This interview was originally published in The Comics Journal #252 (May 2003).

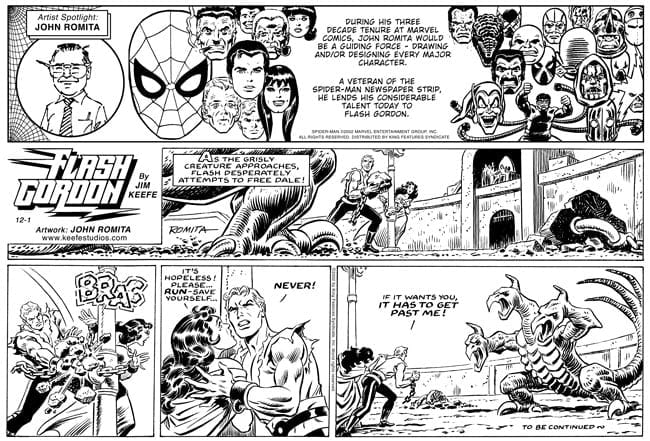

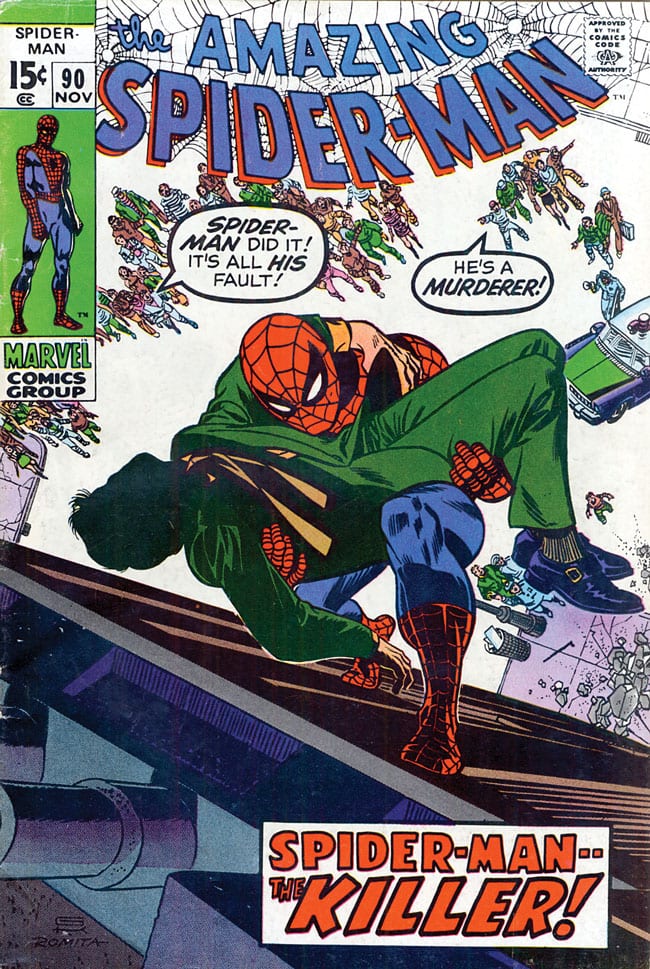

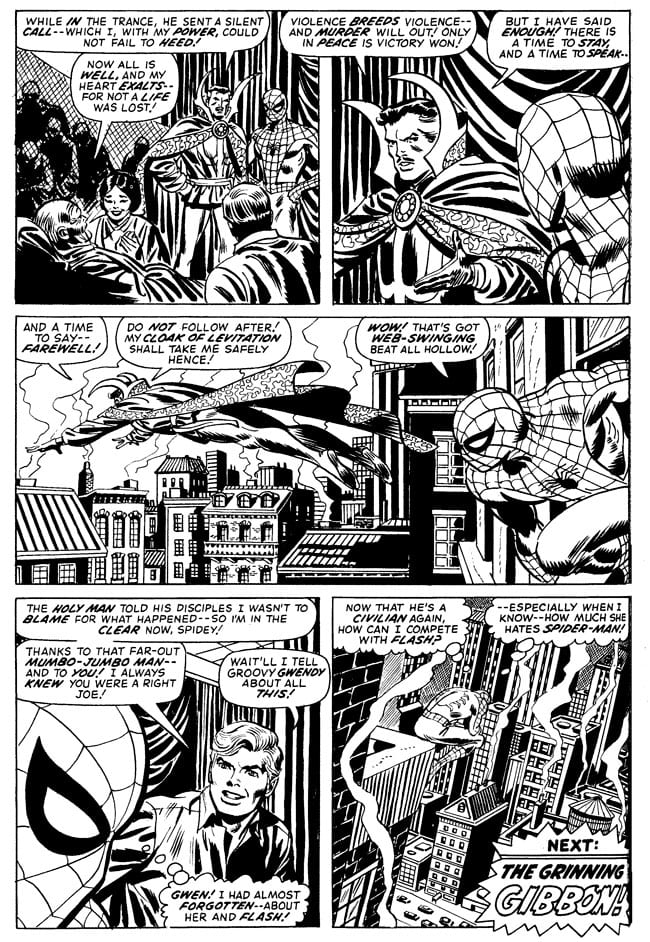

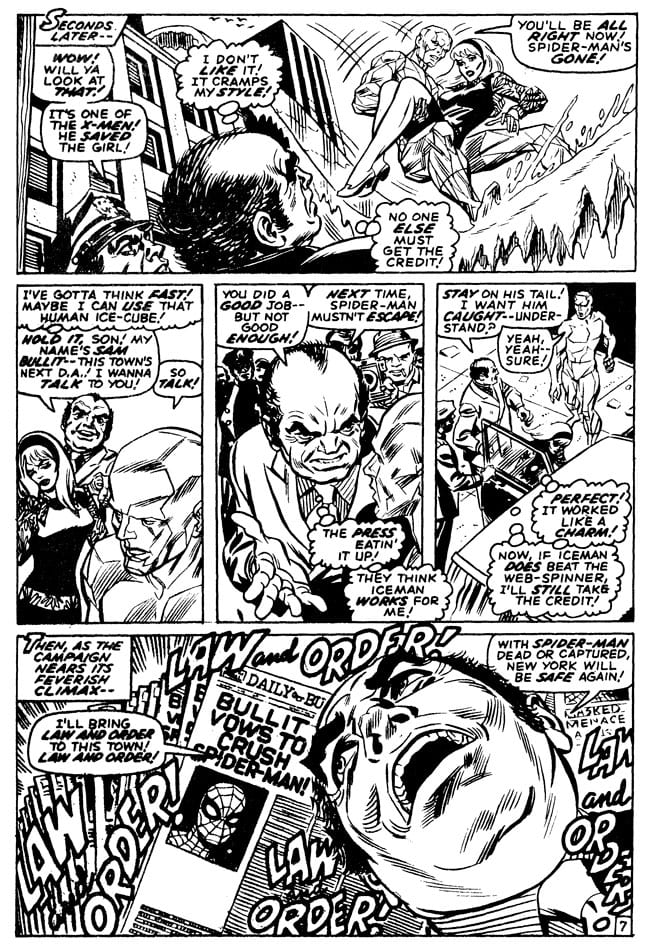

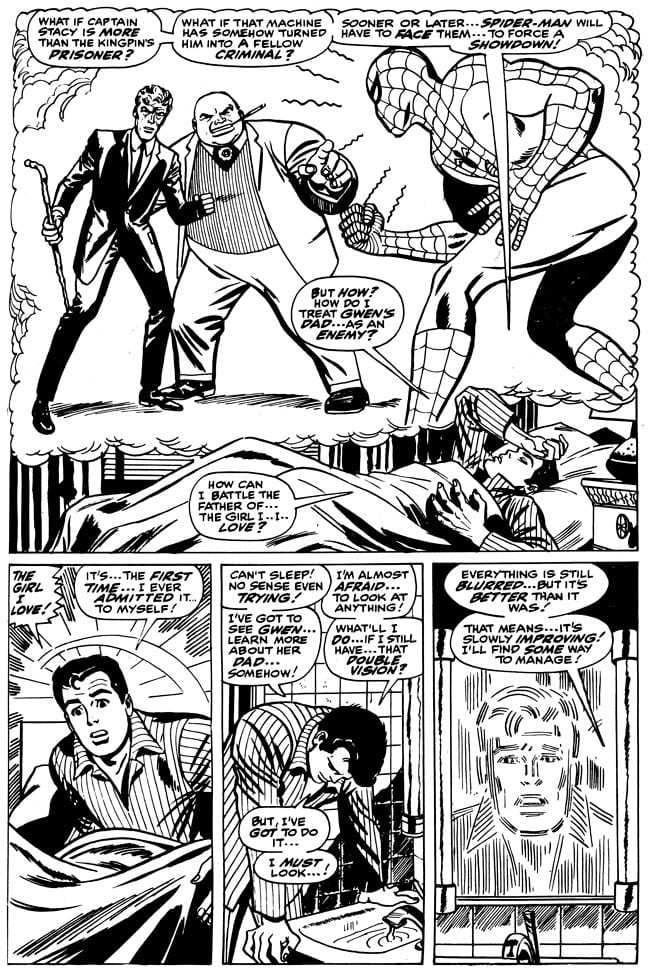

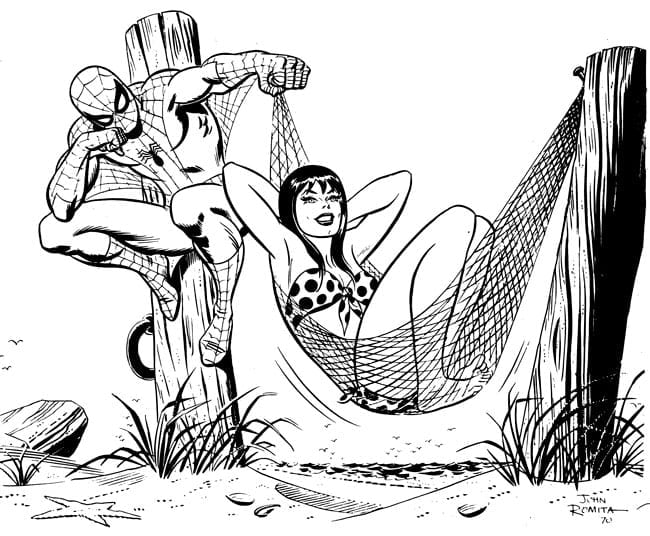

John Romita is best known for his 1960s run on The Amazing Spider-Man, and rightfully so. The Brooklyn native was brought on as a replacement for the character’s co-creator, artist Steve Ditko, at a crucial time in Marvel’s emergence as a publishing line and pop-culture phenomenon. Stan Lee never made a smarter move. Romita gave the adventures of Marvel’s flagship character a look that mixed the heightened everyday appeal of romance comics with Marvel’s across-the-line take on Jack Kirby’s dynamism. Rarely has an artist working in the American comic-book mainstream made as strong a graphic impression on a character not originally his own. No matter which version of Spider-Man readers worldwide prefer in terms of story, it is John Romita’s basic visual interpretation that lingers on in memory: Peter Parker on the motorcycle, clad in a black turtleneck, physically traumatized by a series of sharply and logically dressed villains, finding a moment’s peace with elbows crooked to receive the hands of all-time Good Girls Mary Jane Watson and Gwen Stacy. Romita’s work at its best was fashionable, sharp and fundamentally sound, playing no small role in vaulting the character and the company to the top of the industry.

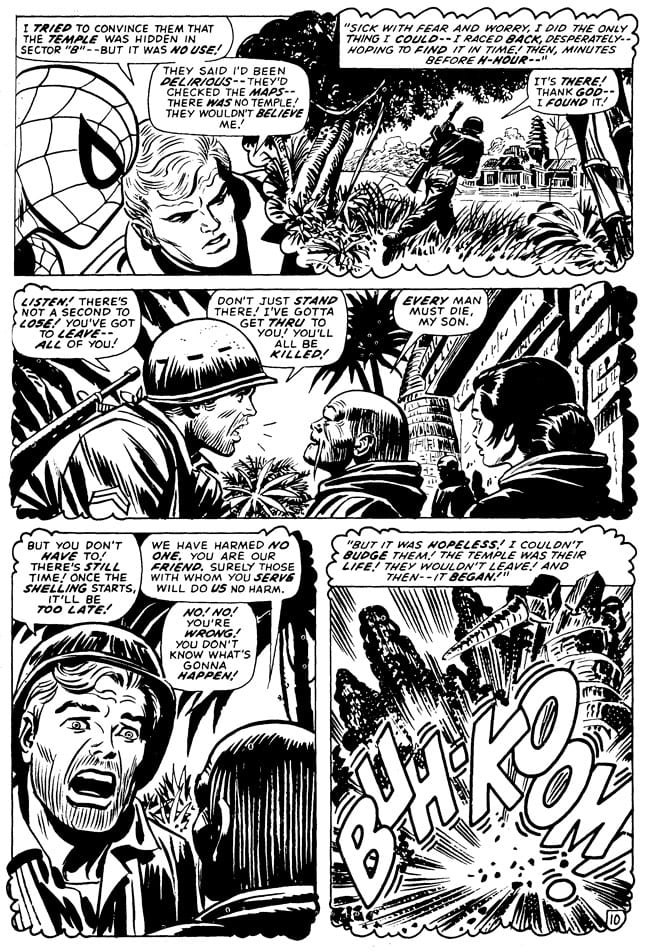

Romita was born in 1930, and in many ways, his career is emblematic of the second wave of American comic-book creators. Like many comic-book cartoonists, Romita trained in various New York-area schools and worked as an illustrator in the Armed Services. His first job in comics was as a ghost artist in one of the industry’s flush periods, but he soon made a name for himself as a dependable worker who could pick up on various popular styles — the chance to add to the basic visual vocabulary and style palette of comics lost by virtue of his relative late arrival in the field, a missed opportunity Romita speaks of with eloquent regret. He worked for DC when it was a leader in the field and for Marvel when it overtook DC. After his heyday as a penciler for the Marvel line, which also included lovely turns on Daredevil and Captain America, Romita became art director at the company, expanding on an informal role he had played in the office. Even as the formal penciling jobs dwindled, Romita remained Marvel’s most important designer, extremely facile with covers and costumes. Romita worked closely with some of the best artists in the industry’s history, such as Gil Kane, and more than most men of his considerable talent understood what made various artists work on the page. Romita has given back to the industry that employed him in any number of ways, including the fruits of a second generation. His son and namesake has been a successful artist for two decades now, including popular runs on the Spider-Man character, making the Romitas one of the first families of mainstream comic books. The father’s pride when speaking of John Jr. is genuine and palpable, even over the telephone.

Our interview was conducted during the early part of the Christmas holidays, and he was occasionally reminded of the status of soon-to-arrive houseguests by longtime wife Virginia. He was affable and forthcoming, and in his voice and good humor he cast his own artistic journey and the industry’s past in an attractive but sensible light similar to the effect his most fondly remembered comics had on generations of young people, my own included.

— Tom Spurgeon

[This interview was transcribed by Tom Spurgeon and copy-edited by him and Milo George.]

Doing His Share

TOM SPURGEON: How often do you get to the drawing table these days?

JOHN ROMITA: As little as possible. [Laughter.] That’s why I didn’t get the [TCJ] cover done in time for solicitation. I feel terrible about it. I should’ve gotten it done quicker, but between Thanksgiving and Christmas confusion, I thought I was going to have two weeks or a week to get things done, and it ended up a couple of days between one thing was finished and the next thing started. I’ve had relatives here after Thanksgiving, and then I’m getting relatives here early for Christmas. So things have been up in smoke.

SPURGEON: It’s a short holiday season this year, so I think a lot of people are getting squeezed. Do you draw for pleasure still at all?

ROMITA: The only thing I’m about to embark on is to try some computer-generated art. But that’s only because it’s been in my head for five or six years, that I wanted to try it. I don’t know if it’s wise, and, of course, the equipment costs a lot of money, and I don’t know if I’m going to have the patience to sit at the computer for long hours. Right now I just use it for e-mail and the occasional reference call. That’s the only thing I’m planning.

I did a Supergirl cover for DC, only because a former Marvel editor was up there, and asked me to do it. I did it as a favor. But I’m trying to avoid work. [Laughter.] After 55 years I started working when I was 14, and when I hit 66, I left the office but I kept working the last five or six years. And I said, “You know, this is ridiculous. Almost 55 years I’ve been working. The hell with that. I did my share.”

SPURGEON: What was it you did at 14?

ROMITA: I was a messenger in Times Square. It’s documented in one of Roy Thomas’ nostalgic visits. He did retrospective things while he was editing at Marvel. He did a World War II story, and he showed a scene of me delivering packages in Times Square, believe it or not. [Laughter.] I wish I remember what book that was.

SPURGEON: How did a Brooklyn boy end up working down in Times Square?

ROMITA: I went to school in the city. When I was 14, I embarked on a long subway ride to get to the School of Industrial Arts in the city. I wanted to go to that art school so badly, so my mother gave me the permission. Somebody asked if there’s anybody interested in making 60 cents an hour as a messenger, and I jumped up like an idiot. [Laughter.] For the next few years I worked there. I was a little mad at myself, but I needed the money.

SPURGEON: You always drew as a kid?

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. I was drawing since I was about 5.

SPURGEON: Was it very much supported in your family? Were there artists in your family?

ROMITA: They were supportive. We were musically oriented. Everybody loved singing, and I’m the only one in the family who couldn’t sing. They always supported me. But they never believed I would make a living as a comic artist. My father used to say, “Sure, you want to draw, you can draw all you want, but you’re not going to make a living.” He expected me to become a baker and drive a delivery truck.

SPURGEON: How long did that last?

ROMITA: He talked about it all during my adolescence. My mother used to shake her head while he wasn’t looking. [Laughter.]

SPURGEON: Were you known in the neighborhood as the kid who draws?

ROMITA: I used to draw on the sidewalks of Brooklyn. Believe it or not, I used to get chalk donated from all of my friends. I would do drawings all day long, when there was nothing else to do. There was not much else to do — no television, and spring and summer and fall I’d be drawing on the streets. The blacktop was a great blackboard for me. I once did a 100-foot long drawing of the Statue of Liberty. It was a good exercise, come to think of it, hunched over and drawing. I did everything. The whole thing. The pedestal, the full statue, the torch — I went from one manhole to the next, which was about a hundred feet.

SPURGEON: I imagine the impermanence of that might have prepared you for comic books.

ROMITA: When it rained, everybody used to say, “Oh, there it goes.” I would just do another drawing the next day. It didn’t matter.

SPURGEON: You drew in school?

ROMITA: In school, I did the usual things. Every holiday, starting with Lincoln’s birthday and Washington’s birthday, I would do silhouettes of the presidents and other kids would cut them out. I would do backdrops for school plays, and scenery — that kind of stuff.

SPURGEON: What was your curriculum like at Industrial Arts?

ROMITA: It was an innovative idea — and by the way, a lot of my colleagues, the comic-book artists from the ’40s and ’50s, graduated from that school. Carmine Infantino, Joe Giella, Sy Barry, almost all of my colleagues went to that school. Just a couple — John Buscema and Mike Esposito, maybe others — went to Music and Art. Music and Art was an interesting school, but it taught more of the fine arts and printmaking than commercial art. I went to the one that was commercial because I knew I had to make a living.

SPURGEON: You were taught by professional artists there.

ROMITA: That was the theory. It was wonderful. They were all excellent, excellent teachers and wonderful role models because they were all practicing, earning artists.

SPURGEON: Was it at this point that it locked in for you that you could make a living doing art?

ROMITA: Teenagers are very strange. You don’t have to really convince yourself; you just have this vague impression you’re going to make a living someday. Even if I thought, in lucid moments, that I probably wouldn’t make a living as an artist, I always thought that this was something I like to do, and I’ll always be able to do it, and if I don’t get work at it, I’ll do production or something like that. One of the things that was good about that school is that it taught you lettering, mechanical drawing, sculpture and photography; the foundation course the first year was very, very complete. It taught me all sorts of things. Like the rest of the class, we would grumble and say, “What the hell are we doing photography for?” Or show-card lettering. But the truth of the matter is that everything I studied in that foundation year has come to my aid in comics. Almost immediately when I got into comics, I was using lettering, I was using perspective, I was using mechanical-drawing techniques. I only went there for three years, because I wasted my first year of high school in a local junior high. So I went to Industrial Art at the tenth-grade level, and I only did the tenth-, 11th- and 12th-grade years. To my eternal regret. I should have had the guts to take a final year. Another year — I don’t know if they would have let me. [Laughter.]

Analyzing Comics

SPURGEON: You were born in 1930, so you would not have been in the first generation of professional comic-book artists.

ROMITA: No. Another one of my regrets. It really is. I always felt that I became a follower of necessity because they had already done the ground rules. And I became a guy who was just following everybody else’s lead. I think I would have been more of a pioneer and more of a person in my own right rather than a follower. I think it stamped me forever. No matter what success I’ve had, I’ve always considered myself a guy who can improve on somebody else’s concepts. A writer and another artist can create something, and I can make it better. I don’t know the name of that company that advertises all the time, “We don’t make the material, we just make it better.” You remember that commercial? That’s the way I’ve always thought of myself. I don’t consider myself a creator. I’ve created a lot of stuff. But I don’t consider myself a real creator in a Jack Kirby sense. But I’ve always had the ability to improve on other people’s stories, other people’s characters. And I think that’s what’s made me a living for 50 years.

SPURGEON: You would have been right at the best age to experience that first wave.

ROMITA: It was wonderful, that first wave. I was an avid reader. I remember everything that was done. I remember George Tuska: When I was 9 and 10 years old, George Tuska was doing stuff for Lev Gleason. I remember Jack Kirby’s work, I remember Captain America #1. I was about 8 years old when Action Comics #1 came out. I bought two copies of it. I don’t know what reason I gave my parents, maybe it was an accident. I had two copies, and I kept one in a wax-paper bag as a protector. So I was way ahead of everybody else on that. [Laughter.] The other one I traced to death. The cover was absolutely unviewable because I’d just traced it forever.

SPURGEON: You were making distinctions between the artists?

ROMITA: I was aware. That was one of the things that I accepted without thinking. In retrospect, it was a blessing. If you’re 10 years old and you’re talking with your friends about comics. I used to hear my friends say, “You don’t think somebody drew every panel in this book. This is drawn mechanically.” I’d say, “No, they’re doing the drawing.” So I was aware that people were doing 150 drawings a month on these stories, and they were not aware. They always thought it was some kind of trick of photography.

I was also aware of every trick that everybody used. When Jack Kirby’s Captain America started bursting out of panels, I was aware that that was smarter than the normal, run-of-the-mill, dull stuff where every figure was trapped in a panel. I had a power of understanding. For instance, when I was 13 and devouring Milton Caniff and Terry and the Pirates, I was aware of every little trick he did and realized they were tricks. Where he put his background elements, where he put his foreground elements, where he put accent and shadows. I was aware of every single thing. Where the clouds break on the mountains. Everything. I’m talking about 13 years old, and I’m transmitting everything that Caniff was doing; all the cleverness was going right into my brain. [Laughter.]

SPURGEON: Was it his facility that appealed to you, that he was a master cartoonist?

ROMITA: He had a really simple style. It was immediate to me. I loved the fact it was so lush. In other words, it was so powerful with blacks — nice big juicy blacks. Other people were doing linear work, the normal cartoonists were doing linear work that without color looked really flat. His dailies were excellent, and his Sundays were even better. The thing that gets me about Caniff, and which stamped me also as a storyteller rather than an artist, is that I would always start out looking at Caniff for the artwork. I would devour the artwork for an hour, and then I would get lost in the story. Down through the years, whenever I look back through my Caniff collection, I start looking at the drawings, admiring them and enjoying them, and by the third or fourth panel, I’m hooked on the story. And even though I’ve read it ten times, I will read it again. Because he was more of a storyteller than he was an artist. He was a wonderful artist, but he was a great storyteller. He was a filmmaker on paper. And that stamped me as a storyteller. From that moment on, I instinctively realized that storytelling was more important than drawing.

Santa Claus and Stan Lee

SPURGEON: Was entering the comics field encouraged at Industrial Arts?

ROMITA: Interestingly, there was a cartoon class before I got there. There were only three people enrolled in the cartoon class when I got there in ’44. Actually, it was ’45, because the foundation year I didn’t have a specialty. When I chose my major in ’45, there was not enough of a cartoon class. So, they stuck us in the corner of the illustration class. It happened to be a book-illustration class, which I thought was rather old-fashioned, but I learned to respect it. A wonderful book illustrator named Howard Simon was the instructor. He had me absolutely enraptured with his instruction for that first year. But I got hooked a little bit on magazine illustration because it was in color. And the second year I switched to magazine illustration. It had an excellent instructor named Ben Clemons. So I forgot my cartoon plans; they were completely lost after the first year of book illustration. Then magazine illustration strayed me even further from it. I didn’t think of getting back into cartoons. I decided to become an illustrator.

When I got out of school in ’47, I went to work at a litho house. I did Coke bottles, Coke glasses and Santa Clauses. I was just an office boy, but I was doing touch-ups on some major artwork.

SPURGEON: This would be in the style of Sundbloom?

ROMITA: Yeah. Sundbloom and Anderson. Beautiful, lush, sunlit figures — remember?

SPURGEON: Sure. That was really the end of the golden age of magazine and advertising illustration.

ROMITA: It was the golden age: Robert Fawcett, Al Parker, all the wonderful, wonderful illustrators of the ’40s in the Saturday Evening Post. I lived in the Saturday Evening Post for five years. I thought I was going to be another Robert Fawcett. As an illustrator, I started drawing in that style. I didn’t have the knack for painting that I had developed in my first three years in litho, I had gotten pretty good with some painting. But then I started to slip into more of an illustration style in line and color.

SPURGEON: Did you have the same kind of analytical approach to that kind of art as you did to the comics art?

ROMITA: Yeah. I also judged artists by their design sense and their characterization. So the narrative was still there lurking because a good illustrator has to tell a story, but some illustrators disregarded that and just did show stuff. They were showing off their technique and their color. The ones that appealed to me were the great illustrators.

SPURGEON: How did you end up getting back into cartoons?

ROMITA: When I was still at the litho house, I met one of my fellow SIA graduates on the train. We talked and, before I got off the train, he said, “You know, I’m working for Stan Lee.” He was an inker. He was making a living as an inker, making a nice buck. I was making $25 a week, and I think he was doing $150 a week. He was bragging to me, and he was just an inker! He said Stan Lee was looking for guys to pencil, and he could get more work if I turn in pencils. So, he asked me to ghost for him. I would pencil for him, and he would represent it to Stan Lee as his own. So I ghosted for him for about a year and a half. I was working for Stan Lee for that year and a half, and Stan Lee didn’t know me. Until I got drafted. After I got drafted, I spent time in Fort Dix and got assigned to New York on Governor’s Island in the recruiting poster department — which was a lucky break, completely out of the blue. I got back into illustration that way. I was doing comics in my spare time. And while I was in the Army, I went up to Stan and got work on my own.

SPURGEON: He was in the Empire State Building office at that time?

ROMITA: He was in the Empire State Building when I first started working for him, and I can’t remember where he was after that. But the first time I was working for him as a ghost he was in the Empire State Building. I remember many times waiting outside the Empire State Building for my partner to tell me how the work was accepted.

SPURGEON: Was this a common practice?

ROMITA: There were a lot of guys ghosting. It was a common practice in syndication, anyway. A lot of inkers were very quick as inkers but not good storytellers, or they couldn’t do it fast enough even if they were good artists. They weren’t fast enough. The ones that were fast made a living as pencilers. They needed something to break the ice, to get the work on paper and then they could ink it. So yeah, it was prominent. So I ghosted for some of my colleagues in the romance departments. I ghosted for other people, too. Don Heck once ghosted for me, once, when I hit an artist’s block. I couldn’t produce anything for about a week. I begged him to help me out, and he did a beautiful pencil job.

SPURGEON: Were you becoming aware of the community of cartoonists working in comic books at this time?

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. I was not as gregarious as I should have been. I was a little bit sheepish, a little bit shy. I was 19 years old when I started. I used to go up and wait in the waiting rooms, and listen to the other people talk who had more experience. I remember Davey Berg and Jack Abel and Gene Colan and guys like that, we were always there for somebody to throw us a three or four-page bone. It was like shaping up on the docks like a longshoreman, you went there hoping to get work and if you didn’t get work, you just went without income for a couple of weeks.

SPURGEON: When did you decide to stop ghosting?

ROMITA: I thought about getting work by myself almost immediately after I got to Governor’s Island. As soon as I got settled in, I went uptown in uniform, because I had a Class A pass. I presented myself to Stan Lee’s secretary, and said, “I’ve been working for Stan for a year and a half and he doesn’t know me.” And she came out with a script! Not only that, but she came out with a script and she expected me to ink it, too. That was the first story I ever inked for Stan Lee after penciling for a year and a half.

SPURGEON: I assume this one of the knock-out secretaries that Stan was famous for.

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. [Laughter.] A blonde. Oh, was she gorgeous. It used to stop my heart just to talk to her. The next time I went up I remember he had a beautiful brunette. He always had good-looking women there.

While I was in the Army, that was even when I did a short run on Captain America, in the mid-’50s, ’53. I was just getting out of the Army just as the Korean war came to an end. I got out of the army in July of ’53. I started doing Westerns at that time.

A Dream Come True

SPURGEON: Was doing Captain America a thrill for you, having admired Kirby?

ROMITA: It was a dream come true. All I did was frustrate myself because it was never good enough for me. It was hard for me to do it. I wanted it to look just like Kirby, and I ended up sort of having a mish-mosh between Kirby and Milton Caniff. I couldn’t help myself, because I thought like Milton Caniff even though I admire Kirby’s Captain America. So, I always felt responsible for the failure of that book. Stan told me it was a political decision. Captain America had hit some very rough periods there. Patriotic was a bad word, and the flag was a bad word in the middle 1950s. So, there was a backlash against Captain America. The other two titles, the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner which Everett came back to do continued for a year or two after Captain America was dropped. I always felt like a terrible failure. Stan always told me it had nothing to do with the artwork; he loved the artwork, but it was politically unpopular.

SPURGEON: Did you have a different perspective on what was good in the art form at this time? There were different artists working in different modes than when you were analyzing the field as a reader.

ROMITA: When you’re doing the work, you don’t have the time for reflection and theory. You’re just glad to get the pages out. And the quicker you get the pages out, the quicker you get the check and the next story. So, what happens is you go into this cycle, like a guinea pig on a wheel: You just keep running until they don’t have any more wheel for you.

This is an interesting thing I’ve discovered. Whenever I interview, people ask why I struggled so much, why I didn’t knock it out like everyone else. Part of it was because I felt like a salmon swimming upstream. I always felt like I was behind everyone else because I started late. Everybody seemed to have a head start on me. I admired people who were only a year older than me, like the Joe Kuberts and the Alex Toths of the world. They were blazing this beautiful trail, and I always felt like I was lagging way behind in the race. And I never felt adequate. It was a terrible affliction. I also felt like I was a style-less artist, a guy with no style, a generic illustrator. The guys who did the toothpaste ads, they were good artists, but I ended up having that generic toothpaste smile on all of my characters. I always felt inadequate because of that. I felt like I didn’t have enough personality. I felt like it was a failure of mine for not being an adult storyteller. So I suffered from feelings of inadequacy all through the 1950s. It was terrible.

SPURGEON: Did you have trouble meeting deadlines because of this?

ROMITA: Deadlines were always a problem for me. My natural bent was not to accept my first thought and to try to turn out a masterpiece every time. Actually, after my first story, I did a story with the guy I was ghosting for, for Famous Funnies. I think the first story I ever did was before Stan Lee gave us any work. I did a 12-page romance story for Famous Funnies. After I did the first page, I thought, “That’s it. I don’t think I can get another panel out.” I did 15 pages of a terrible romance story, and it was so bad that the editor up there — I always forget his name, damn it. He was a wonderful guy. He used to buy artwork from young artists even if he knew he wasn’t going to use it.

SPURGEON: This would be Steve Douglas?

ROMITA: Steve Douglas! I think he has a cherished place in heaven. He must have helped hundreds of us young artists out. He paid me like $200 for that story, and I think he knew he was never going to use it. He had a pile, maybe ten or 12 inches high, on his desk of artwork from young artists he was never going to use. And I still bless his memory, and I should remember his name. Steven Douglas, for God’s sake, Abraham Lincoln.

So I did that story, but I thought I would never live through it. I fell asleep at the drawing table like three or four times that week. It was terrible. The girls in that story looked like bony men. It was just awful. That was probably when I decided to learn how to draw women because I was so inadequate. I had drawn Westerns and war stories and science-fiction stories in my mind. I had done scribbles of my own characters, Terry and the Pirates type stuff. But I never did the women well. I forced myself to become a better artist of women.

I felt very inadequate. I felt like I was never learning. Something drove me. Even though I needed to make the money, I could not force myself to just knock the thing out. I tried to make each panel something new, which is crazy! You’re supposed to set up a formula. If you don’t set up a formula as a comic artist, you can’t make a living. You need to have a standard approach, where you fall back on your normal stuff, the stuff you’re good at. But to try and make an illustration in every panel that’s brilliant and new, that’s the way to kill yourself.

SPURGEON: It sounds like you had a certain amount of integrity as an artist.

ROMITA: Occasionally, there were guys, there were illustrators who said, “Pay me $10 a page, I’ll give you a $10 page. Give me a $100 a page, and I’ll give you a $100 page.” I always envied that. I couldn’t do that. If a guy gave me $5 a page, I would still do it as well as I could do it, to the detriment of my income and my sleep. It was something that drove me. I didn’t want to put my name on anything I wasn’t proud of. I was terrified of turning out something that was bad. I always had the feeling, even though I know that not many people read comics, although they were selling pretty well then, I had the feeling … I toyed with the idea of using a phony name for year. I don’t know what drove me to spend all those hours I should not have spent. At 23, I got married, and I’m raising a family, and I would still burn the midnight oil and work Saturdays and Sundays because I wanted the stuff better than I had originally envisioned it. So yeah, there was something that drove me against all economic forces. Very strange.

SPURGEON: Were there artists you learned tricks from to help you speed up?

ROMITA: It was even more direct. When I did love stories, I had a lot of Alex Toth love stories around me. When I did adventure stuff, I would have Caniff and Joe Kubert and Carmine Infantino. These were guys I thought were much older than me, and I find out later that they were only a year or two older than me. [Laughter.] They were so advanced in my mind, I was using them as a model. So yeah, definitely. I would be influenced and assisted by everybody who went before me.

SPURGEON: People sometimes forget how influential Toth was in determining a certain look for comics.

ROMITA: Actually, Toth led an entire new movement. When I got into comics in the late ’40s, and then in the early ’50s I went over to DC to do love stories, Toth had changed the whole approach to DC Comics. Up until then, it was a Dan Barry, polished, tight look. Toth loosened everybody up and got everybody wide awake. They all discovered Scorchy Smith. They discovered Sickles because Toth maybe had 300 dailies of Noel Sickles in a stack of Photostats. People were copying from that stack of Photostats, and handing them out to each other. The whole industry was using those Scorchy Smith dailies. And that’s when I found out that Caniff and Sickles had developed that style together. We all sprang from that. I think it lit a fire under the whole industry.

Joe Maneely

SPURGEON: Didn’t you famously spend a day learning tips from Joe Maneely?

ROMITA: Yeah. Stan sent me up. The first-time Stan discussed what my artwork would need — I brought in a second or third story, and Stan took a little time with it. And said, “You know what I’d like you to do,” because I was feeling my way as an inker, “I’m going to call up Joe Maneely. I’m going to tell him to put a day aside and have you go over to his studio.” He had a studio in Flushing, which was about 15-20 minutes away from where I lived in Queens. So, I went up there and spent about four or five hours, from noon to about four. He kept working and talking and just gabbing — he wasn’t doing any actual instruction, he was just showing me and talking generally. He was a genius. Absolute genius.

I learned more in those four hours than I did in ten years of doing comics. I may have learned more in that day than any other. He was absolutely the most unselfconscious, productive person. He was penciling a double-page spread or a full-page drawing — somebody said they weren’t doing double-page spreads, but it looked like a double-page spread to me — of a Western scene, with a stockade being protected by frontiersmen and a circle of Indians around the stockade firing at them. He did that whole thing while I was talking to him. He penciled it in the first hour or so. And then he started inking it, and it was almost half-finished by the time I left. It was like a revelation. Talk about formulas — he had his figures in these beautiful shapes, he had general shapes for arms and torsos and things like that. Then he would add features to the block of the head. Then he would finish to the end of the arms. And when he went to ink them, he turned them into the most lively, fresh drawings you ever saw in your life out of nowhere! Just with a basic foundation, a formula underneath. It was like a diagram he drew, and then he put flesh on it with the pen line. He started to do some brushwork to show me. The process was pencil it quickly, do the outline in pen, where you do the actual finished drawing, where you do the features and the eyes and the nose and everything, and the buckskin and the wood texture on the stockade. Then he would go over with a big #5 brush and do nice, big crisp accents.

I realized that this was the process that Jack Kirby and Joe Simon had used, and other people had used down through the years. It was the formula that I had referred to but I had never learned. I had struggled and penciled my drawings, labored over the pencils, and labored over the inks. I sometimes had to correct them. But he was doing them so crisply, so swiftly, it dazzled me. I went home and couldn’t wait to get to the drawing table. That one day was probably one of the most important days of my life.

SPURGEON: Was this early in your career?

ROMITA: I think I was still in the Army! It might have been ’51 or ’52.

SPURGEON: It’s been edifying for a lot of people to see Maneely’s reputation restored a bit the last few years.

ROMITA: I used to get mad when people forgot him. I used to substitute-teach for people like John Buscema at Visual Arts. I would get his class, and the first thing I would ask is, did they ever hear of Noel Sickles or Joe Maneely. I’d get blank stares, and it would drive me crazy. I’d say, “You know, if I taught this course on a regular basis, you’d have one day a week of just history,” just to learn where all this stuff came from. From Howard Pyle, the great illustrator at the turn of the century, then N.C. Wyeth, then Hal Foster, then Sickles and Caniff and Alex Raymond … Hal Foster was like the torchbearer. I would have to tell all of these people that if you don’t learn that, you’re not going to learn the process. You’re going to be learning from the newest artist, who probably has everything all botched up by now, instead of the original source. So, I definitely think that Maneely has been long overlooked. Have you ever heard the story that I’ve told at a lot of conventions, that if Maneely hadn’t died before he was 40, it might have been hard for the rest of us to get work? [Laughter.] Between Jack Kirby and Joe Maneely, Stan could have gotten his whole production done. [Laughter.]

SPURGEON: He got along very well with Stan.

ROMITA: He and Stan got along very well. He was like a self-starting engine; you didn’t have to give him anything! [Laughter.]

Simplicity

SPURGEON: When I look at your work from the ’50s, there’s a period where you used a lot of shading, a lot of shadow effects.

ROMITA: I don’t know what prompted that. The first time I did that, Stan went crazy, he loved it. I wish I’d never done it. It cost me a lot of money and sleep. He asked me to do something in a documentary style, about some poor preacher on the waterfront who was living on the edges of society. I did with a lot of shading, a lot of line technique. There were a lot of illustrators and a lot of comics artists using that technique. You needed to be very delicate, and comic books were not the place to be delicate, because the reproduction always made things blotchy. So I did the story this way, and Stan went crazy. I almost got myself lynched by my fellow artists because Stan asked them all to do it for a while. They wanted to kill me, because they said it’s costing us hours and hours to do that extra technique. [Laughter.] It was only a temporary thing, thank God. I’m glad I got out of it. Elaboration I think is the worst enemy of comics. I think simplicity is the direction. Unfortunately, years ago elaboration became the keyword instead of simplicity. I think Toth was righter than people like Neal Adams and [Todd] McFarlane. I think they put too much technique in their stuff, and the industry deserves simplicity and clean artwork. It reads better, and it’s more alive and spontaneous. As you know, one of the things hurting the industry now is that there’s too much technique and too much attention to the color and reproduction, and not enough attention to the freedom of the storytelling and the artwork. I bemoan that fact. I think that’s one of the things that’s hurt comics. I know the fans love it. It’s like the tastes of fans, in movies and comics, have caused more mayhem in the production of movies and comics, because fans don’t have good taste. Although I shouldn’t say that. [Spurgeon laughs.] Actually, I don’t mind. Quote me, because I don’t need the fans to buy my artwork anymore anyway. [Laughter.] I bemoan the fact that taste has gone out the window. Young fans love that technique stuff. And to me, that’s the worst thing that has happened to comics.

That’ll get me lynched, huh?

Two-Company Man

SPURGEON: The vast majority of your work was for just Marvel and DC.

ROMITA: It’s interesting. I was not one of the guys who jumped back and forth, like Gil Kane, or Jack Abel. They used to tell me, “Why don’t you do this? The companies respect you more when they know you got somebody else who wants you.” I was the kind of guy who, if I didn’t have to leave and I got comfortable, didn’t want to make any moves, even if it cost me money. I felt that comfort was more important than money. I needed to be comfortable; I did not want irritation, I did not want to deal with new people all the time. I got comfortable dealing with Stan. The only reason I left Stan in ’58 is because he shut the line down. I was forced to go, so I went to DC and only did love stories for about eight years, which almost put me in the booby hatch. I almost got out of comics because I thought I was burned out. It was so boring. It wore me out.

SPURGEON: Did you have any perspective on the anti-comics crusades?

ROMITA: I was in about ten years when that came to a head. I watched it, just because I thought my industry was going under. I used to tell my wife Virginia next year they won’t be any comics. In ’54, ’55, I thought it was all over. I was not too unhappy. I always thought that comics was a stepping stone to get me a little bit of money in the bank and to get me a little bit of proficiency in drawing, and then I would become an illustrator. And I almost had this subversive feeling that I wished comics would stop so I could get out there and do illustration.

SPURGEON: When I hear artists talk about comics as career in the 1950s, there seems a certain level of contempt for comics. Whereas it seems you had a healthy respect for the medium.

ROMITA: I never had contempt for comics, but I wasn’t always proud of being in comics. I used to tell people I was a commercial illustrator instead of a comics artist. You know the story about people who used to put a comic book inside a regular book so that people wouldn’t see them reading comics? I was the same way. I felt it was the stepchild of the commercial art field, and it was not something to be proud of. But sometime in the mid-’50s, just about the time when it looked like there wouldn’t be any comics, I started to think look at all the comic artists that were doing work I admired and I suddenly realized if I never got out of comics, if I never became a Saturday Evening Post illustrator, it wouldn’t be the end of the world as long as I do the best comics I can do. I decided to be at peace with comics, and try and be the best comic artist I can be. That absolutely relaxed me because up until then I felt like I was in it on a temporary basis. I never expected to be in comics. I never dreamed there would be a comic industry past 1958. I thought comics were finished.

SPURGEON: How did you learn about Stan Lee shutting down the Goodman line? There are stories that Stan let people know personally.

ROMITA: I had just ruled up a full Western book — I think it was Western Kid, I’m not sure and I had drawn maybe five or six pages when I got a call from Stan’s secretary, a beautiful brunette. [Laughter.] She told me that Stan was canceling the Western book, and to stop work on it and send in the pages. The fact that she asked me to send in the pages, I was assuming that Stan was going to pay me for the work I had done. But when I sent in the pages and nothing came, I was very hurt and very disappointed. In fact, I told Virginia, “If Stan Lee calls, tell him to go to hell.” [Laughter.]

SPURGEON: I assume he didn’t call.

ROMITA: He didn’t call me personally. With 20-30 artists working for him, it would have probably been a chore. The girl did say that Stan was closing all the books down. I was hurt for that reason, and for another reason: I found out that Dick Ayers and Don Heck were still getting work from him. I thought, “Gee, I thought I was one of his top guys. After seven years, he always said he could trust me with anything.” I thought that I’d be one of the last guys to go. The fact I was third or fourth on his list hurt me. That was my own insecurity. The truth of the matter is I was making $24 a page when Stan pulled the plug on me in ’58. I started out at $25 a page, and every time I went in with a story he gave me a raise. He’d tell the girl, “Give John Romita $2 more a page.” I was up to $44 a page. I was one of his prime guys. Starting in the beginning of ’57, every time I brought in a job I got a cut of $2 a page. Before you knew it, I was down to $24 a page. Virginia kept saying, “How far down are you going to go before you quit?” And I used to say, “Well you know, he may reverse it, and we may build up the page rate again.” I was always an optimist, and a little bit of a sucker. I should not have stood for all those cuts. When he pulled the plug on me, and I was so upset, a week later I was riding on Cloud Nine because I went over to DC and got $38 a page to do love stories. So I said, “Here’s Stan Lee, who cut my throat, turned out to be giving me a $14 raise.” I was so happy to be working at all, even the love stories didn’t dampen my ardor. I jumped in with both feet and, before long, I was making $45 a page from DC doing love stories.

Survey of the Field

SPURGEON: Do you have an opinion concerning the substance of the criticisms that were being made against comics in the 1950s that they were overly lurid, for example?

ROMITA: Well, I have to admit, a lot of comics companies were terrible. Even Stan. The first horror story I did we used to call them mystery stories, the first horror story I did for Stan, I think was a five-page story, the last panel was some villain holding up a decapitated head with blood dripping from its neck. I was very upset to do it. I did it as tastefully as I could, for a 22-year-old. I tried to do it tastefully. But I will admit that a lot of guys did not do tasteful stuff. And the EC books, as clever as they were and as talented as the artists were, were very, very gory. And very strange. And disturbing. I never read those books. I used to look through them, because I admired Wally Wood, Al Williamson, Joe Orlando — all of those guys were doing wonderful stuff. I admired them as artists, but I hated the stories. I did not like EC books. I never thought humor and blood went together. To me, satirizing horror stories was not fun. And they thought it was so clever. I always hated that.

I even will tell you that I did some semi-bondage covers for a small company. I did Western covers where a girl was tied to a chair, and some villain was nearby, and her clothes half torn away. And I knew they were bondage covers. I was just trying to make a living but I did not like that kind of stuff and a lot of that stuff was done terrible, ugly bondage stuff. I was not fooled. The comic industry I knew was a cheap, easy way to make a buck. I stayed at Stan Lee’s because I think Stan always had a feeling of entertainment before sleaze. Strange as some of the stuff in the ’50s was, he always had a certain amount of story in there, a certain amount of characterization, even when he was knocking those five-page stories out. There was a certain kind of personality in everything. So, I always felt that DC and Marvel or Timely was doing stuff a little bit better.

I also loved the Lev Gleason stuff from the ’40s when I was a kid. The crime comics were never as bloody as the horror, and the crime comics had such personality. That was because of [Charles] Biro, and some of his artists were wonderful, like George Tuska. As a kid, I loved them. I was sorry to see Biro go. Unfortunately, I don’t remember much of Biro’s stuff during the late ’40s when I was at school and doing Coca-Cola ads. I wish I had. I met Biro’s daughters last summer at San Diego. It was wonderful to meet them. I went over to them purposefully to tell them I thought Biro was a pioneer, and I couldn’t believe he hadn’t been more remembered before this. I wanted to tell them he wasn’t forgotten by people like me, who learned a lot from Biro just as a reader.

SPURGEON: You’ve said that one thing you enjoyed about Biro’s stuff was that he put a bit of his personality into his work.

ROMITA: He did. In fact, he was doing what Stan Lee has done for years. He was just doing it before. What Stan is doing now, Biro did when I was kid. He put personality into his Daredevil book, and into his little line of tough kids. Remember? I thought those were wonderful books. So, I didn’t think the comic industry as a whole should have been indicted, but there were some comic companies — you know the trashy ones — that were doing some terrible stuff. I was ashamed of that, and I was not proud to be in the industry then. But I always thought there was a redeeming quality in some of the comics, and that should have been salvaged. But I never expected it. I thought we were all going to go down the drain.

SPURGEON: What was Stan Lee like in the ’50s?

ROMITA: Stan was amazing. I will tell you, I’ve maybe worked for a half-dozen other editors. That’s not much of an experience. Ninety percent of my work has been done for Stan. Other editors have sometimes a taste problem, or a judgment problem. They don’t really know what’s good or what’s bad. Or if they know what they like, it’s not as good as it could be, because their taste is bad. I have had a lot of editors with bad taste, and very bad manner. I never worked for Bob Kanigher, but if I had, I would have thrown pages in his face and walked out. He was absolutely the most crude, meanest guy. He was out to make people feel bad. He tore into people in the bullpen as an editor. I never worked with him as an editor, although I collaborated with him on love stories. He was my writer on two of my series at DC. And we worked only as a team, but we never worked together. Thank God, he was never my editor. I always worked for an editor like Phyllis Reed, who was a wonderful editor.

But Stan Lee, compared to the other editors I worked for, was like an angel. A special being. First of all, he looked at your stuff, and he absorbed it. He was thoughtful, and he gave you a response. He told you, “This is very good. This is not so good — work on this.” I learned more every time I went in with Stan with a story, and he would take the time to critique it. That’s how I learned so much. I was feeling my way, and he was the best editor. On top of that, when he wrote my stuff, he almost invariably made the stuff more believable. In other words, I would have misgivings when I would turn in a story from a plot. There would be a 20-page story with no dialog, no captions. I would half believe it. In other words, I worked on it as well as I could, I would make it as airtight as I could, but I didn’t have a lot of faith in it. By the time he scripted it, and I read the script and his placement of the balloons, it looked as though every single panel was thought out carefully between two people. He was a magician. He took time to place balloons you would not believe. He would sometimes rearrange balloon placements three or four times. In other words, here was a guy who was working the clock three or four times. He was constantly turning out work. He would sometimes do a full story in an afternoon. Ten or 12 pages in the morning, ten or 12 pages in the afternoon. And he would take the time to rearrange the balloons because they weren’t aesthetic or they didn’t flow in readership. He was in a class by himself. No editor ever gave me the response and information that an artist needs that Stan did.

No matter what people say about Stan — and I used to grumble about him, too; he takes a lot of credit and all of that stuff — the truth of the matter is there is no better editor than Stan in comics history, and he was one of the best writers I ever worked with. I can’t believe writers could do much better. I’m sure Peter David and guys like that are on a par with him, and the newer writers are very good, but for me Stan Lee was in a class by himself.

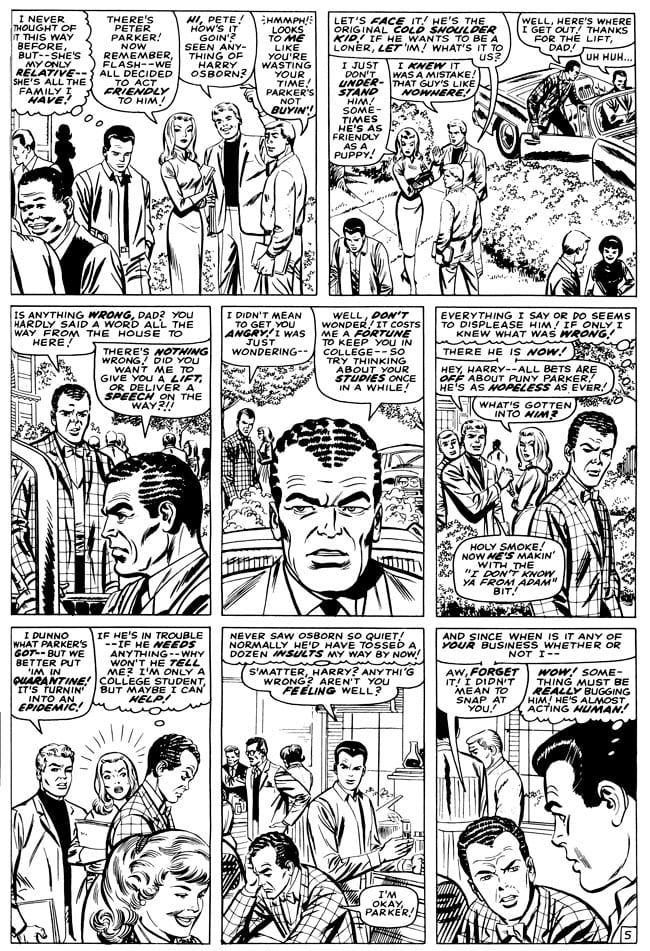

Romance is Hard Work

SPURGEON: Let me ask you about your stay on the romance books with DC comics, from 1957-’58 to 1965. You’ve said that the work wore on you after a while.

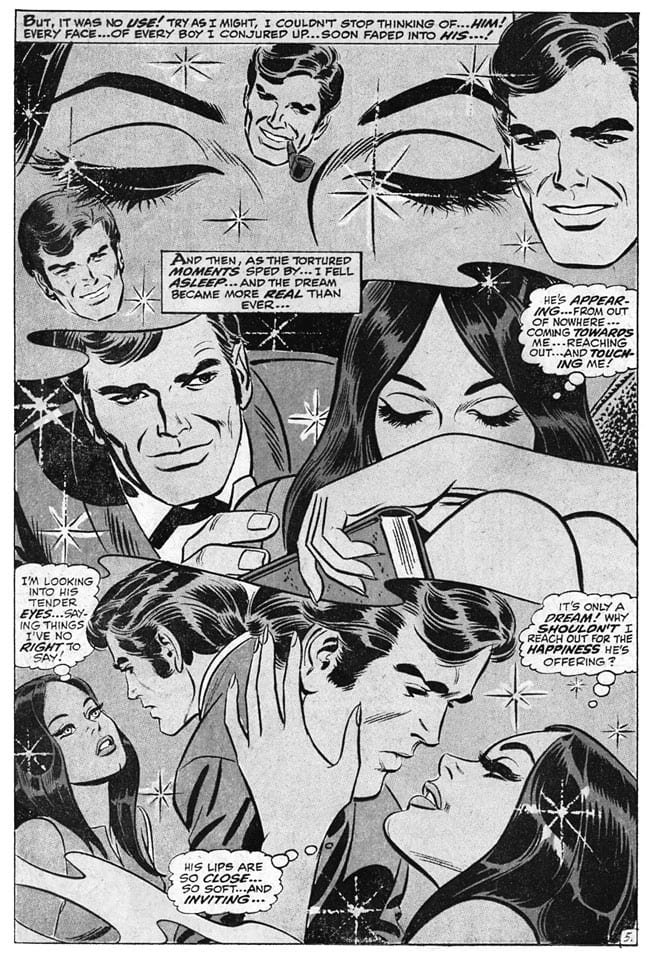

ROMITA: It wore me out because it was very hard. The truth of the matter is that nothing was happening in those stories. You would get 15 pages where a girl loved a guy, but he was aloof, and she would be heartbroken. He would smile at her, and she would be happy. Then he would go with another girl, and she would be crying. The same story for eight years. It drove me nuts. But what it did was it made me a better artist. I will tell you that if I were to take a comic company, if I had taken one in the ’60s, I would have had everyone trained in animation and in romance stories as well as adventure stuff because it forces you to make something out of nothing. There are certain gaps in stories where nothing is happening and the artist has the responsibility of making it visually entertaining. To make it move. The dynamics is the biggest challenge. Everybody is standing around, leaning on their elbows, their chin on their fists and smiling. The only thing I could do was to jazz it up with things like hair flowing, scarves flowing, the wind blowing leaves or curtains blowing. Whenever I had a chance to use water, I would use some nice wave techniques. Trees blowing in the wind. Romance books forced me to make entertainment where nothing is happening. I learned that partly from Alex Toth, because when he did his love stories, he had the most interesting twists and turns of bodies and heads. Tilting the head this way, that way, backwards, three-quarter back views — all of the tricks that a novice can muster you learn in romance or else. Otherwise, it’s deadly dull.

What happened was that after eight years it wore me out. I had the worst artist’s block. Don Heck came to my rescue, about the end of that eight-year run, in ’63 or ’64. If he hadn’t come to my rescue, I wouldn’t have been able to earn a penny that week. I absolutely sat there and could not produce a page of art for weeks and weeks. And I assumed that I was burned out. I had been working 15 years in the business. Seven for Stan, and eight for DC, and I assumed, “That’s it. I obviously can’t think of another panel, so I’m going to get out of the business.” I even went down to BVD and signed up to do storyboard. I backed out of that because Stan talked me out of it. He promised to match whatever money BVD was going to pay me.

SPURGEON: Is the romance period the first time in your career you did a lot of covers?

ROMITA: I was doing almost all the covers for the DC romance line for six, seven years. Phyllis Reed and I worked constantly on that stuff. What happened was, she had fallen into a great trick. She didn’t like some of the plots that writers were coming up with. So, she started to send them plots. And one of the ways she elicited plots was when we were doing cover drawings. Instead of doing a cover that represented a story that’s already been done, we did the cover first and then the story after. We would build a situation; she would choose a situation that we would draw. And she would build a storyline from the covers. Consequently, we would discuss it by phone. I had a couple of steady characters, an airline stewardess and a nurse. She would say, “I’d like to do a story about the nurse where’s she losing her confidence,” or something. We would incorporate it into the cover, and make it as dramatic as we can. And that would trigger her to send a plot to the writer. Kanigher would take the plotline from her, she probably gave him a two-paragraph synopsis and Kanigher took the ball from there.

I think there were six or seven titles, and I think I did most of the covers for about five or six years, with the added burden that these covers were going to lead to plots. She had come to trust me so much because my suggestions on plotlines were part of her arsenal. She counted on it. She recommended me to be the editor of the romance department when she decided to have a child and leave.

SPURGEON: Becoming an editor didn’t appeal to you?

ROMITA: I was tempted. Not because I wanted the work, because frankly I’ve dreaded the idea of going to work every day. I was tempted for two reasons. First, I thought if she wasn’t going to be the editor, God knows who’s going to be in there and would I get any work? So, I said, “Let me think about it.” The next time we talked, she said, “The only thing I got to tell you, John, is in case you haven’t realized it, if you take this job as the editor, you’re going to be losing your best artist.” That’s the problem. Then I knew I wasn’t cut out to be an office editor. I didn’t have any real training in writing and literature. I had artist’s education, I didn’t have a lot of English composition. So I had no background in writing. I would not have been qualified to correct other people’s writing. [Laughter.]

SPURGEON: Was DC itself a turnoff?

ROMITA: My memory of DC was, I used to go in and I would say hello to the bullpen when I was bringing in art work or bringing in pencils to be lettered. I’d met Sol Harrison and all the guys in the bullpen, but I always felt like an outsider there. For eight years, I would go in there and I always felt like an outsider. I was never embraced and brought into the clique. It was almost like they were very cliquish. They were very cold to their artists and writers. The editors had a very terrible reputation where they would play the artists against each other. Each editor wanted to see which guy’s work you do first, that kind of stuff. They were very brutal. Julie Schwartz, I never dealt with him. I would assume he wasn’t. But I wouldn’t be surprised if he was. The editors I dealt with were very cold-blooded and very, very harsh. Very quick to criticize and very slow to compliment. They would say, “This is crap.” That kind of stuff. Certainly, Kanigher used to scream out, “You call this a pretty girl? That’s a dumb, fat-looking girl here!” I never got that with Stan. I used to say that DC is like an obstacle course for an artist. You go in there, and all you get are obstacles. You don’t get any kind of help. I did feel that for years. I was very happy to get back to Marvel.

SPURGEON: Is that the reason you didn’t do any adventure work at DC?

ROMITA: No, the reason for that is they never asked me. And that broke my heart, too. I told Virginia, “Now that the romance department closed perhaps they’ll offer me something in the adventure department.” But I never got a call. I went in there. It was July, and a lot of them were on vacation. I was not very pushy, and not very confident, either. Even though I had had a brief chance to work on Flash Gordon with Dan Barry — I was going to do some fill-in work for him, and I thought, “Gee, if Dan Barry likes my stuff, this is good news.” But there was a newspaper strike right before I was going to start, and he couldn’t afford to pay for help, so I never did it. My confidence was not very good. I thought I was limited to romance and very antiseptic stuff, and that I couldn’t compete with the big boys. I assumed that’s why they didn’t call me. What happened is after I went to Stan in ’65 and inked a story, and during that time was when I expected to hear from DC’s editors. It took me a couple of weeks to ink a Don Heck Avengers and a Jack Kirby cover. In fact, I told Stan I just wanted to ink, because I thought I was burned out as a penciler. When I didn’t hear from DC, I felt terrible. I really felt bad. It was probably 50 percent my fault, because if I had gone up there and said, “Let me talk to everybody,” but I never did. I was too shy. I was too uncertain to do it. So, they must have figured, “If he doesn’t want to work, we won’t offer him any work.” I kept thinking, “Gee, why didn’t they call me?” As soon as I took on an assignment to do my first Daredevil story in ’65, they called me up, George Kashdan I think. They called me and offered me Metamorpho, because Ramona Fradon was leaving. And I said, “Gee, I wish you had called me last week, because I just agreed to do this for Stan, and I don’t want to go back on my word.” I think I probably could have made more money at DC, but I don’t know what kept me from doing it. I could have just told Stan, “Stan, you know, I got too good an offer from DC, I’m going to go over there.” But for some reason, I decided to stay with Stan.

SPURGEON: Metamorpho wasn’t exactly a prestige assignment, either.

ROMITA: If it was Batman or Superman, I would have jumped. [Laughter.] I hope that I would have had the sense.

Analyzing Marvel

SPURGEON: Were you aware of what Marvel was doing at the time?

ROMITA: That’s the funny thing. I was aware that Stan was making noise. They talked about Stan at DC quite a bit. They used to discuss why Stan was starting to sell books, and why his reputation was growing, but I didn’t have the sense to go and buy some books to see what was happening. I never saw a Spider-Man book until I went back to Marvel. I never saw a Fantastic Four. It was my own stupidity. Truthfully, the only books I was looking at were books I could pick up at DC and read for free, because I wouldn’t spend money for the books. I was so cheap. I was not keeping up with the comics industry. The only thing I used to pick up were guys like Alex Toth and Joe Kubert, and, of course, the romance books. I heard things were happening there, but I wasn’t aware of exactly what. I never saw one to judge it. When DC’s romance department was shut down, they had such an inventory to use, so DC front office said, “The hell with this, you’re not paying for new artwork until you use up all of those.” So, they shut down the romance department. I had no work, so I went back to Stan. I wouldn’t have gone back if DC had offered me anything decent; even a second-line adventure thing, I probably would have stayed there. I was very proud to be there. I always thought that DC was the Cadillac of the industry.

SPURGEON: I think most people thought that.

ROMITA: They did. It was. It was very much prestigious. In a way, I was sort of snobbish about it. It was one of the things that kept me there, even though I was bored to tears. Stan used to call me all the time, in ’62 and ’63, saying, “Come back.” I always had the excuse that he was only paying $25 a page and I was making $45. So, I’d tell him, “Stan, I can’t take a cut.” I was proud to stay there, but I think because Stan guaranteed me to match my salary at [the advertising agency] BBD&O, and I wouldn’t have gotten any guarantee at DC, I think that was the reason I stayed with Stan.

SPURGEON: Did he promise to give you a certain amount of work, or did he promise that regardless of the work you did he was going to pay you a set amount?

ROMITA: I don’t know if he could have backed it up. I told him, “I can’t work at home anymore.” He said, “We’ve got a drawing table here at Marvel, you can come in any time you want, you can work all hours.” It was such a good deal. I said, “My problem is I can’t discipline myself.” Because I had that blockage, I told him I couldn’t guarantee I would work every week, and that’s why I didn’t want to pencil anymore. And he said, “Tell you what. If you can’t do any work for a week, you’ll still get paid.” Now frankly, I don’t think he could have backed that up. [Laughter.] I was gullible enough to believe him. I think Martin Goodman would have told both of us to get out if he had tried to pull that one. That’s one of the things he conned me with. He told me if I couldn’t turn out a page, I’d still get paid.

SPURGEON: You must have found your penciling ability, though, because pretty soon you were on Daredevil.

ROMITA: That’s interesting. When I did the first Daredevil story, the first three pages were very dull. As much as I had tried to do dynamics, I froze up a little bit. Jack Kirby broke down my first two stories on Daredevil. It was a very rough pacing and size guide, scribbles and outlines, to show what to put in a panel and how to pace it. So those first 40 pages of Daredevil, #12 and #13, were guide lined by Jack Kirby. They weren’t pencil drawings, they were sort of silhouettes and initials — DD for Daredevil, Matt Murdock was MM, that kind of thing. That’s what triggered me into getting Stan’s way of penciling. For a while, while I was learning, I forgot my drawing block. It was never easy, though. I will tell you, I worked 50 years in comics, and I don’t think I ever had an easy week. I don’t know why anybody would stay in a business that twists your guts every single day, but I did for some reason. I kept telling Virginia, “Soon as I get an ulcer, I’m quitting this business.” I never got an ulcer, and that’s the reason why I stayed in the business. [Laughter.] It was never fun for me. It was never easy. Guys like Jack Kirby and John Buscema could knock out a story and never bat an eyelash. With me, it was a chore from the minute I started.

SPURGEON: You were at this point immersed in the new Marvel. With your analytical mind for art, did you figure out what they were doing that was making them successful?

ROMITA: Not only that, but that’s the reason I started to be called art director. I not only learned the theory of everything, but I also learned how to indoctrinate people in Stan Lee’s way. When Stan was too busy, and there was an artist that needed some kind of instruction, because I was in the office, Stan would say, “Listen, go in and talk to John Romita. He knows exactly what I like.” And sure enough, I ended up being his substitute voice. When a young artist came in, I would give him all of Stan’s catchphrases and whole spiel.

SPURGEON: What would you tell the young artists who came to talk to you?

ROMITA: Stan’s approach was basically this. Think silent movies. In other words, all your characters have to act overtly and very clearly. You don’t do anything mildly. You don’t have somebody with his arm bent, pointing a finger. You have him thrust his arm out in space. The Jack Kirby way. Every sinew of a body is involved even if you’re saying “Go down this street two blocks and make a right on the next corner,” you look like you’re pointing at Armageddon coming. If a man slams on a desk, you don’t make it just where a guy’s fist is on the desk resting. You have him pound the desk and everything on the desk pops up like an earthquake. You never have anybody who’s saying something, especially shouting, with his mouth closed. There was a whole generation of comics artists where everybody’s mouths were closed, and everybody’s eyes were half-lidded. And one of the things I learned immediately from Stan was if somebody was talking, have his mouth open. If he’s shouting, have his mouth wide open. Show his teeth. And that was Jack Kirby, too. Some of it was Jack Kirby’s natural approach. Some of it was Stan Lee’s acting school; the way he used to act out all the plots. The stories he’s famous for. He used to jump up on the couch, he used to jump on the desk, he would run around the office, he would strangle himself, he would use voices.

He was saying your characters had to act, clearly, loudly and dynamically. So, what I just told you, I used to embellish and tell people, “Don’t do anything mild, don’t settle for the first thing you think of. If you can make it better, make it better. Everything has to be exciting.”

SPURGEON: Was there a transitional period for you to get used to the Marvel Method, working from rough plots rather than scripts?

ROMITA: It was very hard. First of all, I said I couldn’t do it. I told them they were out of their mind. I had it hard enough trying to make it work, where my natural ability, if the writer would ask for a certain thing and it didn’t fit my natural ability, I used to go crazy. I had to figure out a way out of it. If I had nothing to start with — I had artist’s block! Imagine what kind of artist’s block I would have when I had nothing except the bare-bones outline of a story. The first story was very hard for me. Very, very hard for me. I had to have Jack Kirby’s help.

What happened was that after a while I started to realize this was a visual medium that had been done words first and pictures second for 35 years. And I said, “You know something? This now can become the visual medium it really is supposed to be.” The people in silent movies were ingenious, because they didn’t have dialog. They had written words, but it used to be a set of interruptions. Movie geniuses erupted in Hollywood because they were working in silent film. Movies went downhill when sound came in because they no longer had to rely on their genius of the visual medium. It became a verbal medium, and it hurt Hollywood. Comics was a visual medium that was never used visually, except by geniuses like Jack Kirby and Alex Toth. They did comics visually from instinct. But people like me, when a writer asks me something, I was bound and shackled by the writer’s concept. What happens is, if you’re not shackled by that, if the range and width of your thinking is limited, you can only do certain things. But suddenly, when you have the whole thing to choose from, when you have to set up a sequence because you have to know what’s happening in panels one and two before you decide on the big spread in panel three, you have to think visually. When I found out not only wasn’t it hard; it was liberating. I think the comics boom is a direct result of the accidental thing that Stan Lee did just to save time, plotting stories quickly because he couldn’t get the scripts done. That led to the biggest comic boom in history. And I think it was strictly Stan Lee’s accidental, little change.

Yes, it was very hard at first, but I think it kept me interested longer than I would have been.

Steve Ditko

SPURGEON: How long was your stay on Daredevil?

ROMITA: Only about six or seven issues. It broke my heart, because I really loved Daredevil. I was really sorry to have to leave it. I did it because I was a good soldier. Stan needed help on Spider-Man, and I said, “OK, I’ll do it.” For a long time, I thought Ditko might come back and I could go back to Daredevil.

SPURGEON: Was there some sense in the office that Steve Ditko might quit before he did? From what I read, I get the feeling that everyone thought Spider-Man was a gig that could potentially open up.

ROMITA: I had heard that they were having trouble. What happened was they were disagreeing on the plots violently. Stan told him, “All right, you can plot the stories.” Then there was a problem because Stan would change the thrusts of the stories because his sensibilities made him change them. Ditko was a very conservative thinker. If he had a story about rioting students, he would make them horrible rioting students. They were breaking the law and they should be dealt with. Stan would give them motivation, and instead of the black and white of it he would give you both sides of the story. Ditko would do a whole story of a riot on campus, Stan would change the thrust of the story, and that would lead to changes in expressions and everything. Stan always did that. He did that with Jack, he did that with me. Many times, I would have one thought in my drawings, and he would turn it into something else. And that was the proof of the pudding of what a great writer and editor he was. He was impressed with artwork, but he wouldn’t hesitate to change the artwork if he thought the story could be better.

That’s a great editor.

SPURGEON: Did you know Ditko personally?

ROMITA: I only met him a few times. I have about ten horrible regrets, and one of them was that I didn’t make the time. When you’re in the office for years and years, you always feel that the next time we can get together. I was busy most of the time. Ditko would be walking down alone, or somebody else would be talking to him, Marie Severin or somebody, and I’d think, “I gotta go out and talk to him.” And I never did make the time. We used to say hello, and we shook hands a few times, but I never made the time to talk to him. I regret that terribly.

SPURGEON: He had a really unique artistic sensibility, particularly given the time.

ROMITA: I consider him one of the true creators in the business.

SPURGEON: Is it true that it took you a little while to warm up to his work?

ROMITA: That’s one of those things that got printed that I regretted. Because it came off sounding terrible. One of the first things in an interview way back in the ’70s was I said that when I first looked at the first three or four issues, I thought they were overly simple and too crude. But that’s the part that came through on the interview. They didn’t give the full context, where I said that by the time I got into the 20s in the run of Spider-Man, learning the ropes on Spider-Man — I got the whole run of Spider-Man from Stan to look through. The first few issues I felt he was really knocking them out. They were not the same Ditko I had seen doing jungle stories and horror stories where he was a polished brush-man doing gutsy, juicy stuff with a lot of shadows. In Spider-Man he was doing very quick line jobs with a lot of small panels. What I said was I didn’t understand why the book was such a success, because I thought the book was rather crude and the characters were rather simplistic. But what I added was that it was amazing how he developed by the time he was in the 20s and the 30s, the books were coming alive and they were powerful and I admired them. Right from his middle 30s, #33, #34, #35, were some of the best comics ever done. That’s where I launched myself from. In fact, I tried to ghost it.

I don’t know if he read that interview or didn’t read it. He never complained, but I always cringed when I thought, “Oh my God, he must have felt so hurt when he read that I would say his stuff was too crude.” I didn’t mean it that way.

SPURGEON: I always thought it was pretty remarkable that Ditko was able to be that idiosyncratic that late in the medium’s development. His style is still really striking.

ROMITA: That’s one of the reasons I earmark him as a creator, because he’s one of the few guys — there are like a dozen guys like that. The George Tuskas, the Jack Kirbys, even Don Hecks. Don Heck got put down a lot. He was a guy like Colan, like Ditko, there were a few guys who did what I would call a complete world on paper. If you looked at one panel of Jack Kirby, you knew where you were. You were in Jack Kirbyland. And when you were in Ditkoland, you knew where you were. The reason I called myself a generic illustrator because my stuff, I could make you believe you were in anybody’s land. [Laughter.] I could do Ditko, I could do Jack Kirby, I could do Don Heck, I could do Caniff. I could even do Colan. I used to fake Colan’s stuff. So, the thing is whatever those guys do have an integrity, a completeness about it; they created an entire world. My world reflects the real world. I do real buildings; I don’t do them like Jack Kirby, I do them like the buildings look to me. That’s why I consider myself an illustrator. I’m doing real people. I try to make them distinctive, and give them personality. When I first started, I was doing such generic people. Everybody had the same nose, everybody had the same smile, everybody had the same dimple in their chin. I realized I was doing horrible stereotypes. I started using movie actors. Whenever I’d do a war story, I’d say, “All right. This sergeant is going to look like Burt Lancaster. The private is going to look like Kirk Douglas.” When I did Westerns, the secondary characters with the big beard and the crooked teeth, the Gabby Hayes thing? I got all my characters from movie stars. That’s how I got some personality in my stuff. I couldn’t create a Romitaworld, although later on people tell me they recognize my stuff right away. That was a shock to me when I heard that.

SPURGEON: Although you don’t seem to have a high opinion of the distinct nature of your own work, I think people believe you put a really strong graphic thumbprint on Spider-Man, even the definitive one.

ROMITA: It’s interesting, because I started out trying to ghost Ditko. It didn’t work. I realize now in retrospect I didn’t do it, but I thought I was doing a complete ghosting of Ditko, line for line.

SPURGEON: Did you feel the book was Ditko’s?

ROMITA: I thought the responsibility of a second artist on a book was to make the reader think it was seamless transition. I felt obliged to make the book — if the book is a three-year success story and building, I felt that we didn’t need change on this, it was a success! I’ll do the same thing. If I were to take over Dick Tracy, would I give Dick Tracy a straight nose or would I keep the nose he had? If I were doing Little Orphan Annie, I wouldn’t start doing pupils in her eyes. Seventy years later, and Annie’s still got no pupils in the daily comics. I was raised in that generation where an artist was obliged to ghost the work that he picked up from the previous artist. I tried like crazy. I worked with a thin pen, I even did a story with a rapidograph. The Rhino story I did with a rapidograph just to do it like Ditko, to get that thin pen line and big brush line. The only reason I didn’t get closer to Ditko was because I was physically unable, just like I had failed in the ’50s to do a convincing Kirby take-off. Then I realized in retrospect I guess I had enough of a personality that I couldn’t do other people that well. I could simulate Kirby. I did three or four issues of Fantastic Four in exactly the Kirby style. I did romance books in other people’s styles. I always felt like I was a pinch hitter, I was a bullpen guy. The other guys, the Ditkos of the world, they were the starting pitchers. The guys to emulate. That was my take.

The Look

SPURGEON: There had to be some point on Spider-Man that you realized you were the second-day’s starting pitcher rather than the relief guy.

ROMITA: It started to dawn on me. After about a year, I realized he wasn’t coming back. It started to become mine, because I started to use more brush. By the time, I was doing the Vietnam story, I was doing it more like Caniff. It had become my stuff. Stan kept complaining that I was making Peter Parker too good-looking and too well-groomed. Even though I tried, I could not make Ditko’s Peter Parker, that sort of stammering nerd. I couldn’t do it. For some reason, my heroes had to be good-looking, had to be square-shouldered. Stan finally gave it up, and said “The hell with it. Do it your own way.” He liked the rest of my approach. He accepted some of my limitations.

SPURGEON: I think it’s a big part of your run’s appeal. It’s a very glamorous book in a sense.

ROMITA: Historians now look back on it and say, “It was a maturing period, and Peter Parker matured.” From this stammering young teenager to an 18, 19-year-old, finally maturing, getting better looking and more confident. They took it as contrived and schemed by Stan Lee and myself. The truth of the matter is that it just happened. Like I told you, when Stan wrote the stuff, it was different than what I envisioned. Most of this stuff took on a different personality than I had envisioned by the time it happened. We would go through sequences where we would plan nothing, absolutely nothing, even how the story was going to end. Sometimes we would do a five or six-issue epic, and it would grow and build and we had no idea where we were going. Looking back at it now, it looks like every single step was planned. Like the quest for the Rosetta Stone, the tablet, that became an epic that traveled through about like four different villains. It looked like we planned it from the beginning. We had no idea there was going to be a Silvermane at the end of that storyline. It was accidental.

SPURGEON: One notable difference in your version of Spider-Man as compared to Ditko’s is the prevalence of the female character. By this time, you had become very comfortable drawing women.

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. Actually, I think that’s what saved my skin on the book.

SPURGEON: I can’t think of any comic to that time which had mixed these romance elements into the superhero material so explicitly, although in general mixing genres was a real strength of the Marvel line.

ROMITA: It was a very interesting thing. That was a lucky break for me. Instead of rejecting the fact that the pretty girls were starting to dominate the story for a while, instead of saying “What the hell is going on?” — like when I was a kid watching Westerns; I did not want to see those pictures where the cowboy kissed the girl at the end; I’d rather see him kiss his horse or something — we were able to bring the readers along for a ride. As we were changing our approach and as things were changing, the readers were changing, too.

A lot of readers have told me at conventions that they grew up with Peter Parker. My own son says that. He just did an interview for the DVD of Spider-Man where he says he felt like he grew up with Peter Parker. He felt like he was a brother. He was a brother he didn’t have to worry getting hit by. [Laughter.] And if my own son fell for that, can you imagine what the readers did? They tell me now, at conventions, that they learned how to react to things, how to think, how to behave from some of the comics the same way I learned how to react and behave from movies. We were sort of like the old movies from the ’40s that I weaned myself in. The comics took place in the ’50s and the ’60s.

Cinema

SPURGEON: A lot has been written how the original comic-book artists were taken with movies, but it occurs to me that your generation may have been more immersed in films than they were. Were you a fan of the movies as a kid?

ROMITA: My mother used to have to come to the theater and search for me. I could sit through three or four showings of films. I’m talking when I was 9 or 10 years old. She’d drop me off at the movies and then she’d come pick me up and if I wasn’t there she’d have to come in and find me.

SPURGEON: Were you as analytical with films as you were with comics?

ROMITA: Sure. The same perceptive reaction I had to comic books, I had to movies. For a 10 or 11 year old, I was very aware. I would know if there was a very dark secret, a social secret. There was a rape in an early movie I saw. The girl is married to an older man, and I remember feeling and understanding everything that was going on. And I was about 12 years old! I was very aware of every emotion. The storytelling in movies absolutely gripped me. I could not leave the movie theater. I had to be dragged out.

SPURGEON: Did you make distinctions between filmmakers, did you have favorites?

ROMITA: Oh, yeah. Capra, Ford, Hitchcock — I was aware of them all. I’m talking about watching Hitchcock when I was ten or 12 years old and understanding it. I had an affinity for film and for Milton Caniff. Caniff freely admitted that movies affected everything he did. I could see Katherine Hepburn and all the other movie actors in his characters.

SPURGEON: How do you think film informed your artwork and that of your immediate peers?