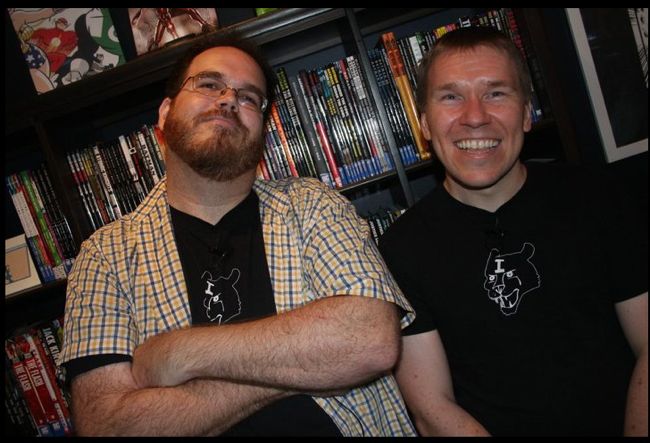

Mike Dawson was born in Scotland in 1975, and then lived in England until he was eleven years old. He moved with his family to New Jersey for middle school, a time of awkward transition for anyone, much less an immigrant. Intentionally or not, his comics have always been suffused with that sense of awkwardness, filled with characters attempting to negotiate hierarchies and social structures. In many respects, Dawson's life story and career is a familiar one for an American and a cartoonist: living the immigrant experience, doing his own comics as a teen, grinding out a daily college newspaper strip, drawing his own mini-comics, attending shows like SPX, receiving enough feedback to keep going, collaborating on his own series, getting a big deal from a major publisher but not receiving a shot at a follow-up book, retreating back into the world of alt-comics, doing a web series, and going back to his mini-comics roots. Community, family, and friendship are all important aspects of Dawson's comics as he frequently explores dysfunctional versions of all three. They also reflect his own life, as he's collaborated with fellow artists for nearly his entire career. From his early minicomics with Gary Gretsky to his college days with Marissa Giannullo and his work with Chris Radtke, Dawson either published with or directly collaborated with others all the time. While his comics are strictly a solo concern these days, he continues to collaborate on a form of self-expression with cartoonist Alex Robinson for their popular The Ink Panthers Show podcast.

Dawson is perhaps best known for his memoir Freddie and Me, a meditation on memory and family that traces the history of his fandom of the band Queen through a narrative structured after the song "Bohemian Rhapsody". This was his major-publisher book and the first time he worked with an editor. Small-press fans may also recall his collaboration with Radtke, the slacker/geek series Gabagool!, which Dawson drew and co-wrote. There was also a super-hero pastiche from AdHouse called Ace-Face: The Mod With The Metal Arms. His new book, Troop 142, debuts at SPX 2011 from the publisher Secret Acres. It's based partly on Dawson's own experiences and tells the story of a troop of Boy Scouts and their fathers during a particular summer in the 1990s.

Dawson is articulate, open, and honest about his process and history as an artist. He has a natural curiosity about art and artists that makes him an effective interviewer (as any listener of his TCJ Talkies podcast can attest), and it's to his credit that he never shies away from the light of self-examination either. His willingness to put himself out there is one of my favorite aspects of his work, both as a cartoonist and a podcaster. Much as I expected, he was forthright and expansive about a number of difficult topics, including a particular collaboration that soured, and I thank him for his time.

Family Background

TCJ: What was it like to move here as a child? How long did it take for you to consider yourself an American?

MIKE DAWSON: We moved from England to New Jersey in December of 1986. I went into 5th grade. I had an English accent, which I lost within four or five years. By the time I got to high school it was gone.

People say it’s a shame to have lost it, but I was too young for it to sound “cool.” I sounded like Oliver Twist. And middle school is not a good time to be different.

I’ve always felt British. My parents are still very connected to it. When I visit, we spend a lot of time discussing England and our immigration experience. My Dad especially. We will sit and have conversations about British history and politics, as well as my parents' lives in England and how they grew up and met and started a family and all of that.

At the same time, I feel very American. This is the country where I really grew up. I feel very connected to it. I finally became a citizen this past year, which was a big deal to me.

TCJ: It’s interesting that you have this dual identity. Do you think you have a stronger nationalist identity due to the fact that you’ve had to explicitly think about and make a choice regarding this issue in a way that life-long citizens of a country don’t? Did you feel a twinge of regret when you renounced your British citizenship?

TCJ: It’s interesting that you have this dual identity. Do you think you have a stronger nationalist identity due to the fact that you’ve had to explicitly think about and make a choice regarding this issue in a way that life-long citizens of a country don’t? Did you feel a twinge of regret when you renounced your British citizenship?

MD: Yes, having made a conscious decision to become American has resulted in me having stronger feelings about the country. I didn’t have to naturalize. Nobody else in my family did. I had twenty-something years to think about it, and then finally decided it was something important to do.

I think a cynic would say something along the lines of me getting on board with America just as the country is in decline. I’m not sure how I feel about decline or not, but my general attitude is that yes, there are issues with the country - big ones - but there’s also so much that’s decent about the US, I almost felt more compelled to become an American now.

TCJ: I know you read the usual suspects in British comics growing up. Did you also read European comics like Tintin or Asterix?

MD: No Tintin, but a little bit of Asterix. The best quality comics I read were probably Oor' Wullie and The Broons, which my Scottish Grandmother would give me.

TCJ: What were those like?

MD: The name “Oor’ Wullie” means “Our Wullie,” and “Wullie” is the Scottish way of saying “Willie,” or “William.” It means, “Our William.” The Broons was a comic about a large Scottish family called the Browns.

I didn’t know it as a kid, but both comics were apparently done by the same cartoonist. They were both wonderfully drawn. I think naturalistic is a way to describe the style. They weren’t done in the common grotesque sort of humor style you’d see in a lot of British comics, like The Beano.

I assume that the comics that I read were collections of older comics that had been published in the '40s, '50s, and '60s. I think of them now reflecting British society during the war and the post-war years. The characters live modest lives, and don’t have a lot of money. Oor’ Wullie was sort of a Dennis the Menace figure, always getting into trouble in the neighborhood. He was known for sitting on a bucket. The Broons seemed to be a comic about a big lower middle-class family. Something I always thought was fun about these strips was the heavy Scottish dialect used throughout.

Most of the comics I read as a little kid were not of great quality. The Beano, The Dandy, Whizzer & Chips. One called Oink!, which was a favorite. A horror comic called Scream! I didn’t read many of the adventure comics, like Dan Dare or 2000AD. I collected The Transformers comic, which was a weekly magazine published by Marvel UK. The interesting thing about the British incarnation of [this] series was that it was different than the US one. It wasn't American imports, it was original comics made in England. However, the series would run back-up features, and these were imported American Marvel comics. And they were unusual choices. Two that made a big impression on me were the Barry Windsor-Smith Machine Man limited series (the one set in a dystopian future), and the Mike Mignola Rocket Racoon comics. I read and re-read these many times.

TCJ: Those comics were unusual for Marvel and weren’t their typical fare. What made the greatest impression on you about them? The expressionist style?

MD: I’m not sure. I think they’re both good comics, as much as I can remember them. And I probably liked Barry Windsor-Smith's and Mike Mignola’s drawing styles very much. They’re both great cartoonists. They both make a much greater impression than the more run-of-the-mill artists on the other comics I was reading. I couldn’t tell you who drew Transformers. Barry Windsor-Smith, especially, was probably the first example of a cartoonist who I could recognize by his drawings. His are easy to pick out, it’s true. But it may be one of the first examples of me thinking about the person behind the comic.

TCJ: Did your parents encourage reading comics?

MD: I don't think they ever had strong feelings about comics prior to me becoming interested in them. I think a lot of kids read stuff like The Beano, and then as I got older, and was getting more serious about The Transformers and beyond that, they seemed perfectly fine with it. I don't recall receiving comics, except sometimes as Christmas gifts. Most of the time I bought them myself with my allowance.

My parents themselves have never seemed to have a personal history with comics. I’m not sure comics have ever really been a serious part of British culture. There is a much richer history in America.

TCJ: Why do you think that is?

MD: I once had an interesting discussion with the French publisher of Freddie & Me about this very thing. We were at Angoulême, and there were a handful of British cartoonists present, but not very many. We were talking about how there doesn’t seem to be this rich history and cartooning tradition in the UK, while right next door in France, it’s a totally different story. My publisher’s theory was interesting - he suggested that it had to do with the religion that shaped the society. The more Catholic countries had a richer visual tradition, while the more Protestant ones, like England, didn’t - though they have an incredibly rich history of writing and writers. Just no comics. He said American comics were Jewish - neither Catholic or Protestant. I am not sure how well the theory holds up to close scrutiny, but I have always thought it was an interesting idea.

With few exceptions, it seems to me that most British comics fell into the category of childish slapstick, like The Beano, or boys' adventure type comics, like Dan Dare, Eagle, and 2000AD. I see connections between the sensibilities of comics like The Beano and a kind of working class vaudevillian British comedy, like Benny Hill, or the sort of shows you’d see in Blackpool. Maybe? Kind of a crass, goofy, and unsophisticated sort of comedy. I don’t know.

Either way, I don’t think there were ever a lot of English comics that were not aimed at children. It’s sort of the same here in the US, except maybe the creators working here had more ambition to push comics further. Along the way, some of them were able to take juvenile material and make something worthwhile. Maybe there just was never a British Jack Kirby. I’m happy to be proven wrong on this. This is just my impression.

TCJ: Did you have friends who read comics? Did that change when you reached the US?

MD: I always had friends who were passionate about comics. In England, my friends were as interested in Transformers as I was. They also introduced me to the mainstream Marvel universe. One of them had imported copies of stories from the Secret Wars series.

In America I soon found a new little gang of nerds, and we all read Marvel comics. Mostly X-books: X-Men, X-Factor, Excalibur, The New Mutants. "The Mutant Massacre", "Fall of the Mutants", "Inferno", "Acts of Vengeance". Chris Claremont, John Byrne, Rick Leonardi, Walt Simonson, Alan Davis, Art Adams.

I read Marvel up through high school, but slowed down on keeping it a weekly habit. At some point I "expanded" my horizons to include some DC. Around that time my friends and I got into [the card game] Magic: The Gathering, an expensive habit, the cost of which would have competed with comics for my dollar.

In college I had no money, so I only got comics sporadically. The last Marvel event I read was the "Age of Apocalypse" storyline, which I borrowed from another comics fan in the dorm. Around this time I finally started reading non-superhero books, starting with Dork!, Action Girl, Slutburger, Eightball, and Peepshow.

TCJ: How old were you when you started drawing? Were you encouraged in this pursuit by your parents?

MD: I've been drawing since I can remember, and my parents were always very encouraging. I was writing and drawing my own illustrated stories from about 7 or 8 years old. Usually horror stuff, but also some Transformers rip-offs.

My siblings never drew, but my friends did. We were putting together our own book of humorous essays, jokes, and comics right before I moved to America. It was called "The Complete Moron's Guide to Being a Moron". I continued writing and drawing comics with my friends in America. We all had our own "guys," and would get together to work on stories with them. My guy was Ace-Face. In high school and early college is when I first began self-publishing.

TCJ: In Freddie & Me, you talk a bit about taking art in high school and actually learning some useful skills, like perspective. You were an art major at Rutgers; did you similarly learn useful skills there as a painter?

MD: I took lots of art classes in high school, mostly with one teacher who was very good and extremely encouraging of the kids in her class. She makes a cameo in Freddie & Me.

Somehow by senior year I had enough elective courses saved up that I was able to take two art classes, crafts, and a drama class, all in the same day. With gym and English classes, I had such an easy and pleasurable day. With exception of a math analysis class that I just couldn’t get out of. That stupid class totally ruined an otherwise perfect schedule. I was really happy senior year. School was easy, I had a girlfriend and a car. I always remember thinking at one point how content I felt right then.

I have mixed feelings about art school. On the one hand, I was not an engaged student. I phoned in a lot of my assignments. On the other hand, I put a lot of effort into extra-curricular things, like drawing a daily strip for the school paper for three or four years, as well as doing a lot of theater. I published my own ‘zines and minicomics the entire time I was at college. I was interested in working hard on creative endeavors.

I got a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree with a focus on painting, and have not picked up a paintbrush or tube of acrylic paint since I graduated. In school, I only wanted to make comics. I picked painting as my focus, because cartooning was not an option. I squeezed comics into all of my painting assignments. For our senior thesis we had to create a piece for a group art show. Mine was a stack of mini-comics, with some shitty dashed-off paintings hanging on the wall behind them. I spent months on the comic, and probably an afternoon on the paintings.

We frequently discuss on Ink Panthers what a waste art school was. I know Alex feels more strongly about this than I do. I often gripe that I was taught almost nothing in the way of technique or practical craft. All of the focus of our classes seemed to be on the concepts behind our art, and not as much on the nuts and bolts of creating images and making sculptures. Very little focus on craft.

However, while it's a lot less tangible and difficult to measure, I have to admit college was good for improving my critical thinking skills. I became better at analyzing and discussing art. Talking knowledgeably about things. I do think these intangible skills have ended up helping me a lot in life.

TCJ: What aspects of college in particular improved your critical thinking skills?

MD: With the exception of some foundation classes, and some life-drawing classes, the majority of the art courses I took focused on analysis and critical thinking. Like, take my painting classes. The assignments would invariably be to deal with a concept or an idea. The critiques would be us presenting and defending our take on whatever idea or concept. Most of the discussion focused on whether or not the work successfully dealt with the concept. Very little of it was a discussion about the technique or craft of the painting. It was more about making the case for the meaning of the piece.

This is what I mean about developing critical thinking skills. Through group critiques, you’d learn to present and defend your own work, but also to speak semi-coherently about your classmates work. Buzzwords I recall from the time: Deconstructing. Appropriating. We said those a lot.

TCJ: What was college life like for you?

MD: Rutgers University is comprised of several smaller schools, and I was enrolled at Mason Gross School of the Arts. My first one or two years of college, Mason Gross didn't have its own campus, so we would share buildings with the other schools. My sophomore or junior year, they opened a brand new building in downtown New Brunswick, which was just for Mason Gross. It was a nice building with a lot of good facilities, and private studios for the senior students.

I made a lot of comics in college. I was publishing minicomics and drawing a daily newspaper strip. I was submitting my comics to publishers like Slave Labor Graphics, Fantagraphics, and Drawn & Quarterly. My comics were awful, but I kept going with them, because I guess I didn't think they were so bad at the time.

Towards the end of college, I’d picked up a serious comics reading habit once again, though I had very vocally moved away from reading mainstream Marvel & DC comics. I say vocal because it was something I felt very strongly about. The crappy paintings I mentioned making as part of my senior thesis were all about how comics were just as valid an art form as any other. I got a job in the local comics store and became very opinionated about what comics were worthwhile and what was garbage.

TCJ: Were you opinionated with customers or co-workers, or both? What kind of reactions did this behavior elicit?

MD : Mostly customers. I can’t imagine I was getting in people’s faces about their choices, but I would make a point of steering people to the alternative section of the store, and talking about how something like Action Girl was head and shoulders above anything published by Marvel and DC. I would get worked up about pop culture in those days. For an art assignment one time, I made a little book all about my anger over the decision to cast Arnold Schwarzenegger in the role of Mr Freeze in the Batman and Robin movie, instead of Patrick Stewart who was the obvious choice! I would get very worked up about that kind of thing.

The funny thing is, while I was buying (and enjoying) comics like Eightball and Palookaville, when I worked in the basement of the comics store, organizing back-issues, I would sit and read Youngblood and Spawn.

TCJ: What did you get out of reading those comics?

MD: Not a lot. They were just quick, easy reads. Dumb entertainment. Like junk food. No calories. But, I’ll just always have a soft spot for that sort of stuff. I loved it so much growing up.

That whole thing, being vocal about the worth of comics, being all opinionated about it, I think it was just a phase I needed to pass through. Maybe it came on as part of my own transition from a consumer of mainstream comics to a creator with aspirations of making something that felt more worthwhile to me.

I remember a few years back, at MoCCA, I was on a "Promising New Talent" type panel. The first question was along the lines of “why do comics,” and I had to answer first. I said some of the usual stuff like, “Oh, you can do anything with comics, you aren’t limited by any budget, the only limit is your imagination,” and so on. Very Team Comics, get on board sort of thing. Then some other people spoke, including Sammy Harkham, who was very articulate. While they were talking, I thought about my answer a bit, and then spoke up asking to withdraw my original statement. Because it’s a bunch of BS.

I didn’t get into comics for any of those reasons. I never sat down and thought, “Well, which medium has the greatest potential for self-expression, and which one has no budget constraints, and is only limited by the scope of my imagination? Ah, comics. That’s what I’ll do!” No, I was just always making comics. It’s just always been the thing I’ve wanted to do.

Early Comics

TCJ: What were your first published comics?

MD: I’m pretty sure my first proper minicomic was published when I was a freshman in college, in 1994. I was making comics all throughout high school, passing them around to friends, but college was the first time I went down to a Kinko's and learned how to put together a self-published book and print up a batch, with the hopes of selling them for a dollar each.

This comic was an anthology called Temporal Darkness Presents, and featured Ace-Face comics by me, and other work by my friend Gary [Gretsky]. We published five issues of this series. At some point I felt like I wanted more control over the entire thing, so I started my own title, called Fantastic Face Comics. These still had Ace-Face stories inside, but also short standalone comics that were quirkier, and felt a little more like "alternative" cartoons.

I have to emphasize, these comics were terrible. I was publishing garbage. But I fell in love with the process. I loved putting things together at Kinko's, trading with other 'zine and comic makers, and traveling to shows like SPX to try to sell things and meet other cartoonists.

I don't really know if 'zine culture was cresting at that moment, but to me it felt like it was. I loved reading Factsheet 5 and ordering stuff in the mail. There were a lot of people at Rutgers, especially in the punk community, who were making 'zines. I myself was never ever “punk,” but through a high school friend named Matt who was very connected to that scene, I feel like I floated just outside the periphery. Matt and I published a 'zine together, called Tear Down Babylon. He contributed essays, poems, and collage art, and I mostly put in comics. I had a character called the Target, who was a college student vigilante, who had broken up with his high school girlfriend, and was totally dark and moody about it, and took it out on street thugs. This character got resurrected in the AdHouse Ace-Face collection.

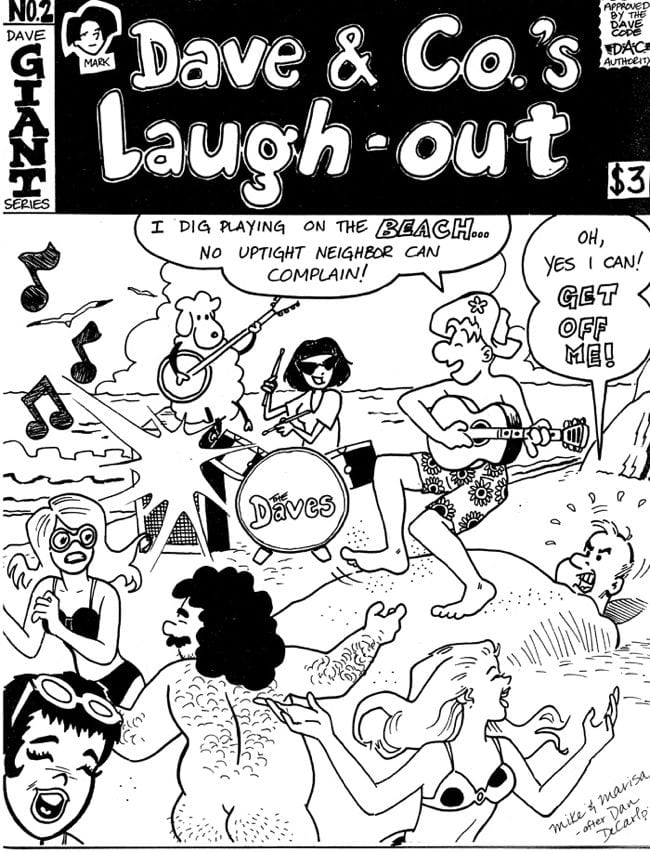

TCJ: What did you learn from doing your student strip (Dave & Co.) at Rutgers? What kind of response did you get?

MD: I drew a strip in The Daily Targum for at least three, maybe four, years, starting in 1995. At first it was called Dave & Pissa, and I drew it with another Mason Gross student. Her name was Melissa MacAlpin. That incarnation wasn't very collaborative - we'd occasionally write together, but mostly we just took turns making the strip. Alternating made it easier to maintain a daily schedule.

Melissa stopped working on it with me after the first year. I changed the name of the strip to Dave & Co. and started collaborating on it with my then girlfriend, Marisa [Giannullo]. Dave & Pissa was funny, but but very non-sequitur. With Dave & Co. we put more effort into creating well-rounded characters, and went more for situational humor.

This was all in the early days of email. I never got a huge response from other students. Dave & Pissa got a couple letters of hate-mail, probably because all of the non sequitur-ness of it. I don’t remember Dave & Co. getting as much hate-mail, and it actually got one or two fan letters. Never a lot though.

Probably most students who were at Rutgers at the time I was doing the strip might vaguely remember the comic, and probably recall there was a character in it called Porn-Star Ron, who was a cuddly benign version of Ron Jeremy.

TCJ: What was the division of labor on Dave & Co.? Did you enjoy working on the strip with another artist?

MD: There were some periods when I was working on the comic without Marisa, but I mostly think of it as something we created together. Our run started sometime sometime in 1996, maybe, and went on until 1998 or 1999, possibly? I’m really bad with dates, it seems. I can’t remember what year Marisa and I broke up, even though it was one of those big deal breakups.

We wrote all of the strips together, and divided the drawing duties. The main character, Dave, was drawn by me, and his friend April was drawn by Marisa. When Marisa and I split up, the April character exited the story and I did the strip by myself from then on.

The strip became much more mopey and morose around that time. I changed the name of the strip again, to Dave’s Family. The storyline became about the Dave character moving back in with his parents. Lots of the strips were about him feeling depressed, and at a loss about what to do with his life, which was pretty much where I was at the time, having graduated art school, living back at home, and having no idea what the next step should be.

TCJ: Were you still doing the strip after you graduated, or did you move back in with your parents during your senior year?

MD: I continued to draw the strip after I graduated. Marisa and I lived together for a period of time, and we still did the strip until we broke up, and then I worked on it from my parents' house. The funny thing is that in those olden days, I didn’t scan the strip and send it in digitally. I had to drive up once a week from the Jersey Shore to New Brunswick, to drop off my originals.

The whole time Marisa and I were doing the strip, we'd collect them up every semester and make a minicomic. Marisa was really into the cartoonist Dan DeCarlo, so most of the covers for the minis were parodies of Archie covers. We’d trade with people through the mail. We never actually bought a table at a convention, but we'd go to small-press shows. We’d buy lots of minis and attend a bunch of panels. We went down to SPX in Maryland, in ‘97 or ‘98. I remember getting minicomics from a young Kevin Huizenga. Marisa and I flew to APE around that time too, which was the first time I ever met Alex Robinson and Tony Consiglio.

TCJ: Were you familiar with Robinson's Box Office Poison and Consiglio's Double-Cross at the time you met them?

MD: I had read Box Office Poison. It was another comic I’d come across while working in the basement of that comic store. Alex was perhaps ten issues into the run when I first met him. I liked it, but I didn’t talk to Alex much at that APE.

I talked to Tony a lot more. I bought a few of his Double-Cross minis the first day, then came back and bought the rest the next morning. I gave him some of my minis and we struck up an occasional correspondence through the mail after that. Sending each other letters and drawings and comics.

I didn’t get friendly with Alex and Tony for a while, but ran into them in New York City a couple times. I went to a book signing for the Bizarro Comics book that DC published back in 2001 with a Who’s Who of indie cartoonist types, and saw Tony again. He invited me to dinner with him and Alex. We hung out regularly for a while, and then Tony moved to Indiana, while Alex and I and our respective girlfriends started socializing a lot.

(continued)