The following conversation was conducted at Inkwell’s End, Guelph, Ontario, on August 25, 2018 by Dominick Grace and Eric Hoffman. It has been edited by Dominick Grace, Eric Hoffman, and Seth.

Dom: Congratulations on the completion of Clyde Fans.

Seth: Thank you. The book is at the publishers, and they are doing all of the post-production work. They’re still scanning pages, still making corrections.

Dom: I know when we last spoke (in 2014; published in Seth Conversations [University Press of Mississippi, 2015]) you were talking about perhaps doing some revisions?

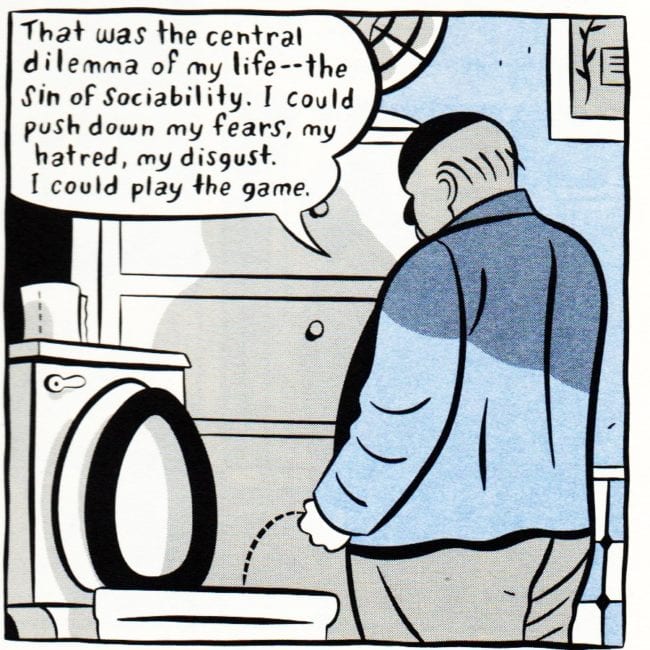

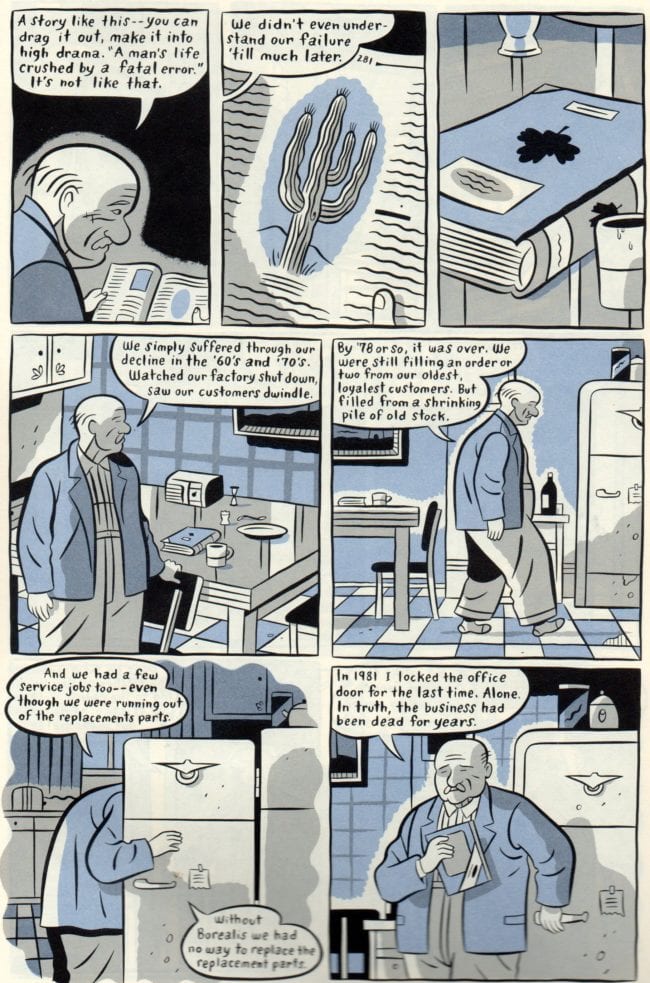

Yes, there are a fair number of revisions, but they are not the kind of revisions that people will immediately notice. I didn’t rewrite huge sections of the book, not a tremendous amount of re-drawing either. The changes occur mostly in Part Three—that’s where I really fiddled around. In Part One, I mostly corrected the color—trying to fix up how I applied the blue and grey tones back then to make them jibe a little better with the later work—but not dramatically, just attempting to make the book look more consistent. In Part Two, there were a few sequences that got fixed up, not much, but in Part Three, there were major changes. I cut pages apart, or I added in pages or fixed storytelling that was awkward. The main thing that I changed—the section I was waiting for years to change— was the sequence I did of Simon talking to his toys. This was a sequence I always hated, and I always thought it came off really corny. And it bothered me. Almost the moment it went into print I knew it was bad. I rewrote that sequence many times over the years to fix up the awful dialogue but it was always unsatisfying, and then finally about a year ago, I got what I think was an inspired idea, which is I took all of the toy’s dialogue out of the story. So, Simon’s talking, and there are only empty word balloons responding. A simple solution but it solved the problem of the corniness of that exchange. That sequence had come off like a bad horror movie sequence or something. It was crummy. Now I feel so much better about it. Thank God I finally figured out how to handle it in time for the collection. I had thought, this scene is a stubbed toe —but now it ties in much better with a couple of other oddball sequences in the book. It feels right. I’m very pleased about that.

Dom: That’s interesting because one of the things that I noticed when re-reading Fans was that it had felt like the style had changed a lot more than it really does. There’s actually a much more consistent feel to it then I previously noticed.

Oh, good.

Dom: But especially with regards to Simon, it was deeply creepy. I want to say not like a bad horror movie, but it had that kind of a Twin Peaks vibe to it.

Well, I kind of went for a weird vibe with that, and, as so often happens when you go for a weird vibe it ends up as an obvious vibe. And that was the key problem for me, as I said, this feels like somebody trying to create something weird, rather than maybe having the proper emotional tone naturally come out in the storytelling. Overall, I hope the middle chapter will still have a slightly otherworldly feel to it, but I pray it won’t have the clichéd element to it that it had when I first put some of it down on paper. I’ll leave that for you to decide when you see it. Sometimes cartoonists will correct things in their work—I’ve encountered this myself as a reader, where I’ve read other people’s work, and then they’d fixed it up and of course, the cartoonist thinks it’s much better, and you’re like, “oh, you kind of wrecked that.” So, you never know. Maybe I’ve made a mistake fixing anything.

Dom: The second thought isn’t always the best thought.

Do you remember Jaime Hernandez’s story “Hundred Rooms” back in the early days of Love and Rockets? It’s about issue five, or something. It’s a big long story where Maggie and Hopey go and stay in Costigan’s mansion and there’s a big party. I thought this was a very great story at the time. When Fantagraphics started reprinting the work in the very first collections, Jaime fixed that story up and added about five pages and changed this and that. I remember even then I thought, “he flubbed it.” He was trying to clear up some plot point but something delicate disappeared in the correction. I preferred the original. So you never know how people are going to respond to changes. But of course you’ve got to go with your gut.

Eric: The tone for that scene with the dolls did seem a little jarring, though not necessarily in a bad way. It did seem a little out of place when viewed in context with the rest of the work.

I’d been waiting so long to get to that scene when I was drawing the story, I was very anxious. I thought, “Oh boy, when I get to that scene, I’m really going to love that scene.” And then almost immediately after it was published, I was like, “Eh, didn’t work.”

Eric: I think withholding the dialogue might make the scene even creepier.

I think so. I think it makes it that much more obvious that it is an interior dialogue that’s going on. Not something supernatural. And I dialed back a lot of what was being said there. It seemed too obvious or trite…even dumb. So it’s iffier now—less clear what exactly is being said—because we’re only getting Simon’s responses.

Eric: Right. Did you change his dialogue at all?

Yes. Simplified his responses. Made them less specific, but enough dialogue happens that you can guess at what’s being said without it being too clear.

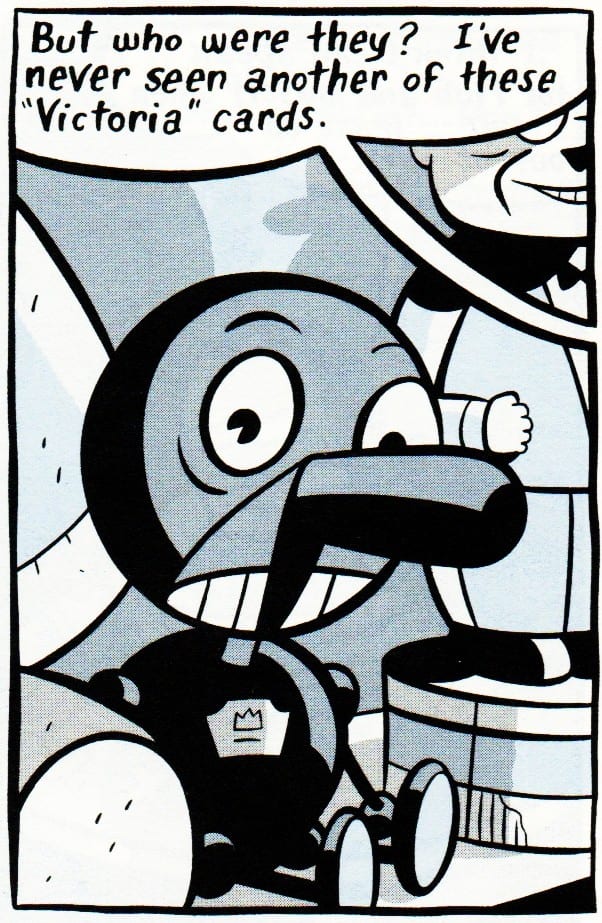

Dom: While we’re on the toys specifically, the one toy, the one with the black nose… Talk about creepy. Is that based on a real toy or is that something you yourself designed?

It’s funny you mention that, I changed that element, too. That toy was based on a Halloween decoration. Very loosely based. It’s funny, when I was working on the book, I missed an obvious point there, that Halloween toy is clearly a black racial figure. I’d incorporated that element without fully realizing it and the moment it hit me I knew I had to make that point clearer so I went in and fixed that up in the artwork. It’s totally obvious now. And it needed to be because it reinforces a point I was pushing earlier in the story when Simon purchases the little “pickaninny” doll he’s from the traveling salesman Whitey. I mean, this was an obvious connection and I flubbed it. I looked at those pages and was like, why did I not do that clearly? Somewhere in my subconscious I was connecting it with that other doll anyway, but I had not made it obvious enough that even I knew what I was doing. Now maybe I’ve gone too obvious, but those racist images aren’t in the book by accident and I’m glad I’ve thought this through fully now and that I know why they are in there. I’m often called a nostalgist but I’m aware of the racism and misogyny of that white man’s world I’m portraying. I don’t want some golden fog of the past.

And since Clyde Fans has a strong main thread about the disappointments of progress, it was important that the closed world of these brothers not be a cozy retreat from reality -- not allow any simple ideas about the world being better in 1957. Why is it that Simon goes back to his room with the racist toy instead of any of the other cheap novelties Whitey was peddling? Because the vulgar toys are a symbol of emasculation, humiliation, servitude and the loss of human dignity, something Simon is allowing to happen to himself but is also complicit in.

Dom: But the original was based on something you’d seen?

Yes, I looked at a lot of books on old Halloween decorations and this image came out of that process.

Eric: So it’s supposed to be a minstrel doll?

Yes. It’s supposed to be a minstrel figure. Or I should say, my original image for the doll comes from the tradition of minstrel imagery. Like a lot of pop culture images do.

Eric: That’s funny; I didn’t pick up on that.

Dom: As soon as you mention that, it’s kind of obvious.

Eric: Yes, it is.

It’ll be even more obvious now. It just needed a couple of easy corrections—the obvious stereotypical elements. No one will miss the point, trust me.

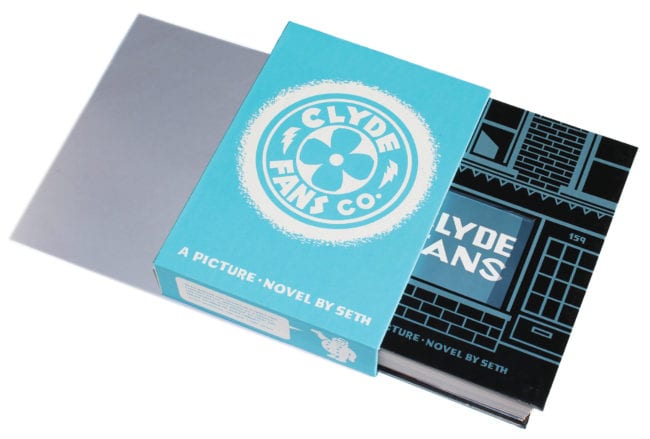

Eric: Will it be two books in a slipcase?

No, one book in a slipcase.

Eric: Because in our previous interview with you, we spoke with you about this and you were sort of on the fence about the format.

Well, a couple of things made that decision clear. And the biggest thing would be the changing of the company from Chris Oliveros to Peggy and Tom. Originally, Chris Oliveros was still considering that perhaps we could do a second book and then maybe we would put them together into a slipcase or something. I’m not sure I ever even discussed this with Peggy, but when the regime changed I think it was simply understood by everyone, including myself, that that old idea made no sense whatsoever. The collection would be one book. I mean, let’s be realistic—this is a book where the primary audience will never have even heard of Clyde Fans: Book One [published in 2004 and now long out of print—DG and EH].

It doesn’t make sense after ten years or more to bother with that old format. In an ideal world, maybe I would have followed through with book two. On some level it would have been nice to do a second volume that matched the first, but I don’t think I even broached the idea. A single volume containing the whole thing just seemed logical.

Eric: Abe was on the cover of the first collection, and Simon was to have been on the second.

Originally, that was the way it was going to be, and that would have been nice. I still would have liked to have done that—it hurts to leave that design idea unfinished. But realistically I knew everyone was leaning toward a single volume, just because it makes financial sense, it would sell better, and the new audience is going to wonder why there are two books. I mean, we’d probably have had to reprint volume one just to make that plan work. It just makes sense to put out one single nice fat volume. So that’s the way it’s going to be. And to be honest, I’m glad.

Dom: Do you know when it will be out roughly?

I think in the spring, 2019. It certainly feels like the end of a phase of my career, that’s for sure. I feel very much like I’m dividing my life right now. Clyde Fans and then everything after.

Dom: I guess you’ve spent close to half your life serializing it.

Oh, for sure. It’s been twenty years, I think. It was started in ’97 and I finished it in 2017, so… It’s funny, twenty years sounds like a long time when you’re young. But when you’re older, it’s like, “ah twenty years, I barely noticed those twenty years passing.” 1997 still feels like six years ago to me. Somebody’ll say, “Oh that was ages ago, back in 2008” or something and I’m like, “what, 2008? That’s not a long time ago.” But with young people… You meet a young person who’s 22, and you talk about 2005, that’s a lifetime ago. 2005 feels like just the other day to me.

Dom: I still think of stuff from the ‘90s as new.

Oh yes, me too. I don’t know any of the music from the ‘90s because it was too new. My wife talks about music in the ‘90s when we’re in the car listening to the old folks’ channel, something comes on from the ‘90s and I’m like, “what’s this?” I stopped listening to contemporary music sometime in the late ‘80s. Everything from the ‘90s sounds too new to me. When I say “modern music” I’m talking about the 1990’s. That stuff is already on the oldies channel!!

I’m really out of step with the culture, but, even so, there are the odd things that creep into my consciousness. Right now I’ve hit a technology gap. For years, I could always watch anything on a DVD, but now because I’m not streaming or on Netflix or whatever, I have no way to see a contemporary film if it’s not in the movie theaters nearby. I need to make the technological jump to some other system and yet I can’t dredge up the interest to bother figuring it out. They simply don’t make a DVD of anything anymore. And you can’t rent anything any longer either. All the video stores are gone. There was a time, even ten years ago, where I would go down to the video store, and we had a very good video store here in Guelph, and you’d be like, “okay, here’s a modern film. this looks interesting.” Now I’m out of the loop. Entirely.

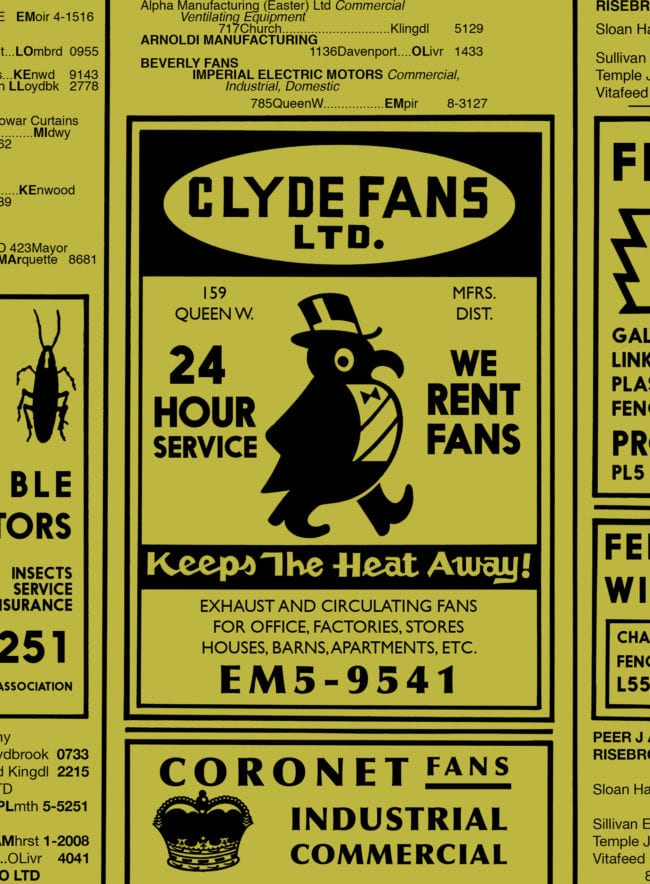

Eric: Speaking of technologies fading away, and recognizing that you’ve told this story many times before, it perhaps bears repeating: why fans?

It’s simply that there was a real Clyde Fans. It was a storefront at King and Sherbourne in Toronto. In fact, the building is still there. It’s a clothing store now. For a long time it was a gallery and still had the words “Clyde Fans” on the front. Sadly, they’ve scrapped the old hand painted lettering off now and not a scrap of evidence remains to show the old fan business was ever there. So yes, it was an old storefront and it looked exactly like the storefront that I draw in the comic.

I’ve told this story many times. I passed by it all the time in those days. It was already pretty much of out-of-business when I first noticed it. I would look in the window, into the dark office— very much like the office in the story—and on the back wall were two photographs, as I have in the book, of two men that, in my memory, looked much like the brothers I ended up creating, although to be honest I can’t really remember what they looked like now, it’s been so many years since I last saw those dim photographs. But yes, there were two men and I often thought, “who were these guys? What were their lives about?” and that simply was the origin of where Clyde Fans came from. I had no particular interest in fans, and in fact actually at first I was going to change the name because I thought, "Oh, well maybe I shouldn’t use the name of the actual business—the real place.” I was going to call it Boyd Fans I think, but then I was like, "Oh, who cares? Nobody's going to know about this or anything. It's in a comic book. No one connected to that old store will ever see this comic story.”…and you know what—I guess that nobody ever has because I’ve never heard a word from anyone connected to the real Clyde Fans business. This is the funny part about it all: I mean, imagine if your father had a fan business and it was called Clyde Fans, or your grandfather. Wouldn't you have Googled it by now to see if there was anything on the internet about it, and wouldn't you be surprised if there were hundreds of references to some comic book called Clyde Fans? After you looked into it and saw that the comic was clearly based on your father's store, wouldn't you contact the guy who's doing this book? I have never heard a thing from anyone. I find that downright odd. So, what does that say to me? It says that there's no family left. It didn't carry on beyond these fellows. Maybe they died bachelors, I don't know, or maybe the last family members are too old to be internet-savvy. Or maybe they are just not the type to reach out and contact. It strikes me as strange though. I would have thought for sure by now somebody would have said, "Hey, that was my uncle's store," or something of the sort. For example, I’ve run into people ... there's a guy I see every year at TCAF [Toronto Comics Art Festival] who comes up to me every year and talks to me about how I drew his dad's antique store in It's a Good Life, If You Don't Weaken. For the first few years I was like, "Oh, yeah, yeah, you," but now when I see him coming I'm like, "It's the guy whose dad owned the antique store." So it's funny that, yeah, the only reference to Clyde Fans on Google is pretty much my book. You can't even find much of anything there about the real fans themselves. And, of course, there are real electric Clyde Fans. I’ve got a huge Clyde fan sitting out there in the porch. They exist. If you look around you can still find them occasionally. They've got little metal tags on them with the company name. They weren't a huge manufacturer, but I'm literally surprised that there is such a pittance of information about them online.

Eric: But the idea was to center it on a fading technology.

Exactly. I was—

Eric: That was the central impulse—

Yes, the metaphor that drew me to it. At that point in time I was probably still formulating a lot of my feelings and opinions about all the change that was occurring in the culture.

Eric: Because technology is something that changes so rapidly, especially in the 20th century.

The funny thing is—well, yes, I obviously I was trying to make some kind of a direct overt commentary about changing times and technology in those first issues of Clyde Fans, but in retrospect, I look back and I laugh at how completely computer illiterate I was at that point. I'd never even been on a computer then—never even moved a mouse. I don’t think I sat down in front of a computer until sometime around 2002 maybe. So in the early section where Abe is talking about technology changing, that's mostly just reflecting my antagonism towards the computer technology I was feeling at the time but without any real understanding of it whatsoever. Just sensing it encroaching into my life and dreading the change it was bringing to the world. Essentially, I think all the technological change I'd experienced before that was somewhat gradual—relatively unnoticed. A technological change that one accepts without thinking because one is used to a kind of step by step progress. You know, we all saw televisions go from black and white to color, records to cassettes, incremental changes ... I remember my brother in law having a home computer in the '80s and it made no impression on me whatsoever. He was like, "You want to look at my home computer?" And I remember thinking nothing of it. It wasn’t any different than when he showed me his de-humidifier. I'm like, "Yeah, whatever.” I did not recognize what was coming at all.

Dom: I remember the first time I saw one, I thought, "who would want this?"

That was what I was thinking. I recall asking, "What is it for?" But by the time I was writing Clyde Fans I was definitely thinking about the effects of big cultural change and getting kind of frightened by it. I was seeing it firsthand in my work as a commercial artist. That field was changing. Suddenly artwork was being scanned rather than being sent physically to the printer. The technology wasn't so good in the first couple of years too. So a lot of the early reproductions in the magazines were really quite crappy. The color trueness was really off when they'd scan from a watercolor painting, and the pixelization was really apparent in the early years, and I was thinking to myself, “this is a definitely step down.” It didn’t even seem like progress. I was irritated that I was being dragged into a world that I had no interest in. I sensed that soon I might be forced to learn a bunch of technological skills that were anathema to me. Although now, here we are 20 years later I will freely admit the technology has revolutionized things, and the printing today is much superior to what I was used to back then in the 90s. It's incredible the quality—the reasonably priced quality you can get because of—

Eric: So you spoke too soon?

Exactly. In some ways, although in other ways I’ve stubbornly stuck to my guns. I'm still with Abe in his basic ... the basic point he puts forward in the first chapter. That you can get rolled over by technology. I feel right now I am being rolled over by technology—social media, the internet, the nature of how human interaction is changing. I’m feeling like I’m a pin in a bowling alley. It's incredible how much change has occurred in the last ten years, and that I'm not ready for it. I'm sure you guys must feel it as well.

Dom: The only social media I'm on is Facebook.

But you must be aware the dialogue that's going on online. The way people ... it's like… how do people relate to each other?

Dom: Trolling each other, yeah, it's not been good for civil discourse, that's for sure.

I think we're living in an odd period. We're living in this period that they'll probably look back on in the same manner as the Wild West where they'll say, “Man, that was a confused period." Something or other will undoubtedly change in the next twenty years that will sort out this mess. It’s got to change. This can't be the way it's always going to be from now on.

Eric: I hope so.

It's leading to societal chaos, I think. In the future they'll look back on all this and say, "These were the years before we figured out A, B, and C," because right now I think ... I just don't see this as culturally sustainable. We are in trouble.

Dom: Well yes, it's in theory democratic access to information. You'd think it'd be a good thing.

It should be.

Dom: But the most insidious thing that it's led to is the annihilation of the concept of truth.

That's one thing I've been thinking about and of course following so closely what's going on with Trump.

Eric: Giuliani's recent statement, for example.

Exactly.

Dom: Truth isn't truth.

Yeah. It’s interesting how quickly we absorb each day’s chaos and then move on to the next. It seems to me that what's happening here is a complete breakdown in all the societal norms that keep our societies running smoothly. You've got people now who are saying things like, "Who cares if ... these crimes don't matter." It's like, now we'll admit they're crimes, but—

Dom: They're irrelevant ones.

They're irrelevant ones. That's a big shift from ... you couldn't have had that without this dividing line of alternate media where people are only believing one thing or the other and there are no longer the old gate keepers that set the standard of what truth is. Now you could make good arguments that that was a bullshit system too, and that you couldn't necessarily ... that when you look through the history of 20th century government and media that people were being lied to consistently and facts were hidden and etc., etc., etc., but it did mean you had a common ground of information. Now, it's like you can't even talk to each other because it’s a matter of you've got your talking point and I've got my talking points and they have nothing to do with each other.

Eric: There doesn't seem to be a consensus reality anymore.

That's problematic, and the more people dialogue exclusively through digital means, the less likely they are to be reasonable about it—to even consider meeting in the middle.

Dom: Yes, because no one's close enough to punch you in the nose for saying something really nasty.

True, in regular life you wouldn't be so nasty. If I was talking ... I went out to lunch recently with an acquaintance I hadn't seen in ten years and when we began talking I started in with my anti-Trump talk and then suddenly I realized he's a Trump supporter, and I was like, "Oh, I didn't expect that," but I didn't say to him, "Fuck you." I was polite and accommodating— like, I was surprised, disappointed, even a bit disgusted. It wasn’t entirely out of character but still—supporting Donald Trump!! But whatever ... we had a conversation about it and at a certain point it was obvious we simply came to a wordless decision not to talk about it any more.

Dom: We'll agree to disagree.

Exactly. So in effect, I was being more reasonable towards Donald Trump and he was lessening his active support. We could meet in the middle with, "Well, I can see your point, but," and then we moved on to other topics, and I thought this is the way people used to behave because they had to. But online you're like, "Fuck you and fuck your children, and I hope you die of a horrible cancer," and this is not how people should talk to each other.

Dom: No, it's toxic.

So we shall see what happens, but anyhow, enough of Donald Trump. My life doesn't revolve around Donald Trump.

Dom: We can leave this out of the transcription if you want.

I don't care. I'm fine with it, but my poor wife— she's like, "I've heard enough about Donald Trump for two lifetimes."

Eric: When I crossed over the border I felt an enormous weight had been lifted.

Ha-ha. It’s interesting because I was never much interested in American politics before. I couldn't tell you much of anything that went on during the Obama years. All that mattered to me was everything seems fine. So it's like I'm not ... I wasn't checking in on Obama every day. Not at all, and in fact, I'm not checking in on Canadian politics every day. I get the basic news from the printed newspaper in the morning and that's enough. I don't need any more than that. Even when the guy I dislike, like Doug Ford here in Ontario, I'm not obsessively following what Doug Ford's up to. Somehow it's very different with what's going on with Donald Trump.

Eric: Very different.

I'm not following Brexit every day. There's a cultural breakdown of norms that's going on that's very unique here, and we're living through interesting times.

Eric: That's the Jewish curse.

Yes, exactly. Here is one thing that Trump will be happy about— in the future when they talk about American presidents he’ll be right on the tip of everyone’s tongue. The big names, Lincoln, Jefferson, and Washington, Teddy Roosevelt and FDR, JFK, Nixon, and Donald Trump. He will be one of the presidents that is talked about forever. He won't be up on Mount Rushmore, but he will be ... people will be like, "Name a president." He'll be among the first few people named for 100 years. Longer even. Anyhow, back to comics.

Dom: You were saying a few minutes ago, this is a question we had coming up anyway, but since you mentioned how you’d been looking forward for a long time to getting to the point where you would be doing the toys sequence, that fits with my impression when I was rereading it as a completed work that despite the length of time the serialization took, it feels like it was very carefully planned.

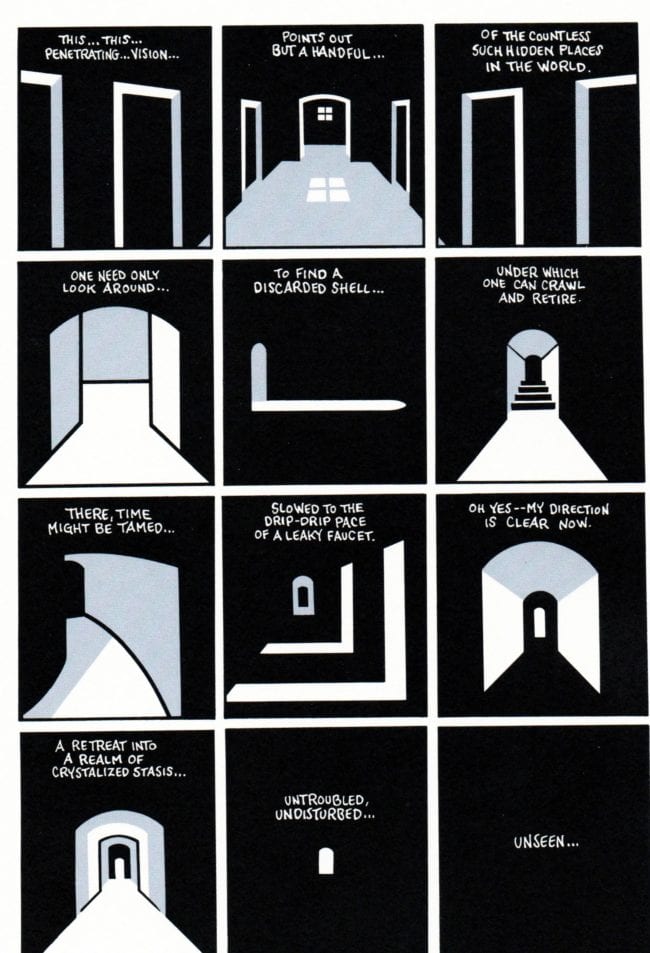

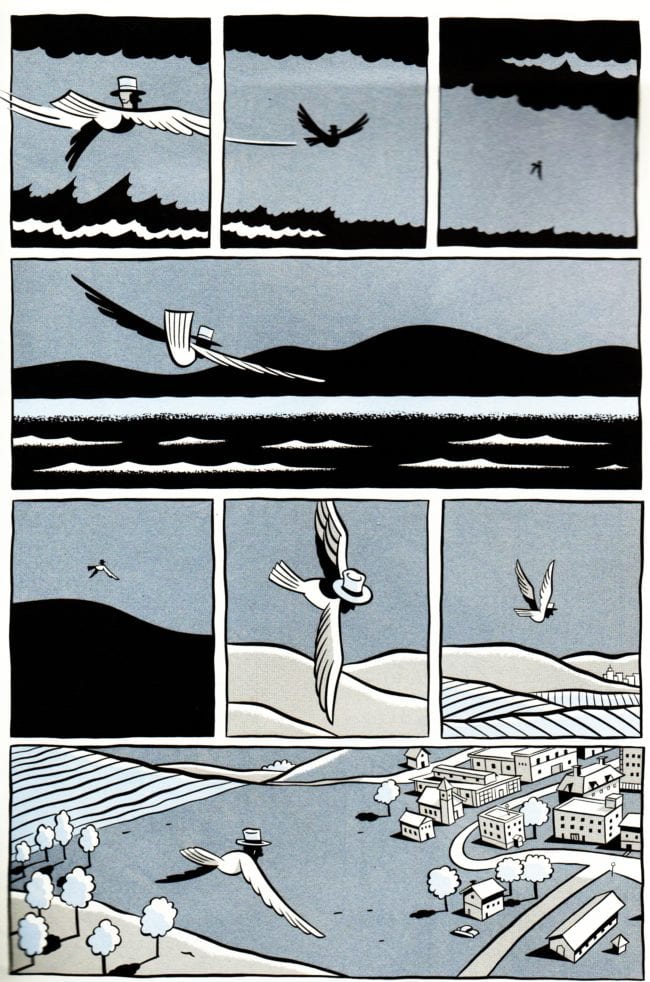

It was, although there's two sides to that answer. It was very carefully planned, but it was not written in advance. So just about every single thing that happens in the book was planned back in '97. Every scene basically, although vaguely. So I knew, back then, that in the final chapter, for example, after his vision concludes there would be a silent sequence where he walks to the train station, and then I could see I wanted to have a long sequence of the train and then back in Toronto, all the way back to the house.

I didn't have any ... I hadn't given it any real thought to the very images themselves or how the pages broke down. I just knew that would happen and when I got to that point in the story I was ready to execute it. I knew the arc of the scenes for every section, but I didn't bother to write anything beyond copious notes because I knew that it would be far too boring a process to write a script and then draw it over a long period of time. Even when I initially came up with the idea of the book and I planned that Clyde Fans would take about five years to do, I still was like, that will be far too boring for five years work. So, of course, I plotted it all out in point form and then spontaneously write each section as I went along because that in that way it was easy to my interest alive. Ultimately, I’m glad I did it that way too because after such a very long time you change—I mean, you yourself change, the way you think changes. Probably if I had actually written it all out as a script I’d have had to rewrite it every few years. I mean, the story itself wouldn’t have changed but the subtleties of how I wanted to get those scenes across would have evolved. That’s the irony of the book. The story evolved over time…and yet it remained essentially exactly as I planned it.

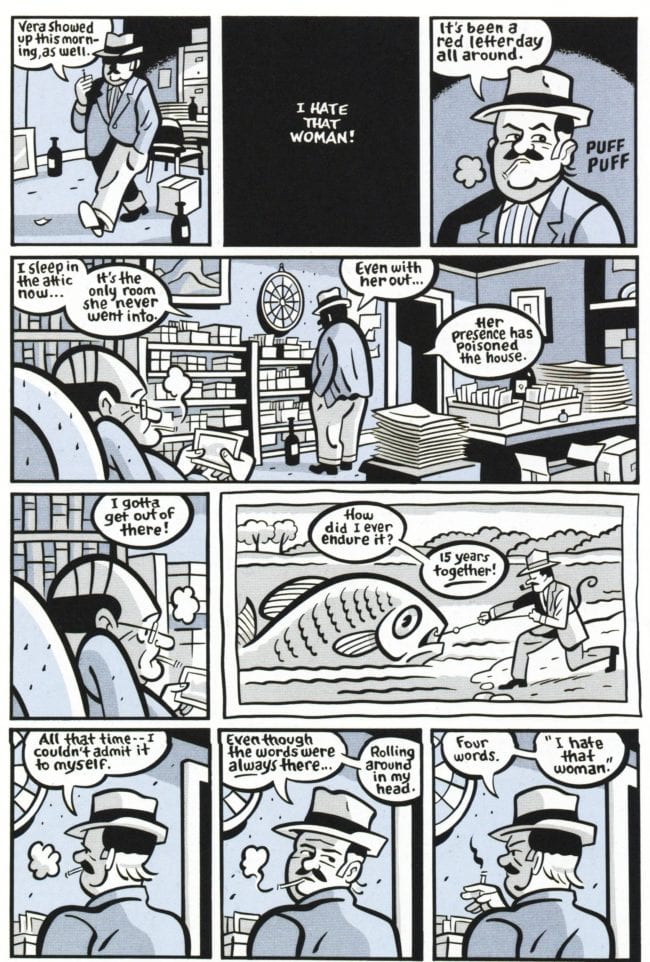

Dom: That's where I was coming from with that. It took twenty years, but it doesn't feel like the point of view or the ethos or the informing ideas change over that time, and you do see that sometimes with serialization where someone clearly changed their conception. From an artistic point, there must be an interesting and challenging aspect to doing that.

It’s funny. I wasn't trying in any way to keep any dogmatic consistency, but I think it might just speak more to the fact that I've had a consistent set of interests over all those years. Certain things have changed, of course, in that time and perhaps say, how I might pace a story has changed, but the underlying tone of what I was doing hasn't really changed much in twenty years. I’ve been on a very consistent thread of thought for decades. It narrows or widens, but I think a certain way. Even the work I'm doing today, I can see that I might have still been attracted, back in ’97, to the story I'm writing at this moment for my next book. What might have changed is my understanding of why I'm interested in these things now. I think that when I wrote Clyde Fans I didn't really know what I was writing about, why I picked this particular story or why these particular characters or what any of the underlying qualities in the book are about, or "about" in quotes. Now I think I know why I would write such a story. I look at the work and ... except for a couple of minor things, this old story is pretty much exactly the same themes I'm interested in writing today. Over the years I've said to myself repeatedly, "What do I like and why do I like it?" So you watch a movie and you say, "I like that movie. That really appealed to me, but ..." and often what I'll say is, "... but I wish they had stayed in one contained location." Or, "...too many characters," or whatever. You have a qualm of some kind. Then eventually over the years, especially when you’re a writer as well, you say to yourself, "What's the ideal story I'd like to write so that I could read it?" Often that takes a really long time 'til you figure out what it is you're actually interested in. It seems obvious, I know. You'd think, I'm interested in blah, blah, blah, so I'll write about that, but when I look at Clyde Fans now I think, "Well what was I interested in there enough to make me write that story?" Clearly, for example, I’m interested in isolation. I like the idea of characters that exist in isolation and how they deal with it, how they deal with loneliness or being alone. I like a very limited environment. So most of the story takes place in the Clyde Fans building. If I were to write that now, knowing what I think about it now I might have set the whole thing in the building and never have them leave the rooms at all. I like a low amount of conflict in a story. So even with Clyde I’m like, there's too much conflict in the way I wrote it. The scene where they come together to talk, it's kind of an argument. I probably would have lessened that if I'd planned it today, and because I find that when I ... well, almost anything I watch or read today when I get to the end I say to myself, "I wish there'd been a little less conflict in that."

Eric: I think probably one of your main criticisms of anything is there's too much going on here.

It's true; I always want to narrow things down, make them flatter. It's funny, there's some process of acclimatization that occurs through repetition... I mean, if you like something a lot, a film or a book, and you return to it over and over again, the level of emotional conflict gets lessened by the simple fact of familiarity—of knowing what's going to happen. So there's certain things I love that are conflict ridden like say, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? I love the film version and yet it’s literally fighting and backbiting from the first scene 'til the last, but at some point the nature of the experience changes; once you've watched the movie 50 times, it's no longer stressful. Actually I watch it for pure relaxation—the pure enjoyment of the repartee between the characters or whatever. So I think a lot of conflict has to do with the initial encounter. A lot of books I love have a certain amount of conflict in them as well, but once the conflict is resolved then I'm happy to read it a second time. Generally the thing is, I've realized I don't like tension in a story which I suppose is usually the opposite of what they're telling you makes a good story. Isn’t conflict/tension considered the basis of any solid piece of fiction? I feel that's an oversold element in how we write fiction. It's one of the first rules they will tell you when you're writing something, “where's the conflict?”

Eric: Man versus man, man versus himself, man versus nature?

Yes. If you're taking a creative writing course or something and you hand in your low conflict story they'd say, "This is really flat. There's no conflict, you know, whatever." It's interesting that we've placed such a high value on that aspect of drama. Some of the things I probably most enjoy are ... and in fact, in almost every book I read lately I find myself really paying attention to the slower sections—I’ll say to myself, "Pages 70 to 89 were great. Nothing happened. Then unfortunately a big fight occurred on pages 90 to 99 and I lost interest.” I’m almost always saddened when the plot picks back up. Everything was going along so nice and slow and dreary and then…blah blah blah. So there it is, a lot of yakking to just point out the simple idea that over twenty years I've figured out what I most liked, and fortunately a lot of it was in Clyde anyway. Nothing much happens in the story, which is just peachy with me.

So getting back to the final sequence, the out of body experience, that was something that I didn't realize why I put that in when I first wrote the story, but today, it is blatantly obvious to me that I have some sort of a... I guess I would say a mystic bend in my thinking. I'm basically a materialist, but I have a very strong feeling of unreality about reality as I am sure most of us do. That said, I feel like ... when I look back at almost everything I write, there's always a scene where a character somehow tries to deal with the more profound nature of mundane everyday life, and that final sequence in Clyde Fans was particularly ... well, maybe the essential Seth plot point—somebody coming to an interior experience of the unreality of life. I think ... I may have always felt deeply interested in this specific sensation, even when I was a child or a teenager maybe, but I wouldn't have put my finger on it and said, "This is a story point that interests me." Over the years that element has grown stronger. More pervasive. So the book I'm planning out right now, it's got a good amount of that mystic element to it, for sure.

Dom: That's one of the things that struck me rereading it. I mentioned before the sense of the uncanny about it, that there's a feeling in the book that there is sort of a subterranean or extra-material world. Especially for Simon. I love that moment where he steps in the crack in the wall, and that's a completely mundane statement and yet it's completely impossible.

Yes, I was pleased with that particular sequence—not so happy with the toys—but that crack in the wall worked because it was a simple flat statement that sets up the idea that Simon is involved in another level of reality or perhaps a hallucinatory experience, but the toy stuff felt too forced for me. I think that's the tricky part for me was trying to get that in between tone. Somewhere in that sweet spot between mundane and fantastical. Hard to do. You mentioned Twin Peaks. Lynch is particularly good at creating a separate ... particularly good at capturing that reality that this isn't reality. Do you know Inland Empire well?

Dom: I've seen it, yes.

That's my favorite of his films, and as I watch it more and more, the most remarkable element of it is the shifting sense of reality. The characters are doubled. They change identities, character traits…in some odd way that is what real life feels like. He’s getting at something complex there. He recognizes and portrays that odd sense you feel in life that perhaps you might have been somebody else, or maybe in the back of your mind you almost remember a different life. If you thought hard about it you might think, “Oh, no that's not true. Maybe that's just a dream," but there's a strange shifting quality to reality that you wouldn't ... I feel like I wouldn't be the least bit surprised if suddenly it was revealed to me that this life was a dream and this had all been a dream, and you’d say, "Oh, well of course. It felt like a dream. It couldn't have been reality, could it?”

Dom: Makes sense now.

Yes. Exactly.

Eric: With regards to Simon's sort of hallucinatory state, mental state... there’s an ambiguity in Clyde Fans because you're not sure if that's contributing to his isolation or if it's the result of his isolated state.

It's a good question, and I'm not sure I have an answer.

Eric: I hate to say, but there's a tension there.

Yes.

Eric: It's not a conflict.

I don't mind if there’s some tension. It's true. I like a bit of ambiguity in a story, and that's another thing that I've realized over the years is that everybody likes a mystery, but most people don't really care for the solution of the mystery.

Eric: This gets back to David Lynch who puts the mystery at the forefront.

Exactly, and a lot of people don't care for Lynch because they want answers.

Dom: Even if they don't like them, they want them.

…and when they get the answers it almost always deflates the experience. So, myself, I like ambiguity in a story, and I'm not entirely sure what any all of my own work means either. It's much like Simon's vision ... is that vision ... is there any truth in that vision? Is there actually anything revealed to him that's true, or like you say, is that vision a response to his own fear? Is it what leads him into retreat? I feel that the first time through— when people are reading the book serialized— nobody would have been understanding, in Part Three, where I'm showing how the vision fails Simon, because the reader hasn’t experienced the vision yet. It’s just hinted at. When you read it I’m clearly showing that the vision has not lived up to what it promised, which is an exquisite world of isolation and decay. Instead it has solidified into a prison of loneliness for Simon. So, there’s a lot of ambiguity, in that I haven't made up my mind either whether that vision at the end is representative of something that is beautiful. A crystal cave of exquisite solitude, whatever words I used, or if it is literally the hallucinations of a deluded person who's consigning himself to a mistake.

Obviously in real life I would’ve advised Simon, "You need to get out." That is not the answer. Poetically, I’m encouraging him to stay put.

Eric: I think also, though, in a way his isolation acts as a metaphor for the life of an artist, and you do imply that he has an artistic sensibility, since he's working on the book that he never gets around to writing. So there's that isolation that the profession sometimes demands, and I'm speaking personally as a writer, that feeling of the distance from one's audience, of being anonymous, and yet at the same time having a persona that's public in a way. Having one's life at work at best misunderstood and at worst completely disregarded. Abe's speech about Simon reflects this. He's talking about himself, but he might as well be talking about Simon. He's saying, "It's funny how long he could simply be doing what he's always done no matter how futile, day in, day out while the world goes on without noticing." Simon also recognized this anonymity and disregards the results from his isolation. Yet at the same time he considers that isolation a necessary condition of his experiences of profound feelings. You say that the "unfortunate irony" of his prerequisite of isolation is that there's no opportunity to share it. Simon’s resigned to the fact that the artist must ultimately come to terms with this irony.

I often think this is the basic dilemma of loneliness is that ... or loneliness verses being alone—is that being alone is an essential quality to experience certain things. Certain things you only experience or you experience deeply when you're alone. Earlier when we were talking about the drive you took to visit here, that drive is a deeper experience when you're on your own because you notice things in a different way. You're not distracted by conversations with other people. Your senses are somehow more alive.

I recall a trip to Hudson, New York, a couple of years ago, I went there, and I had a terrific afternoon where I walked around the streets on my own, just looking at the town, and then I walked a long time trying to find a perfect spot to have lunch. Finally, I settled down in this cavernous Mediterranean restaurant and I was reading a really good book, drinking a couple of glasses of wine, and I had no responsibilities in life whatsoever. That day is burned in my brain as a really, really exquisite afternoon because it was that perfect experience you can only have when you're alone. Now, I could think of other experiences that go a few years back in time when I was single and very lonely walking around by myself on a book tour or something. When you're miserable, you’re often not actually experiencing things more deeply, or maybe you are, but the desire to share them with someone is so deep that it actually undercuts the value of being alone. There's an interesting dichotomy because almost always if you're alone long enough you start losing the wonderful quality of observation and experience and contentment and the alone time begins to transform into the interior experience of loneliness. When you're lonely all you really experience is being lonely. You walk around saying to yourself "Oh, I'm lonely. Nobody cares ... Why can't I find a girlfriend?" or "Why doesn't anybody like me?" Eventually you've turned inward and so you've lost that precious quality. I'm extremely interested in loneliness because I'm extremely frightened by it.

The times I've had real loneliness in my life have been a little close to madness because they were so filled with anxiety. They were probably closer to panic attacks. Really, the kind of thing where you can't stop thinking about your dilemma. You can't sleep. You can't enjoy anything, and so I'm pretty terrified of that experience. It takes all the pleasure out of life, and that's one of the reasons why I think I'm so interested in the idea of isolation because on the flip side of that terrible loneliness, I'm really, really happy when I'm by myself and content. I mean, I’ve almost always been happy alone. I grew up as basically an only child, but not a lonely child. The difference always was, when I was a child, it was mother and me and that cozy little world of two kept loneliness at bay. and now it's my wife, Tania, that supplies that emotional balm. These figures, Mother or Wife, do not need to be with me all the time—far from it—but they give me this powerful buffer against loneliness. Just the knowledge of their presence. Knowing I am not actually alone in the world makes all the difference. When I'm in the studio alone and Tania's at work at her barbershop I'm very, very content and happy. I know I'll see her later in the day. We'll have a good time together. I don't feel lonely for one second. Sometimes I'm in the house for weeks on end without even stepping out the front door, except when I go out with her on the weekends. Most of the time I never even think about anybody else. But, if she were to die or leave me, probably after a couple months the whole day would be long dirge like "Oh, another gray day alone in this horrible house, how can I stand it?” It's interesting how perspective shifts.

There's a series of artists I'm particularly interested in because they were either isolated or alone —just interested in how they dealt with it. I can't remember, last time we talked I may have mentioned this list of artists then too. I’m often thinking of them. My own little pantheon of lonely artist. Anyhow, to return to what you were talking about—about Simon's dilemma being comparable to the experience of being an artist—hmm, well, what I think essentially differentiates those two experiences is that Simon isn’t involved in communicating through his art to others. He’s alone. I've talked to Chester Brown about this a few times, more than a few times, where we say, "Would we still be doing comics if nobody really cared? Would we have given up years ago if we were just putting out a Xerox comic and few people cared? I mean, maybe, but you're not really getting much feedback?" That feedback of positivity is so essential to allow you to keep working. When I started out, I was unsure of what I was doing, like all young artists are, but now I'm very sure of what I'm doing. It's not simply because of a natural progression of skill by which you do get better, but it’s confidence. That changes. Eventually, if you get enough positive feedback, you're no longer bothered so much by the negative feedback or even the lack of feedback. Let’s face it, you don’t develop confidence in a vacuum. If you get little or no feedback to your work... well, jeez, I’m always impressed by people who continue to put out work when they're getting almost no feedback—then you must ask, "Why are they doing it? Is it just for themselves?" “Can you be that self focused? That confident and secure?” Of course, that sense of doing for yourself has to be a big part of any kind of artistic endeavor, but let’s not kid ourselves. It's never just about that alone.

Dom: Otherwise you wouldn’t publish it, right?

Exactly, just put it in a closet. You want feedback, and probably there's not a single person who doesn't create some work and secretly (or not so secretly) hope, somewhere in the back of their minds, that someone's going to say, "This is the greatest thing I've ever seen." Who doesn’t do that? I mean, you always have the same two opinions of every piece of work you finish. "This is great," or "This is terrible." Usually you have both. Usually about the same work. What changes is that over time, when you’ve received enough positive feedback over the years, is that you stop worrying and say to yourself, "This will be received fine." Chances are nobody's going to say "Finally, they've revealed themselves to be a complete idiot." Not at this point. They'll just be, "It's more of what they do" or if you are lucky somebody might say, "It's the best thing you've ever done." Occasionally it’s, "Oh, this is the sad sign that they're heading downhill," but generally the confidence comes from communication, and without that communication I'm literally not sure how people endure, how they keep doing the work. Some people literally do continue to produce ... Well, there's another point too. I was about to say continue to produce really tremendous work that nobody seems to care about, but that's actually stacking the deck because then they probably have, from a small quarter, perceived the kind of feedback where somebody says, "This book of monoprints or this poetry is tremendous and I love it." One letter even, or some important things that a few people have said to you, or one good review or something in a small magazine, but it's quite different than absolutely an indifferent mention in a zine about what you've done. That's not going to keep you going for twenty years. Then that's where I'm particularly interested in artists like Henry Darger, who did all that work in private. You say, "Why were they doing it?" I’d guess Darger was doing it to save his life because he would have died if he didn't have that artwork. It was an interior world to live in. That's a very different use of art than I’m what I employing to construct my next book. That's a really different experience than most artists.

Eric: That's like more the therapeutic theory of art.

… which is extremely interesting, but you know it didn't make him happy. Working on that did not bring happiness, but it probably brought a kind of day-to-day ... salvation…I mean, I can relate to that somewhat. When I was a teenager I came home every single night and drew these shitty super hero comics that I was totally into because that was a more interesting world to me than the world of high school, and I needed that.

Eric: That's a low bar.

A very low bar.

Eric: You could say that about Darger, that it was cathartic.

Yes, he was taking sustenance from that deep experience of immersing himself in fantasy. His landlord could hear him through the walls talking to himself in several voices. That's a total immersion—having conversations with yourself and you're playing both sides. You can’t write a story like that. You would never write that. It's too good. Or too corny. I’m not sure which.

Eric: It's kind of what Simon does, though.

It is, and that's why I had to tone that down. I've gotten off track here. Somehow that had to do with loneliness. There are artists I admire because these are artists whose work I love, or I'm influenced by—whatever. Then there's this other, smaller group where mostly it is their life story that is interesting. I do like their work as well, but I probably would like their work less if they had had a different life. Edward Gorey's another good example. I like Edward Gorey, but I like Edward Gorey a lot more for being Edward Gorey than I do for his books.

Dom: One of the things I was I think noticing more, rereading Clyde Fans, is that, and I think this ties in with what you were just talking about, Simon is, in some ways, a kind of visual analog to some of your avatar characters. Is there an element in which you see Simon as a way of expressing that aspect of what you were talking about, about loneliness and aloneness?

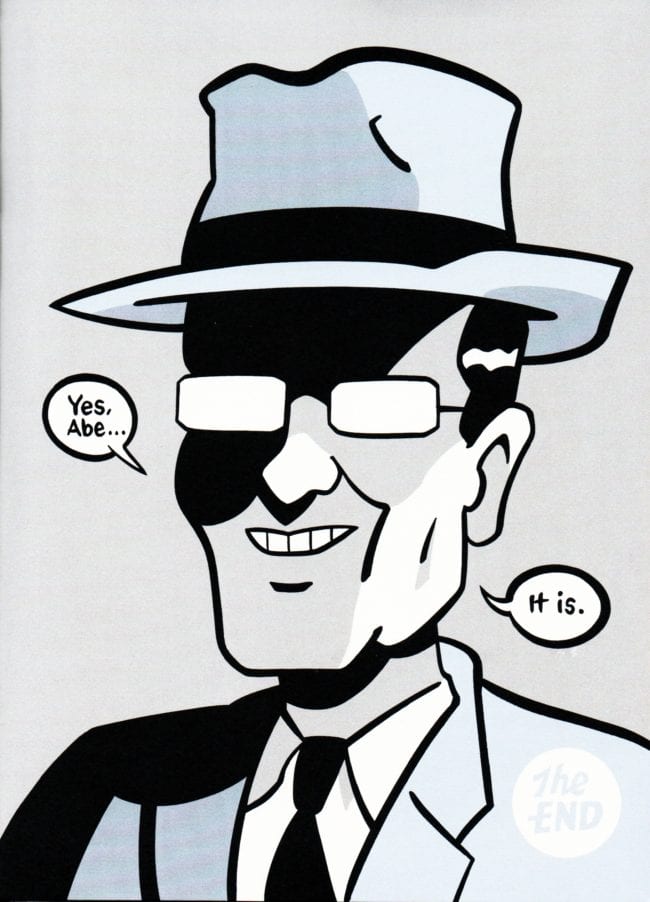

He is, for sure, but Abe is as well. They're both flip sides of the same person. It's funny though, with Simon, problematically he's drawn too much like some of my own self-caricatures. He's a bit more—he’s certainly thinner and he's a little more gnarled looking, but I actually feel like I've got to a point where I was drawing him and I'd gotten too used to drawing him. He was starting to merge with my own self-caricature. The problem with that is that I worry that a reader who doesn't know my work might find the various parts of Palookaville confusing. Mixing up the various bespectacled, fedora wearing protagonists. Or even the simple worry that someone might think I am using Simon entirely as a self-flattering avatar.

Dom: No, it doesn't feel like it was autobiographical or anything, but it seemed like it had to be a deliberate choice to make him resemble the Seth persona.

It wasn't deliberate. Not really. I just drew two 1950s types when I first started Clyde ... Going back, it's so hard to even remember what my thinking was because I didn't put a great deal of thinking into these initial character designs. I needed two characters, and these are the two guys I drew. One of them had a mustache and one of them had glasses. Then over time—

Dom: It's iconic, so they're easily recognizable.

Exactly, so you could tell them apart quickly. One would be heavier and one would be skinny. That made it much simpler, but I did know at the beginning that they were both going to be the two sides of my own personality. That was an obvious point that I knew from the word go. I think when I first started working in comics there was this idea that I was a reclusive person who was shy, which is not who I am at all. I’m, as you know, a very gregarious person. I talk a lot. Far too much. I’m not a person who's quiet. Often, when I meet people they would be like, "Oh, you're a lot more outgoing than I expected you to be,” So, when I was first working on these characters I knew I wanted to take the two sides of my personality, the very extroverted personality which would be Abe, but also the introverted me. Essentially I think of myself as an extrovert who doesn't value extroversion. I value introversion. Simon is more the quieter side of my life.

If you're a very outgoing person you often end up being filled with a kind of low level self-loathing. It's a natural thing that if you go out and you talk and talk for hours, then you come home and you have this experience of what I call “the physic hangover.” You're like, "Oh God, I talked way too much. What was the thing I said? That was so stupid. Oh, I would like to take that back but" blah, blah, blah. Then when you spend five days by yourself and a calm descends— you’re like, "Those were five great days because the only person I'm dealing with is myself." When you're by yourself, your true self comes to the fore in some strange manner, maybe that's an illusion, I’m not sure, but you're not reflecting off of anyone else and that makes a tremendous difference. So much of the experience of talking to other people is what is bouncing back to you from them—you see yourself reflected back and very often that is off putting. I wanted to deal with two characters who were those two types, my extrovert and my introvert. It gave me a perfect opportunity to have Abe be the much brusquer character and Simon to be the much more reluctant one.

Eric: Simon, albeit to a much more extreme and probably less well-adjusted degree, like you in a way, kind of lives in a self-constructed world. There's a comfort to that, but can't you also regard that, as with Simon, as a kind of prison?

For sure, I do recognize that. Although as you get older, whoever you are—you become more of that person.

Eric: In a way it's also freeing. There's a dichotomy there.

There is. I don't think it's so freeing for Simon. He has constructed a prison. I feel like he's made ... I feel the vision he experienced, it was a misleading choice in his life. It was probably his one opportunity to change, and instead it reinforced the worst choice he was already making—which was retreat. Retreat; in my own life I favor retreat. It's something that I value deeply, but I recognize that it is not a quality that society value and when I talk to people about choosing to opt out of certain things I can just sense that most people don't see retreat as a healthy choice. It's interesting that people are ... If you talk about getting older the thing that is always valued when people are getting older is how much they remain in contact with what's changing and with youth ...

Eric: But that in its own way is imprisoning. I see people walking around with their phones. These gadgets take over their life and then by you saying, "Well, I would rather not do that" they respond, "What's wrong with you?"

It's very true. I think the good thing about getting older, like you were saying, is it is freeing because you no longer need as much approval. This ties in again with the positive reinforcement idea; at a certain point in your life if you've had enough positive reinforcement you become more confident too in making choices that are outside of society's pressure. Well, within reason. We're all conformists so you can't really get away from that, but you can say, "I'm not going to get a device,” for example. That’s not much of a stand. You’ll take grief for it but it’s a little thing. I've refused. My wife has one and I've seen, even with her, it taking over her life. I catch her when I'm going to the kitchen for a second. I see she's checking something on it. I've told Drawn and Quarterly I will not get one for traveling or book tours or whatever. I've already capitulated and got a laptop. That's more than enough. If you need to contact me, send me an email. I will check it in the morning, at night, whatever.

I do think that as I grow older I'm much more confident in doing things because they're the way I like them rather than just being purely reactionary. When I was younger ... I used to always make fun of Chester, that he was a contrarian. It seems like every choice he was making it was just to be the opposite of what you're supposed to do. I used to make a lot of fun of him about that, but at some point I realized I think I’ve pretty much been doing the exact same thing. Sadly, being contrary often means taking a stand against things that mean nothing to you. For example, someone might say, "Have you seen Breaking Bad?" I'd be like, "No, I am not interested in any contemporary television shows." But why? Why am I not interested in any contemporary television shows? I might even trust the person’s taste who is recommending the show, but I will still reject it. It’s like, "Why would I refuse to watch that show?" It's just contrarianism. I'm just taking a stand on something that's totally unimportant. Just stubbornly refusing to keep up with the culture. I’m not proud of this stubborn silly behavior, but it is a fact and isn’t likely to change. For me, that is the type of character I’ve grown into. I’m not going to make any effort to “keep up” because it’s expected of me. I just don’t care. I’m following my own little thread. On the flip side of that, though—you do come to recognize that there are certain areas where you're literally being left behind. You don't know what's going on any more. You feel that there's a tipping point you passed where the culture has somehow moved on somewhere else now and you don't know anything about popular culture any more. I think I've hit that point. I don't know the name of any modern singers. I don't know what any of these video games are people are playing. I might see the occasional contemporary film, but not too many. I'm not unhappy about this, but it is an awareness that, "Yeah, I'm totally out of the loop now."

Eric: With Simon, then, in a way is his depiction of your thinking through, "Well, this is the darker side," or this where this sort of isolationism can lead essentially?

I think it's the recognition. In Simon I see the danger of where isolation leads to ...

Eric: Mental instability?

It's the difference between, again, the difference between being alone and being lonely.

Eric: There's a healthy level of isolation.

Exactly.

Eric: Then an unhealthy level.

Yes.

Eric: He's gone way beyond.

He has, although Abe doesn't fully see that because somehow or other by the beginning of the book Abe sees Simon's struggle as somehow laudatory and even at the end of the book when Abe goes back to live in the Clyde Building, you know that it's because he's decided that Simon is somehow correct and made the right choice to retreat, but is that a right choice? I'm not really sure that I have a concise answer for that.

Dom: The value of retreat with dignity?

Yes. I do believe that both the characters are fighting for some kind of dignity. I understand that. Getting older that's exactly what I'm thinking too, how to maintain yourself in this culture with dignity. It's not a particularly dignified period we're living in.

Eric: It's kind of guilt by association isn't it?

It's funny. I look at the internet and I think it's interesting that it's a let-it-all-hang-out culture, and I'm not sure that I'm 100% behind that idea. It's not prudishness. Nothing shocks me, or it's not censoriousness ... I am opposed to any censorship, but I certainly don't think we should be ... I think what it is, is just that—the culture is lacking in any kind of dignity at the moment. It’s like “Hey, I just shit my pants. Who wants to see it?" My feeling—there are things that we should keep to ourselves. There are ways that we should interact with each other. There's a veneer needed to maintain dignity that isn't just ... It's about formality, but it's not about being trapped by formality. I feel like we haven't hit that point yet where our society has said, "We don't want to be trapped by formal custom that inhibits us to be happy or free, but we also don't want to live in this complete, undignified, let-it-all-hang-out culture either." There's got to be a middle way.

This is why I have such a dislike of the era I grew up in, the '60s and early '70s. This period where the hippie culture officially took hold. That's when we threw the baby out with the bath water. Don’t get me wrong—there was plenty of bath water to throw out. I certainly wouldn’t have been happy living in the 1950s with that particular culture, but somehow or other that period of the ‘60s to the early '80s was a miasma of change that didn't necessarily lead, I think, to an obviously better culture. I mean, that was an interesting period. A break that had to occur— where they had to, of course, throw away a lot of that early 20th century thinking. Social progress is important and the changes in society made a world where I can do what I wish and make the kind of work that I wish. The monolithic quality of the Western culture has totally fragmented. And that’s all good. However, the vacuum left by the discarding of the tone of the old culture doesn’t feel right to me somehow. This is one of the things where I sometimes crave for more formality, where I say, "There doesn't seem to be enough effort being put into things.” Maybe it’s just personal inclinations— I liked a culture where you went out more, where you had to dress up for things. I liked a culture where people had more interest in aesthetics or ritual or whatever, blah, blah, blah. It’s a messy argument.

The current culture feels cheap and junky to me. It's about instantaneous pleasure rather than long-term accomplishment. Even just in the arts, or in the popular arts, I feel like there's a strong pressure to get something out every five minutes before people lose interest in you. I was just thinking that the other day, "I haven't had a book out in quite some time. Thank God that Clyde Fans book is coming out because I don't have a new work at the moment." It's like after a couple of years you're totally off everyone’s radar. Whereas I’m not losing sleep about whether people are “talking” about me or not, I do care that if you're off the radar people stop calling to offer you opportunities where you can make some money. It's disturbing to me just how quickly everything is moving right now. I don't feel like the people would be ... It would not be a wise move right now if I met a young artist and they told me, "I'm thinking of doing a book that will take me 15 years to do and this'll be the only thing I'm working on." I'd say, without doubt, "That is a terrible plan because you need to get your name out there." People have to see what you're doing, practically every day, or else you can't build a career. That was not so true when I started out. Not true at all.

Eric: Right, there are these YouTube performers, I guess you would call them, and there's been news stories about these people having mental breakdowns, committing suicide because of the incredible pressure to produce content and to produce it constantly.

And for that content to work its magic and get enough people to care. You can imagine how stressful that must be.

Dom: You were talking about how that it's kind of crummy, people don't dress up anymore, and so on. It seems to go hand in hand with what we were just talking about. Ultimately it comes down to ethics, doesn't it? It's an ethical consideration, as far as how we are determined to act responsibly toward each other.

Yes.

Eric: ... in this agreed way of being, decorum, civilized behavior and so forth, and how it's degenerated.

Politeness is a basic formality that you would think everyone agrees on, this goes back to what we were talking about earlier, but that's not the case. You will have people who will say, and to your face too, not just on the internet, they'll say, "Ah, that's just bullshit." Why should I pretend to be nice about something when I don't believe in it? They’re making a case that politeness is hypocrisy. No, that's not how politeness works. You needn’t get into a disagreement with every single person you're talking to. That's not valuable. There are all sorts of unspoken rules that people—there's a certain kind of attitude that polite behavior is simply bullshit. I call this the “keeping it real culture,” which basically appears to me as just an excuse for self indulgence. Maybe it’s just old man stuff, but I honestly believe that politeness is the oil that keeps society moving smoothly. It doesn't work well if we don't have a certain level of formal behavior, and there is a limit to how much formality you can throw away before things fall apart. Yes, lots of commonly agreed upon values change within your lifetime. Nothing new there. Hanging around with Chester Brown, you get into these kinds of discussions constantly. He’s very good at challenging my complacent thinking. Lots of arguments about society and convention—prostitution, of course. Prostitution vs. romantic love etc. etc. Complicated arguments. Chester and I often disagree. I feel like in many arguments about prostitution and morality, he's got his own blind spots—where he's not willing to look so closely into some of the dark corners because it hurts his argument. Not that my arguments about anything are so tight that he couldn’t take them apart at a moment’s notice.

Dom: Well, isn't he, at the moment, in a monogamous paid relationship?

He is. Definitely, he's a monogamous john, which makes no sense to me. Makes no sense at all, but of course that's because he's an entirely odd character. Any other guy who was a big supporter of prostitution would be all about variety. I mean, the very purpose would be for sexual variety, wouldn’t it? Or convenience. It's funny, but that's Chester for you.

Dom: Speaking of Chester, and the whole contrarian thing, when you were talking about that a few minutes ago, this is completely tangential, but one of the things that kind of struck me, rereading Clyde Fans, is there's a kind of ... it doesn't feel like a very "Seth" moment, where early in the book where we actually have Abe urinating.

Oh yeah. Yes.

Dom: And I was thinking was that a Chester comment on the whole, you know, let it all hang out element in his work?

No, it wasn't a comment on anything, but now that you say it, it probably is more reflective of when I was doing that comic than anything else—during a period when I was probably trying to do comics that were a little bit more straight forwardly open about bodily functions etc. So you would ... I think the first part of Clyde Fans might be more connected to the earlier work I was doing back then. In Good Life, there's a couple of scenes where I'm naked or whatever. And I think I was probably trying at that point to do work, much like my peers, which would be a little bit more bold or honest, although there's certainly nothing bold about having somebody taking a pee. But I think later, I'd probably got to the point where it never even occurred to me that I should probably have a scene where Simon goes to the bathroom or something. I’d stopped thinking in those terms. That kind of thing was more connected to the idea of reality that people were trying to get in to their auto-biographical comics. I think there was a time where I was considering having some sexual fantasies in Simon's mind, but I wasn't sure when I got to that point in the story whether that fit the tone of Clyde Fans or not. And I think I was considering a scene that when he was taking his mother to the old folks’ home for the first time, that there would be some scene where he looked at one of the nurses and had some kind of a sexual fantasy of ... not very involved, but just enough to let you know he was thinking. To give some reality to the sexual side of the character. He so rarely saw any women, that maybe I would have had a mental image of her naked or something. I don't know. But whenever I did get to that point, it felt totally out of place. That no longer felt like a scene in a “Seth” comic. And I think, progressively, as I'm doing my work, I don't feel very comfortable writing about that kind of thing.

In my memoir that I'm drawing right now, Nothing Lasts, yes, I’m writing about sex and yes, there will be more mentions of sex, but it won't be particularly explicit in any way. Very mild. Very modest. I mean, I include my first orgasm and then I think I'm showing myself involved in a one-night stand at the end of the last segment. That's just the beginning of my sexual life, so there will be stuff about sex, but it will all be rather modestly presented. I don't feel ... it's not in my nature to talk openly about intimate matters in my work, but back in the early 90’s I probably was trying a little harder to be more naturalistic. If an old man is getting up in the morning, well then—he’s going to go to the bathroom. But I wonder if I would have bothered showing that if I drew that scene today. Hmm, I might have just had him flushing the toilet or something. I might not have bothered to actually show him urinating. I don't know.

Dom: It does, in a way, though, tie into something else that I was sort of noticing, which is ... and we've already talked about this to some extent, but you know, the very real focus on mundane reality—

Yes.

Dom: ... whether it's things like an entire page of fan designs or it would seem to be a kind of echo later when Simon is cataloging all of his mother's possessions.

Yes.

Dom: There was a real, and more of a very deliberate conscious sense, especially later in the book it seems, when the chapters are getting a little longer and more contemplative, that these artifacts, the day-to-day things, the things that we use on a daily basis, are ultimately what people are going to have left, and they're going to be us.

Absolutely.

Dom: I mean, someone peeing isn't in the same vocabulary, but it is still mundane, sort of.

It is about mundane reality. Well, you've hit on two points that are important to me. One is that you're right. I'm very interested in description. And that's something I've become more aware of as time has gone on. When I did the first chapter of Clyde, what I was focusing on was ... I wasn't thinking of it as description … I was thinking of it as moment-to-moment comic book story telling. So I wanted to make a point of that. If you have a guy get up and get out of bed and walk to the next room, you have to show it all. So, you follow the character around, and I know that was an approach that, back then, I was very interested in. I think of it as "naturalistic” storytelling. You basically follow the character around as they do things like you're a ghost watching them. So that meant that everything that occurred in the first chapter of Clyde had to be moment-to-moment. There would never be a jump. There might like a shift, you know, where you change from one perspective to the other, or it might be on the inside of a door in panel one, and then you cut to outside the door. That was acceptable. It wasn't like animation where you had to follow it directly. But eventually, I came to realize that one of the reasons why I was interested in that kind of story telling in the first place is that I'm actually really interested in description less than action.

I think if I was to write Clyde Fans again right now, in that first chapter, there probably would have been a long sequence where Abraham talks about the objects in the house. He doesn't really mention them much. I made it a point to show things, to give a feeling of each room, what was in the room, because I knew that later, you'd be coming back to those rooms in other chapters and I wanted the reader to always instinctively know the layout of the building. You always know where he’s going. But over time, I've become more and more interested in just the idea of describing things. Talking about them in detail rather than just pointedly showing them. For example, the sequence where Simon describes his mother's room, which is like ice cream for me—a total treat. I simply adore a good, deep description. A lot of the books I've been enjoying in the last few years, I really like when the author gives you three pages describing a church or something of that nature. Certainly, Proust is great for this kind of thing. You know, you've got 100 pages talking about the garden. Sometimes it can get a bit much, I admit, but I really do like that deep experience of looking closely at something. Certainly, in the new graphic novel that I'm working on at the moment, there's going to be a lot of that kind of description. Although I'm hoping, I'm still working out some of the details on this, but I'm hoping to mix it so you have the two things: The naturalistic story telling where you follow someone around in real time, and the deep description. These two approaches don’t always work so well together because deep description usually means a lot of narration and that doesn’t always go well with a smooth storytelling style. It often requires a lot of “jump cutting.” We’ll see how that comes together. Fingers crossed.

One of the things that I felt when I got to the end of Clyde, after I had drawn out that long vision sequence, which is somewhat naturalistic, but it's also jumps about, and got to the scene where he gets up and walks to the train; I was like, I don't do enough of this this slow style of storytelling any more. I said to myself, this is a kind of storytelling I really value, but you have to put the work in to do it right. It's boring to draw that ten pages of a guy walking from one place to another when you could do it in a page. You could do it in two panels if you really wanted to be expedient—panel one, off to the train station, and then, panel two, there you are coming in the door at the final destination.

To digress, one of the reasons why I'm even interested in that kind of storytelling ... this is something Chester and I used to talk about all the time back in the late 80s and early 90s … was you simply that you could do it. In the old days of comics you couldn't do it. Your editor said, here's your story—you’ve got eight pages. You didn't have any room to have characters walking for page after page. So there was a freedom and a luxury to be able to do that kind of languid pacing. In the course of any artistic career you change and the work changes, but sometimes you look back and you realize you may have gained in some changes and lost in others. So when I was working on that end sequence of Clyde, I definitely had a feeling of regret because I don't do enough of this kind of storytelling anymore. I’ve been doing more truncated kind of stories. More expedient storytelling. If you look at something like Wimbledon Green or The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists or even George Sprott, these are very concise comic books.

Eric: Compressed.

Yes, that’s the term. They’re very compressed. So, with George Sprott, those strips had to be compressed because they had to appear on one page, and then when I assembled it into a book, I added in extra material to slow the read down, and if you look at the pages I added, there's like a three or four-page sequences in-between the one pagers that allowed me to drop a bit of that naturalistic story telling into the mix. Without those sequences the story is much flatter. That naturalistic approach is just really powerful. There's something about reading a comic that mimes the rhythms of measured human movements that gets inside you as a reader. Did either of you read Nick Drnaso's latest book, Sabrina?

Eric: Yes.

Dom: No, I want to pick it up. I've recently been reading a lot of good things about it, but I hadn't even heard of it until a few weeks ago.

It's so great. And one of the reasons it's so great, there are pages and pages and pages of people getting up from their cubicle, walking over somewhere and doing something small. Nothing is happening, except a lot is happening, because it's a very intense book. The environments are boldly bland and modern. Offices, malls, whatever, where there's practically nothing exciting of visual interest, there's just shapes and hallways, and the characters are relatively bland looking too. It's really very powerful for that kind of ... it's funny when you really slow down on something where somebody takes a moment. You do this in ten panels where you're like, they're writing something and in the next panel they're thinking. Then they're maybe scribbling something out, then they're thinking again. When you slow down like that, that has a real narrative power somehow. Although, it sounds like it should be boring. But it isn’t— that somehow brings real life into the comics form in a way that you don't get with just some narration block over top of an image. So it's a powerful tool.

Eric: This also ties in to Clyde with its theme of time, I think, because the attraction Simon has for the postcards, for example, is that they depict this one frozen moment in time where there's no context. Everything's been sort of collapsed into this one image.

Yes.

Eric: And he seems to want that. He wants to stop time from progressing, essentially.

Absolutely.

Eric: Whereas, Abe looks at the postcards—specifically the one with the fisherman with the enormous fish—which Abe interprets as representing forces beyond Simon's control, Simon being overwhelmed by forces beyond his control. But both Simon and Abe are talking about the same thing, which is time.

Certainly the frozen moment of the postcard is alluded to in the vision when he's talking about kind of a vision of a perfect life, a frozen life.

Eric: Frozen life, right.

And this is, I think, again ... a quandary; that is, why am I interested in this idea? I'm not 100% sure, but the idea of a frozen life is connected to somehow being freed from the torment of human despair. There's something in freezing time into a moment—a big part of the vision is that it's saying to Simon, or perhaps Simon is saying to himself, that there is perfection in a kind of perfect stasis. Clearly that is what his character is longing for. And it seems to be presented as the answer, as well.

Eric: Well, he's being faced with loss, death, decay, not only of himself but of his mother, of his mental state, the business.