EC COMICS

GROTH: The first work that you did at EC would have been 1951.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Two-Fisted was first.

GROTH: So the war stories is what you started to do at EC, and that was under Harvey's editorial guidance.

SEVERIN: Well, more than editorial. This guy—he wrote the stories. He got the basic ideas for the way he wanted the book or the individual story to go. Then he would write them keeping in mind who was going to do the artwork. Then he would do all the criticism. Editing. He just did the whole damn thing. He oversaw the coloring. The whole damn shooting match.

GROTH: Let me skip back just for a second. When you started working in '51 for EC under Harvey, did you still have the Charles-William-Harvey studio in operation?

SEVERIN: Yes, we did. We sure did, because I used to collect the cover proofs, and I would hang them along the wall decorating the entry room of our studio.

GROTH: Can you describe the logistics? If you still had the studio, did that mean Harvey wasn't working in the EC offices when he was editing Frontline and Two-Fisted, or that he had both places that he could go to?

SEVERIN: Well he—

GROTH: Because he was on staff.

SEVERIN: —he did an awful lot of his work at home. He did an awful lot of work at the studio, and he would make frequent trips downtown to the EC place. [Jokingly]: I bought a nice rifle down—oh, never mind. He worked everywhere.

GROTH: Because he would technically have been an employee of EC, wouldn't he? Because he was an editor.

SEVERIN: Yes.

GROTH: But he wrote all the work in the two war books, and he drew some of the strips, of course. I'm not sure if that would have been as an employee or—

SEVERIN: You see, I don't know the business arrangement between Harvey and Bill [Gaines], but later on, after we disbanded the studio, he was up there at EC. So I assume he was in the capacity of being an employee of EC as well as being the editor. But that didn't alter anything. It just gave him another place to work.

GROTH: When Harvey got the position at EC and star fed editing and writing the war books, did he immediately approach you about drawing for him?

SEVERIN: Oh, hell's bells. We did an awful lot of talking about this stuff, even before he approached Bill Gaines.

GROTH: Oh, is that right?

SEVERIN: Yeah. You know.

GROTH: Tell me.

SEVERIN: Well, he'd talk about the job. I started getting him research for different things, especially when he got into the Civil War. I started him on the research. He wasn't aware there was such—well, like most people, they think there were gray and blue uniforms and that was sort of it. I got him started on that, and next thing you know he was contacting Fletcher Pratt and trying to find out all the minor details of all the different battles that went on. Getting back to the war stuff, we talked over some of the experiences that the guys had, which he was incorporating in the stories. Then of course, when he got the thing going, he did a lot of that with us.

GROTH: He became pretty obsessive about historical details.

SEVERIN: Yes. I didn't know what I'd gotten him started on.

GROTH: In fact, he appreciated the historical precision of your drawing very much.

SEVERIN: Well, up until the time I did one job that caused us to have a flip-out. It was about U.S. Grant. This happens with everybody. You have a period where all of a sudden everything goes to hell, and your work isn't coming out the way it should. If everyone just keeps quiet, gives the guy a week then he's back on track. Well, when I got the Grant story, I was into one of these blue mood areas and it wasn't coming out the way I would like it, and apparently it wasn't coming out the way he liked it, and I was willing to agree. I don't want to get into too many details, because I don't like the way people take it. They take it wrong.

GROTH: Well, give me as many details as you're willing.

SEVERIN: It was just that he wasn't happy with the job and for reasons that—it got to be personal on his pan, and I didn't care for that part. So we had a blow out there, and—

GROTH: This was your Grant story?

SEVERIN: I'm sure enough to say yes, but I hate to say yes and be proved wrong. You know what I mean?

GROTH: Sure.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Say it's Grant. What the hell?

GROTH: I imagine that because Harvey took the work so seriously, and he also imposed upon his own personal views of art dearly on the work that—

SEVERIN: Which he has the right to do, you know.

GROTH: I guess there would probably be a very fine line between the personal and the professional when you're in an intimate creative situation like that. So that's not surprising. Was the disagreement about a particular artistic aspect of the work?

SEVERIN: Yes. The work apparently wasn't up to snuff, and I know it wasn't. But you do your best, and it's just one of those periods where you're going through a blue fog, and there's not much you can do about it until you wear yourself right through it.

GROTH: Was that a story that you inked yourself?

SEVERIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Because he was not fond of your inking, he preferred Will Elder's inking on your work. Do you remember that?

SEVERIN: Oh, that's probably true, although he's the one who told me to ink my own work. Why he might have said that, of course, would be the obvious. Willie's inking was in keeping with what was being done in the comic field. Gradually, by—hell, he let me do my inking at EC, and it was through that that I got enough practice to get into inking. My pen line became strong enough that I was able to do some of the "American Eagle" and through both of them, of course, I got enough practice to be able to ink. I learned how to use the pen for comics, rather than the way I had been doing it. I was very light, and there weren't that many blacks as a result. I guess he wasn't happy with it. I wasn't happy with it the way it looked. The drawing was all right, but the ink line I was fidgeting this way and that way, trying to figure out how to do this inking with the pen. I couldn't do it. No excuses. I just plain couldn't do it right. And it's only through plain out-right practice that you're going to get it done. So I kind of thank God he let me do it!

GROTH: So in a way, you agree with Kurtzman 's criticism of your inking originally.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Yeah.

GROTH: If I could, maybe I could read a quote from Kurtzman about your inking and have you tell me how you react to it.

SEVERIN: I do like to shoot him, so I guess it's—

GROTH: Right. He said, "I was always fascinated by John's pencils. His drawings were so precise. Perhaps that's not the word. I mean, they were such good depictions of the real thing. I always had the feeling they got screwed up in the inking, and I took a couple stabs at inking John's work myself. I liked what I did—"

SEVERIN: Yeah, so did I.

GROTH: Did you?

SEVERIN: Yes.

GROTH: "Will's weakness was that he didn't have the sense of accuracy that John did. I don't think he had the sense of accuracy that I did, but he was a master of graphic black and white design, better than John and better than me."

SEVERIN: This is true.

GROTH: "But when John had to put ink on his drawings, he'd suddenly strike out—"

SEVERIN: [Laughs.] That's no joke. There're a couple of times I can point out. Oh boy!

GROTH: He goes on to say, "There are two elemental differences between John's and Willie's inking: accuracy of detail, which John runs circles around Willie with; and graphic clarity, which Willie runs circles around John with—"

SEVERIN: Uh-huh.

GROTH: "Willie understands priorities in graphics. He knows when a drawing should be light, and when it should be dark, and he knows how to make it light and dark. John gets confused. He stumbles all over."

SEVERIN: You're not kidding.

GROTH: So you agree with that?

SEVERIN: Absolutely, at that time.

GROTH: Now you must also feel that you eventually surmounted that problem.

SEVERIN: Yes, but only to a certain extent. I still—I think that what I had been doing wrong is a product of the way I think, and I don't think that I—I don't think that I think. [Laughs.] I don't believe that I've changed down deep. I think that anything that I have learned that is good I've tried to put into it. But it isn't as natural, and as a result, I think my stuff still could stand a lot more blacks, a lot more strengths. I won't argue with myself about the drawings (most of the time) but—well, take the cover that I did for you. I had a hell of a time making the French spread in the foreground as dark as it was! Take somebody like Willie. He would have put big blacks in that thing, and it would have stood out like a sore thumb, and it wouldn't have made me happy worth a damn because I would have missed seeing all the little details. So I still have that thinking in the back of my mind. I have to overcome it still at this day and age.

GROTH: I think what you're talking is black-and-white patterning that you have trouble—

SEVERIN: [Searching.] It's not with the patterning. I don't know how to describe it and give you an example right off the bat here.

GROTH: Because one of the things I was going to bring up is that your composition can be exquisite, I think. And it's especially true of the airplane stories in the war books. The composition and the design is just impeccable. I'm wondering how that relates to what you say is your inability to spot blacks properly.

SEVERIN: Well, an example in the airplane stories, let's say. I'll have a close up of a guy in a cockpit and there's much that's going on in the rear. I have a hard time, and the average artist in this business would have no trouble at all. He would take the guy in the foreground, and he would put lots of blacks in this thing. And the guy would stand out and then the background would drop way back where it belongs, and the pattern on the panel alone would be a definite black and a light area in contrast. Whereas, when it comes to Severin, I have to draw every damn detail of the goggle and put all the gears and everything in the right place, the mustache, whiskers, every cotton-pickin' thing. And I have a hell of a time making this area dark enough though, to witness that spread that I was just talking about in the cover that I sent to you. I have a hell of a time making it dark enough so that it gives a pattern of dark and light. I am personally interested in every part of the whole darn shooting match, and I want everybody to see all the stuff there. I don't want them to see it and know that I can draw it. It's obvious that whoever is drawing this knows what he's drawing, or is trying to, but I have a hard time blocking out some of that stuff, sacrificing the detail for a black and white pattern. I still have that problem.

GROTH: Which someone like Alex Toth doesn't seem to have.

SEVERIN: There's a—oh, wow! Yes. You struck a note. Al Toth. Wow! That man—fabulous!

GROTH: On the other hand, the story you did called "Ace" was really beautifully designed.

SEVERIN: Thank you. [Laughs.]

GROTH: I don't know if you remember "Bomb Run" but that was another one.

SEVERIN: Oh, yes. I can remember my buddies in the airplane. I used their names and everything.

GROTH: Yes. Exactly. About "Ace," Kurtzman said, “Ace was John Severin at his best. He worked with a pen. Essentially these were pen line drawings, and the design problems were at a minimum. He wasn't trying to be Jack Davis or anybody else but John Severin, and he knew his business in this particular story. He knew airplanes, and he knew movement. John has the talent of an actor, and he also understands movement in space, which is essential in making World War I airplanes move through the sky. This, to me, was one of his absolutely best stories."

SEVERIN: I wish I remembered this thing. It's awfully nice of Kurtzman to say that.

GROTH: I'll have to send you a copy. [Joking.]

SEVERIN: [Laughs.] No. No. I must have it here somewhere.

GROTH: Because it is a story you inked yourself.

SEVERIN: Yeah. I have the collection, the whole collection that was put out by Russ Cochran.

GROTH: You started doing the war stuff for Kurtzman, and Will Elder inked the first seven stories, I believe.

SEVERIN: Oh yeah?

GROTH: And then you started inking, occasionally, your own work. And this seemed to me, based on the limited amount of work I've seen of yours during this period, this seems to be a quantum leap in quality from the work you were doing at Prize. Do you have the same recollection?

SEVERIN: Good or bad?

GROTH: Good.

SEVERIN: Oh. I'm not being silly here. I'm trying to judge this guy we're talking about—me! Because that far back, it's another person. I wonder: what is the difference that you see? I can't imagine what the difference would be, except in the story line.

GROTH: Well of course the stories were better.

SEVERIN: Oh, well yeah. Even though I probably wrote some of that other stuff. [Amused.] Gee, what are you saying? [Laughs.]

GROTH: Oops.

SEVERN: Joke. Joke.

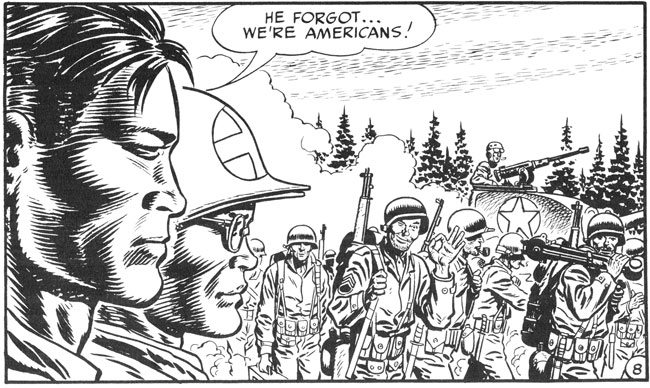

GROTH: I'm looking at the Frontline Combat #1 story you did called "Marines Retreat" and it's inked by Kurtzman.

SEVERIN: Wasn't that great!

GROTH: Yeah. It's quite beautiful.

SEVERIN: He made me look good. I wish he had done a lot more of those things. I really enjoyed that one.

GROTH: Can you tell me what you thought Harvey gave to your work that—or, can you contrast Harvey's inking with Elder's?

SEVERIN: [Pause.] There was more modeling with Elder. Harvey went right to the point with his brush. They just had two different styles. Very different. And I really liked—Listen, I must have liked Willie's work. We stuck together for a long time until it got to the point where I had to break loose and do something on my own no matter how poorly I was at it. To see Harvey suddenly—Bam!—do a job, why, that, was very exciting. I just wish that I could have done half the jobs for Harvey and the other half with Willie.

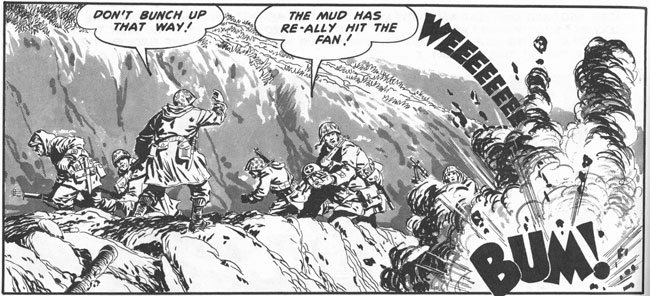

GROTH: One of the ways in which I was going to say that your work looked better in the war books over the Prize Western stuff was in the storytelling. The variations of shots, the pacing, and —

SEVERIN: We have to do one thing, there. We have to credit Kurtzman for a lot of that.

GROTH: I was going to ask you that. Did Harvey literally lay out the whole story?

SEVERIN: Literally laid out the whole story, panel by panel by panel. Our layout pages from Harvey could be compared to the original artwork of whatever artists you want to pick— Davis, Elder, me, whoever. Reed Crandall. Anybody! And they were right on the money. Right on the money. Everything was. Right down the line. You could almost print Harvey's sketches.

GROTH: Was the story lettered by the time you get it to draw?

SEVERIN: Wait a second. Let's see.

GROTH: Because I thought you were given the boards with the lettering in place.

SEVERIN: I don't think mine were. Because I might decide to put the guy on the other side of the panel—you know, that would annoy him. [Groth laughs.] Every once in awhile I would see something drastically different and I would change it. It didn't happen too often. However I do think that the lettering was put in afterwards.

GROTH: But all the panels were blocked out.

SEVERIN: Well, you don't mean on the art page itself—

GROTH: That's actually what I did mean, but that's not true?

SEVERIN: No, not for me it wasn't. If it was that way for anybody else, I didn't know about it. No. I—

GROTH: How would Harvey provide the layouts?

SEVERIN: He'd provide the layout on a separate piece of paper and you just followed his layouts, which was pretty damn easy. As a matter of fact, it's strange to look at Wally Wood and then look at Jack Davis, and I see Harvey's layouts. All these wonderful panels that these guys were doing, including myself, all these panels—these were panels coming out of Harvey's head! The technique was different, and that was put in by the artist. But the panels—these were Harvey's. This was Harvey's story. He was the cameraman. Totally.

GROTH: So the panels would be laid out on a separate sheet of paper.

SEVERIN: Yes.

GROTH: How carefully or scrupulously would the layout within each panel be blocked out?

SEVERIN: Oh, he did it very loosely, very strong lines.

GROTH: But each figure would be there?

SEVERIN: Yeah. Well, for the most part. If there was a crowd in the background, he wasn't going to draw everybody. He would indicate the crowd. But the important things were very strong and you couldn't miss it! You changed the proportions, naturally, because when he put in the layout, he—let's say it was a large head screaming in your direction, and a shoulder and an arm coming up. When you draw that head in that area, you might have your shoulder a little bit bigger. You might have to change where the elbow is out of panel so that the hand is in the right place, but that was totally unimportant. The layout was there.

GROTH: Did you consider this a great educational experience to work over Harvey's layouts?

SEVERIN: Boy, can you say that again. Wow! You're not kidding. He taught me all of the things that I know about comics and that I knew had to be put into comics. He did it with his layouts, and working on it time after time it finally got in through my thick skull. When some guy gives you a good criticism, it's very helpful. But when somebody not only gives you a good criticism but shows you in the concrete—that can't be beat. For instance, somebody could give you the theory behind Alex Toth; his reason for blacking and whiting in areas. That's swell. But when you sit down next to the guy and he shows you, that's different. Well, Harvey did more than that. He gave you the actual layouts. He added the blacks and the whites. Some of those things he even threw in just a dash of color to make damn sure he knew that was supposed to be an explosion or something. So I can't say very much about those layouts. You know what I wish: I wish I'd have saved them.

GROTH: Yes.

SEVERIN: I'd be a multi-millionaire! I'd be the publisher of The Comics Journal. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Well, now, wait a minute, you couldn't be both.

SEVERIN: No, but it would be one of my sidelines.

GROTH: If you play your cards right, you still could be the publisher of The Comics Journal. [Laughter.] Here's something else that Harvey said about you and Will Elder's inking. He said, “When John and Willie used to draw these things together, boy, l just loved the results we'd get. Because John was about the best there was in drawing World War II. And Willie—John never really appreciated Willie because Willie would hurt John's authenticity. John would draw four buttons and Willie would turn them into three and a half, and that would kill John. And yet, Willie would ink his stuff with great clarity. His stuff was very clear, and Willie, who had been through the whole scene, right in the thick of the Ardennes Offensive, I think, knew all about World War II. He got the flavor and he got the look. Not too dirty— these guys weren't really crawling in filth, but they were bearded. John and Will were a great team for this stuff. John was always fighting it, and boy, was he wrong." First of all, is it accurate that you were fighting Elder inking your work?

SEVERIN: Well, no. Yes and no. I was just going to say, before you said that last pan, that fighting it is too strong a word. I wasn't—oh, heated up. What he said was true—all of it! If Willie, in this case, would leave out a little button or something like that, I would say, “What the hell? Couldn't you put that little —"Only it wouldn't be a button. It would be something more important. Like on a machine gun, the sight would be a certain way and for Will, it didn't make any difference art-wise because it came out better the way he inked it. But I wanted that sight to be in there. And it was continual that he would do that. And if you put everything that I wanted to be put in you come to the same problem that I still have—using my blacks! If I use too many blacks, I wipe out all of that stuff. And this is where the problem was. Willie used the black in an artful way and made the picture a lot stronger. Except for the fact that "fighting" is a little strong, everything that Harvey said is pretty much true.

GROTH: If fighting is too strong a word, was there some reluctance on your part to have Elder ink your work?

SEVERIN: No, not at all. No. As a matter of fact, as far as that goes, we got along fine. Harvey suggested one time that why didn't I try to ink myself and let Willie do his own penciling for a while. So we tried it, and if you have the books you can see what a mess I made of that. And one thing I will thank him for, at least I finally got enough practice in, because of their patience, to do some work on my own. And I think it was good for Willie, too, because he ended up not just being an inker with me, but doing things on his own. So I think it worked out pretty well.

GROTH: When you started inking your own work, you started inking with a pen, if I'm not mistaken.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Once in a while I would turn out a story with a brush, but I was never happy with it.

GROTH: Was the brush more difficult for you to control?

SEVERIN: Yeah.

GROTH: Do you think that you finally did learn how to control that to your satisfaction?

SEVERIN: No.

GROTH: Or at least more satisfactorily?

SEVERIN: No, never. Unless I'm doing wash drawings, a piece of artwork where I'm using grays entirely. Then I can use a brush fine. But then it's sort of like painting. Whereas, when I'm doing comic work, and boy, I want every line in there. And the only way I can get them in there properly, as far as I can see, is to use a pen. And it was easy. I had started out using pen that it was like second nature.

GROTH: Why did you feel compelled to try to learn how to use a brush?

SEVERIN: It was just that everybody was doing it with a brush, and it was more or less expected of you, and when I first had gone around with whatever pen and ink work I had, people did look at it kind of askance and say, "Gee, you used pen on this, huh?" And I thought, maybe they don't like this. But I gradually got to the point where, due to the people up there at EC allowing me to, I felt a little more sure of myself. Why, even Stan Lee said it was OK if I used a pen. So it must have been OK!

GROTH: Here's something Kurtzman said about your pen work versus your brush work. "John's so much better just doing a pen line. I use him 'Why? Why?' in reference to using a brush, and I got the impression that he was just a crazy mad fan of Jack Davis. He wanted to ink like Jack—"

SEVERIN: Oh, why I used a brush? Yeah, that's true.

GROTH: He went on, "But Jack is a master mechanic with a brush, and John was not."

SEVERIN: Not anywhere near.

GROTH: "John is capable of great things, but I had a hard time with him. We got to the point where we were at each other's throats." First, were you in fact doing it because of your admiration for Davis?

SEVERIN: No. The reason he said that is I did one job only that I used Davis as a model. And I guess he misconstrued that I was a fan. Not that I'm not a fan. But what I'm saying is...

GROTH: But that's not why you did it?

SEVERIN: It wasn't why I did it. It was just that I was searching around. Who in the hell can I pick up here and learn to use a brush from? That was a terrible sentence. Let's go back over that. No, you do it. There were so many people in comics who just had a way of doing the same method—very boring—that Davis was rather exciting. And I could imitate him and maybe get somewhere. So I did a story. I can almost see this. It was in Two-Fisted Tales, I'm sure.

GROTH: Was it "Belts and Celts?"

SEVERIN: No, but I did use a brush on that, didn't I?

GROTH: Yes, you did.

SEVERIN: That was terrible. No, it wasn't that. This was a war story. I even did what any imitator does. I tried copying certain techniques that he would use and put them in, not many of them because I didn't come off anywhere near like Davis. But Kurtzman spotted the fact. He says, "You're trying to be Jack Davis." And I said, "Holy Moses, no!" But I sure would like to be as capable of using a brush as he is.

GROTH: When Harvey said that you and he could be at each others throats over this, what interested me is that you could have such aesthetically charged discussions about these things, which I can't imagine goes on in mainstream comics today. But these mere matters that were of great concern to both of you?

SEVERIN: Yeah. Harvey always kept trying to get the best from me. I suppose he tried to do that with everybody. He always wanted me to be able to do more. And I was plodding along, trying to learn it one, two, three. And he was of the opinion that I could jump all the way up to five and on up to eight! But if I ever got to eight or 10, it was going to be one, two, three, four—that way. And we both had rather strong characters. His point of view, by God, was his. And I think mine was the same way. I know Woody was complaining about Kurtzman being so dictatorial as far as he was concerned. He got along with Harvey in a different way than I did because he was quiet. He would listen. And he would go off in a corner and swear. Whereas, it took me about two seconds and I was already swearing. It was easier for him to get along with any problems like that. Because I would fight it immediately, right on the spot. This may have something to do with the fact that Harvey and I didn't meet as editor and artist. Our relationship went back to our teenaged years.

GROTH: You seem, based on my conversations with you, incredibly even-tempered. Have you gotten even-tempered over the years?

SEVERIN: No. I still flip out. Not as loudly as I used to because it takes more effort these days. No, I haven't changed that way. I just spoke my mind. I still do.

GROTH: I understand. Harvey must have been one of the few editors in the history of comics who had a real understanding and appreciation for the beauty of the line and the visual nuances of comics.

SEVERIN: He was much more of an artist than he was. What I mean is he should have —let's put it this way, can you imagine what the real art field would be had Kurtzman gone into finer arts? So he brought this feeling, all these inside things with him to comics. And he applied them where he could.

GROTH: Well, it's interesting. You're probably not up on comics enough to be fully aware of this, thank God, but that was a time—certainly during the EC period and within EC itself—when these kinds of questions—the quality, of the line and how appropriate the drawing was to the story, and so on, could be significant. Now that element of aesthetics in comics, in mainstream comics, at least, certainly doesn't matter at all. I mean, to talk about the quality of the brushwork or something is ridiculous given the subject matter and the general level of quality and how frivolous it is.

SEVERIN: You're right.

GROTH: One thing that occurs to me is that one of the reasons that it was important is because of the whole context. The stories were better written, and they were something that both you and Harvey, and presumably the other artists, cared about in a way that craftsmen who take pride in their work can care about them.

SEVERIN: I think that every kind of work that was being done up at EC was done with a lot more thought and care. There were one or two here and there that were trying to do something, but at EC, they were all doing it that way. They were all interested in getting a good job done, whether it was the lettering, the art, the layout, whatever. It was done with thought and care.

GROTH: Can you contrast that with your understanding of working at Prize, for example? Was there a marked difference—

SEVERIN: Oh, sure.

GROTH: —in the professional atmosphere between the two companies?

SEVERIN: Its atmosphere was almost a lack of atmosphere, which was common with most of the companies. You came in, you were hired for the work that you could do, they gave you a script, you came in with your job. You'd have to be pretty doggone messy to have gotten any kind of criticism. DC was somewhat like EC in a much broader way, much more big-time thinking. They did give you criticism. Kanigher, Kubert...were very interested in getting the job done right whether they wrote it or drew it or had it drawn.

They were interested in getting it done properly, the way they saw it.

GROTH: Was their criticism—you mentioned Kanigher for example—of an aesthetic nature, or was it more of a technical nature, such as, "You forgot to put in a holster here.”

SEVERIN: Oh, it was...no. It was more of an aesthetic thing.

GROTH: I see. Can you give me an example?

SEVERIN: Nope.

GROTH: That's what I thought.

SEVERIN: Gary, I remember some funny stories about Kanigher, but I don't remember details.

GROTH: Can you contrast Harvey as an editor with Kanigher as an editor? What their differences were?

SEVERIN: Oh, I'm not any good at that sort of thing. All I can say is leave it, at this stage. They were entirely different. They worked entirely differently.

GROTH: What were Kanigher's preoccupations as an editor? Do you remember?

SEVERIN: No. I can only say that he was happiest when you turned in a well-drawn or well-inked job. When it looked like you had taken as much interest in drawing it and inking it as he had taken in writing it. Because most of the stories that I got from him were things he had written himself.

GROTH: Did you like his writing?

SEVERIN: Yeah, it was better than most of the stuff that I got from Prize. He was a good writer. A good down-to-earth writer.

GROTH: You did a cover for Frontline Combat #10. If was the Hiroshima...?

SEVERIN: The kid in the...

GROTH: Yes.

SEVERIN: I just ran across that the other day. It was a cover proof.

GROTH: Well, good. Now that you've familiarized yourself with it, Harvey said something that I thought was sort of odd. I wanted to know what your take on it was. He said, "I have a real strong feeling about kids and how I like them to be depicted. Wally did a good job here, because he's got a cute kid instinct, so your heart goes out. But on John's cover, the kid, he was real but not very appealing — "

SEVERIN: See?

GROTH: “I mean, he was appealing, but he should have been like that (points to a splash of Wally Wood's story). It struck me with this cover especially, that John didn't understand cute. I remember having great conflict about this cover."

SEVERIN: I know he did have problems with it. What he said was true. In the first place, it looks more like a real kid than a cute kid would look. And I don't see that I get anymore heartbroken over some cutesy-pie little kid being in a bombed out area than a normal, real kid, maybe an ugly kid. What the hell do I care? A kid's a kid! Perhaps at that time I couldn't draw a cute kid in the first place. But even today, I don't think I draw that many cute kids unless it's a real cartoony thing.

GROTH: Do you remember feeling strongly that it ought not to be a cute kid?

SEVERIN: No, I had a picture to draw, and I tried to make it look like as real as I could. A real kid in a mess. I remember Harvey drew a story—I think it was in that book. In fact, the cover might have had something to do with the story. I'm not sure if I'm remembering this correctly. He told Willie and me that when he finished writing it he cried. In front of him I didn't say anything, but later I was amused at the thought that he could get that excited over a story. Now, it wasn't something, you understand, that he was reading and it was all coming to him new because the writer progressed and then we hit this part and it affected him. This was something that he was thinking out in advance. It was calculated. How could you get moved to that extreme that you cry over something that you're—well, it just didn't strike me as a way to do it. I couldn't do that. On the other hand, if I had walked up to the picture, mine or anyone else's same thing, maybe it would have affected me.

GROTH: He was talking about the Hiroshima story?

SEVERIN: Yeah, I think so.

GROTH: Why did you draw the cover? Wouldn't it have made more sense for the person who drew the story to draw the cover?

SEVERIN: Yeah. I have no idea.

GROTH: Probably just scheduling.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Just a simple matter of not enough time.

GROTH: That one comment by Kurtzman struck me as odd, because it seemed to me that that cover would not have been enhanced with a cute drawing of a kid. In fact, it—

SEVERIN: That's what I mean. I couldn't have done a cute little lad and had it mean any more to me than if I drew an ugly kid.

GROTH: You drew a kid who was in agony, but it seems to me that it would have diminished it if the kid were too cute, because the whole point—

SEVERIN: Yeah. You're right. But I don't think he meant too cute. I think he was looking for a little more cutesyness in it.

GROTH: Sympathy toward the kid, yeah.

SEVERIN: I don't know how to draw cutesy stuff, so he gave it to the wrong fellow to draw.

GROTH: Or the right fellow, depending on—

SEVERIN:—which way you want to go.

GROTH: One of the things that Kurtzman often appreciated so much about your work is that you were able to capture different ethnicities....

SEVERIN: I could show you different kinds of people, too.

GROTH: Yes. [Laughter.] And you also captured the different looks of people in different historical times with their facial expressions, but also with their postures, gestures, and so on and so forth. Was this something that you studied?

SEVERIN: Yes.

GROTH: Did you study old photographs, or...?

SEVERIN: Yeah. Well, I didn't study them for that purpose. I indoctrinated myself accidentally. I was interested in all these subjects: costuming, and customs, and culture, and so forth. Being interested in those things, you run across the ethnicity of people, the attitude that they might have standing or sitting. Or under certain conditions, how they would react. Sometimes you're guessing, but your guess might come closer because you have been studying it. The ethnicity is easy. I once showed Harvey a drawing of an Irishman, side view. Then I had very much of a turned-up nose, the typical anthropoid nose that the English cartoonists used to do in the last century. And then I did a Jewish face, side-view—the exact drawing except that the nose went out into a hook nose. And the Irishman had his derby on tipped over on his forehead, and the Jewish fellow had the derby on the back of his head. And I said, "See how easy it is to identify people?" And then I took a normal face, just a face. This was about a week later. I did this one in pencils. I did a normal face, and I would put a Scotsman's bonnet on it and sideburns, and you had a Scotsman. I took the exact same face, and I did different costumes on the same face—moustaches of a British officer who was on and turned up at a real sprightly angle —and you immediately saw what these people were. And this was simply because of the custom that they had of doing certain things in certain ways. They cut their hair a certain way, or they wore their hats a certain way, cut their moustache one way or another. I could show you ten different guys with the exact same face and just do different things to them, which is what actors do on the stage.

GROTH: Do you remember a story you did called "Bird Dogs”?

SEVERIN: "Bird Dogs"?

GROTH: Yes.

SEVERIN: The name sounds familiar.

GROTH: Elder inked it; it's a story about a bomber, and many of the panels of the story are composed of an aerial view of the ground to be bombed. A lot of it is just the bombs falling and you're seeing these tiny explosions on the ground.

SEVERIN: No. I don't remember this at all.

GROTH: The reason mention it is because I thought the idea of interpolating the shots of the ground where the bombs were hitting from the airplane's point of view with the interior shots of the plane crew was inspired. You get a clear sense of how abstracted the deaths on the ground are from the point of view of the crew, and it makes an interesting visual pattern on the page.

SEVERIN: Yes, it's a wonder that he didn't take me up in airplane to show me. Oh, yeah. I did a job about a tank—I don't remember what that was, either—and we went out to Long Island to a National Guard Tank Battalion and we had to ride around the tank and examine it. All that just because I was going to draw the dumb thing. It's amazing. Oh, and very funny. I met an old crew buddy out there who was a Master Sergeant in charge of the place. [Laughs.] My God! So I got something out of it. But we drove around the tank. And of course, I had been in the half track in the service, so being confined in the armor didn't bother me. But a tank is so much bigger than what I was in, and—oh, boy!—you close down those hatches—I don't think I would have liked that. However, he went to all ends—to get his information. I think Jerry DeFuccio went down in a submarine with him?

GROTH: Yeah, that sounds familiar—

SEVERIN: Yeah, well, that's one thing I absolutely—side issue. OK? A very good friend of mine was the guy who fired the last torpedo into that great big Japanese battleship at the end of the war. They took turns. The Captain had a lottery (can you believe it?) and he won the lottery. He looked through the periscope and he said, "Fire one. Ba-da-boom!" How do you like that? What a thrill! In one way it's a thrill and in another way it's not. At that time it was a thrill. Now when you think back, you go—but enough talk about this stuff. Let's go on with what you wanted to do.

GROTH: One thing l wanted to ask you is, why did you start inking your work in the first place? You started inking your work with the eighth story you did.

SEVERIN: [Laughs.] You've got them numbered?

GROTH: I do.

SEVERIN: I just had to break loose and do something completely on my own. Because—I mean, I'm in comics, everybody's penciling, inking, penciling and/or inking, and etc., and I just wanted to do my own work. The whole thing, regardless of who was working on it with me. I just had to do my own. It never was like a complete job unless I did it. And God forbid anyone should put the hammer in the wrong place on the flintlock or something like that! No, I just had to do my own work. Like most guys, you know, you feel better when you've done it. I wouldn't have done it at all if I was so bad that they wouldn't hire my work. I wouldn't defeat my own purpose of working in the business.

GROTH: I noticed that when Elder inked your work, the use of chiaroscuro took on a very Milton Caniff-like look. Did you notice that?

SEVERIN: I think that in those days an awful lot of guys who were heavy in the black area, looked up to Milton Caniff and his work. I don't think that Willie ever imitated Caniff, although (son of a gun) I'll bet he could. But I don't think he ever did, consciously. I think that it's just that his use of blacks may coincide with Caniff's use of blacks. And that's because everybody studied Caniff. He's so good.

GROTH: Do you admire Caniff?

SEVERIN: Storyline, picture-wise, you know, the storytelling, I guess I thought a lot of him. I wrote to him in the service. Funny, I wrote him a—we were getting Male Call, the cartoon strip that he wrote for the army newspapers. I wrote him and told him how much we all enjoyed it. I said, "One small suggestion. I certainly hope that after the war is over you put together all these strips and put them out in a little book. That'd be great. Well, he wrote me back and told me that they had been thinking about that. About two years later I get out of the service and here comes Male Call in a little hardcover book.

GROTH: Wow. [Amused laughter.]

SEVERIN: Can't claim anything. I just tell you the story. I have the letter in the book itself but aside from that—which is kind of nice to know that the guy appreciated it.

GROTH: Yes. Right. Right.

SEVERIN: Enough said. Let's go.

GROTH: When I asked you if you really admired Caniff's work, you sort of hesitated.

SEVERIN: Yeah, because he's not my kind of an artist. My kind of an artist would be Hal Foster. OK? So if, in your mind's eye, you put the two of them side to side, you can see why I hesitated.

GROTH: Yes. Yes.

SEVERIN: I can't say that I didn't admire Caniff, yet if I say that, what do I say about Foster? Do I say I idolized him? So you know you can't go that far.

GROTH: The first strip you used Craftint in was a strip called “Buzz Bomb," which was inked by Elder, actually. The second strip you used Craftint on was "The Trap," which you inked yourself. I was wondering if you had something to do with Elder's using Craftint, or if you might have inked that splash page yourself?

SEVERIN: Oh, boy. I don't know. I can only put it to you this way—I don't remember Elder ever being interested in Craftint. So if this Craftint, in some strange way I put it in, I would say that I put it in. What was the name of it?

GROTH: The first strip you used Craftint in was called "Buzz Bomb."

SEVERIN: Naturally I don't remember that, either. No, but I would imagine if there was any Craftint being used it was me. Harvey was the one who started me on that stuff, too. I had always admired—there's the word, there you go!—I had always admired Roy Crane, and it never occurred to me that I had anything similar to his work in mine. Harvey pointed out the fact that I did. Why didn't I use this Craftint sometimes as he did? And blah, blah, blah—all that kind of stuff. So we put down our beers and I went and bought some Craftint. I started using it and I really enjoyed it. I am not at all like Roy Crane, but I sure wish I was. So I kept off and on sticking it in on things like explosions and so forth. Eventually, of course, I was put into a position where I could use Craftint on the whole doggone job. You know, working for Cracked Magazine.

GROTH: I don't know if you can confirm this, hit between 1951 and '54, it appears to me as if you did one strip each for Frontline Combat and Two-Fisted Tales, but you also did work for Prize Comics Western at the same time.

SEVERIN: Yeah.

GROTH: And during that period you may have been doing work for other publishers as well.

SEVERIN: Willie and I worked for Standard. We did a number of jobs for them. Mike Peppe was the art editor and Joe Archibald was editor-in-chief. It was one of these organizations that did a number of things and on the side they decided to throw in a couple of comics.

GROTH: So you were working for a quite a few publishers simultaneously.

SEVERIN: Anybody who'd pay me, yeah. No, as long as I had the time I would fill it in.

GROTH: Is the reason you didn't do more work for EC simply because they gave you as much work as they had for you and then you had to find other work?

SEVERIN: Right. Once in a blue moon, Al Feldstein had one or two or possibly even three jobs for him over a long period of time, but they always arranged—all the artists who worked for EC knew not only what book they would be in as a rule, but they knew how many jobs they were going to be getting.

GROTH: I see. You did several science fiction stones—

SEVERIN: Yes, those are the ones I'm talking about.

GROTH: Which would have been for Al Feldstein.

SEVERIN: Right.

GROTH: Somehow it doesn't seem as though you were terribly suited for science fiction.

SEVERIN: No.

GROTH: How did you feel about that?

SEVERIN: [Deadpan.] I'm not terribly suited for science fiction. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Can you tell me how you got roped into doing those?

SEVERIN: Well, I didn't get roped into it. It was an entirely different way of working, of course. It was more typical comic. They would tell the artist what it was they wanted and give him the script and off he went to his drawing board. Criticism would come afterward if there were any changes or anything like that. So it was back to — I won't say normalcy —the usual, is what I should say.

GROTH: How different was it working with Feldstein than it was working for Kurtzman?

SEVERIN: You didn't work with Feldstein. Let me make this personal. I'm saying this, not in general. I didn't work with Feldstein. I worked with Kurtzman. There was quite a difference. Feldstein was the editor. He gave me the script and looked over the job when it was completed and gave it his OK. His input was his wonderful ability in telling a story. I say I worked with Kurtzman, because whoever was working with Kurtzman worked with him. He talked over this and talked over that, and he took you on tank rides to teach you how to draw a tank.

GROTH: Feldstein never took you on a spaceship ride?

SEVERIN: [Joking.] Thank God! I'd faint. Yes, you got the idea.

GROTH: Did Feldstein give you layouts the way Kurtzman did?

SEVERIN: No. No. That's why I say that this was back to regular old comics. Al, he wouldn't hire you if he didn't think you could do the job. So once you were hired, he'd give you the script and he expected you to be able to do it. If anything was standing out and wrong afterward, you were expected to make a correction. That's all there was to it. He's very pragmatic and he was a great writer. God, I don't know how he turned out all those stories. Those were very, very fine stories.

GROTH: But he didn't fuss over the work like Kurtzman did?

SEVERIN: Well, no. [Pause.] He didn't.

GROTH: And I don't mean that in a derogatory sense toward Kurtzman—

SEVERIN: No. I was thinking about Kurtzman, to make sure you didn't misunderstand me when I said no.

GROTH: No. No. Those science fiction stories were very text heavy. Did that present a problem?

SEVERIN: Not—no. Sometimes—

GROTH: Huge balloons and captions filled with copy.

SEVERIN: Sometimes stories, when they're heavy like that, foul you up because you just plain outright don't have the room to put in what you want to put in or even to put in what they want. But no, Al's wasn't—I think part of the thing is that Al was an artist himself, and up to a certain point he knew he had to stop. Whereas most writers have no idea what can be put in and illustrated to carry the thought. Your continuity is shot so much. No, Al didn't—Al didn't fuss over the stuff. He wanted it to be right and if you came in pretty close to the mark that was good.