (and, more to the point, their money) trying to look or act cool and rebellious, you’re just biding your time until it’s time for the revival.

Which is, I suppose, exactly what this iteration of Kick-Ass is: the timely anniversary-year revival. But regardless of whether or not the title character is a high schooler or a thirty-something vet, it’s a juvenile concept. Bolting topicality onto a struggling juvenile concept never elevates the juvenile concepts as well as creators always seem to think. It just accentuates all the ways the concept may not have aged as well as you might have hoped.