The next time someone asks, “What comic strip would you most like to see reprinted?” your answer can no longer be “Shary Flenniken’s Trots and Bonnie” New York Review Comics has taken care of that.

The next time someone asks, “What comic strip would you most like to see reprinted?” your answer can no longer be “Shary Flenniken’s Trots and Bonnie” New York Review Comics has taken care of that.

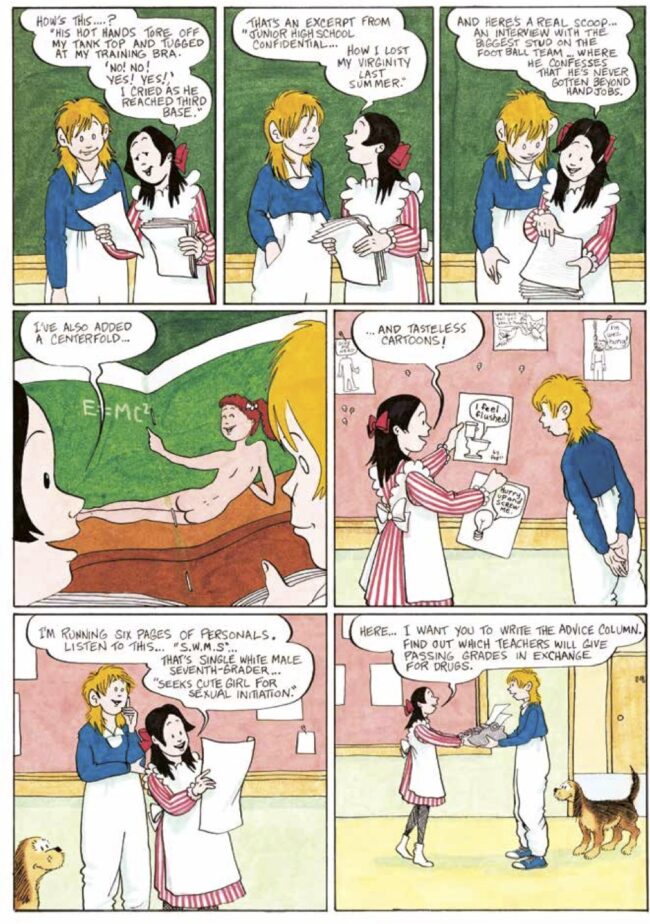

With transgressive art no longer, as cultural critic Laura Kipnis recently noted, hailed as a preferred way to “remake sclerotic structures and dismantle ruling class hegemony” but, instead, shunned, stifled and damned with, she goes on, “the transgressed... the protagonists of the moment; the offended people who are very upset by things” (Her italics), you might think this not the best time for a book in which a 13-year-old girl (or girls) have unapologetic sexual intercourse, fellate strangers, cavort nude before middle-aged male neighbors (in order to sell Girl Scout cookies), recite poetry written upon several dozen feet of paper unscrolled from their vagina (as part of a talent show), perform enthusiastically in the making of X-rated videos (to raise funds to purchase a pony), castrate a classmate (during a botched vasectomy), and electrocute a younger child (for raping a kitty).

But NYRC – God bless it – has defied the zeitgeist with a handsome, sturdy, nine-by-eleven-inch, 151-page (twenty-five in full color) collection of eighty-seven strips and stories (four-panels to six-pages in length), dated 1972 to 1991. They come buttressed by a gushy introduction from New Yorker cartoonist Emily Flake, an interview of Flenniken by the book’s editor Norman Hathaway, and an informative, often provocative paragraph or two about each assault on decency by the artist herself.

If you don’t already know, Bonnie is the taller, more prominently featured of the two thirteen-year-olds who dominate the action. She has strawberry blonde, cropped-to-collar-length hair, and seems never to have changed out of her white slacks and blue top – except for bed, the beach or frontal nudity – in her near-two-decades before the public eye. Trots is not the second jeune fille but Bonnie’s spaniel-mix mutt, of about knee-(Bonnie’s) height and indeterminate but steady age. He can talk, though he usually limits his conversation to final panels where he delivers pointed, humorous – Ba-boom – summative remarks. He also writes erotica – both in book form for human consumption and, through urination on walls and fences, for canine. (Are you laughing yet?) Pepsi, the other nymphet, who wears dresses and ties ribbons in her hair, is – in matters of carnality and politics – significantly more radical than Bonnie, who is continually, if some times astonishingly, left having to keep up.

The creator of these early-adolescent libertines was a 22- through- 41-year-old, dark-haired, blue-eyed, kiddingly self-described “shiksa Goddess” to a pair of Jewish husbands, who had been writing and drawing since she was a child. An admiral’s daughter, Flenniken had shared his postings around the world, before running away from her Seattle home upon graduating high school in 1968. After stops in Vermont, Key Largo, and upstate New York, she returned for commercial art school. By then a committed anti-war activist, she went to work for Sabot, an underground newspaper, which sent her as part of a team to put out a mimeographed daily at the nearby Sky River Rock Festival, at which she connected with the cartoonists who would become – Drum roll – The Air Pirates.

Named for a band of evil-doers who had bedeviled Mickey Mouse, the Pirates were the brainchild of Dan O’Neill, whose “Odd Bodkins” was the first – probably only – pro-drug, anti-Vietnam comic strip syndicated to major American dailies. After its cancellation, O’Neill decided to form a San Francisco-based comix-collective, whose contribution to the cultural revolution would be the destruction of Walt Disney. [For how that worked out, see my own The Pirates and the Mouse (2003).[1]] From these times and events, “Trots and Bonnie” emerged. The first several strips, including the never-to-be-forgotten-but-lamentably-excluded-from-this-collection episode in which Trots pleasures Bonnie orally,[2] appeared in comics put out by individual Pirates, Gary Hallgren, Bobby London, and Ted Richards. In November 1972, it debuted in the National Lampoon, where it ran exclusively thereafter. The Lampoon’s editorial directive was “Don’t do anything you can do in a straight comic.”

And Flenniken didn’t.

II.

writing is the art of... imposing oneself upon other people, of saying

listen to me, see it my way, change your mind.

Joan Didion.

one of my basic agendas in life is trying to save people from one thing or another...

Shary Flenniken

The major thing about which Flenniken wanted minds changed was sex. And the aspect which she most hoped to save people from was their ignorance about it. “(S)ecrecy about sex,” she told Robert Boyd, in 1991[3], “has done... incredible damage to people’s lives.” Given those beliefs – and Flenniken’s recognition that “Being inappropriate is one of my major life themes” – it logically followed that the frolics I reported at the beginning this piece would have become the life-savers she tossed the drowning, sort of like “One plus one equals two – and occasionally a threesome,” despite what the church or state would prefer you believe.

Aside from one early story, “The General’s Daughter” (1972), which cracked wise about American imperialism, racism and war crimes, Trots and Bonnie stuck pretty close to Flenniken’s backyard – and even “Daughter” took place down the block. Abortion, child abuse, cocaine, conspicuous consumption, eating disorders, family therapy, pap smears, penis size, pelvic exams, the Pill, plastic surgery, prophylactics, rape. self-defense. sexual harassment, slasher films, and S.T.D. all matters that could have crossed consciousness-raising groups she attended with her peers, played out through the pen-and-ink mind and bodies of her girls.

But Flenniken had not wrapped herself in a flag at which there would be reflexive salutes. The Lampoon, when she gained entry, was, with the major exception of the late take-no-shit Anne Beatts, pretty much a male preserve. (The editors, Beatts told Lampoon historian, Josh Karp, “thought women were a different species, like horses.”) Office honchos initially doubted women could even be funny; and the magazine’s core demographic, 18-to-25-year-old guys, numbered few among it, one imagines, whose courting codes would instill confidence if carried out by candidates for public office today. Flenniken wanted to widen the eyes of these readers to what the world was like for women. She wanted from them, she said, “empathy.” She needed to keep her editors backing at the same time she challenged their customers. “Frustration, anger and resentment were my muses,” she told Hathaway, but, along with guts and smarts, lightness and delicacy, – a sometimes deeply dark – humor was her tool.

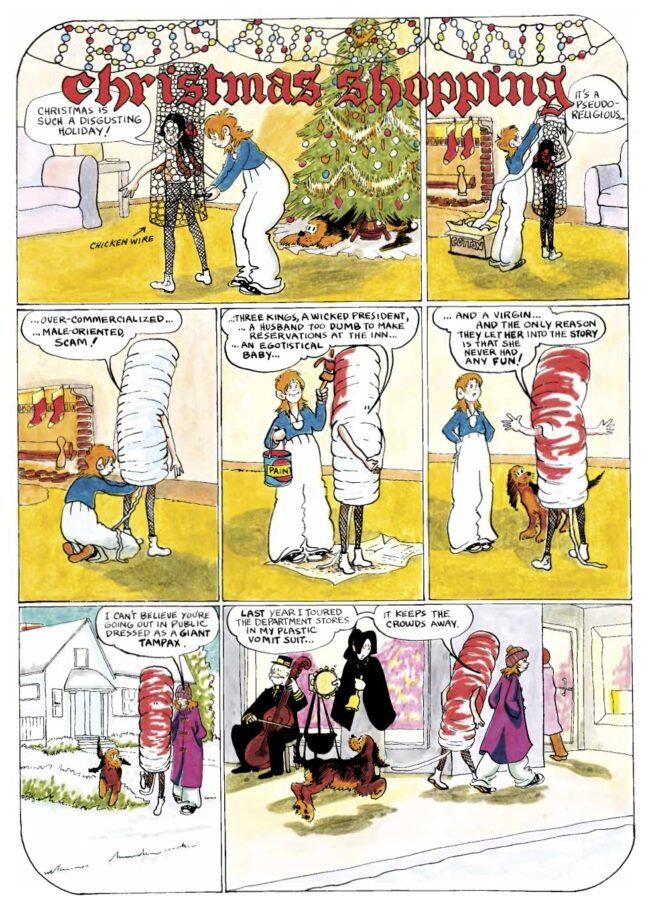

A basic rule of the underground frontier, where Flenniken had won her spurs, had been, “If there is a taboo, break it.” So no one should have been surprised when she sent Pepsi Christmas shopping, while costumed – in color – as a bloody Tampax, in order to keep the crowds away. You could say, “That is shocking!” Or “Vulgar!” Or “Tuasteless!” You also could say, “Well, yeah, that is something women have to put up with that men don’t.” You could recognize, “Yeah, damn, some men are put off – kept away – by women’s periods.” You could ask yourself, “What are they/we scared of?”

Yet Flenniken’s pies-to-the-face subject matter came delivered by a hand seemingly sleeved in old lace. While her characters’ conversations may be contemporary enough to encompass “tumorous lymph nodes,” and “trickle-down economics,” not to mention pubic hair trims, her art has a reassuring old-timey feel. “Heartland Country” is where the former Air Pirate/ current “Hagar the Horrible” artist, Gary Hallgren, situates Flenniken’s art. “Just a way of saying the homey pen and ink stylings... from comics past.” Flenniken, herself, cites H.T. Webster, who came to prominence in the 1920s, as her primary influence. Her drawings have that earlier era’s fine lines, its classic solid blacks balancing vacant whites. (Hence, Bonnie’s white lower extremities and dark chest.) There is, points out Michel Chouquette, the editor who steered Flenniken to the Lampoon, a small-town Gasoline Alley (launched 1918) feel to the environs in which her of-the-moment action occurs. Even the kid with dog trope dates back to Buster Brown/Tige (1902), Little Orphan Annie/Sandy (1924) and Little Annie Rooney/Zero (1927) – with the pooch’s linguistic skills extending beyond “Arf” no more recent a development than Barnaby/Gorgon (1942).

As the feminist historian/scholar/former cartoonist Trina Robbins says of Flenniken, “That gal can draw!” Flenniken eschewed the stripped-down, post-Peanuts school of near emojis to dare human recognizability. And she does not go for cartooning’s easy yucks. Her characters come with normal shoe sizes and small snouts. She conveys emotions and personalities with the slightest tweak of an eye (a dot) or mouth (a dash) – even Trots’s. Her details – a steering wheel, a sofa – anchor one to a “real” world, leaving the goings-on within it to transport readers to a land beyond their comfortable everyday. The verbal component to the panels is more significant than the pictorial, but the pictures consistently delight. As the eye takes them in, one smiles, then giggles, before being overtaken by sputters and spleen.

As a special treat, courtesy of Flenniken’s bubbling visual virtuosity, check the “Trots and Bonnie” titles above each strip, and see if you can spot one that duplicates another. The lettering varies in size and style and background adornment, reflecting a mind that is imaginative, wide-ranging, – and disciplined enough to keep track of where it has gone before. Flenniken did not have to do this. I doubt a single reader – well, maybe one or two – kept track, month by month, of what she was doing. I find it to be a tribute to her dedication to herself as an artist that she carried it on.

III.

Flenniken had a full set of artistic chops. She had courage and intelligence and wit. She had studied the past and was tapped into the present. She created characters who commanded attention and affection and she placed them in situations that made readers laugh and think, And then they disappeared.

And despite entreaties to Flenniken to bring them back, they stayed gone.

It was not like she had renounced her former beliefs. She had not retreated into a nunnery or ashram. Bonnie had not been stabbed fatally in the back with an ice pick like Fritz the Cat. Trots had not succumbed to shock and cold like Farley. They had simply been erased by the murk of business and the vespers of fate. The Lampoon had been acquired by new owners, who, in the brutal banalities of corporate-speak, wanted “to move in a different direction.” At the same time, following the death of her mother, Flenniken had returned to Seatlle, an ill husband in tow. She freelanced and edited and graphic designed. She worked on screenplays and in animation. She was anthologized and translated. She did “whatever came in on the phone.” She taught; she lectured; she counseled. She returned to college for her BA and won awards from cartoonists and the Seattle police. She worked five years in a hardware store. (“I got a lot of satisfaction working in a hardware store.”) When her husband developed Alzheimer’s, she became his primary care-giver, accepting the wonders and grief of that experience.

No matter how deeply Trots and Bonnie and Pepsi may have lodged in the hearts and minds of others, for their creator they were but one piece in a whole. “I love my craft,” Flenniken says. “I love everything about it. But I never focused on a career as much as men I knew did. I was more focused on living a life and learning new things.”

Here the gang is again though, as bad – and as adorable – as they ever were.