Nicole Hollander is a cartoonist, artist, writer, curator, and performer who is best known among comics fans for her daily comic strip Sylvia, which ran from 1981 to 2012, when Hollander retired the strip. Earlier this year Fantagraphics published We Ate Wonder Bread: A Memoir of Growing Up on the West Side of Chicago. The book is about Hollander’s childhood, the building where she lived, her neighborhood, and the people there. It’s about stories from childhood that she’s never forgotten. It’s also a very different project from Sylvia. As one whose view of Hollander’s work was dominated by that strip, reading the memoir was a very experience. The book is colorful – literally and metaphorically – in a way that Sylvia was not. The book is a combination of text and pictures, though not a graphic novel. It was a new way to work for her, according to Hollander, and she clearly enjoyed being able to experiment and find a new way to tell these stories.

Nicole Hollander is a cartoonist, artist, writer, curator, and performer who is best known among comics fans for her daily comic strip Sylvia, which ran from 1981 to 2012, when Hollander retired the strip. Earlier this year Fantagraphics published We Ate Wonder Bread: A Memoir of Growing Up on the West Side of Chicago. The book is about Hollander’s childhood, the building where she lived, her neighborhood, and the people there. It’s about stories from childhood that she’s never forgotten. It’s also a very different project from Sylvia. As one whose view of Hollander’s work was dominated by that strip, reading the memoir was a very experience. The book is colorful – literally and metaphorically – in a way that Sylvia was not. The book is a combination of text and pictures, though not a graphic novel. It was a new way to work for her, according to Hollander, and she clearly enjoyed being able to experiment and find a new way to tell these stories.

In her introduction Alison Bechdel argues that the book is not simply a memoir but a superhero origin story, offering insight into not just Hollander but her most famous character. “Sylvia paved the way for later generations of women cartoonists, but it was life in a chaotic, joke-filled West Side six-flat that paved the way for Sylvia.”

Why did you decide to write a memoir in the first place?

I think the computer and Google made the decision for me. I was at my computer and I put in the apartment address of the building I lived in as child. It was all there! The side of the street I lived on was still there, the building was there! The stories were all there. I just started writing. I had a residency at Ragdale in Lake Forest, Illinois in an enormous beautiful studio on the prairie. Before I left Chicago, I bought huge sheets of charcoal paper and charcoal. When I got to the studio, I stapled the pages to the wall and just started drawing and writing the memoir.

There was a feeling of freedom that I never got with a cartoon strip. I wrote six cartoons a week. I read a lot about politics and politicians. I was a feminist, I cared about women and what we could and couldn’t do. I created a character Sylvia, who was afraid of nothing. She was quick-witted. Of course she was, she had a week to think of the perfect retort.

So you specifically set out to write about your childhood and your neighbors and that neighborhood.

Seeing my childhood home on Google was the catalyst. I remembered the neighbors, the way we lived, what we ate, our friends and family and one story after another. I really can’t swear to the accuracy of these memories, but I will if you insist! Drawing was my first love. I drew and drew. I was hard to get me out of the house. In grammar school I was the class artist. If it was Thanksgiving, I was drawing a turkey on the blackboard. Once you are named the class artist, it’s impossible to depose you.

It was a shock to see that all these buildings were still there with the exception of one building. That started the story because I could see all the buildings and remembered those earlier stories. The later stories are harder to pull out of yourself but the early ones, I think one just leads to another. I wish I could say it was this perfect outline – this is my life, this is my childhood – but it didn’t work that way.

You mentioned that you started working on the book during a residency. What did you do on that residency?

You mentioned that you started working on the book during a residency. What did you do on that residency?

I must have given them a project. Maybe I said “graphic memoir”? Ragdale was pretty loose about how the project was described in relation to what actually happened in those two weeks.

The worse and best thing about the residency was dinner. The chef, being oversensitive to gluten, would describe in minute detail what each dish contained. It drove me crazy. I was not allergic to anything – except being delayed in eating dinner. I had fantasies about screaming “I am not allergic to anything! If you are, just stay in your room and eat crackers!”

A good memoir is about rethinking and examining one’s life. You may have been reminded of all these stories when you saw your old building, but what was the process of figuring that out?

You come to understand the relationships that you had with people. That gets examined and then what happens is you have part of a story. You start having to dig deeper and that’s the part that’s not so clear. You think, was there something else that happened here? What happened? You remember a tiny glimpse of something.

I remember going out to the alley and opening the door and seeing what I thought was a huge rat – and still having to walk through the alley. I remember not knowing who to ask, what do you do if you want to make flowers grow? I just came to the idea that you cleaned it up and then flowers would grow. I learned that’s not how it goes. [laughs] I should have known from seeing the old man next door because he was out in the garden all the time. What did I think he was doing? I don’t know. He was a grownup so of course he could make flowers grow and I couldn’t. I drove my father crazy asking him about flowers and one day he went out and bought flowers and stuck them in a pot on the back porch. I was so angry at him because I knew that wasn’t what happened. [laughs]

Right. Why point out how little I knew? But he did.

How did you go about deciding what to write versus what to draw?

Certain things suggest themselves to draw. The image of the woman who lived on the third floor and who was pampered by her family so that she wouldn’t run away. She was a grownup but they provided her with all sorts of fancy furniture for her bedroom. Wall to wall carpeting and a dressing table with perfumes.

Usually children slept in the dining room and parents slept in the bedroom but she had the bedroom because she was older and they wanted to keep her there. Then I started to remember how we were so in awe of them. They dressed a certain way before they went out. I wrote about this because we would go up and look at them like they were royalty. They had robes on and we wondered when they were going to get dressed. Because you couldn’t go out in a robe. They would say, “we’re all dressed underneath.” These were concepts that were really foreign to all the families on the block. People just put clothes on, but these two women were showered and made up and they had exotic perfume. I remember thinking that certain kinds of perfume were only for people who had more money than we did. I had no idea if that was true.

I actually got some things wrong. This is pretty amazing to me. I got letters from two girls I knew as a kid. We were all the same age. I had no idea what happened to to one of them. She was the girl whose dress caught on fire and whose mother ran out and put the fire out with her hands. I showed her mother with bandages on her hands. She emailed me. I was utterly amazed. She said, you made my mother look just like she looked. I thought, that’s not possible. [laughs] I have no image of your mother. I see her as saving your life, but I don’t see her face. I don’t know if both of us were colluding in making that kind of wonderful memory. We have no idea. I think that’s maybe what memoirs are unless you’re one of those people who wrote every single thing down in a notebook. You must know other people who have written memoirs.

Yes, and it’s always complicated.

That’s the other thing you think your memories are perfect and clear. She said to me, it wasn’t that person who was married to the stalker. He was married to a tenant of my grandmother’s. I didn’t even know she had a grandmother. [laughs] So I don’t know. These people who don’t worry about writing it down did they keep notebooks? Do they know it was exact? Do people have doubts about their memories?

From talking to memoirists, a lot of them do.

Good. I’m not the only one. [laughs]

I keep coming back to that cover image.

Of my sister, yes.

How did you ultimately decide on the title and the cover image?

The cover image went through many changes. I was focusing on the title, which also went through many changes. First, I think it was “When We All Ate Wonder Bread” then it was “When We All Ate Wonder Bread and finally “We Ate Wonder Bread.” I loved making those tiny changes and seeing much just a small change changes everything. I started with my image as kid remembering how we were warned not to squeeze the wonder bread and that seemed forced. Did that image really stand for the time for what the neighborhood was like? Did it have flavor of being kids? Then I thought of my sister wanting to go outside to play in the snow and have to rely on my mother to get her in the snow suit and being impatient and feeling she was big enough to do it herself. I loved her impatience and finally just jumping up and pulling the hanger and the snow suit down and having it land in her eye and do no harm. That’s like a piece of magic. And my mother screaming, and yet able to pull out the hanger, and her friend acting like it was all in a day’s work. “Good job, Shirl”.

I keep thinking of these stories that I’ve heard relatives tell over the years – I’m sure most people have this experience – of these crazy stories from when they were young and it’s nostalgic but they’re also saying, it’s a wonder we survived.

I keep thinking of these stories that I’ve heard relatives tell over the years – I’m sure most people have this experience – of these crazy stories from when they were young and it’s nostalgic but they’re also saying, it’s a wonder we survived.

Usually in their minds those were gentler times, I think. Like when people could go and sleep on the beach when there was no air conditioning.

Everybody says, that couldn’t have happened. But no, it’s very clear to me. My mother did what was necessary to do while screaming. She just did it and then since there was no consequence, everything went back to normal. I don’t remember there being a consequence. My sister certainly doesn’t remember.

Did you ask your sister or other people about these events while you were writing the book?

I think writing this was very good for my sister’s and my relationship. I remembered how much younger she was than I was. Her memories of these things [in the book] are almost nil. It’s almost as if she was born into a different family. She remembered the name of the boy that shot the pencil at me – where I fantasized that I became a blind musician. He had a younger brother and the brother was her friend. I remember the brother was sweet and didn’t look like anyone in the family, but he was a child. There’s nine and a half years difference between us.

That’s a lot of time.

That’s a whole lifetime. It was a different world. I was going to college and she’s still a child. It’s nice to grow up when you’re both much older and to see each other as two adults who are interested in hearing the stories of the other one and have a context to put it in.

The book is colorful in a way that Sylvia never was. Literally. Sylvia was black and white and the book is in color.

I loved that about Sylvia. That allowed me to make mistakes because you could just put white Avery labels over the mistake and then rewrite it and all the camera would pick up was the black and the white would drop out. Doing the drawings for the memoir were much more fun.

It seemed like you had fun making the art for the book. Why did you decide to approach the art like that?

I thought it would give it another dimension and make it more interesting. There were a lot of things that involved the building and the people in the building. Sylvia has a very small world. It’s a small black and white world that consists of her bathtub and her television and the words that come off it. When I did the memoir it was a real world that I remembered and I could put color in it. There were no restrictions in that way at all. I don’t think I even thought a moment about not putting color in it.

When you started drawing, what kinds of material were you using? What size were you working at?

I started it at the Artists Colony and I used really large sheets of beautiful paper. I just started drawing. When it came to have to actually be produced, I had to think about lots of things again. Some of the images were too big. Also I did it like a sketchbook so I had to redo some of the drawings because they were just too rough. I did leave some of the rough ones in. My designer said he wanted to show how I drew the house and people’s apartments. They were really like a child’s drawing. We left that in.

You had a sense of how you wanted the book to look and feel from the start.

Yeah. Before I became a cartoonist I went to school for fine arts so I did all sorts of big images in color. I think I wanted that to be in there. I liked color, although I had been restricted for 35 years to black and white. Sylvia was so free because I felt I could write anything I wanted. The words could be whatever I wanted and I had this limitation that only the blacks showed. That was very helpful so I could make changes and make mistakes and go back. As a painter, you paint and paint and there comes a point where you have painted too much and it doesn’t look good anymore. You either have to get rid of it or start a new painting and a new thought. They’re very different experiences and I’m really glad that I had both of those things to call on.

What made you decide on the style you did, a combination of text and pictures and comics?

What made you decide on the style you did, a combination of text and pictures and comics?

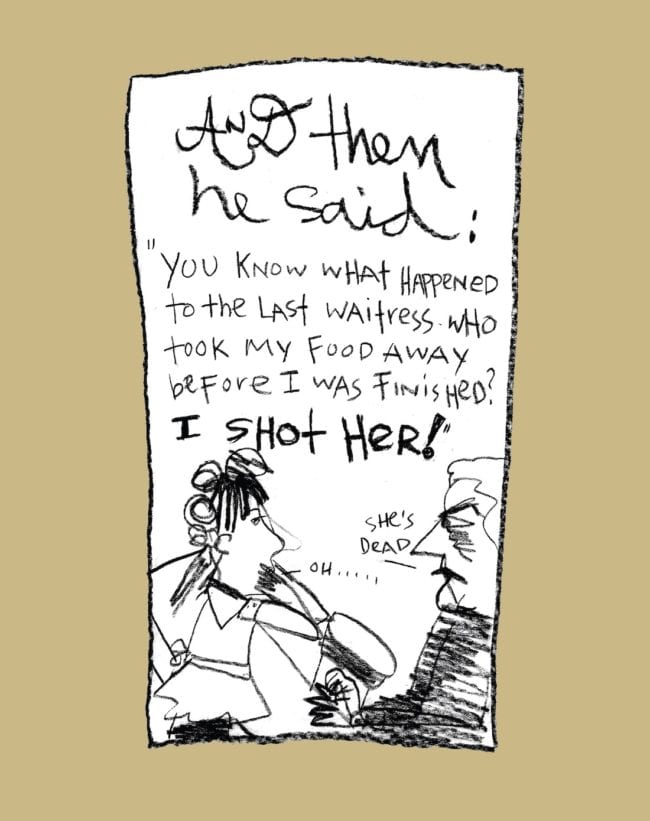

My cartoon strip Sylvia was text and image. It always started with the writing. What did I want to say, what was the set up, where was the punch line? It was about timing. The slow work up and the pause and then the pay off. Jack Benny was a comedian from my childhood. I first heard him on the radio and then on television. He seemed to have all the time in the world to set up his story. He didn’t hurry. You were in good hands with Jack Benny

But why did you want the book to look like this instead of making a graphic novel?

Personally I’m just not so interested in the graphic novel. Of course I love many of them and many cartoons. I was just thinking of Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For and she had so many characters and they had their whole lives and movement. When I thought about graphic memoirs, I thought hers was loose and exciting, but I didn’t want this tight thing where you worried about the panels and the panels working out. I didn’t want to be constricted in that way. As you move your hand just the movement of your hand and what accidentally happens, you might make a story about it that’s better than the story you were thinking you were going to make. Or it seems better at the moment.

Related to that, you said that you had to redraw and rethink some of the artwork. Were you ever thinking about how you wanted the pages to look as you were writing and drawing? Or was that part of the final stage of the process for you?

People don’t think about the fact that you have a designer. I’ve worked with this friend for years. He was looking at it and saying, you’re showing too much here, or this is not the drawing it should be, why don’t you rethink it. It’s not like a notebook that you’re writing secretly under the covers. It has to be shown to other people and they help you. Sometimes you say, that’s too bad. [laughs] Because I’m the boss of me, as children will say. It is a little bit more of a group effort than writing alone in your room and not showing it to anyone. I was conscious of what I was doing. If that makes any sense.

You’re saying the designer played a similar role to the editor.

Exactly. He was the visual editor, in a way.

You retired Sylvia in 2012. What was that like? Do you still feel the urge to draw a strip, to utilize her voice.

I think I always think in Sylvia’s voice, which is really a combination of my mother and her deadpan friend Esther. Nothing phases Esther. My mother was funny without giving it a second thought, yet she was always worrying about something, always breaking a glass. Once she tried to glue a broken fingernail back using epoxy and had to go to the hospital to have the glue removed, her finger repaired. Luckily she worked at the hospital – convenient when you’re accident prone .

I didn’t do a cartoon a day. I worked on a week at once. I was thinking about newspapers and Sylvia watching T.V. and writing a lot and then finding the joke. Drawing her apartment, the lamps, the furniture, was part of it. I worked the drawing over and over and used Avery stick on labels when the drawing and the writing got messy. The wonderful thing about black and white cartoons was that the camera only picked up the black. You could white out a lot and still have the comic look clean and clear in the end.

Besides this book, what have you been working on since Sylvia ended?

I started out as an artist/illustrator and I find myself more drawn to performance and writing. In the last few years I’ve been writing with a friend and performing stories. We are very different, but have a similar vision of storytelling. I wanted to call our performance “A Pentecostal and a Jew walk into a bar.”

Was a writing a memoir more like writing a performance piece than writing a comic strip?

I did write a prose memoir, called Tales of Graceful Aging. The gods of great expectations looked down at me and thought, “what if we have her book come out at the same time that the Nora Ephron book I Feel Bad About My Neck comes out?” I always thought “I Hate my Neck” is a better title, but I’m hardly a good judge, because her book blew me out of the water.

I think I work more creatively and more freely when I combine writing and illustration, because I always drew. It was later that I began to write. When I do performances – with a friend – writing and then performing works well for us. I think I must do two things at once or I get confused. The cartoon strip had a format. The illustrated memoir could be anything, almost.

Yes, I think writing for performance is more like a doing a memoir because your past comes up into focus the more you write and rework, and you see the action. But where does timing come in? Because without timing you’ve got nothing! I like working with someone else because along with the audience responding, your partner is responding. We sometimes laugh as if we heard it for the first time. We both hear badly, so often we are hearing the line for the first time.

Do you enjoy creating but having this give and take as part of the process, whether with an editor or designer or your friend?

I do, because you’ve written something that’s completely yours and then you try to make it into a story that two people can read on stage. It has the same theme, but it’s not the same story at all. That’s really fun because some things happen that you don’t know are going to happen. She also worked as an editor so she would go through it. I’ve made up forms of grammar that don’t exist so something has to watch me. [laughs] My possessive plural are not always accurate.

But similar to how you wanted to tell this memoir, you don’t like being constrained by form, but you also need someone to go, maybe do this, or that works better.

But similar to how you wanted to tell this memoir, you don’t like being constrained by form, but you also need someone to go, maybe do this, or that works better.

Yes. Why don’t you just take a second look at that. [laughs]

I may even be wrong about this, but the graphic novels that I’ve looked at seem to be constrained by those panels. They have lines around them. They have spaces between the panels. It seems very tight to me.

So you don’t miss making a daily comic.

No. But I miss the reason to look at a newspaper in a certain way. I looked at it in order to make a comment about it. I hardly read newspapers anymore. I shouldn’t say that. I get up every morning and read The New York Times on my phone and I listen to The Daily. I have to have coffee and I have to read that, but I don’t miss drawing the strip. I got in the habit of knowing what was going on. Even if I wasn’t drawing the strip, I had to know.