A scholar and artist, Simon Grennan’s practice is a fine example of cartooning and comics scholarship being intertwined.

A scholar and artist, Simon Grennan’s practice is a fine example of cartooning and comics scholarship being intertwined.

His artistic career in the UK started in the early 1990s, and he has since had books published by Book Works, Myriad and Jonathan Cape. His projects have often showcased his passion for Victorian culture, with author Anthony Trollope and cartoonist Marie Duval being two key protagonists.

Most recently, alongside Christopher Sperandio, Ernesto Priego, and Peter Wilkins, Grennan has been involved in Parables of Care: Creative Responses To Dementia Care. A free download produced in collaboration with the University of London, the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust and Vancouver’s Douglas College, the book is a 16-page comic formed of true stories told by real life carers of dementia sufferers (English and German language versions are available via https://blogs.city.ac.uk/parablesofcare/).

He currently holds the position of Leading Research Fellow in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at the University of Chester, where he investigates visual narratology and participatory fine art. His book A Theory of Narrative Drawing was published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2017.

In the following Q&A Simon speaks about his background and influences, as well as his passion for Duval and the role of “graphic medicine” and comics in healthcare.

Do you remember the first time you drew something you could consider “narrative drawing”?

Do you remember the first time you drew something you could consider “narrative drawing”?

When I was in infants school (say, age five), I used to collaborate (there’s no other word for this...) on large action drawings with three or four other kids in class. These drawings were made on very long rolls of cartridge paper, which rolled out as the drawn action progressed. We’d start drawing a scenario, which was usually a medieval battle outside a castle, and then draw the developing daring escapades and fights, progressing down the unrolling paper. We’d end up with a very long drawing in which characters and places appeared and disappeared over and over again.

One of the interesting things about this was the fact that gravity and direction were highly mutable (sometimes one edge of the paper was the ground or sometimes the other, or both, mixing multiple points of view), so sequence was the structuring engine. The final image wasn’t significant in any way. When time ran out, we stopped and hardly looked at the drawing again. Rather, the paper was the place where we could play with characters and scenarios in the manner of playing with toy knights, but instead of getting toys out of a box, we drew them and their activities. It was fantastic fun and very physically active, the opposite of sedentary drawing.

When did you first start (self) publishing?

Grennan & Sperandio, the international artists studio that I run with Chris Sperandio, has been publishing since 1990. Our first book was a little guide to a series of sculptural interventions in five churches in Chicago, titled The Body. Initially, from around 1990 – 1995, books and catalogues were a way for us to substantiate a studio fine arts practice that regularly produced no artworks, because it was socially determined. So the books often told the story of what had happened during ‘the art’, for the benefit of those who hadn’t participated (and the benefit of the careers of practitioners with no commodities to sell... i.e. us).

Then we stumbled upon the ‘situation’ of comics, or what I suppose I would now call the historic contingencies of comics. We got interested in the affective possibilities of multiple originals, collaborative productions and team productions with distributed processes. We recognized the contingencies of comics as including a habitually reproduced idea of multiple authors, the low status of work in the production chain, compared with the status of the final product, plus mass distribution, as properties that we wanted to adopt in our work. You’ll notice that it wasn’t the appearance of comics that was interesting to us, but rather the ways in which people made and used them.

Since then, among many other types of project across media, the company has published around 25 comics, most often showing stories that are written and edited by people we meet and work with. Most often, the drawing of the comics devolves to us. In visual arts terms, collaborative drawing means something quite different to the ‘corporate’ model that we adopt. We have always risen to the challenge of our both making drawings, by establishing rules for drawing (another thing that deeply interests me...). Creating and following these rules produces specific styles of drawing, regardless of authorship of specific drawings. Occasionally, we have given these rules to other artists and they have made our drawings for us. Of course, that isn’t quite the way in which I make my own comics, or think about comics, these days, in parallel with the work I make as Grennan & Sperandio.

I attended a half-lecture, half-practical masterclass you gave in Amsterdam last year. You're obviously very enthusiastic about teaching comics and cartooning. Has teaching always been a passion of yours? Did you have any tutors who influenced you to follow this line of work?

I attended a half-lecture, half-practical masterclass you gave in Amsterdam last year. You're obviously very enthusiastic about teaching comics and cartooning. Has teaching always been a passion of yours? Did you have any tutors who influenced you to follow this line of work?

My studio practices and drawing practice have always been searching practices. I’ve always liked asking and trying to answer questions or test propositions. As a result, my work has always crossed existing boundaries, methodologically and socially. For example, I have been able to demonstrate and explain complex ideas using drawing (such as in my theoretical writing), or to organize situations in which people do things that they don’t habitually do (which was the purpose of the Truce Tableaux project, made with artist and my long-time collaborator Chris Sperandio).

Studio practice and socially-grounded practices are part of a continuum of types of related experiences, for me. I consider everything I do as teaching and learning, academically or in practice. Sometimes, I’m learning, sometimes others are learning or, more often, we’re all learning! So I approach my historic research activities and my theoretical research activities as teaching and learning activities also.

I strongly believe that research leads teaching (if possible, given the constraints under which many people teach). Academically, I frame my teaching activities with my research. Back in the day, my own Masters tutors (such as Maureen P. Sherlock and Tony Tasset in Chicago, for example) and doctoral supervisors (Roger Sabin in London, for example) did (and do) the same.

I want to connect the dots a little bit between your life in the academy and your life behind an artist's desk. When did your fine arts background start to converge with the academy, or was it the other way around?

I’ve always worked across media and, I suppose, across genres. Although I have studio training in drawing and painting, the crafts of making have never constrained my work. The ways in which opportunities appear and in which ideas appear are too various for that. As I’ve said, I have a searching practice, which aims to ask and answer questions. Sometimes, these questions have been about craft (how to make something), but largely, they are about questioning an encompassing situation, that is, a social situation, habit or practice. That’s why my studio practices are almost always collaborative, for example, working with individuals or groups of people and other artists. As a result, I think of academic research as part of a range of activities that constitute my practice. That’s certainly not to say that academic work is vaguely defined for me – quite the opposite. I ventured into the academy so that I could ask difficult questions in a systematic way, with tested benchmarks for methods and outputs.

The function of consensus and review in the academy is quite different to the function of consensus in other areas of my practice, such as the fine art commercial market, for example. Hence, academic disciplines are a collaborative enterprise, with groups of scholars building upon each others’ work, sometimes over very long periods of time. Creating consensus, as to identifying and tackling the most pressing questions, is part of that process. I find that a very attractive idea. Of course, properly entering the academy requires training and accreditation. To become expert is to study! I received my doctorate in 2011, and my practice now encompasses both studio production and academic production. The connections between these activities is pretty visible if you visit my practice and academic websites.

Before your interest in the ‘situation’ of comics in the 1990s, were there particular cartoonists and illustrators whose work you found particularly inspiring?

My earliest inspiration came from diverse traditions. I grew up reading Albert Uderzo, but also the satirical cartoons of the British newspaper and journal cartoonist Michael Heath and the charmed drawings of the Danish illustrator Kay Nielsen. My enthusiasm for these artists was (and is) really generated by the different ways in which their drawing styles create the whole worlds of their stories and scenes. Retrospectively, I recognize performing arts traditions in the ways in which these artists place actions and situations on the page. They are not influenced by movie- or camera-derived framing, transitions or mise-en-scene in placing things on the page, nor do they use movie pacing. Their rhythms of visualization are quite different. Having studied the relationships between stage performance and comics in the nineteenth century a little, I can see their roots there.

One of the key figures in cartooning that your name is associated with is Marie Duval. How did you first come across her work, and the projects which subsequently arose, such as the book and website?

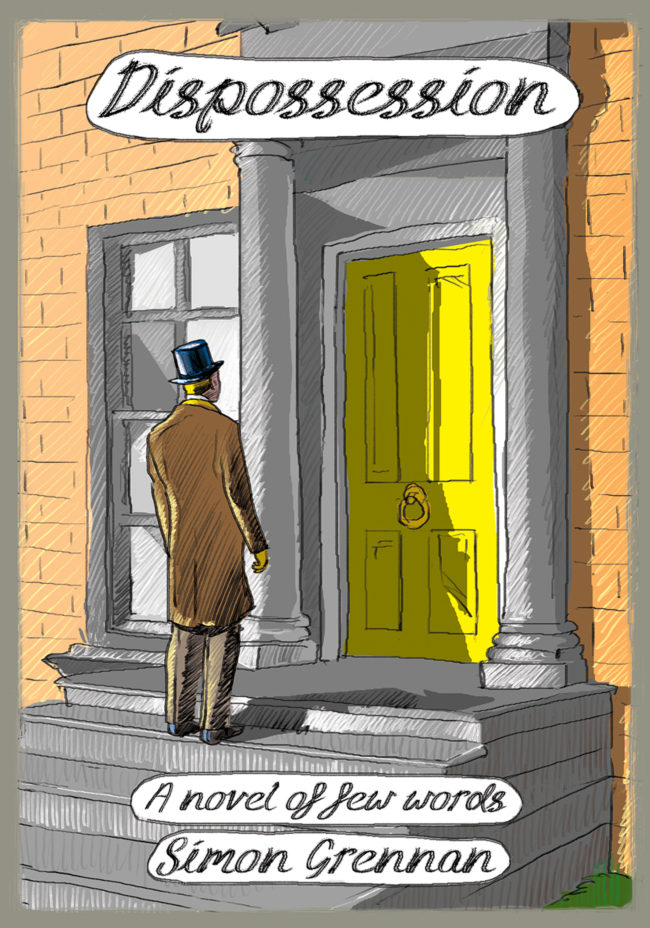

I’m delighted that you describe Duval as a ‘key figure in cartooning’! I certainly think so, although her work had not been a topic of much scholarly (or any other type) of scrutiny. David Kunzle wrote a germinal article, over 30 years ago. I started to look at her work seriously, with a couple of other scholars. I started to pay attention when I was beginning to draw my graphic novel Dispossession, my adaptation of Anthony Trollope’s John Caldigate. The historic period of the novel (Dispossession is set in the 1870s), and my interest in older types of mise-en-page, meant that Duval’s drawings kept on popping up when I was researching a whole range of topics. She was a stage performer, as well as a cartoonist.

Of course, I had heard comics scholar Roger Sabin mention her in relation to the earlier history of the popular character Ally Sloper (Duval was the artist who visually developed Sloper’s world, as well as his character, although she wasn’t the first to visualize him). The more I looked, the more compelling Duval’s work and life became for me. Eventually, I teamed up with Roger and performer and scholar Julian Waite. We created a free online image archive of all of Duval’s known work (some 1400 drawings which can be accessed via www.marieduval.org), and produced an exhibition which has toured to Berlin and London and will be in Manhattan at the Society of Illustrators in early 2020.

Alongside this, we’ve published a picture book of her work and have just finished writing a scholarly book, to be published by Manchester University Press later this year. We’ve been very busy looking at, thinking about, and promoting Duval’s work. We are still fascinated and delighted by it and just as fascinated and delighted to start to build an account of her life on stage and page in the 1870s and 1880s: we describe her as a vulgar, trouser-wearing, French-speaking, home-wrecking mother. All of these things are true. Her cut-loose drawing style and theatrical cross-dressing even inspired me to undertake a reckless historiography of her work. In Chetham’s Library, Manchester, I discovered some drawings made by her under a male pseudonym. This discovery prompted me to make a new book of drawings considering what and how Duval would draw if she was revived in Manchester today. My album Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval is the result.

Turning now to your Parables of Care project, I wondered if you could give us a quick overview of the notion of "graphic medicine", and what first engaged you with that topic?

Turning now to your Parables of Care project, I wondered if you could give us a quick overview of the notion of "graphic medicine", and what first engaged you with that topic?

Graphic medicine is a term coined by Dr. Iain Williams over a decade ago. It is an umbrella term that has come to encompass three broad areas of work in which comics, drawing and health overlap: autobiography, therapy and pedagogy. The first, autobiography, is the showing of personal stories of health and healthcare by artists. The second, therapy, is the instrumental use of the comics register to effect changes in health. Third, pedagogy, is the instrumental use of the comics register to teach (and in some cases discover and teach) best practices in health care, whether personal or institutional.

The simultaneous development of these three areas of work is a great strength of the genre of graphic medicine, because it has encouraged both rigor and interdisciplinary working. For example, autobiographic work has impacted the ways in which health care institutions have adopted more patient-centered practices. Exploiting the affective possibilities of comics has provided new insights into the experiences of patients who face conventional communications challenges.

How did you plan and eventually execute Parables of Care? You worked with stories supplied by actual carers of dementia sufferers. How did you find that experience, and have you had feedback from people whose stories were eventually transformed into comics?

How did you plan and eventually execute Parables of Care? You worked with stories supplied by actual carers of dementia sufferers. How did you find that experience, and have you had feedback from people whose stories were eventually transformed into comics?

As I commented in The Elder magazine last year: “Comics can deal with serious issues in a way that is engaging, where the seriousness itself is rendered less problematic by the form. Information conveyed through visual storytelling is immediately more effective and memorable than text alone.”

I drew Parables and edited it with comics scholars Ernesto Priego and Peter Wilkins. It is adapted from a dataset of over 100 case studies available at http://carenshare.city.ac.uk. Its objective was to embrace the communicative affordances of graphic storytelling in general and specifically the emerging genre of graphic medicine. In particular, Parables explored the potential of comics to enhance the impact of dementia care research. The central challenge to the project was the development of a correspondence between the data (stories told by carers) and the drawing style and mise-en-scène of the comic. It was met by recognizing that the data already took the form of parables – stories with multiple pedagogic correspondences to unforeseen real-world situations. This further facilitated the development of the comic form, in that the parable has analogies in an existing genre – the Japanese manga ‘yonkoma’ strip, which always comprises four panels and strictly allocates types of action to each. ‘Yonkoma’ strips are also characterized by a profound ambiguity, pushing reader experiences to the point of incomprehensibility whilst remaining coherent.

This type of experience, of ambiguity underpinned by an unknown reality, corresponded precisely to the tone of the data. Recently, its international impact has grown with publication of a German translation by Andrea Hacker at the University of Bern and a forthcoming Spanish translation. Readers’ testimonials from the project blog, and examples of research communication, are included as supplementary evidence. Readers’ reactions to the novel approach are clearly positive, often including surprise at its effectiveness. Though many are from family carers, the majority are from professionals who recognize its value. Formal communication of results includes academic conference presentations to specialists in graphic medicine, and more mainstream ones to schools of nursing. The graphic narrative form of the research outputs exploits the affective capacities of the comics medium. The project demonstrates the benefits of adopting interdisciplinary methods (drawing, narrative, data capture and analysis) when researching the ecology of healthcare.

You can find out more about Simon at www.kartoonkings.com, http://www.simongrennan.com/, and https://chester.academia.edu/SimonGrennan.