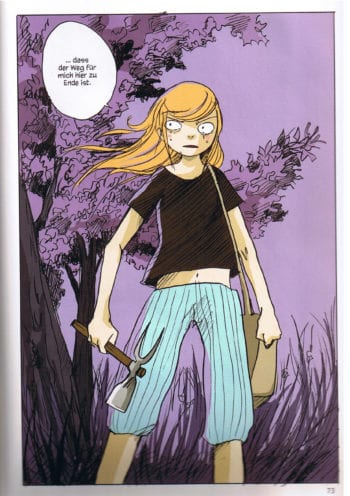

Olivia Vieweg’s first book-length comic, Endzeit, introduces an in-between character in an in-between place. Calling herself “the Gardener,” this character is half zombie, half human. She lives off the land in the German countryside in-between Jena and Weimar, the last two cities not yet overrun by zombies, possibly in all the world. The Gardener’s encounter with Vivi and Eva, the book’s protagonists, who are stranded in this no man’s land, is brief. She delivers them from an undead pursuer, introduces herself as a scientist, and provides clues that may or may not be connected to the origin of the outbreak. The heroines find themselves at a crossroads: Vivi will move on and fight, Eva will remain behind forever. Gleefully accepting her imminent rebirth as a zombie, Eva asks her friend to take one last picture of her. “The expulsion from paradise,” the doomed young woman says, posing dramatically, taking a bite out of an apple as her mortal flesh begins to decay.

This version of Endzeit, which clocks in at 72 pages and doubled as Vieweg’s diploma project at Weimar’s Bauhaus University, was published by small-press comics outlet Schwarzer Turm in 2012. In March 2018, a new edition of Endzeit came out from major German publisher Carlsen: a 282-page book completely redrawn by Vieweg and based on her screenplay for an eponymous film that’s currently in post-production and slated for a theatrical release in Germany in 2019. (Vieweg has been serializing an English translation of the new Endzeit on the Web.) In many ways, Vieweg’s career has come full circle.

Even as a child, Vieweg (the pronunciation is “fee-vague”) felt the urge to tell stories. She assembled her own books with paper and glue, then wrote and drew in them. One was the story of a street cat that found a genie in an old fish can and was granted three wishes.

“I was maybe seven or eight years old when I did that,” Vieweg says. “When I was 11, I was planning to create characters for Disney. I didn’t know back then that character design was a real job. I just thought it would be cool to come up with characters, and I’d gladly leave the rest to other people.”

“I was maybe seven or eight years old when I did that,” Vieweg says. “When I was 11, I was planning to create characters for Disney. I didn’t know back then that character design was a real job. I just thought it would be cool to come up with characters, and I’d gladly leave the rest to other people.”

As a teenager in Jena, a university town with a population of 110,000 in the German state of Thuringia, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Vieweg says she didn’t know many other people who shared her interest in Japanese comics and animation.

“Without the Internet,” she says, “I’m certain I wouldn’t have been able to make contact with other fans of manga and anime.” The manga that influenced her the most growing up, Vieweg says, was Sailor Moon.

“It was like a Big Bang,” she says. “Almost all the comics were made for men. And all those Disney shows I loved at the time also had male heroes, and they stuck to self-contained episodes. Sailor Moon had an all-girl cast and longer story arcs, the heroines grew older, they had relationships and remembered them in subsequent episodes, wow! When Uncle Scrooge fell in love, the collective memory of Duckburg would always be wiped at the end of the story. Even now, when I re-watch the Sailor Moon anime with some distance, I get excited by the show’s great sense of humor and self-deprecation.” After discovering Sailor Moon, Vieweg started reading a whole range of manga titles reprinted in Germany.

“I wasn’t picky,” she says. “It was great that they went on to publish books like Naoki Urasawa’s Monster, as well. His exceptional art and incredibly cinematic storytelling did much to impress me.” Another favorite Vieweg mentions is Mohiro Kitoh’s Naru Taru, published in the United States as Shadow Star.

“I read the first volume during summer break,” Vieweg says, “at a time when I thought I already knew all the stories. And then I saw this manga with its somewhat awkward art and a story that seemed very harmless at first but grew so twisted eventually that the art had to be changed in later volumes [of the German reprints]. I practically inhaled this manga, and it’s been a strong influence on the way I draw and tell stories.”

Vieweg says it was her discovery of manga that made her want to tell epic stories rather than shorter gag strips. Once she went to study design in neighboring Weimar, Vieweg met other creative people.

“Most of them weren’t comics fans, however, but liked classical children’s-books illustrations,” she says. “Still, I connected with a handful of comics people, and we still frequently get together to draw and work on our projects.”

Vieweg started leaving an impression on the original-German-language manga, or “Germanga,” scene in the mid-2000s, as a contributor to anthology titles like Animexx Manga-Mixx, Paper Theatre, and Es war keinmal, which collect dōjinshi by aspiring German mangaka. In 2009, Vieweg launched a series of cartoon books featuring a character that came to be known as Dicke Katze (“Big Cat”). By 2010, she was an award-winning editor and had curated anthologies such as Subway to Sally Storybook, with manga adaptations of the songs of Subway to Sally, a medieval-styled folk-rock group. Vieweg says she still feels at home with the German manga scene she started out in.

Vieweg started leaving an impression on the original-German-language manga, or “Germanga,” scene in the mid-2000s, as a contributor to anthology titles like Animexx Manga-Mixx, Paper Theatre, and Es war keinmal, which collect dōjinshi by aspiring German mangaka. In 2009, Vieweg launched a series of cartoon books featuring a character that came to be known as Dicke Katze (“Big Cat”). By 2010, she was an award-winning editor and had curated anthologies such as Subway to Sally Storybook, with manga adaptations of the songs of Subway to Sally, a medieval-styled folk-rock group. Vieweg says she still feels at home with the German manga scene she started out in.

“I go to manga conventions frequently, and I like the mood there very much,” she says. “There are many cosplay outfits I don’t recognize nowadays, and I don’t care at all about most current anime and manga, but in part that’s just because I don’t have as much time anymore to read and watch everything.” Though the German comics and manga scenes remain largely separate from each other, Vieweg sees some signs of interaction.

“Quite a few impulses come from manga people, especially,” she says. “Manga fans are younger than comics fans, on average, and more open to doing things differently. But in comics there are lots of people who have long been looking beyond their own backyard, as well. I’m always amazed to see how many older gentlemen come to my signings who know my work and think it’s great. A few years back, a 70-year-old lady showed up and very confidently bought a copy of my zombie comic.”

The only original German-language comics she was aware of growing up, Vieweg says, were collections of the long-running Mosaik magazine, launched in East Germany in 1955, which her dad gave to her.

“But those comics weren’t fun,” she says. “Maybe it was because I mostly had older volumes, which had captions only rather than speech bubbles. I always find that exhausting.” East German officials were opposed to speech bubbles back in the day because they were deemed “too American,” and therefore evil, Vieweg says.

Since graduating from Bauhaus University in 2011, Vieweg has illustrated a range of children’s and textbooks, as well as a nonfiction book on the philosophy of Star Trek written by her father, Klaus Vieweg, a tenured professor. She has self-published a serial magical-girl novel and written and illustrated a young-adult novel, and created her own line of merchandise based on her Dicke Katze character. In 2014 and 2015, she drew a Sunday strip for Berlin newspaper Der Tagesspiegel, titled “Augenfutter” (“Eye Chow”). The comics share of her workload varies greatly year to year, Vieweg says.

“Sometimes I do several children’s books in a row, sometimes I work on my comics for the better part of a year,” she says. “2017 was that kind of year, there was very little room for anything else other than [the new edition of] Endzeit.” In terms of income, she says, comics makes up 40 percent at most.

“Sometimes I do several children’s books in a row, sometimes I work on my comics for the better part of a year,” she says. “2017 was that kind of year, there was very little room for anything else other than [the new edition of] Endzeit.” In terms of income, she says, comics makes up 40 percent at most.

“It just doesn’t pay very well, because print runs are so low in Germany. You have to be lucky and have a best-seller in order for it to be viable.” Under the circumstances, Vieweg doesn’t think it’s possible to plan for a career making comics, she says, because an industry for the mass production of original German-language comics doesn’t exist.

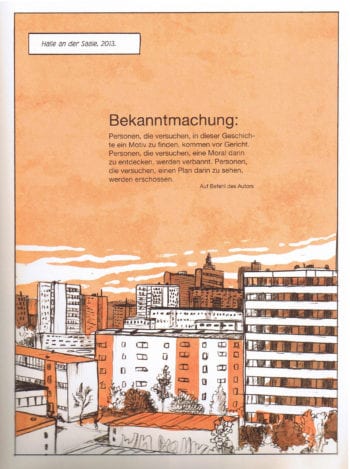

In 2013, Vieweg’s second full-length comic, Huck Finn, along with books by Volker Reiche, Nicolas Mahler, and Ulli Lust, was part of esteemed literary publisher Suhrkamp’s inaugural graphic-novel line-up. A loose adaptation of the Mark Twain novel, Vieweg’s Huck Finn is a shaggy-dog story set in Halle on Saale, an industrial town in former East Germany hit hard by a lackluster post-reunification economy. It stars Finn, a truant with an abusive father, and Jin, a teenage girl forced into prostitution.

With her next book-length comics story, Antoinette kehrt zurück (“Antoinette Returns”), released in 2014 by major publisher Egmont after winning a pitching contest, Vieweg delivered a grim revenge drama set in a small town in Germany’s Harz Mountains, dealing with the cruelty and traumatic repercussions of high-school bullying.

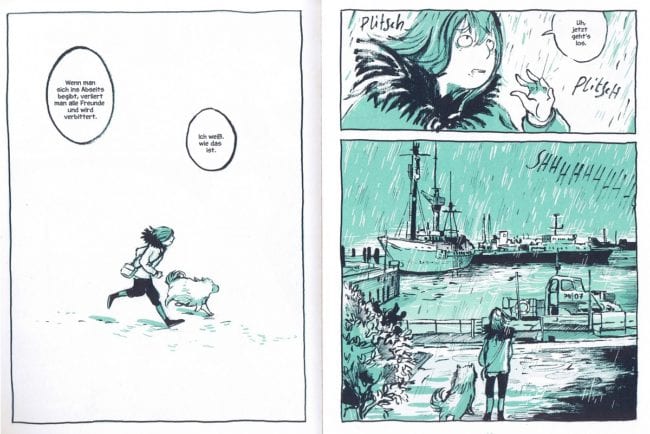

In 2015, Vieweg was back at Suhrkamp with Schwere See, mein Herz (“Heavy Sea, My Heart”), the coming-of-age story of yet another teenage outsider, Heidi, who has developed a crush on the captain of a fishing boat in the North Sea town of Cuxhaven.

Vieweg’s comics are melodramatic and ripe with symbolism, and they make no apologies for it. The situations her characters find themselves in are frequently awkward and grotesque. Vieweg takes narrative risks, and she revels in morbid imagery and body horror. There is a raw, fearless physicality to her work that sets it apart in German comics. While publishers have wanted her to tone things down at times, Vieweg says she’s mostly had the freedom to do whatever she wanted in her stories.

“The fact that my Huck Finn smokes was an issue,” she says. “And that my Antoinette takes revenge without being punished, as well. But I work in children’s books, too, where any earthworm peeking out of the ground might be deemed a phallic object in need of removal. And the kids always need to be smiling on the cover. So I’m glad not everything ends up being second-guessed in my comics.”

There is often a sense that Vieweg’s stories end up saying something important precisely because they’re not hellbent on having to say anything important. Unusually for German popular culture, they leave room for spontaneity, ambiguity, and uncertainty.

There is often a sense that Vieweg’s stories end up saying something important precisely because they’re not hellbent on having to say anything important. Unusually for German popular culture, they leave room for spontaneity, ambiguity, and uncertainty.

Vieweg’s narratives deal with teenage outsiders facing existential threats, threats to the body and to the mind. The zombies seem like one of the more harmless elements in the context of her œuvre, in fact, because their fantastic nature at least affords a degree of escapism. But Vieweg doesn’t want her work to be educational.

“I don’t feel like lecturing people on some issue,” she says. “I will leave that to others. First and foremost, I want my stories to be fun to read.” Unlike most original German-language comics, Vieweg’s narratives aren’t set in some of the country’s bigger cities or in places that are entirely anonymous, but in Jena, Weimar, Cuxhaven, and Halle on Saale.

“I pick settings to communicate a certain mood,” she says. “Halle on Saale has these huge Plattenbau projects where 100,000 people used to live—as many as the entire population of my hometown of Jena. That left an impression on me. On my research trips I got to know both of the town’s faces: There’s the historical old town and the beautiful environment, and then there’s the urban decay. A big adventure playground for a 13-year-old Huck Finn. An anonymous place was never an option. I’d have loved for the story to be set on the Mississippi, but who would have paid for my research trip?”

Stylistically, the manga and anime influences in Vieweg’s work are plain to see, but she refuses to be limited in her approach, or in her themes. Vieweg straddles the borders between the fiefdoms of a fractured German comics landscape with ease, as she does the vast ideological divide between entertainment (U-Kultur) and serious art (E-Kultur) that continues to shape and define the culture industries in Germany. Incidentally, Vieweg’s publishers haven’t always appreciated her Asian influences.

Stylistically, the manga and anime influences in Vieweg’s work are plain to see, but she refuses to be limited in her approach, or in her themes. Vieweg straddles the borders between the fiefdoms of a fractured German comics landscape with ease, as she does the vast ideological divide between entertainment (U-Kultur) and serious art (E-Kultur) that continues to shape and define the culture industries in Germany. Incidentally, Vieweg’s publishers haven’t always appreciated her Asian influences.

“Nobody wanted to print the diploma version of Endzeit,” she says. “One publisher said it was a great story but not a good fit for them stylistically. And at Suhrkamp there was a brief crisis with Huck Finn at one point, when other editors saw my work and didn’t know what to do with it at all. But ultimately all went well and I’m sure they were happy with the book, because they ended up selling the license for two foreign-language markets.”

From the original Endzeit through Huck Finn, Antoinette and Schwere See, the surface features of Vieweg’s manga and anime influences seemed to grow slightly less pronounced with each new book, whereas the new remake of Endzeit brings them back in full force. A deliberate change in direction? Vieweg isn’t sure she agrees with the observation.

“I didn’t really notice, to be honest,” she says. “Maybe the noses in the new Endzeit are a bit more manga-like. But anyway, I’m a huge fan of the manga aesthetic, and it’s not like I want to hide it. I can use some change in style, too, because for a 280-page comic I’ve got to draw faces in about 1,500 panels, so it’s nice when they look a little bit different.” When it came to drawing Schwere See, mein Herz, Vieweg switched from pencils to inks. She says the inspiration came from Jillian and Mariko Tamaki’s This One Summer.

“The ink lines in that book looked great,” Vieweg says. “Also, Schwere See is special, because it’s set in a cold, wet place, which I usually don’t do. My other stories are set in summer and are yellow and orange or completely multicolored. So this was the right book to go and try something new.” Color is a significant storytelling instrument in Vieweg’s work, often serving as a counterpoint to the action. Antoinette, a story about cold-blooded revenge, looks bright and sunny; and Endzeit, particularly in its new incarnation, contrasts the human decay of the zombie apocalypse with a countryside in full bloom. In Huck Finn, Vieweg tapped colorist Ines Korth to help her out. In the new Endzeit, the two are joined by Adrian vom Baur. Vieweg says she needed the help in order to make deadline.

“The ink lines in that book looked great,” Vieweg says. “Also, Schwere See is special, because it’s set in a cold, wet place, which I usually don’t do. My other stories are set in summer and are yellow and orange or completely multicolored. So this was the right book to go and try something new.” Color is a significant storytelling instrument in Vieweg’s work, often serving as a counterpoint to the action. Antoinette, a story about cold-blooded revenge, looks bright and sunny; and Endzeit, particularly in its new incarnation, contrasts the human decay of the zombie apocalypse with a countryside in full bloom. In Huck Finn, Vieweg tapped colorist Ines Korth to help her out. In the new Endzeit, the two are joined by Adrian vom Baur. Vieweg says she needed the help in order to make deadline.

“I drew Huck Finn all through pregnancy and finished it when our son was two months old,” she says. “With Endzeit, I had to take care of our little daughter and couldn’t manage a full workload while there was no available spot for her in day care. Luckily, Ines and Adrian are both very good cartoonists with a good sense of color.”

In the back of the recent edition of Endzeit, Vieweg notes it’s still very hard in Germany to reconcile raising children with having a job.

“In order to be creative, I always need a little downtime,” she says. “There can’t be something going on all the time. Sometimes I need to be able to gaze into space, even if it’s just for half an hour a day, that’s often enough for me. But with two children and the job, I find it hard to make room for that. People tell me about the shows they’ve been watching, what movies they’ve seen, which books they read. These kinds of experiences are important to me, too, but I have very little time for that sort of thing. And as a freelancer, you keep working even when you’re sick, which is not good. But I don’t want to grouse. Just saying, it’s hard if you want to have a job and look after your kids. I can’t just stop working for two, three years at a time and then come back, that’s not how it works.” But Vieweg says the way she chooses or approaches her projects hasn’t changed since she’s been a mother.

“Very little has changed, actually,” she says, “it’s just that everything requires way more planning.”

Vieweg’s screenplay for Endzeit, based on her 2011 comic, won the Tankred Dorst Award at the prestigious Munich Screenplay Workshop in 2015, being selected by a jury as the best of her class. The 2018 edition of the Endzeit comic, in turn, is based on her screenplay. Vieweg says it’s the result of a learning curve.

“I had the opportunity to learn a lot about screenwriting, and I made use of that time to keep developing the story,” she says. “The original version is a short story, and I wanted to turn it into more of an epic experience, which had been the plan initially. But in the four months I had for my diploma project at the time, this wasn’t doable. With the new comics adaptation, I wanted to reclaim some of the freedom that you don’t always have working on a screenplay. I did a few things that were rejected in the screenplay and that I wanted to do in a particular way.” Adapting her own screenplay, Vieweg says, was also a means to assert herself as an author, to maybe ensure she won’t be forgotten once the film opens.

With this concern, Vieweg isn’t alone. There has been some debate recently in the German film industry on the lack of visibility, recognition, and participation of screenwriters. Vieweg says her experience in film has been mixed, but mostly positive.

With this concern, Vieweg isn’t alone. There has been some debate recently in the German film industry on the lack of visibility, recognition, and participation of screenwriters. Vieweg says her experience in film has been mixed, but mostly positive.

“I’ve received a lot of support,” she says. “I was able to convince quite a few people of my story and I’ve received some great criticism that I was able to work with. But making the screenplay as good as it can be was a struggle. I had to fight for things, and that’s something that I wasn’t used to before and that was hurtful, as well, because sometimes ideas end up in there that you don’t support. And as soon as you turn in the final draft, you’re not needed anymore. From that point on, a number of other people take over your story, without seeking your approval. But just to be clear: This is something that’s totally normal right now! I even had more of a chance to participate than some writers do. But the current debate has led me to the conclusion that just because something is normal, it doesn’t have to be okay for you personally. It would be good if things changed in the future. My impression is that the U.S. is a bit farther along on that score.”

In a (German-language) podcast late last year, Vieweg talked about how the story of her screenplay was interrogated for deeper meanings and messages at every turn.

“People like to view post-apocalyptic scenarios as parables about social issues,” she says. “As it should be. But I didn’t want to do the umpteenth eco-message, either. Although of course that’s in there, too, and that’s good! One point of contention, for instance, was the depiction of the town in which Vivi and Eva live at the beginning. That ended up looking way more military and grim than I’d planned. But this means more tension, as well. Which is why I did it this way in the comics adaptation, too, instead of sticking to my original idea of a Weimar ruled by hippies who solve all their problems by sitting down in a circle.”

Vieweg has mentioned zombie-film pioneer George Romero as a major influence on her first movie project. Another inspiration, she says, was the 2003 mystery thriller I’m Not Scared by Italian director Gabriele Salvatores.

“When I saw that one in the theater at the time, it was a revelation to me, in much the same way Naru Taru had been in terms of comics,” Vieweg says. “The movie covers just about everything that stirs my blood: kid heroes, a hot summer in the exuberance of nature, and horror elements. This film may be the ideal that I’m chasing. Maybe that’s why I’ve given my protagonist Vivi a kind of prayer, because there’s something similar in I’m Not Scared, as well. In terms of zombie films, I love 28 Weeks Later, above all. That’s the Holy Grail for me, where the zombie genre is concerned.”

Curiously, the type of genre material that keeps industries alive in other countries is virtually nonexistent in German film and comics. Sure, foreign genre work is being translated and distributed en masse, but most German-language genre work—the kind of commercial work that won’t require public funding to be viable—faded away throughout the 1980s, and the industries that produced it never came back. As a work of genre, Endzeit happens to be a niche project, in comics as well as in the film industry. Vieweg wonders whether that’s another part of the legacy left behind by the Nazis, and by the public outrage and legislation against “trash” and “filth” that followed in the 1950s.

“People still think this way even today,” she says. “Comics are for children and for stupid people. And genre movies like Godzilla didn’t find any recognition, either.” Vieweg points out that some of the seminal horror films of the 1920s, such as Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, were made in Germany—just like the frequently horrific fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, which continue to be well-regarded to this day.

“People still think this way even today,” she says. “Comics are for children and for stupid people. And genre movies like Godzilla didn’t find any recognition, either.” Vieweg points out that some of the seminal horror films of the 1920s, such as Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, were made in Germany—just like the frequently horrific fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, which continue to be well-regarded to this day.

“So what the devil happened there?!”, she wonders.

In a recent two-part documentary, Doomed Love (2016) and Open Wounds (2017), co-directors and co-writers Dominik Graf and Johannes F. Sievert examine the disappearance of genre from German film.

“German film is dead,” a voiceover supplied by Graf suggests at the very beginning of Doomed Love. “It has been funded to death, scripted to death, talked to death, produced to death, instructed and taught to death, reviewed to death, written to death, dreamed to death, it has celebrated itself to death and laughed itself to death, and it is totally unerotic. It has been mulled over to death. Has it ever been any different?”

According to Graf, German culture has been, since the Second World War, mortally afraid of confronting its own collective subconscious and facing the monstrous disquiet festering in its underbelly. Consequently, Graf says, there’s been a sense of incorporeality to German film for some time now—a lack of thrills, of sex, of violence, of the type of body horror that has resulted in great genre work in America and in Asia.

The auteur approach of the New German Cinema that dominated German film from the late 1960s through the 1970s, Graf argues, reached its zenith with the Academy Award for Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum in 1980, and had met its demise by the time Rainer Werner Fassbinder died. Its legacy, Graf suggests, is the submission to executives, critics, and the custodians of public funding: the collective superego of a new class of gatekeepers, inclined and instructed to find some types of material more desirable than others due to their perceived cultural merit, but rarely able to articulate the difference.

“At some point people started adapting reviews of their own films,” Fassbinder reportedly said about his fellow auteurs, not long before his death in 1982, in response to a question on the future of New German Cinema. (I’ve been unable to verify the quote, but it’s been attributed to Fassbinder by at least three prominent directors, which arguably makes it truer than if he had merely really said it, anyway.)

“At some point people started adapting reviews of their own films,” Fassbinder reportedly said about his fellow auteurs, not long before his death in 1982, in response to a question on the future of New German Cinema. (I’ve been unable to verify the quote, but it’s been attributed to Fassbinder by at least three prominent directors, which arguably makes it truer than if he had merely really said it, anyway.)

Since German comics weren’t being reviewed much to begin with, their makers, in the late 2000s, started adapting reviews of Maus and Persepolis instead. Not all of the resulting books have been terrible, but very few have managed to earn back through the weight of craft and substance—or in sales to paying customers, for that matter—the importance readily bestowed on them by publishers, critics, and cultural institutions.

In fact, German comics has, for a very long time now, been in a situation similar to the one Kim Thompson once observed in the U.S.

“What I see as missing from American comics,” Thompson wrote in 1999, “is that bulwark of solid, unpretentious, accessible genre fiction—a more or less undistinguished mass of okay-to-good comics that might catch your eye and give you a thrill, that loyal fans would buy out of habit, and anyone else might just pick up for the hell of it.”

In the 21st century, and in the 2010s in particular, the kind of bulwark Thompson was talking about has arguably been created in the U.S., with publishers like Image, Dark Horse, IDW, and a handful of others producing a variety of non-superhero genre titles. In Germany, there is nothing like it. Very few homegrown genre comics are made, and most of them are self-published or released through small-press outfits that barely break even.

In the way Vieweg taps into the subconscious of German culture and rejects the superego many of her contemporaries submit themselves to in order to appeal to gatekeepers, her work—both in comics and in film—has more in common aesthetically and thematically with genre filmmakers like Roland Klick, Roger Fritz, or Carl Schenkel (content warning: the trailers linked to contain strong language, lurid and gruesome imagery, and people speaking German!) than with a German comics mainstream represented by Kleist, Mawil, or Yelin.

In part, certainly, this is owed to the Japanese comics and animation that have influenced Vieweg, which are far less restrained by narrow concerns of good taste and cultural value than the German-language comics and film markets of the last decades. But this all points to the same conclusion: Basically, at some point, E-Kultur prevailed in the struggle of cultural ideologies. As a result, commercial storytelling traditions that remain alive and vital elsewhere have been lost and are all but wiped out and forgotten in Germany.

Likewise, when it comes to young-adult comics of any type, original German-language work barely exists, as Vieweg points out.

“There are comics for children and for adults,” she says. “For young adults, there’s manga only. My own comics are aimed at young adults, for that matter, but they’re read almost exclusively by adults.”

Yet, Vieweg is among a few German cartoonists who have resisted the gravitational pull of the German Graphic Novel—in these parts, unlike in the U.S., the term is strictly reserved for serious biographies, literary adaptations, and important works of historical and educational merit—and still find a measure of commercial success.

It’s not like many of the works that fulfill the criteria prescribed by German publishers, critics, bookstore managers, and public institutions end up finding an audience. It’s just that very few of those which do fulfill the criteria are very good, and almost none of those which do not fulfill the criteria even get the chance to fail on their own terms.

It’s not like many of the works that fulfill the criteria prescribed by German publishers, critics, bookstore managers, and public institutions end up finding an audience. It’s just that very few of those which do fulfill the criteria are very good, and almost none of those which do not fulfill the criteria even get the chance to fail on their own terms.

Like German film, after all, German comics has come to be extremely dependent on public money, and there are certain expectations that an aspiring cartoonist better not stray from too far if they want to be published, and funded. Which is all good and well and should be an option that’s on the table. But when it’s pretty much the only road left to be taken by someone wanting to earn a living with their art, the effect on the form can be stifling.

In another respect, meanwhile, German-language comics does appear to be prospering: It’s women who have been doing the most interesting work in many of the field’s subsections—as cartoonists, but also as editors and publishers.

To get a snapshot of the best original German-language comics being made right now, you can’t do much better than look at the work of Ulli Lust, Anna Haifisch, and Olivia Vieweg. German-language manga and Web comics, for that matter, have long been dominated by women. And the two most promising German small-press publishers at this juncture, Kassel’s Rotopolpress and Berlin’s Jaja Verlag, are owned and run by women.

“I think women are surprisingly well-represented in German comics,” says Vieweg. She doesn’t think she’s ever been personally discriminated against in the industry.

“No, I’ve been very lucky, to date,” Vieweg says. “Or if I have been put at a disadvantage, I haven’t noticed. I just think I’ve sometimes been paid less when working as a freelance illustrator, but in part that’s been because I didn’t have the nerve to ask for more appropriate rates. But I’ve been growing more sensible in that regard.”

A few years back, Vieweg said that if she were able to make films, she would do so. Now that she is, though, she’s not quite ready to kiss comics goodbye just yet.

“I do want to keep making films,” she says. “But I’ve also found a new appreciation for drawing comics. That’s where I have carte blanche.”

In the 2018 edition of Endzeit, Vieweg’s comics adaptation of her screenplay adapting her 2012 comic that originated as her diploma project, the episode in which Vivi and Eva encounter the Gardener runs 40 pages—four times as long as in the initial version—and ends on a very different note. Also, this time there is a plant-like quality to the decay of the zombie infection—its victims look less like their flesh is rotting and more like it’s ivy that’s creeping all over them. The Gardener isn’t explicitly named as such in this incarnation of the story, and the clues to her background are left for the art to convey, rather than verbalized. The Gardener is about to kill Eva, who has been infected by the zombie plague, but then she gives the two women a choice: In exchange for letting Eva leave and granting her a fighting chance, she wants Vivi to stay in the garden forever. This time, however, Vivi and Eva won’t submit to the choice they’re given. This time, there is a fight.

According to Vieweg, the character of the Gardener was another point of contention in her screenplay. She says the producers wanted to know what the woman stood for. The question was whether her in-betweenness embodied the state of the world they were depicting, or if she was more of a roadblock for the protagonists.

“When I drew the comic,” Vieweg says, “for me it was the latter.”