Celebrity cameos aren’t new to comic books. Both Stephen Colbert and President Obama appeared alongside Spider-Man, and Eminem got a two-issues series with the Punisher. Orson Welles helped Superman foil a Martian invasion and John F. Kennedy helped the Man of Steel keep his secret identity.

While working on Hidden Hemingway, my book about the writer's hometown archives, I fell into a deep rabbit hole: Ernest Hemingway appearances in comics. I found him battling fascists alongside Wolverine, playing cards with Harlan Ellison and guiding souls through purgatory in The Life After.

He’s appeared alongside Captain Marvel, Cerebus, Donald Duck, Lobo—even a Jazz Age Creeper. Hemingway casts a long shadow in literature, which extends into comic books. It’s really only in comics, however, where the Nobel Prize-winner gets treated with equal parts reverence, curiosity and parody.

But as author Tim O’Brien (The Things They Carried) has pointed it, there is no one Ernest Hemingway. In fact, comic books provide a more nuanced view of Hemingway than other forms of pop culture (see Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris).

In the 40-plus appearances I found across five languages (English, French, German, Spanish and Italian), Hemingway is often the hyper-masculine legend of Papa: bearded, boozed-up and ready to throw a punch. Just as often, comic book creators see past the bravado, to the sensitive artist looking for validation.

Here, in part one of a multi-part series: we explore Hemingway homages, appearances and doppelgangers in comics, from the divine to the ridiculous.

Tabula

Hemingway’s depiction as a comic character came early, in his senior yearbook, the Tabula, published by Oak Park and River Forest High School in 1917.

On page 138, in a comic titled “Some things We’ll Miss,” Hemingway appears under the subhead “Ernie’s Diving Form.” In the drawing, Hemingway stands awkwardly—with stubbly legs and hair tucked under a swimming cap —atop diving board. On the sidelines, his classmates rib him, Atta boy cupid!”

Another comic titled “Our Ideas of Heaven” features a newspaper sports page that reads “Hemingway Stars / Wins Plunge / and / Breaks End of Tank.” In parentheses under the illustration, a caption says “All this is true fame.”

Another comic titled “Our Ideas of Heaven” features a newspaper sports page that reads “Hemingway Stars / Wins Plunge / and / Breaks End of Tank.” In parentheses under the illustration, a caption says “All this is true fame.”

Hemingway’s own idea of heaven was very different when he described it to F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1925: “To me heaven would be a big bull ring with me holding two barrera seats and a trout stream outside that no one else was allowed to fish in and two lovely houses in the town; one where I would have my wife and children and be monogamous and love them truly and well and the other where I would have my nine beautiful mistresses on 9 different floors…”

Captain Marvel Adventures #110 (July 1950)

Hemingway’s first appearance in mainstream comics was a bit underwhelming. In fact, you have to squint to see him. As Captain Marvel and President Harry Truman tour the Half-Century Fair of 1950, Hemingway is one of the luminaries who populates a panel of cultural leaders. Hemingway is in the upper left-hand corner, accompanied by contemporaries such as Walter Winchell, Albert Einstein, Bing Crosby, Jackie Robinson and Louis B. Mayer. This was one of the few appearances published in his lifetime.

Coogy (1953)

This is the first of several Hemingway parody comics to appear in Coogy, Irving “Irv” Spector’s “Pogo”-inspired strip syndicated by the New York Herald-Tribune.

The strip had a brief run from 1951 to 1954, and Spector became better known for “funny animal comics,” and as an animator, notably on The Jetsons and The Flintstones. He also logged writing credits on How the Grinch Stole Christmas and Pink Panther cartoons.

This Sunday strip, “Across the Old Man and Into the Sea,” parodies two Hemingway novels (The Old Man and the Sea, and Across the River and Into the Trees). In the story, Mo (a bear) is mistaken for a marlin and lashed to the side of an overzealous fisherman’s dry docked boat. Ultimately, Mo gets rescued by his grandson (Coogy) and a friend, as the manic fisherman is left to dream about a successful catch.

(Special thanks to Ger Apeldoorn for directing me to this piece).

Vidas Illustres: Ernest Hemingway (1964)

What this 1964 Mexican comic book, Illustrious Lives, from gets wrong in fact, it makes up for in passion. Thirty-two pages of adoring, biography-bending passion that starts with the legend and work backwards (the most harmless example: Hemingway grows a beard at age 18 and never shaves it).

Particularly interesting: The final page of Hemingway’s bloodless suicide, where he’s discovered not by his wife Mary, but a young man who says, “Pronto! Un Medico!” The caption translates, roughly, to: “It is believed that his death was an accident that happened as he cleaned his shotgun.”

Our Army at War #234 (July 1971)

Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Dos Passos appear in a backup story titled “Mercy Brigade” in this Sgt. Rock-led book. In the eight-page story, a (historically inaccurate) blond Ernie rescues hospital patrons during a bombing raid, providing cover with a table he carries on his back, saying “Don’t despair! Old Ernie’s here!” He also foils an espionage plot and inadvertently kills the knife-wielding villain with a single punch.

“I-I’ve killed man, I killed a man,” he says, before his friends divert him back to the battle at hand.

At the end of the story, writer-illustrator Ric Estrada provides more context, stating: “This was a highly fictionalized account of three young men who served in the ambulance corps during World War I…who went on to become famous author: Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Jon Dos Passos.”

How highly fictionalized? Fitzgerald never left the States during WWI. (Maybe Estrada should have included Walt Disney, who served with the Red Cross in France.)

Adventure of Uncle Scrooge Treasure #3: The Trip to Key West (Der Ausflug nach Key West) (1984)

Papa gets Disney-fied in this tale of Donald Duck and family searching for treasure in Key West as a hurricane looms off the Florida coast.

Papa gets Disney-fied in this tale of Donald Duck and family searching for treasure in Key West as a hurricane looms off the Florida coast.

I saw a few warped panels from this comic framed on the walls of Hemingway’s house in Key West. The word balloons were in German, and I couldn’t find a version in English. I was stumped until Klaus Strzyz, a former editor and translator for Ehapa Verlag (the publisher of Disney comics in Germany), pointed me to this 1984 comic book.

The story was written by Adolf Kabatek, then chief editor of Ehapa Verlag. Strzyz believes that the issue was illustrated by Marco Rota, the art director of Disney Italy, in the style of Carl Barks. However, a Disney comics database maintained by Inducks identifies Miquel Pujol as the artist. An English-language version was never produced.

In this panel, Papa chats with a friend outside of Sloppy Joe’s Bar in 1935, as the town braces for the hurricane. It’s worth noting that the real Hemingway weathered a hurricane that same year, which inspired his piece “Who Murdered the Vets?”--his first-hand account of the storm, published in New Masses.

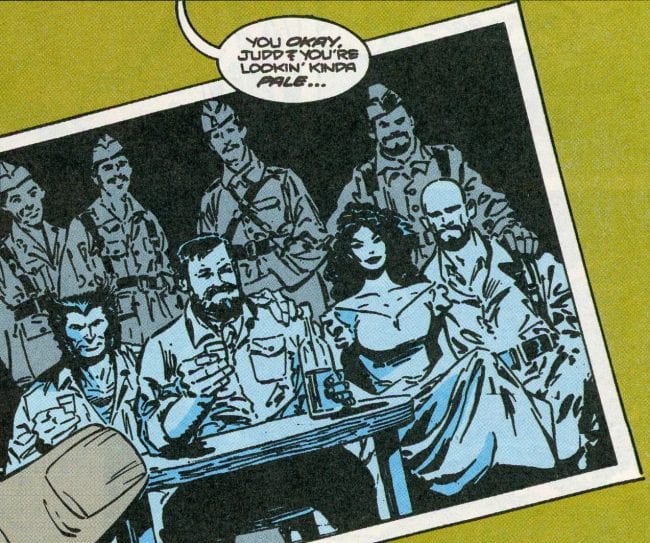

Wolverine #35-37 (1991)

When a time vortex takes Wolverine back to the Spanish Civil War, he encounters Hemingway at a bullfight, and promptly takes a swig from the author’s wine bottle. Heroic Hemingway acts as a guide to the out-of-time Wolverine and fellow Canadian superhero Puck.

When a time vortex takes Wolverine back to the Spanish Civil War, he encounters Hemingway at a bullfight, and promptly takes a swig from the author’s wine bottle. Heroic Hemingway acts as a guide to the out-of-time Wolverine and fellow Canadian superhero Puck.

Papa, however, is a secondary character in this three-issue arc, barely appearing in the same panels with Wolverine until the very last frame.

George Orwell also appears in this story under his real name, Eric Arthur Blair, in a story inspired by military historian Antony Beevor’s The Spanish Civil War. “I always liked Hemingway,” says Wolverine writer Larry Hama told me. “Wish I could write as pared down as him, but that requires real bravery.”

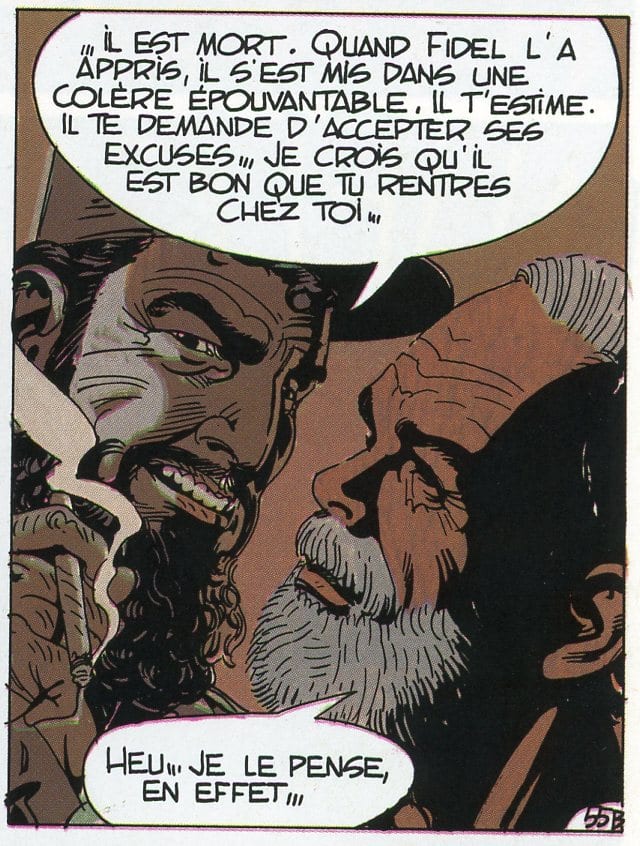

Hemingway: Muerte de un Leopardo (1993)

Hemingway is the focus of a revenge plot that spans decades in Marc Males and Jean Dufaux’s Hemingway: Death of a Leopard. The story is broken into flashbacks in 1930s Africa and 1959’s Cuba, where the author encounters the beautiful but complicated Anjelica, the daughter of two friends who died in Africa.

Anjelica blames Hemingway for her parents’ deaths, and then seduces him over dinner. “Writing for me will always be a good way of exorcising the past,” Hemingway says in the story. Eventually, Castro’s regime intervenes as the conspiracy to kill Hemingway comes to a dramatic conclusion.

(Thanks to Plume Beuchat and Gaelle Ramet of the University of Lausanne for their translation help.)

Speciale Nathan Never #4, “Fantasmi a Venezia” (“Ghosts in Venice”) 1994

When the canals of Venice start to lose water and the wife a friend goes missing, Nathan Never is sent to investigate.

When the canals of Venice start to lose water and the wife a friend goes missing, Nathan Never is sent to investigate.

Part Blade Runner, part Sam Spade, this popular Italian comic book blends elements of sci-fi with film noir. In this story, Never, a detective from the Alfa Agency, encounters Hemingway while drinking at an outdoor café. Once Papa sits down, he tells Never about Venice and dispenses advice on everything from drinking vodka to aging.

“If you haven’t lived, getting old is a nightmare,” Hemingway says. “Life is something extraordinary, it should be lived. You should try to experience all the emotions.”

The story takes a turn for the surreal with Nick Adams (Hemingway’s literary alter-ego) shows up as a former “great traveler” who now lives in Venice. Adams and Papa reminisce about places that don’t exist anymore. Expanding the narrative frame, Never begins deconstructing his own life: “If I was a character in a novel, I would think that the novel wasn’t written by one person, but by multiple authors who didn’t speak to one another beforehand.”

Hemingway responds: “It’s always like this in life. There’s no single author. Otherwise, imagine how boring life would be.”

Eventually aliens and spaceships explain the water’s disappearance from Venice, but who cares—the story has Hemingway.

(Thanks to Alessandra Garzoni of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, for her translations.)

Jesus Christ: In the Name of the Gun (2008)

Eric Peterson’ hyper-violent satire casts Hemingway in buddy cop genre, in which a vengeful, sandal-wearing Jesus of Nazareth is his partner. Here, the ninja-like Hemingway travels through time, assassinating history’s biggest mass murderers with the Son of God.

Begun as a web comic, the series embraces a strong moral core, punk rock ethos, Hunter S. Thompson’s gonzo zaniness.

“I’ve got more photos of Hemingway and Thompson hanging in my house than I do of my parents,” Peterson says, who admits that Hemingway’s depiction might be “borderline disrespectful for the writer that I love so much.”

In the third book of the series, Peterson says that he “really wanted to hone in on the fact that Ernest is a man chased by and chasing the idea of his own strength.”

He adds: “The author holds a very special place in my heart. I get a bit miffed that maybe the ‘legend’ of Hemingway holds a place in the mainstream consciousness more than the work itself. But, I think that’s just a part of his legacy. Same goes for Thompson.”

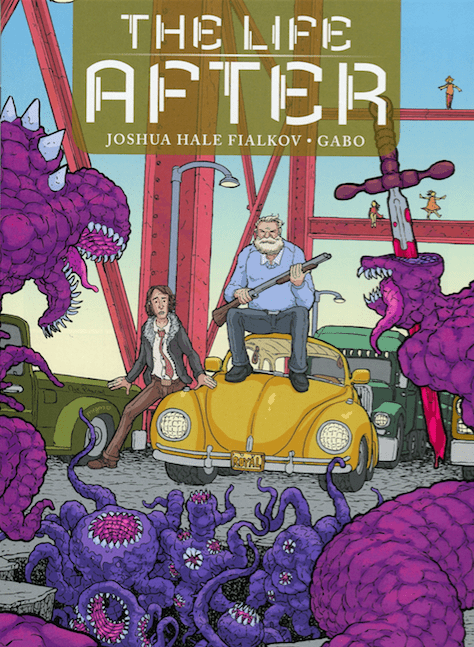

The Life After (2014) and Exodus: The Life After (2016), both limited series

When office worker Jude wakes up to discover that his sterile, repetitive life actually is Purgatory, he teams up with Hemingway to rebel against the celestial system.

According to creator Joshua Hale Fialkov, Hemingway was a relatively late addition to his series. “The Afterlife for Suicides is the most mediocre day of your life, lived out ad infinitum. So, who committed suicide but never lived a truly mediocre day? We landed on Hemingway,” says Fialkov.

In the book, Hemingway is Jude’s sidekick, the shotgun-wielding heavy who also manages to have a ménage-a-trois with a pair of sexy demonesses—in what is strangely one of the more tender episodes in the book.

“Part of the fun is that so much of his bravado and swagger was clearly exaggerated,” says Fialkov. “When you read his rough draft notes in any of his novels, the confident, ass-kicking man’s man is usually missing. That degree of insecurity that’s just bubbling under the surface is what makes him human, and a great foil for our protagonist.”

For artist Gabo (aka Gabriel Bautista), this was the second time his depicted Hemingway; the first was in the gleefully blasphemous Jesus Christ: In the Name of the Gun.

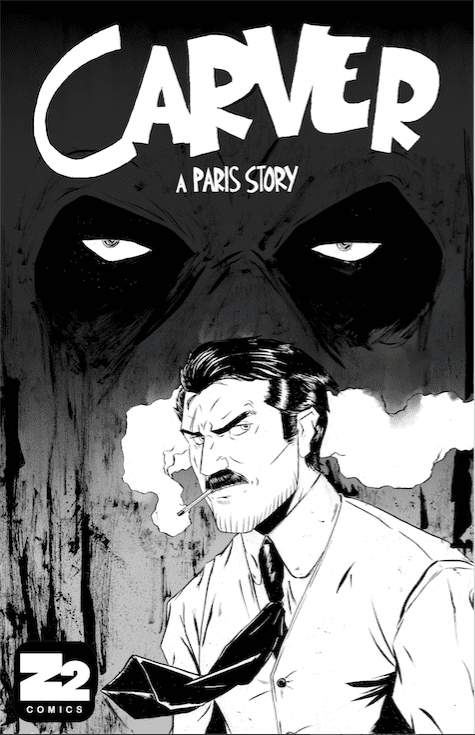

Carver #1-5 (2015-2016)

Chris Hunt’s hardboiled, two-fisted hero looks and dresses like Hemingway in the 1920s—and that’s no accident. Part homage to Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese series, part mash-up of Hemingway and Indiana Jones, Carver is a way for Hunt to deconstruct male archetypes.

“I believed there was some truth to the archetype in some way, and I wanted to find a way to introduce something that was recognizable,” says Hunt, who wrote and illustrated the five-issue, creator-owned series for Z2 Comics.

Hunt is a native of Idaho; he says the “specter of Hemingway paints over things here.” The specter makes it into his work, where artist-turned-soldier-turned-adventurer Francis Carver tries to unravel a kidnapping plot in 1923 Paris.

If you look closely, you can find F. Scott Fitzgerald talking to a sailor whom Hunt refers to as his “Bootleg Corto Maltese.” Paul Pope, Hunt’s friend and mentor, also provides some backup stories and covers for the series.

Superman / Wonder Woman #13 (2015)

Ponder this: In DC Comics’ New 52 Universe, Superman uses Hemingway’s typewriter, which was a birthday gift from Bruce Wayne, aka Batman. When Wonder Woman teases him for using such an “ancient relic,” as Superman explains that “sometimes the sound of the keys hitting the paper helps me compose my thoughts better.”

“I can type fast, but I can’t write fast,” he says.

“I liked the idea of Batman/Bruce Wayne giving his friend Superman/Clark Kent a Hemingway typewriter due, of course, to Clark's secret identity being a kick-ass reporter,” says writer Peter Tomasi. “In my mind’s eye, I imagined it was the typewriter that Hemingway wrote his Spanish Civil War dispatches on - a period in history I had a deep interest in due to a relative who served in the Lincoln Brigade.”

If you know of a Hemingway appearance we didn't feature, please email: info [at] hiddenhemingway.com.