New media and retro internet aesthetics being portrayed, explored, and satirized in comics has become a recurring theme in self-published and indie publications. This article is about this artistic tendency to put onto paper that which is typically found on screens, and what examples of such tendencies tell us about the world they were inspired by.

Network Ideology and Techno Utopias

One thing a comics fan can appreciate about the medium is that it is not everywhere. While great works deserve to be read, and we all wish for talented artists and writers to make a living, the underdog status of comics is often celebrated. In contrast to comics’ relative obscurity, the internet is omnipresent and increasingly omniscient. As Shoshana Zuboff’s recent book, Surveillance Capitalism, has outlined, our world has become dominated by internet economics, which is invasive and often functions without our consent.

I will use the terms “the internet” and “new media aesthetics” interchangeably in this article. While there is a distinction between the internet and objects which let you access it, most users’ daily experiences of new media devices don’t inspire such recognition, and one’s ability to be “offline” while using a new media device in a world dominated by data, streaming, and cloud services is severely limited.

For generation X- and Y-ers, it may seem boringly obvious to point out that the contemporary tools of our work and social lives are intrinsically linked to a network ideology which distributes itself via infrastructure that is prima facie immaterial. The internet, both the idea and the look of it, has colonized our notions about the purpose of a proliferated computer culture. Inspired by Marshall McLuhan's prediction in the early 1960s that humankind’s media would result in a harmonious "Global Village,” the type of network ideology as espoused by Facebook has persuaded us to believe that we must always be connected. But at what cost?

Commercial sci-fi and superhero comics have traditionally been unsubtle when implying the view that technology solves problems rather than creates them. An example: the character Oracle, who is featured in various Batman comics, is persistently surrounded by screens. As her name implies, her access to technology grants her the ability to peer from above in order to see more than those on the ground. She is the human embodiment of the surveillance element of new media technology, and with this purchased power she assists the heroes. Meanwhile, Star Trek is perhaps the most obvious demonstration of a dreamed-up world in which technology is the basis for a new utopian, multi-species society. The word “basis” in this case is more than just a metaphor; the characters in Star Trek walk and breathe within the USS Enterprise, an example of technological advancement.

Anti-Utopian Field Reports

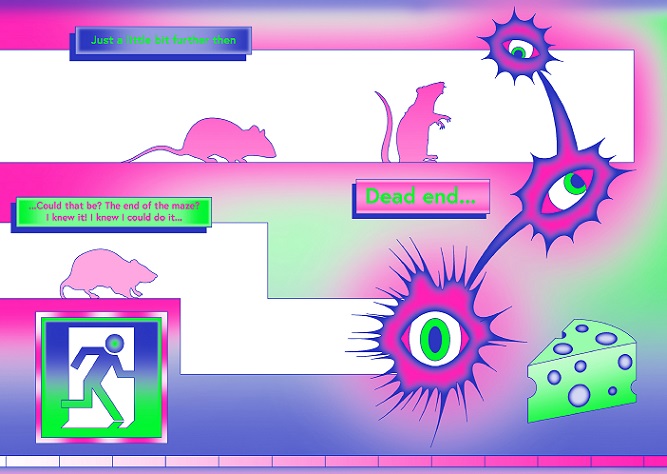

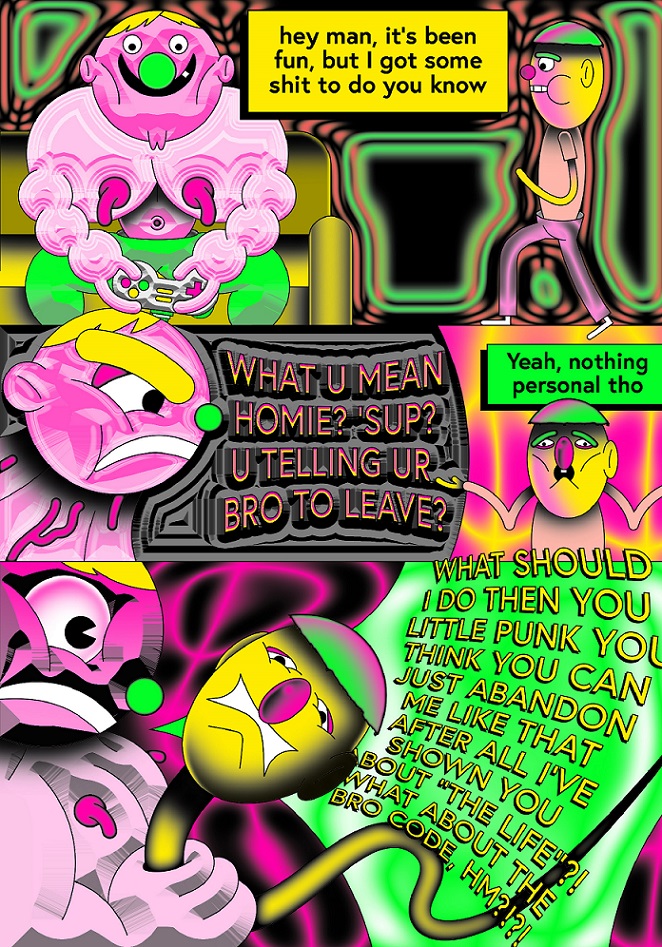

Sander Ettema’s Friends in Many Places is the most explicitly negative report from the trenches of a life immersed in digitality. It is a psychedelic journey told through the perspective of a narrator overwhelmed by a constant explosion of notifications and distractions that new media offers us. Its five acts consist of a stream of consciousness interaction with anxiety-inducing antagonists who continuously apply pressure in order to ensure constant productivity. Friends does not seek the illusion of realism or to display the lines of an artist’s hand. Instead, it brashly adopts stock shapes and “word art” fonts.

In the introduction, Ettema writes that producing Friends was a coping mechanism with which he could use to wrestle with his own anxieties and stresses caused by overexposure to social media and online content. As I wrote about in my review of the book for Your Chicken Enemy, I see the physical limitations of the paper the comic is printed on as being used here as a way to restrict the intense and perplexing enormity of the internet. Once extracted from its root digital file and printed onto a limited plane, it is as if the endless potential of the digital has been captured and restrained, made human again by its application to the tactile and innately impermanent materiality of the book. This is an illusion, of course. The new media aesthetic is autonomous to representations of itself, but Friends provides a very striking account of why and how that illusion, that moment of control, becomes a necessary beast to capture.

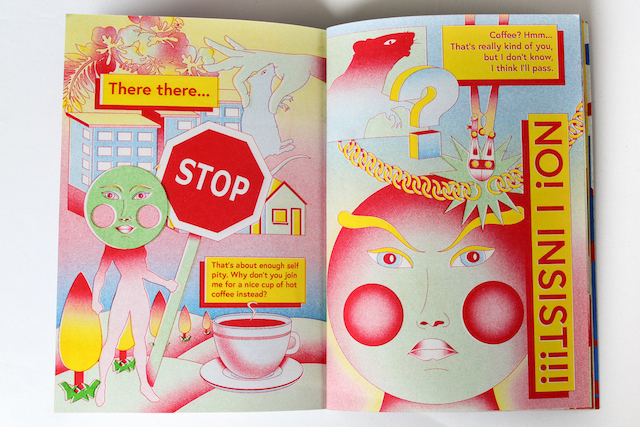

Like Friends, Marlene Krause’s Computer Class is printed on a Risograph machine. Riso is a printing process that, in the context of comics about the pervasiveness of digital aesthetics, is interesting because with its margins for mechanical and programmatic error, it is a method that subverts the notion of endless and perfect reproducibility. Perfect reproducibility has been strongly associated with digital techniques since Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which was something of a dystopian vision of a future without “originals.” The perfection of the repeatable replicas of websites or images or texts found online is impossible if you’re using a Riso machine to print, a topic I have delved into elsewhere for The Comics Journal, in an article titled “Setting an Antitype.”

Like Friends, Marlene Krause’s Computer Class is printed on a Risograph machine. Riso is a printing process that, in the context of comics about the pervasiveness of digital aesthetics, is interesting because with its margins for mechanical and programmatic error, it is a method that subverts the notion of endless and perfect reproducibility. Perfect reproducibility has been strongly associated with digital techniques since Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which was something of a dystopian vision of a future without “originals.” The perfection of the repeatable replicas of websites or images or texts found online is impossible if you’re using a Riso machine to print, a topic I have delved into elsewhere for The Comics Journal, in an article titled “Setting an Antitype.”

The sleeves of both books comment upon their contents: Friends has a shiny, silver-ink cover that mimics the faux platinum casings of electronic devices, while Computer Class has a transparent plastic cover that when looked at recreates the “black mirror” effect of screens. On the covered cover of Computer Class, you see your reflection in the reflection of someone else, and yet no one is actually in the picture. There are just two facsimiles, themselves reproductions reliant on reflective mediums.

Krause’s is a fantastical story inspired by her time volunteering at a web skills class at a community school. In the book, an elderly student of such a class, Eulalia, while struggling with the assigned tasks, is interrupted by a unicorn who appears from within her computer and encourages her to act on her impulses. One such impulse is to retort to a particularly unkind peer by whacking him on the head with her walking stick and then storming out of the class. While Friends and the next book I will discuss point towards a sense that the internet is totalizing, Class seems to offer a way out, as Eulalia literally leaves the room. Her worldview has not been built by the internet and its environments, and so her world has the potential to continue even as she steps away from gaining skills that are essentialized today.

Krause’s is a fantastical story inspired by her time volunteering at a web skills class at a community school. In the book, an elderly student of such a class, Eulalia, while struggling with the assigned tasks, is interrupted by a unicorn who appears from within her computer and encourages her to act on her impulses. One such impulse is to retort to a particularly unkind peer by whacking him on the head with her walking stick and then storming out of the class. While Friends and the next book I will discuss point towards a sense that the internet is totalizing, Class seems to offer a way out, as Eulalia literally leaves the room. Her worldview has not been built by the internet and its environments, and so her world has the potential to continue even as she steps away from gaining skills that are essentialized today.

BSKskater191, the protagonist of George Wylesol’s Internet Crusader, probably cannot imagine a world without the internet. Unlike Friends, Crusader doesn’t offer the reader a distinction between character and narrator or between diegesis and an online “world.” Via only BSKskater191’s desktop activity do we follow the story of the devil attempting to enter BSKskater191’s world, one dominated by the blocky and cartoonish sights of late 1990s graphics, through a virus-generated computer game. In Crusader, Lucifer, a character who famously fell to earth, arises via digital infrastructure. The dualism of above and below suits a description of the internet, too, which relies on both orbiting satellites and cables buried underground to function.

The Internet as Comics Practice

These three works share an interest in a retro version of digital aesthetics. They suggest a melancholic nostalgia, remembering a time when the internet seemed communal and simplistic. While mobile and touch screen technology is the current zeitgeist amongst consumers, these books portray a look associated with times when desktops were more common. These comics are retro thanks to their focus on desktops, and the fact that their artists are taking inspiration from just-out-of-date aesthetics and experiences. All three artists grapple with such remembered aesthetic experiences through the comics medium in order to come to terms with the recent past. They are anti-utopian histories about how the internet has come to be considered nowadays. In Friends, it is a feeling of overstimulation and a loss of agency; Class portrays the rebellion of walking away from technology; in Internet Crusader, network technologies are a method for classical evils returning.

Comics are particularly suited to depicting internet aesthetics. This is because the internet and comics are cousins in a familial cultural practice. Thierry Groensteen’s great insight, in his 2007 book The System of Comics, was to define comics as being primarily about the organization of space. As a practice dedicated to the division and exploitation of spatial relationships, “comics” could be seen as a genre in a category which does not yet have a name. This category is one which acts as an umbrella term under which we can consider the ramifications of the spatial organization of content, with examples ranging from billboards in New York City’s Times Square, the arrangement of paintings in a gallery, and the sequence of panels upon a page. The arrangement of content on a screen fits into this category, also. For the time being, let’s call all these practices examples of making comics.

When engaging with comics, there is not only the two-dimensional relationships to consider, such between the content on the page or on the wall. There are also the three-dimensional ones, predominantly the ones between reader and work. Digital interfaces have reformed many relationships, not only through social media and internet speak (which, perhaps, never really improves from the limited acronyms depicted in Internet Crusader), but because it has transformed our physical relationships to each other. We are wedded to being captivated by portable spectacles; we look down more often than we look up. Public sites, everything from public transportation to university buildings to cafés, are graded as to just how good their WiFi signals are. Even as life becomes unaffordable (financially, environmentally), in a state of collective isolationism, a state empowered by our devices, we may not notice such decrepitude.

Capitalism and Control

Comics depicting the internet can do so almost better than any other medium because comics shares two of the internet’s most defining features: multimodality and the management of space. We expect a combination of images and text in both mediums. The primary difference is that when we close a comic, we have determined the limits of our relationship with it, at least in the immediate and physical sense. There is no such exit strategy for the internet.

Zuboff’s Surveillance Capitalism details the economic impulses both behind and generated by the totalizing power of digital infrastructures and network ideology. The age of surveillance capitalism transforms the human into both the consumer of products and the product itself. Our data is harvested, our interests are predicted, and messages are tailored for us, even when our devices look “off.” Rather than us learning to determine how to be critical of all ideas, we are bred to expect ideas which already suit us. That constant drive to get your attention and to tell you what you should be hearing is the big, scary monster behind the unnerving world of Friends in Many Places.

By taking control of the aesthetics of the everyday and ubiquitous, the artists behind the comics I have discussed perform a dérive that subdues and subverts that which has been centralized, monopolized, and which exploits us. When we put down Internet Crusader, we relieve ourselves of the pressures of recognition and stimuli, much like BSKskater191 as he turns off the computer. But soon after, we will notice our proximity to the screens of other objects. In the fantasy world of Computer Class, Eulalia can recognize her hallucination of a unicorn for what it is, to take control, and leave the room. But in our actual world, is there any escape?