SIMON AND KIRBY

GROTH: I understand that what you did was that you and Will Elder drew some sample comic pages and made the rounds in 1947?

SEVERIN: Yes.

GROTH: Can you tell me what prompted you to do that in the first place?

SEVERIN: Well, I was watching Harvey, and he got me real interested in his strip called Hey, Look! that he did for Stan Lee. I was fascinated. He had a great sense of humor. The guy was so—what is the word? Fey. F-E-Y. Fey.

GROTH: Fey.

SEVERIN: Double F. I thought his humor was great. And that's as far as it went until one day I was sitting there looking at him drawing that stuff, and I said, "Harvey, I don't want to get personal, but how much do you get paid for that?" And he sort of—you know, you don't tell a guy right out, but he sort of gave me a rough idea. And I said, "How many of those things can you do in a day?" I started figuring out. I'm not good at math, but I figured that this was pretty good money. So I said, "Are there any openings out there?" And he said, "Yeah. You just go out there and see if you can get 'em. Turn out some sample pages and so forth." So that started it. Well, as a matter of fact Will Elder thought this was not a bad idea either, and Harvey said that my inking with a pen was not what was being done these days, and Willie could do this thick and thin nonsense with a brush. So he says, "Why don't the two of you get together?" So that's just what happened. We did samples. He would take some and I would take the others and we'd go to different places. At that time there were three hundred thousand little comic outlets, each one of them putting out a comic book a month or something like that.

GROTH: When you made the rounds, did you just pick up a bunch of comic books and look for addresses in the books?

SEVERIN: Gee, I never thought of that. I wonder how I did find out where to go. Most of the guys knew the addresses of these different places.

GROTH: These were all—

SEVERIN: I guess that would be it. You'd look up the address in the book. I never thought of that.

GROTH: And these were all in Manhattan, right?

SEVERIN: Yeah.

GROTH: I understand the first comic story you did was for Simon and Kirby.

SEVERIN: Oh, yeah. Right. Right. It was a crime story about a couple of kids out on a farm with aged adopted parents or—It was a murder. The boy was an S.O.B. kid. But of course, his stepfather was worse, and that gave him the excuse. I didn't much care for it.

GROTH: Tell me how you got that. Did you talk to Simon or Kirby?

SEVERIN: Well, both of them. Simon was more business and Kirby was more the friendly type of guy. The guy you put in the ads. You know, he does the talking to you and the other one does the talking about you. So Simon looked over my samples, gave me a critique, and so forth. And Jack gave me a critique. They were entirely different kinds of critiques, and it was wonderful. And they decided, "What the hell. Give him a break." So that started it.

GROTH: Can you describe, if you remember, what the Simon and Kirby Studio was like?

SEVERIN: See, it was incorporated in the business offices of Crestwood. I think the place was actually Pioneer Publishing, but one of the corporations was Crestwood. And I don't know which Simon and Kirby were actually working for. I could look it up in the books at the time.

GROTH: I think it was Crestwood.

SEVERIN: I think they had one of the offices, which was their studio.

GROTH: And they gave you the assignment. Did they give you a script?

SEVERIN: Yeah, right. Oh, it was a good thing they did at the time. I wouldn't have known what to do. They gave me a script, a typical script. They wanted to see a couple of pages. I brought it in and then they brought in Willie's (Bill Elder—we used to call him Willie)—gosh, I lost track of what I was talking about. That comes with old age. What the hell. They brought in his inking and we both passed muster and we continued—

GROTH: I assume you have no idea who wrote that script?

SEVERIN: Oh, Lord no. It wasn't Simon or Kirby. It wasn't their type of writing at all.

GROTH: In as far as this was the first comic you drew, am I correct in assuming you didn’t quite know what you were doing and you just felt your way along?

SEVERIN: Yeah. I had no—well, one thing that was natural with me was that I had a natural ability for continuity. But I also had a natural inclination to make everything like it was being done on a stage. And Jack and Simon, they both explained that [I needed to] vary the shots. You know, up, down, across, behind things, and so forth. Well, that was exciting. It had never occurred to me to do that because this isn't the way that I see things. It was great! But no, I didn't know [much about drawing comics]. I more or less caught on later on. But I still enjoy just shooting straight on. [Laughs.] Here come the Confederates, straight ahead on you.

GROTH: You used the old proscenium arch perspective.

SEVERIN: But the other stuff actually adds a lot to the composition of the page and the interest of the reader.

GROTH: Well, you became quite masterful with that within just a few years.

SEVERIN: Yes, but I had to learn it. I didn't know it. There was nothing natural about that.

GROTH: Did it come easy to you?

SEVERIN: Yes, when I had to do it. It's just that it had never occurred to me to do it.

Wait a second. [Pauses to think and count.] We got our first script at the end of '47. I didn't complete it until '48, if that's what you're talking about. That's when we got the first job.

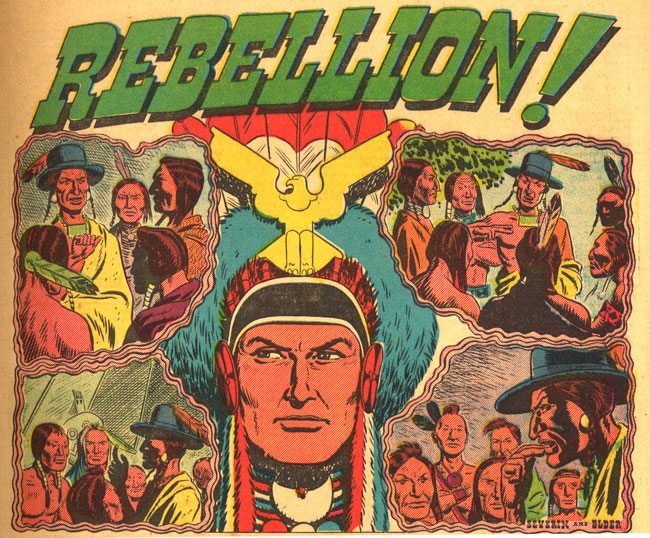

PRIZE WESTERN COMICS & AMERICAN EAGLE

GROTH: Between '47 and '51 you worked for Headline–

SEVERIN: Well, that's another portion of Crestwood.

GROTH: —Prize Western—

SEVERIN: Yeah, that's the sub-name of the book. It was called Prize Comics Western. Western was the big word.

GROTH: You didn't do much work for Simon and Kirby.

SEVERIN: How I stopped working for Simon and Kirby was they had an editor by the name of Nevin Fidler. He was doing the Western thing. He had come up with a character. Or they. Somebody. You know, the vague persons. They. He probably talked it over with them, whoever they are, and they decided this American Eagle would be a good character. So he asked me if I knew anything about Indians and would I like to draw it, and I said, "Swell. Let's go." And so I started doing Prize Western's "American Eagle." But prior to that, I had been working—I imagine I was working. I don't remember—but I imagine I was working for him when I did their other character, a very well known personality called the Black Bull—who had an English butler ride alongside of him instead of Tonto, and his war whoop was "Moooooo!" M-O-O-O-O-O-O. And out of the clear blue, when the girl was in distress, she heard in the woods, "Moooooo!" And then she knew, "Here he comes! He'll save me!" [Groth laughs.] My God in heaven, "Mooooooo!" Can you beat this?

GROTH: It's pretty inspired.

SEVERIN: [Sighs.] They were doing the Lazo Kid, and I started to do that with a certain amount of regularity. And then came the American Eagle, the third one down the line.

GROTH: You also did something called Fargo Kid.

SEVERIN: Was that for them?

GROTH: I believe it was for Prize.

SEVERIN: Fargo. I don't remember. I remember the name Fargo Kid, but I really and truly don't know who I did it for. There were so many "Kid"s that I did covers for or stories for.

GROTH: Now, you also did a couple of things called Western Love and Young Love.

SEVERIN: Ha, ha, ha. I did? Oh boy. I betcha’ those are gems.

GROTH: Well, I haven't actually tracked those down, but—

SEVERIN: Don't bother. Please.

GROTH: Would those have been romance stories?

SEVERIN: [Chuckles.] Yes, as embarrassing as they could possibly be. At that time, I knew what girls were but I couldn't draw them well. And they had girls hugging guys and kissing—oh, God! I just purely couldn't draw that. I'd have to get all the comic romance books around. You know, see how other guys did them. Then I would imitate what they did until I caught on. Thank God I never got stuck with the romance stuff. Oh, man. That was terrible.

GROTH: Why do you think you had a problem drawing that?

SEVERIN: I couldn't draw girls. My girls looked real, the kind of girls you'd see on the street. Not the street corner, mind you, on the street. And these guys were capable of drawing idealistic blondes and—it took me so long to learn how to draw a cutesy-pie little gal. I would draw girls and they'd have hooked noses or too big a mouth, because that's the way they are. They're just like guys. They look individual—they're very different from one another. I had no interest in drawing pretty girls. I'd rather draw a horse.

GROTH: Hmmm. Well, that's interesting.

SEVERIN: A pretty horse, of course.

GROTH: Right, of course. Well, you certainly, eventually learned how to draw pretty women.

SEVERIN: Well, it was hard to do, I'll tell you. As a kid all I'd draw would be soldiers and cavalry charges and knights in armor. No girls in these stories.

GROTH: I assume at this point you would pretty much take anything they gave you to do?

SEVERIN: Oh, well. Most guys did at that time. You were looking for money. You had to do as much as you could.

GROTH: Can you describe the editorial process? You would literally go to the office and they would hand you a script?

SEVERIN: Yes.

GROTH: And did you do all this work with Will Elder?

SEVERIN: At the beginning, yeah. What happened usually is that they would hand you the script, and they would like to see the pencils first. And that was all right with me since Willie was going to be doing the inking, But when it came time for me to do my own inking, I just couldn't do that. I mean, my pencils were so tight that you could go ahead and print from them. So when I finished a drawing, I didn't want to have to go back over the drawing and redraw the thing with ink. I had a real problem getting across that idea to them, but whoever it was that let me start in—I think it was Stan Lee—why, it worked out pretty well and everyone was happy. Or at least they weren't unhappy. From then on, they'd give me a script, and I'd just bring the whole shooting match in. That was great. I didn't mind if there was—even the few times that there would be a whole panel, let's say, to change. It didn't bother me. I'd just take it out. Take out a new board and put in the new drawing. I didn't mind that. I'd rather do that than bring in pencils.

GROTH: So you're saying that when you inked your own work, your pencils were much looser?

SEVERIN: They were so loose you couldn't hardly ink on them.

GROTH: Is that right?

SEVERIN: You'd have to have one hell of an imagination to know what the devil the guy was drawing. "What the hell is Severin thinking?"

GROTH: And you did that because basically you saw it as drawing twice if you inked it.

SEVERIN: Yeah, right. I knew what I had drawn, and the looseness that comes out, if there is any looseness in my work (which there isn't too much any more) but if there is, it's only because my pencils were loose. So I kept them pretty loose, but a poor inker could never do much with that. But when I did give an inker the stuff, I would make 'em so tight that he couldn't miss anything.

GROTH: So when you inked you own work, you were, in effect, drawing with the ink to some extent.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Mostly, yeah.

GROTH: But when someone like Will Elder inked your work, the pencils were very tight.

SEVERIN: Yes. And the appearance of the work actually came out more like the inker than like me, I imagine. He was able to put anything he wanted into it, because the blue print was there. He had no problem. He could alter anything he wanted and know where it would go, because, as I say, everything was there. I'm repeating myself. That comes with old age, too.

GROTH: When you brought in pencils to show the editors, it sounds like they scrutinized them pretty carefully.

SEVERIN: They did. They did. There would be alterations.

GROTH: What kinds of editorial suggestions or changes did they request?

SEVERIN: "Severin, you forgot to put in the dog over here." Or, "I don't like this character. He should be more mean looking." Things like that. I don't remember anybody complaining about too many corrections. Oh, Harvey would make big corrections, but that was a different animal. The work that we were doing for Harvey was an entirely different thing. Much better comic work, but not everyone could work the way Harvey did.

GROTH: Can you tell me how it was different? How do you mean that?

SEVERIN: Well, first of all, all of the artists got complete, absolute complete layouts. Harvey was like a movie director. He knew exactly what he wanted, and he would write the story with the artist in mind, knowing what the artist would [do]. Which is not done. So when the artist would bring the stuff in after following the layouts and everything, there was a reason where Harvey could say, "I wanted the camera angle a little more this way or that way," because he'd envisioned the whole thing. And we agreed, when we took jobs from him, we knew damn well that's the way it was. And it was great! Some of the best work the guys did in their careers were done for Harvey under those, what do you call it? Restrictions. They're not restrictions. Directions, I guess. Sometimes it's very difficult to work with a man like that, because the guy was fantastic! Unfortunately, along with his great ability, he had to take more time than the average person. You can see how that would be. My God! He'd have a whole book. It was different when he was doing his own work. He just had that one job, and he would work it out and work it out and work it out, and it would come out great. But when he was writing a whole book for four other people, he would take as much time with each one of those people. Working for him was delightful, it was terrible, it was just—he brought out the best in all of us, and sometimes you'd like to break his damn neck. But by God, he was good.

GROTH: When you worked for Prize, was that a pretty straightforward situation where they would give you a script? Or I think you started writing your own scripts at a certain point?

SEVERIN: Yeah, well that, and the fact that I wrote with Dawkins. The two of us, he did the actual writing on 99% of the stuff but I would work the ideas out with him, break down panels with him, and so forth. And then when it came to actually putting the balloons in, etc....he actually did the writing on that part of it. It was fun! At that point, for whatever reason (mostly good for me, anyhow) Prize just took the jobs. I would suggest let's do a single page of Indian artifacts, Western lore, and so on and so forth, and they'd say "Sure." So I'd go home and draw up a bunch of stuff, decorate it with Indian designs or whatever, bring it back and they'd take it and print it. I felt like it was my Grandmother taking and giving me the jobs. She never complained! It was wonderful!

But they were a good bunch of easy-going buds. Joe Giella, he was the editor. Whatever he said, it seemed to work. So what the hell!

GROTH: If I remember correctly, you said that you were given scripts for American Eagle at first and you didn't think much of them. And eventually you and Colin Dawkins started writing them.

SEVERIN: Yeah. Right. The reason—this is so you will understand what I mean. When I told you about the Black Bull and the Lasso Kid, the same guy who wrote them was writing American Eagle. I wanted the American Eagle to be something more, to be more—if you're going to do Indian let's do Indian. You know, he isn't just another Superman in a loincloth or some damn thing. Well, he was hardly a Superman, but you know what I mean. So, wanting it to be better and throw in as much as Dawkins and I knew of the West and Western lore, I felt that we could do a much better job for the book. So not knowing where my—[chuckles] how much trouble I could get into, I proposed this to Mr. Reese who was the publisher there, and he said, "You really feel that way?" And I said, "Yep," like a real big shot. (I didn't know what the hell I was doing.) And he said, "OK." So we started in doing it and they worked out. We didn't ever get any complaints about it. It either worked out or he thought I was crazy and didn't dare argue with me. [Laughs.]

GROTH: But you actually had the professional certainty to go up to him and say, "I think I can do a better job than the current writer"?

SEVERIN: Yes. I did do that, but I don't know how professional I was. You threw that in. [Laugher.] That's pretty nice.

GROTH: There's a strip in Prize Western that you inked penciled by someone named Gevanter.

SEVERIN: I inked his stuff?

GROTH: Yes, you did.

SEVERIN: Are you sure it wasn't he that inked over mine? The reason I say that is...

GROTH: I can't be sure.

SEVERIN: Well, you should be. I mean, you should be because you study these things more than I. You, I'm sure, would recognize my inking. Here's what the deal is with Joe Gevanter. He was a fool of a guy who—geez, don't write that in there! Anyhow, he was a nice old guy, and... As a matter of fact, he gave me a Japanese Nambu one time. Anyhow, we didn't have time, because we didn't have time, Bill and I, to do all of the American Eagle stuff. So the short story in the back of the book we gave to Joe Gevanter. And it worked out fine. All I told him is just imitate Bill Elder and myself as much as you can and it'll work out fine. And it did. So I just can't picture me inking on his stuff. But, if it looks like my inking, that's what happened.

GROTH: Well, the only reason I inferred that is that your name came after his in the signature.

SEVERIN: Oh.

GROTH: But now that you asked me, I'm not sure it looks like your inking.

SEVERIN: That makes....Well, if it was done with a brush, it wasn't me.

GROTH: Yeah, it looks like it was done with a brush. So he would have inked you?

SEVERIN: Yeah. So I guess he had inked my stuff.

GROTH: And how did you know him?

SEVERIN: I don't know. He was looking for work. There were so many of these guys in comics in those days who floundered around who would draw and who would ink. He was such a nice little guy, and he was just freshly married, so I figured, "What the hell? Maybe he could do something with this." That's all. As a matter of fact, when I quit American Eagle, I gave the whole shooting match over to him. I don't know how long afterwards he kept it up, but well, it was kind of up to him at that point.

GROTH: You drew a strip in Prize Western called "Two Gun Showdown." A good part of it is silent, which was also somewhat out of the ordinary for the period. Would Colin Dawkins have written a script like this?

SEVERIN: Possibly. If I saw it I would know for sure. What did it entail?

GROTH: It stars a gunfighter named Buck Dolan...

SEVERIN: That's Dawkins. I'm pretty sure he wrote it. It might have been he and I working on the thing, but he would have to take the credit for the writing. The minute you said Buck Dolan it did some kind of a thing in my head. I don't remember it exactly, but I'm sure it was him.

GROTH: One interesting detail that I noticed was that Buck Dolan's pistol was drawn backwards in its holster. Was that historically accurate?

SEVERIN: It came from the fact that an awful lot of Westerners rode horseback and your pistol had a bad habit, in rough riding, of sliding out [of the holster] if you were sitting and the butt is to the rear. Especially those long pistols, so a lot of holsters even had flaps put on them. But when they went into the Army—and so many guys were in the Army during the Civil War—the cavalry wore their pistols in that fashion for that reason. When they came out to the service, they had gotten in the habit of having the butt forward, like Hickok wore the two guns he... Well, half the time he didn't have a holster. He just stuck 'em in his belt or sash, whichever he was wearing. But that's the only reason why they did it that way, to keep it from getting lost when you're on board a horse.

GROTH: Well, I figured it was probably accurate.

SEVERIN: Oh, it was. You can double check in all the Civil War pictures. You'll see 99% of the guys'll have holsters the butt'll be forward.

GROTH: How did you feel you were treated professionally in comics in the '50s when you were—well, you would have been in your late 20s, early 30s.

SEVERIN: Yeah. It never occurred to me as anything. I was an employee and I think I was treated fine. If I didn't like it, I could quit. If they didn't like me they wouldn't hire me so I didn't have a problem with people I—all the editors I ever worked for—Stan Lee, Sol Brodsky, Jim Warren, or whoever—I never had any problems with them.

GROTH: Of course, you didn't own your own work. You were paid for your work, and that's the first and last you ever saw of any return on it.

SEVERIN: Right. You're not kidding.

GROTH: And it didn't occur to you that you would have been better off if you had owned the work you did?

SEVERIN: I don't even think they would have paid attention to the vast amount of the artists that they had claimed that they wanted to own their own work. I don't think that would have happened. There may be some guy who I'm missing here that might have enough clout to be able to do that, but on the whole I don't think that anybody stood a chance.

GROTH: Well, that only happened occasionally. Kirby owned some of his own work—

SEVERIN: That was later on, wasn't it?

GROTH: I thought when he was at Crestwood that he and Joe Simon owned a lot of the work they did.

SEVERIN: Maybe they did. See, I didn't know. I—

GROTH: And Joe Kubert somehow managed to own some of the work he did.

SEVERIN: Oh, I guess Joe did, yes. You see, at that time I had only a speaking acquaintance with DC. It wasn't until Marvel dumped us on the marketplace that I went over to DC to work. I just wanted over, they sent me over to Kanigher and I got started working with him.