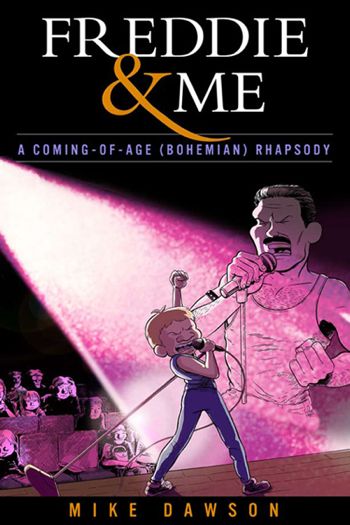

Freddie & Me

Freddie & Me

TCJ: Looking back, what parts of the book work best in your mind?

MD: My favorite parts are the "GUITAR SOLO" interlude, and then the high school section. I also think the first section of the book, depicting my family’s life in England, works well. It’s the least meandering story in my mind, as it all builds towards the decision to move to America. The third section, when I am an adult, was the trickiest section of the book. It was important, because it was all of the stuff that had compelled me to write the story in the first place, but it was harder to write about things that weren’t so far in the past. Much tougher to have a sense of perspective on it.

TCJ: What were you going for in the high school section? Was any of this taken directly from an old journal or diary?

MD: Freddie & Me is a comics adaptation of "Bohemian Rhapsody". The middle section of the song is where all of the opera singing is. It’s very melodramatic. I always thought it was very funny to have this part of the book be the part of the story where I’m a teenager. Lots of melodrama there.

1991-1992 was a period where I felt very connected to Queen. They had risen in the popular consciousness for a few reasons: "Bohemian Rhapsody" was featured in the movie Wayne’s World and had become a hit on the radio again. Then Freddie Mercury died of AIDS. Meanwhile, I’m 15-16 years old, full of angst, and at that age which is all about constructing an identity.

Both things - Wayne’s World and Freddie Mercury’s death - were like catnip to an attention-seeking teenager. The first thing - "Bohemian Rhapsody" getting played on Z100 all the time - was my first opportunity to present myself as a “real” fan of something. Someone who was in-the-know far before any of these fair-weather fans jumped on the bandwagon. The second, while something that legitimately upset me, also turned out to be a great way to build an identity amongst my peers. Mike: the guy who loves Queen so much, he gets weepy at parties when "Bohemian Rhapsody" gets played. It became part of my persona. Something I was “known” for, and received attention for.

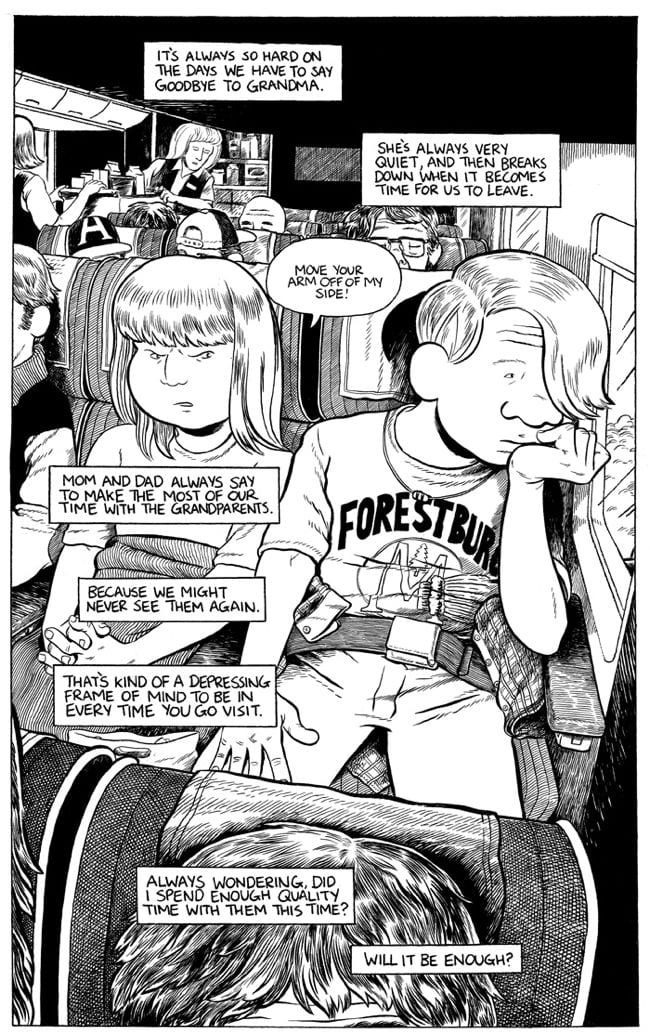

There is a difference between the first section of the book and the high school material, which was, yes, that I had kept a diary and was able to use it to make the comics. I liked how this gave the sections a different feeling from one-another. Part one has no first-person narrative, and is presented very simply as the strung together memories of a little boy. Part two introduces the inner monologue, and is more self-absorbed. Again, matching the structure of the song, where the parts all feel different from each other.

TCJ: The structure of the book is very interesting. You hit on the book's true themes in your interludes, wherein you discuss how important memory is to you, because memory and identity were the same thing for you. Is this still true? How do you manage to hold on to your memories now as a new father? Do you still keep a journal?

MD: Memory and identity were important to me when I was writing Freddie & Me. I am not sure how I feel about it now. Nostalgia is a form of sadness. I’d prefer not to be a nostalgic person. It’s hard to avoid sometimes, though.

In terms of preserving memories, the amount of material I have that covers the most recent ten years of my life far outweighs the amount I have covering the first twenty-five. I don’t keep an actual journal, but there are more than enough other ways in which I’ve created a record of things. Message boards, Facebook, Twitter, e-mail. I was recently working on a story set in 2002, and I used printouts I made of my work e-mails at the time for reference. There’s old blog entries. I’ve owned mikedawsoncomics.com for over ten years now, so there are older versions of it I could go back and look at. Plus, now I carry an iPhone with me everywhere I go. It’s filled with photos of me and my wife and daughter. Her whole life is practically documented on it.

TCJ: Back to the book's structure. The first act, childhood, really hit on the raw immediacy of memories and what details stick in our mind, like the soup you ate at a very important dinner relating to your father moving your family to America. The second act, connected to the most bombastic section of "Bohemian Rhapsody", is high school, with one's own narrative writ large. The third act in some ways was the trickiest--what were you going for in the more sedate, modern-day account of more recent events?

MD: As I said, this section of the book was the hardest. I had less perspective on it. I was writing about events that were only a few years in the past. But my entire goal for the book was to try to create meaning for the reader in that final scene where I am at [the stage musical] We Will Rock You in London with my Mother. It was an emotionally significant moment in my life, and I wanted to bring readers along to that same place with me.

I wanted to do the same thing with the final scene, where my sister shakes hands with George Michael. I wanted to make a small moment feel important, by taking readers through the entire history of my sister’s connection to the music.

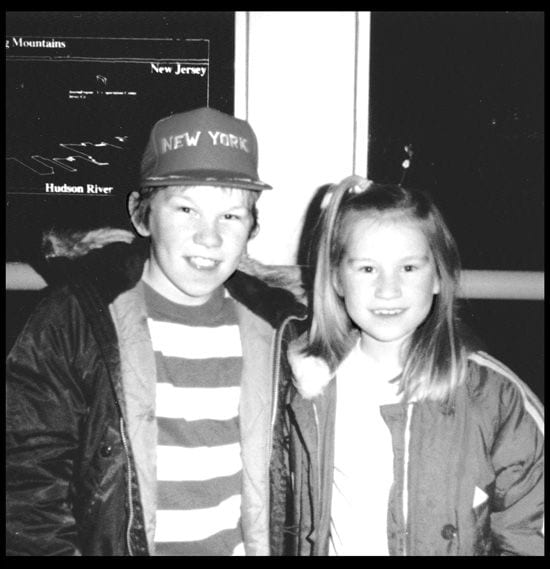

TCJ: This seemed to be a key relationship in the story. How much closer did your moving to America draw you together?

MD: Yes, I think the book is in many respects about the relationship between my sister and I. We were always close, because of the small age difference between us. And moving to America at that age, I think we had similar experiences. The book was really supposed to be about me and my grandmother, but it turned out that my grandma didn’t appear in it that much after all. It really started to be more about my sister and I, and the experiences we’d gone through.

TCJ: Were you at all frustrated at some of the response the book got, in terms of readers glossing over the themes of memory in favor of fandom (which is almost a McGuffin in some respects)?

MD: I’ve certainly fretted that the gimmick of the book may have swallowed the story I was trying to tell. There are certainly plenty of people who seem to have come at the book as Queen fans first. I get my share of letters from people talking about their own relationship to the band. But on the other hand, one of the themes of the book is about people connecting to one another in different ways. A recurring theme is my own feeling of connection to the members of Queen through their music. So the fact that people then feel connected to me through my book is amazing.

One thing that’s sort of amusing about it is that as far as hardcore Queen fans go, I really fall short. They have albums I don’t like. There are some newer albums I’ve never even heard. The stuff with Paul Rodgers, I’m not really interested. I am a big fan, yes, but there are many levels of "fanatic" and "obsessive" above me.

It’s kind of funny. While I was still working on the book, I’d originally intended not to have a picture of Freddie Mercury on the cover. The publishers really encouraged me to change my mind on that, because, obviously the book is going to appeal to a Queen fan if he or she sees a drawing of Freddie Mercury on the front cover. And, somewhere in between that point and when the book was out, I totally got on board with pushing the Queen-fandom angle myself. I reached out to Queen fan-sites, I befriended everyone on MySpace who had a picture of Freddie Mercury as their profile picture. I made plans to go to a big North American Queen convention, to speak to the fans and do a presentation and sign some books.

All of those things would have been fine ways to sell some copies. But I sort of had to forget about the fact that it wasn’t really a book about Queen at all. It’s about me and my family. And there’s no reason a Queen fan is going to be more interested in that story than anyone else. I guess I just wanted to move some books, though.

TCJ: You worked with an editor on this book. What was that process like?

MD: It was OK. Not the worst experience, but definitely something I learned from.

The book was bought by two publishers, Bloomsbury USA here in America, and Jonathan Cape in the UK. I worked with Jonathan Cape a little bit - mainly on copy editing and grammar - but my main editor was at Bloomsbury. This was the person who read through the manuscript, and sat down with me with suggestions for changes. These ranged from adding new scenes, to taking some material out, to rearranging the order of some sequences.

The book was in a close to final state by the time I started dealing with an editor. Fully inked and finished pages. Not the kind of thing where I was working from a script or even thumbnails. It’s much harder to suggest changes when the book is basically done. So the edits were more like rearranging furniture in a house that was already built. This was probably frustrating to everyone except me.

Most of the changes were minor. There is one suggestion I regret taking, which is a transitional piece that comes at the beginning of the third section of the book. I wrote this little mini-essay about autobiography and comics, and talked about the other kinds of comic books I’ve done. I scanned and pasted in panels from other stories. In hindsight, this feels self-indulgent. I can’t blame the editor for making that decision, but I was prodded to write a transitional sequence. Originally, things just jumped from high school to me being an adult. In retrospect, I think it would have been fine to leave it that way.

The main thing I learned through this is that editing is OK, and even welcome, but you have to work with people who really get what you’re trying to do. Because they’ll be able to do the thing you want editors to do: which is help you tell the story in the best way possible.

TCJ: What changes did you see in your own style as a draftsman, especially from the beginning to the end of that book?

MD: I used Windsor Newton Series 7 and Raphael Sable brushes on cold-press illustration board for all of Freddie & Me. I tried this combination of brushes and boards for the first time when I started the book, and it was a revelation. It was possible to get a wider range of illustrative effects. I liked how detailed cross-hatching came out. I had a great time with it. The backgrounds and environments in Freddie & Me feel like they grew from where I’d been going with the final issue of Gabagool!

The approach was time consuming. I was able to average about two pages a week. Which is why it took me close to four years to complete. It’s not an approach I’ve been able to replicate since becoming a parent. I’ve had to economize in order to stay productive.

TCJ: Is a more involved style something you intend to return to when your daughter grows older?

MD: No, I think it’s been a step forward actually. I think the drawings in Troop 142 are better than what I’d been doing before. It’s possible that the time-constraints caused by having a family forced me to pare down in a way that was an improvement. It’s less fussy and fiddled over. Much cleaner, more consistent, and pleasant to read.

TCJ: How did you get the book published? Did you hire an agent?

MD: I had written the first two sections of the book when Chris Pitzer at AdHouse agreed to publish it. This was thrilling. It was what I had been working towards. We never signed a contract, however.

At the time, roughly 2005-2006, I was working at eScholastic, producing websites for Scholastic’s trade books. This meant I worked with people involved in the publishing division of the company. One of those people was getting married and leaving the company, and some of us from eScholastic were invited to her going away party. At the party I got to talking to Janna Morishima, who at the time was working on Scholastic’s Graphix line of kids graphic novels. I told her about my book, and she suggested I send it to an agent she knew who was interested in representing graphic novels.

I mailed him a sample of the story and a cover letter, and received an response pretty rapidly. I went in to meet him, and he was very enthusiastic about the story, and told me how he thought it would be something Jonathan Cape in the UK might buy. And, he was right. So, I sold the British rights to Cape through him.

Since I didn’t have a contract with AdHouse, he then mailed the manuscript out to other US publishers. Bloomsbury USA and Random House both made offers, and then I signed the deal with Bloomsbury. From what I could tell, Chris Pitzer seemed all right with all of this. And, at the time, it seemed like the best decision for me. A good advance is hard to turn down.

TCJ: A quick Google search reveals that you have always been active in promoting your own work, with numerous interviews surrounding new releases. How long have you considered this to be important?

MD: I do try to get attention for my comics, yes. I also do my best to be conscious of the balancing act promoting can be. I think hyping a book is OK to a degree. It’s much harder to get buzz. There’s a difference between the two. Buzz is good, hype isn’t. If you are all hype and no buzz, then you run the risk of annoying people.

Being online feels worthwhile to me. I love Twitter. I use it to promote my work, yes, but also I love being able to talk to and form relationships with interesting people, and find work by other cartoonists that I enjoy. It’s the best of all worlds. Before Twitter, it seemed like online promotion consisted of spamming comics-related message boards. I used to promote myself on Facebook, but decided to not do that anymore. I try to keep Facebook as much about friends and family as possible.

At the end of the day, I think it’s all a learning curve. I mean, who really knows? Maybe I still hype things more than I should, but how can you tell what’s the right amount? You want people to be aware of something they may genuinely enjoy, but you also don’t want to be screaming at them 24/7 about how they should “check you out.”

Ace-Face

TCJ: The Face was one of your oldest characters. He reappeared in the AdHouse Project: Superior alt-comics anthology book. Were you invited to appear in the book or did you dust off the Face when you heard about it?

MD: I heard about Project: Superior, and then pestered Chris Pitzer into letting me into the anthology. I pitched him two short story ideas, one was Ace-Face and the other one was something called Ultra-Violet Ray, which was a jokey one-shot story. He liked the Ace-Face idea better, and agreed to include it in the book.

TCJ: What made you decide to turn Colin "Ace Face" Turney into a version of your father, down to his modern-day pony tail and job as a professor in America?

MD: Ugh, of all the choices I’ve ever made in my comics, this is the one I regret the most. It’s not supposed to be my Dad. It was just something that made me laugh - putting the pony-tail and mustache on him. It was in the story where I had introduced the idea that Ace-Face had emigrated to America, so it was like a little joke for me to have the characters resemble my parents.

It was done prior to me getting to the parts of Freddie & Me that featured the modern-day versions of my folks, and I guess I didn’t really think what the side by side comparison would seem like. Also, that story was done for the short story I did in Superior: Showcase #1 and it didn’t occur to me there might one day being a book collection with this comic in it. I’ve never given my folks a copy of the Ace-Face book, because I feel odd about that choice. Ugh, what a mess...

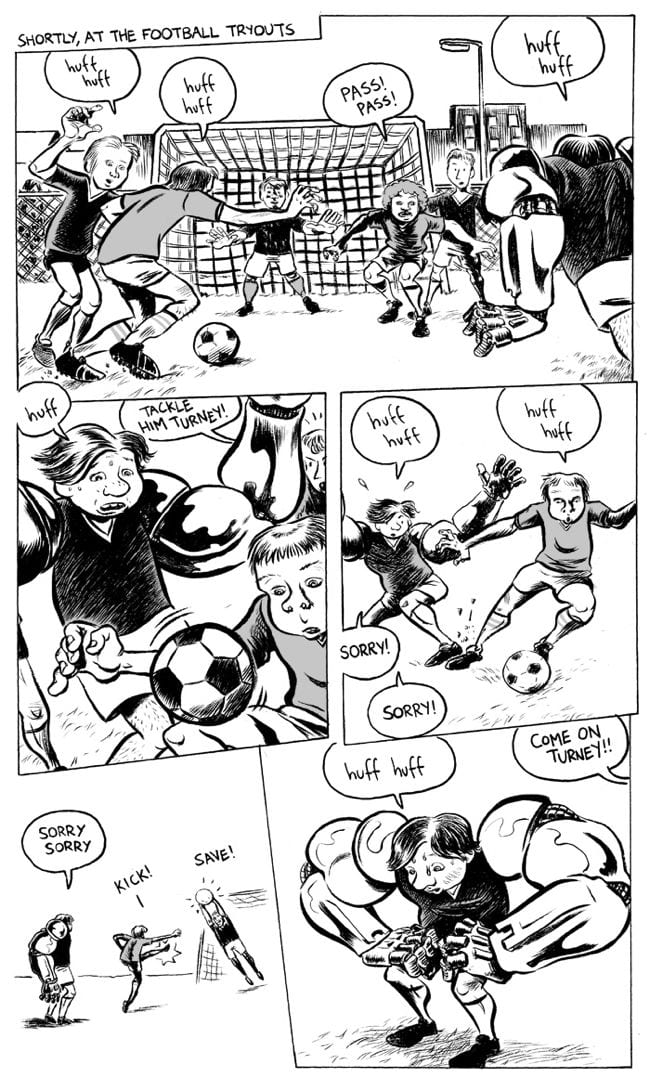

Stu Turney is definitely modeled on me, however. I drew the stories that centered on him, specifically for the Ace-Face book.

TCJ: Stu Turney’s story in this book is the same as a story you told on The Ink Panthers Show. How anxious did that incident make you? Did it cause as much friction with your wire as you depicted?

MD: Yeah, it was a distressing situation. We lived in this apartment for a couple of years before we had a baby, and during that time the incidents with drunks on the stoop were lower, but also we didn’t care as much. The time that our daughter was born coincided with an increase in the amount of incidents. I remember the first night we got back from the hospital, exhausted, trying to get some sleep, and guys being out there, right below our window, yelling and fighting, late into the night.

Maybe it sounds funny or trivial, but it wasn’t just a noise thing. These guys were aggressive: they’d get into fights, they’d harass other people on the block. They didn’t care when the police were called. And for me, it raised all sorts of feelings of insecurity in me, for not being the kind of father who could sort that kind of situation out. I’ve always been someone who can’t be in fights - I recognize this in myself - but you know... when you’re a dad, you want to be able to do all the things you think dads ought to be able to do. So, it bothered me for that reason too. This became the thing I was really interested in writing about with these stories. The idea that superhero comics idealize violence as a way to solve problems, but the reality of violence is something else entirely.

We resolved the problem by just moving out of that apartment and going somewhere nicer. On the day we left, we were packing the moving van and an old lady who lived in the building, who was related to some of these guys, said she didn’t blame us for leaving. She said she wished she could leave too. These guys kept her awake and harassed her as well. And she was probably the mother or aunt or even the grandmother of some of them. They were really just horrible people.

TCJ: Ace-Face has the trappings of being a fun, light-hearted superhero book (given the name and the title), but it quickly takes a dark turn. Did you aim for an emotionally realistic story in terms of the collateral damage a superhero might cause? In particular, the story where Ace-Face confronts campus vigilante the Target is ugly and plays out realistically in a way that is not exactly heroic. Why did you choose to intersperse an Ace-Face fight with Stu Turney agonizing over confronting the loud guys outside his apartment building?

MD: I became interested in the idea that superhero comics idealize violence as a way to solve problems, but the reality of violence is something else entirely. The story you’re talking about is the one that makes that contrast the most explicit. There’s a flashback to Ace-Face involved in some adventure, interspersed with what’s happening in the present day, with his son feeling helpless to control a situation.

The Ace-Face story with the Target deals with this as well. Real violence vs. cartoon violence. Yes, the outcome of the comic is harsh and ugly, but I did amuse myself drawing the full-page fight scene, where they’re tussling and the Target’s shirt gets yanked off. That’s one thing I’ve always noticed about real-life fights. If a t-shirt doesn’t get torn off, then at least some-one's going to have a stretched out collar or something after the fight gets pulled apart.