Viktor Hachmang did three consecutive and similarly designed releases for Landfill Editions between 2016 and 2019 – Book of Void, 4 Fragments and the recently published Twin Mirrors – wherein the Dutch artist explores the grazing grounds of wordless storytelling, though there are small onomatopoeiae left to be discovered in the first one. In their latest book, by juxtaposing a manual process of creating with the challenge of searching for knowledge, Hachmang's art style evolves into a more pencil-driven one, marking a departure from the former heavy use of partitioned flats drenched in luminous paint which were prominently shown on the inside wraparound for the 2015 Landfill anthology Mould Map 4. Therein they staged a conflict between future human capital and corporate henchmen, ruggedly separated by primary colors.

Viktor Hachmang did three consecutive and similarly designed releases for Landfill Editions between 2016 and 2019 – Book of Void, 4 Fragments and the recently published Twin Mirrors – wherein the Dutch artist explores the grazing grounds of wordless storytelling, though there are small onomatopoeiae left to be discovered in the first one. In their latest book, by juxtaposing a manual process of creating with the challenge of searching for knowledge, Hachmang's art style evolves into a more pencil-driven one, marking a departure from the former heavy use of partitioned flats drenched in luminous paint which were prominently shown on the inside wraparound for the 2015 Landfill anthology Mould Map 4. Therein they staged a conflict between future human capital and corporate henchmen, ruggedly separated by primary colors.

With meaningfulness already mentioned, the overall theme of Mould Map 4 had been Europe, fatefully bound but still torn apart by its implicit frontiers. Glory, glory, how we wait in Europe, a quilt woven out of segmented patches would make a fine analogy for Hachmang's former drawing mannerisms stemming from the arch-European Ligne Claire, in the same way as the archipelagos of the Philippines are emblematizing Alex Niño's megalomaniac panel layouts.

Mould Map, which explores boundaries and borders as well – not only those within Europe, but also the ones of editing and publishing an anthology – furthermore seemed to be geared towards an ending of all formats curating comics. In 2016 their fifth installment came along as just a stack of loose-leafs held together by cardboard and an artfully designed rubber band. Followed by an exhibition without any printed equivalent, Mould Map now exists as an online anthology alone.

At least an online display doesn't leave you with the risk of your exhibits being severed by cutting-edgy assassins, as happened to Barnett Newman's abstract expressionism painting ''Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III'' in March 1986. The man responsible for this attack, Gerard Jan van Bladeren, unintentionally laid the groundwork for Hachmang's Book of Void thirty years later on, because "In the void is virtue, and no evil" – the most clean-cut advice you can receive from swordsman Miyamoto Musashi's writings on martial arts called Book of The Five Rings, to which the title of Hachmang's comic, lifted from one of the chapter headings out of Musashi's book, refers.

At least an online display doesn't leave you with the risk of your exhibits being severed by cutting-edgy assassins, as happened to Barnett Newman's abstract expressionism painting ''Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III'' in March 1986. The man responsible for this attack, Gerard Jan van Bladeren, unintentionally laid the groundwork for Hachmang's Book of Void thirty years later on, because "In the void is virtue, and no evil" – the most clean-cut advice you can receive from swordsman Miyamoto Musashi's writings on martial arts called Book of The Five Rings, to which the title of Hachmang's comic, lifted from one of the chapter headings out of Musashi's book, refers.

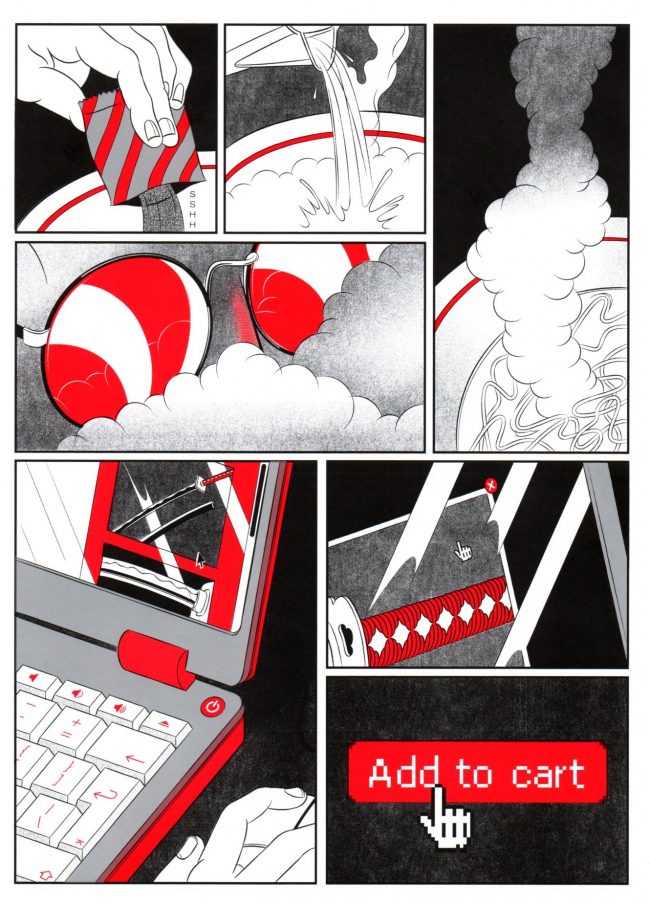

Book Of Void appears to be a psychogram of the vacancy within a person, whose inner fulfillment can only be achieved by pushing their interior emptiness into everything that already exists, developed here by using a samurai sword which replaces van Bladeren's box cutter. This brings up questions about the process of creating by devastation, i.e. does van Bladeren, a Netherland-ish artist himself, serve as a source of inspiration for Hachmang's work? Hachmang's motive for choosing a painting by Piet Mondrian – another Dutchman and much more interestingly, a representative of constructivism – instead of the one actually destroyed in 1986, can't be attributed exclusively to randomness. Take note of the national issues implicated here in the willfully assembled Dutch conglomerate but also of the fact that the first attack on Barnett Newman's painting was executed in 1982 by a German claiming that the painting was a “perversion of the German flag”. Europe, an artistic endeavor as a result of martial philosophy, wherein the sword or box cutter is mightier than the pen or brush – or a continent brought to a boiling point, as is water with an electric water jug like the one the wanna-be samurai uses, who ordered their weapon of choice for applied art criticism online? Other gear to keep things in states of matter are Thermos bottles that play an important role in Metallization, the third of four stories appearing in Hachmang's second Landfill release 4 Fragments from 2018, where a robotic system – a nod to GERTY from Duncan Jones' movie Moon – collapses when recognizing its likeness reflected in the surface of its beverage. The motif of amalgamation is omnipresent here, for example the glutton feasting piggishly on slain goods in Mask and then merging with something that looks like a fetish mask of a horned hunting god out of pagan witchcraft.

Book Of Void appears to be a psychogram of the vacancy within a person, whose inner fulfillment can only be achieved by pushing their interior emptiness into everything that already exists, developed here by using a samurai sword which replaces van Bladeren's box cutter. This brings up questions about the process of creating by devastation, i.e. does van Bladeren, a Netherland-ish artist himself, serve as a source of inspiration for Hachmang's work? Hachmang's motive for choosing a painting by Piet Mondrian – another Dutchman and much more interestingly, a representative of constructivism – instead of the one actually destroyed in 1986, can't be attributed exclusively to randomness. Take note of the national issues implicated here in the willfully assembled Dutch conglomerate but also of the fact that the first attack on Barnett Newman's painting was executed in 1982 by a German claiming that the painting was a “perversion of the German flag”. Europe, an artistic endeavor as a result of martial philosophy, wherein the sword or box cutter is mightier than the pen or brush – or a continent brought to a boiling point, as is water with an electric water jug like the one the wanna-be samurai uses, who ordered their weapon of choice for applied art criticism online? Other gear to keep things in states of matter are Thermos bottles that play an important role in Metallization, the third of four stories appearing in Hachmang's second Landfill release 4 Fragments from 2018, where a robotic system – a nod to GERTY from Duncan Jones' movie Moon – collapses when recognizing its likeness reflected in the surface of its beverage. The motif of amalgamation is omnipresent here, for example the glutton feasting piggishly on slain goods in Mask and then merging with something that looks like a fetish mask of a horned hunting god out of pagan witchcraft.

In all of these stories the protagonists experience some sort of synthesis with lifeless objects or vice versa. The drawing styles differ, though: while Metallization, Mask and Humidity, the latter showing a probably lethal conflation of flesh and matter, hark back to a style still rooted in the Ligne Claire, the opening story View from Nth Point is placing characters drawn in a more expressive style against a setting composed out of artificial and more clearly outlined accessories to visualize the clash between archaic and progressive tendencies – which turns out to be the overall theme of 4 Fragments in the bitter end, as it is told in the closing tale Humidity.

In all of these stories the protagonists experience some sort of synthesis with lifeless objects or vice versa. The drawing styles differ, though: while Metallization, Mask and Humidity, the latter showing a probably lethal conflation of flesh and matter, hark back to a style still rooted in the Ligne Claire, the opening story View from Nth Point is placing characters drawn in a more expressive style against a setting composed out of artificial and more clearly outlined accessories to visualize the clash between archaic and progressive tendencies – which turns out to be the overall theme of 4 Fragments in the bitter end, as it is told in the closing tale Humidity.

The style Hachmang's established in View from Nth Point shows up much more vividly in his third release, Twin Mirrors. Its first story, The Hermetic Library, presents once again a clear-cut environment mainly composed out of books about arts, design and architecture, comics' mostly unrecognized stepbrother. A backpacker, wandering the endless halls and corridors of a library is once again an organic lifeform getting thrown into objectified knowledge. They end up between shelves of gigantic proportions, climbing, struggling, and finally, discovering. But the knowledge they'd been searching only pushes them back in the circle of research, leaving them marked or better, a stigmatized person, destined to wander the paths to perception eternally. Obviously there's also a beautifully composed page where the protagonist is pushing the doors of said perception, so now it's about time to remind you of Aldous Huxley's famous book The Doors of Perception, wherein they stated that our brain and nerve system are responsible for a filtering process to protect us from getting flooded by an information overload.

The style Hachmang's established in View from Nth Point shows up much more vividly in his third release, Twin Mirrors. Its first story, The Hermetic Library, presents once again a clear-cut environment mainly composed out of books about arts, design and architecture, comics' mostly unrecognized stepbrother. A backpacker, wandering the endless halls and corridors of a library is once again an organic lifeform getting thrown into objectified knowledge. They end up between shelves of gigantic proportions, climbing, struggling, and finally, discovering. But the knowledge they'd been searching only pushes them back in the circle of research, leaving them marked or better, a stigmatized person, destined to wander the paths to perception eternally. Obviously there's also a beautifully composed page where the protagonist is pushing the doors of said perception, so now it's about time to remind you of Aldous Huxley's famous book The Doors of Perception, wherein they stated that our brain and nerve system are responsible for a filtering process to protect us from getting flooded by an information overload.

This theme of the book is mirrored, yes, in its follow up story, ironically entitled Synopsis. We're introduced to a guy behind a typewriter, doing an enormous amount of paperwork that ends up on a huge pill, which is slowly threatening to take over the room. The only thing we see of their writing results is an 'i', within this whole context a dummy for information. In addition, I'm seriously tempted to toy around with “type to write nevermore” here, but I don't want to risk getting sued by Warner, otherwise Reynolds will kill, or even worse, not pay me.

This theme of the book is mirrored, yes, in its follow up story, ironically entitled Synopsis. We're introduced to a guy behind a typewriter, doing an enormous amount of paperwork that ends up on a huge pill, which is slowly threatening to take over the room. The only thing we see of their writing results is an 'i', within this whole context a dummy for information. In addition, I'm seriously tempted to toy around with “type to write nevermore” here, but I don't want to risk getting sued by Warner, otherwise Reynolds will kill, or even worse, not pay me.

Anyway, the creative session concludes, and the typewriting guy fades out into empty panels and blank pages synonymous with the very void, where this artful trilogy had once begun. You're welcome to enter it.

Anyway, the creative session concludes, and the typewriting guy fades out into empty panels and blank pages synonymous with the very void, where this artful trilogy had once begun. You're welcome to enter it.