From The Comics Journal #173 (December 1994)

You’ll forgive Jeff Smith if he doesn’t always believe the hype. While many call the creator of the enormously popular self-published Bone “an overnight success story,” Smith not only remembers the lean months trying to get that project over the financial hump, but the 10 years of preparation, trial runs, and nightmarish dealings with newspaper syndicates that preceded the awards and adulation. While some view Smith as a fully realized talent that seemingly appeared out of thin air, Smith recalls weeding out the jokes that didn’t work and the long nights spent honing his craft working on drawings for animation. While certain individuals refer to Bone as a “distributors’ darling,” Smith can point to the research he did and the conscious business decisions he made in bringing his comic to the attention of a select few within the industry.

Get this straight: a lot of what makes Jeff Smith’s Bone a success is that Jeff Smith worked his tail off making it one. Smith didn’t try to place himself in the “all ages” section of ’90s pop culture, or market himself in opposition to corporate-owned, gimmick-laden ultra-violent superhero titles, or push his comic as part of a new trend In comics self-publishing. He benefited from one or all of these things because he and his work were ready to be discovered. Other people worried about how best to position themselves; Smith got good, did his homework, and refined the project he always dreamed of seeing in print.

Given their public reputations, Gary Groth interviewing Jeff Smith brings to mind a man with a bloody club chasing a baby seal across a snowy waste. In actuality, Smith more than holds his own. In this interview, conducted in October 1994, Groth met a Jeff Smith who wasn’t afraid to examine his formative experiences, life’s work, and place in the medium.

All images ©Jeff Smith unless otherwise noted.

AN EXTREMELY EXCITING TIME

GARY GROTH: From what I know of you, Jeff, it seems to me that you were more interested in newspaper strips than comic books.

JEFF SMITH: That was the kind of comics I wanted to do. It started in the fourth grade when I got hooked on Pogo by Walt Kelly. From that moment on I began to try to figure out more about cartooning, more about newspaper strips, what tools were used … I can’t remember where I first got the idea to get nib pens, but I got some. It’s amazing: when you’re a kid, you don’t have the ability to just get into a car and go down to an art store and buy a nib pen — God knows where mine came from, I can’t remember. But I was immediately trying to figure out how to draw, how to ink, how to do the reproductions so I could do a newspaper strip — like Peanuts, Dick Tracy, Doonesbury — all that stuff, I just loved it.

GROTH: You started reading newspaper strips when you were a kid.

SMITH: Oh yeah.

GROTH: I assume you must have been reading comic books as well.

SMITH: I was.

GROTH: But they didn’t quite captivate you as thoroughly as newspaper strips?

SMITH: Yes and no. I don’t recall ever wanting to do that when I grew up. Although right around the time when Neal Adams and Dick Giordano were working together doing Batman and the Green Lantern stuff, there was a moment in there where I was just mesmerized by anything Neal Adams did I had to find it. It didn’t matter if I found it with the cover torn off, I had to have it.

GROTH: Adams is not an artist that one would instantly think you’d admire as much as you do. Because your own work is as far from his as you can get.

SMITH: Everybody says that. No one really believes that he’s my number one comic book influence. But he is. I think if you look at my trees, or proportions, or drop shadows on the people, or the shadows cast by trees or inanimate objects … I see it very clearly. And Neal could make his drawings act.

GROTH: I understand your parents would read you the Sunday comics.

SMITH: Yeah. My dad used to read Peanuts to me when I was a kid. One of the reasons I learned to read was because he got me hooked on Charlie Brown and Snoopy and Linus.

GROTH: How old were you?

SMITH: That’s a good question! First or second grade? I really don’t remember. But that was a big event, on Sunday, my dad reading the Sunday paper to me.

GROTH: Were your parents encouraging of your artistic interest?

SMITH: They definitely were. I remember my dad sitting down and showing me how to draw Woody Woodpecker. It was a real simplified version – like drawing a crescent moon. I was 3 or 4 at the time. He showed me how to draw an eye; how it had the white part and the little black part was the pupil and that aimed forward. Very rudimentary stuff, but it’s still with me.

GROTH: What did your father do?

SMITH: He makes ice cream products. My cousin and my dad’s brother came out to visit and they wanted to see my office where I make comic books, then go to my dad’s plant where he makes ice cream bars. I was thinking that to this little kid, my cousin, this has to be a great vacation! [Laughter.]

GROTH: So each generation is corrupting children! [Laughter.] Now, you also watched a lot of animated features like Bugs Bunny, Tom and Jerry, Mighty Mouse …

SMITH: Yeah. I loved that kind of stuff. I have very clear memories of going on family vacations in the summer in New England where they had more cartoons than they had where I grew up in Ohio. You could see things that were exotic to me, like Astro Boy and Hercules, and some scary thing where the face didn’t move but it had human lips superimposed on it. That was an extremely exciting time.

GROTH: The time period when you describe your love affair with Neal Adams, that would have been around ’71, ’72, ’73?

SMITH: I started before the Green Lantern stuff, around ’69.

GROTH: Underground comics were coming out around then. Were you paying any attention to them at the time?

SMITH: I was a little too young.

GROTH: How old are you?

SMITH: I’m 34, born in 1960. So in ’69,1 was 9 years old. Didn’t go into headshops or anything! [Laughs.]

GROTH: Right — you weren’t reading Mr. Snoid at the time.

SMITH: No, but I knew about it. I knew about Fritz the Cat because that had broken out of the underground; I could go into a bookstore and see a Fritz the Cat collection. I knew I wasn’t supposed to get anywhere near it, but I did anyway. I knew about Robert Crumb, and for some reason I think I knew about the Fabulous Furry Freak Bros., but beyond that I hadn’t actually gotten into Zap or anything.

HANDS-ON EDUCATION

GROTH: You went to Ohio State and that was, as far as I can tell, the first time you actually drew a strip that was published, in the student newspaper?

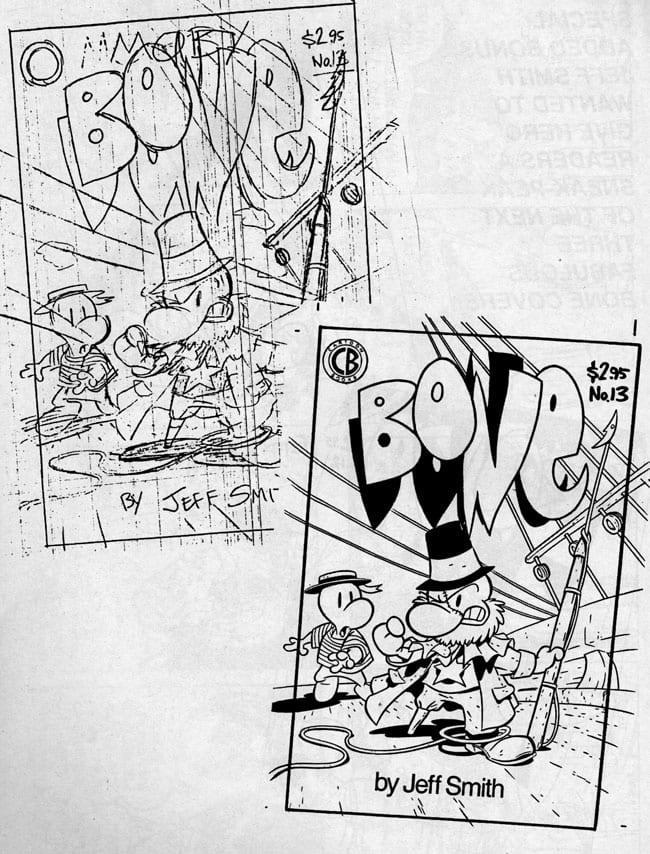

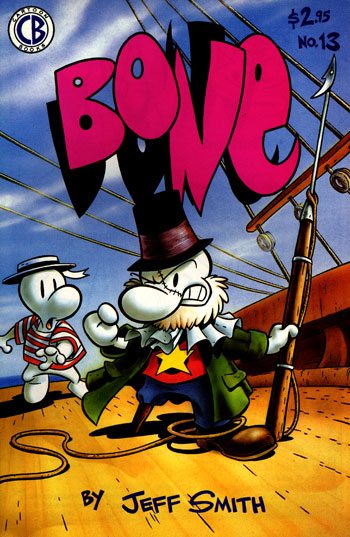

SMITH: The first strip published, yes. This is where I redeveloped the Bone characters I’d made up when I was a kid into a Heavy Metal type of universe — cartoon characters who are trapped in a fantasy world that’s full of humans.

GROTH: It’s clearly a fantasy environment.

SMITH: The story that ran in the OSU Lantern was a work in progress. It’s where I created the world as I went and concepts solidified. Some of the jokes worked and some of them were incredibly sophomoric.

GROTH: How much of the current Bone material is a reworking of that?

SMITH: In overall structure, it’s very close. It’s the same idea of the Bones getting run out of Boneville and all the same characters are there. But the difference is, I was just going straight forward. I wrote it as I went, and I did it every day for four years and I got to know the characters very well, I got to learn how to write a lot better, and also this over-arching story came into focus. So I had the benefit when I first started doing the comic books, of going back and reading all that. I got to get rid of all the jokes that were really lame. I didn’t have to do those for a wider audience. I tried those out, they bombed, they’re gone. But I used all the jokes I got good feedback on. Also, since I know the end of the story now — which I didn’t when I did it in college — I was able to begin right away at the beginning with a structure, and add little incidents, little clues; I could foreshadow the concept that there was an ending, that it is all one story.

GROTH: Did the four-year stint at the college newspaper encompass the entire storyline?

SMITH: No.

GROTH: So if someone reads the end of that, they’re not going to know the end of Bone.

SMITH: No. In theory, you probably could piece together all those papers and if you read them all you would know some things. But I never did get to the actual ending. The real ending, the big, big ending, doesn’t exist yet. Well, actually, I have written it down now and the last three issues of Bone are written, but they’ve never been drawn out; they’re in prose form.

GROTH: How was the strip received at college?

SMITH: Mediocre. There would be people who thought it was great and were really into it, and there were a lot of people who just didn’t get it: “It’s a comic strip, so how come it’s not funny?” [Laughs.] I did cliffhangers and I guess they weren’t always obvious. You’d get to the end of the four panels, and to me it’s a cliffhanger as long as a revelation was made.

GROTH: This was ’78 to ’82?

SMITH: No, I didn’t go to college right away. I got a scholarship to an art school, but only made it until Christmas there.

GROTH: What art school was this?

SMITH: The Columbus College of Art and Design, which is a good school, but not if you’re interested in cartooning; at least it wasn’t in the late-’70s,

GROTH: Is it fine arts-oriented?

SMITH: There were two curriculums you could choose from: fine arts or commercial art. I wasn’t very interested in fine art at the time and I thought commercial art might be more towards illustration, towards cartooning. I thought there would be some progression that would get me towards what I wanted to do — but I was wrong. Although in that brief amount of time I did learn things. I learned color theory and stuff. [Laughs.]

GROTH: Which you use very well.

SMITH: Yeah, which is a big part of my life now! [Laughs.]

GROTH: How long did you go there?

SMITH: One quarter.

GROTH: [Laughs.] That must be a record. So then you took some time off?

SMITH: Yeah, I had a few different jobs, mostly blue collar. I worked in a college bookstore for a long time, did a lot of paste-up work, and I did a stint at my dad’s ice cream factory. It was quite an experience to know what it was like to work on an assembly line.

GROTH: Did it turn you off to ice cream?

SMITH: For a while! [Laughter.] You were allowed to eat as much as you wanted. There was no limit. That kept you from stealing ice cream, I suppose. If you eat 12 ice cream sandwiches before lunch on your first day, you don’t want any more!

GROTH: So what year did you finally get to Ohio State?

SMITH: 1982. I said to myself, “OK, am I really going to work in factories for the rest of my life? No, I think I’ll go back to college.” So I enrolled at OSU, and one of the reasons I went was because sometime in there I got really hooked on Doonesbury. I had decided I wanted to take a shot at newspaper strips. I carried around these three giant treasury-size editions, almost like Bibles. I thought they were the next evolution after Walt Kelly, for me. That was the most popular strip on campus at the time too. So I picked OSU mostly because they had the Lantern, which was a daily newspaper. It had a circulation of 50,000. In my mind, that was exactly the tool I needed to practice my vocation. I had come to the realization that I wasn’t going o be able to go to school to get taught how to do this, so the only thing I could do was find somewhere I could practice. So I took one journalism class in order to be on the paper and I enrolled as a fine arts student, then submitted some Thorn strips to the Lantern and they accepted them, and off I went.

GROTH: So you actually enrolled with the explicit thought of having a strip in the paper.

SMITH: Yes, absolutely. In art school, they explained to me that cartooning was just a complete bastard child of the arts and wasn’t real. That was kind of shocking to an 18-year-old. “Oh my God! You mean I’m not allowed to be a cartoonist? Is that what you’re trying to say to me?” So immediately I began looking for ways to use this system that didn’t accept me in ways I could at least use it. I went to 3-D concept classes, then went home at night and would start my comic strip about 9 o’clock at night, finish by 2 at the latest, and I did that every day for four years.

GROTH: So you’re an incredibly disciplined individual.

SMITH: It sounds that way when you say it … [Laughs.]

GROTH: But in reality you’re lazy!

SMITH: Yeah!

GROTH: But no, that really does sound pretty damn disciplined. To keep that up for four years on a daily basis …

SMITH: It does sound that way. And it is. If you’re going to do it every day, you have to do it every day. But you still go out and party and have a life. You just have to make sure you’re home in time to work on your comics.

GROTH: Your major was fine arts there … Did you actually learn anything about fine art?

SMITH: No, not really. [Laughter.] I was going to try to be nice about it, but no.

GROTH: Did you learn anything at the university that could be applied to comics?

SMITH: Yes. Not much of it was in any of the curriculum. What I got out of school was that I met other people with similar interests, and that was great. At the university at that time, Lucy Caswell and Milton Caniff were setting up a library based on Caniff’s papers, The Library for Communication and Graphic Arts (now the Cartoon, Graphic and Photographic Arts Research Library). I began to go there early on, and that was an incredible experience for me right at that moment. To be able to put my hands on originals. At that time I was using a #2 pencil and a nib pen on a giant piece of cardboard, and all of a sudden I could see blue lines underneath and inks that were laid down by a brush and they’re doing it with two-ply Bristol instead of the piece of cardboard that I was using. I learned how to network. I learned how to move about in the journalism building, and if I wanted to make sure that the comic strip I had done was going to work right, I went over and got to be friendly with the guy who was running the PMT camera and got him to show me how to shoot it, shrink it down and paste it up. So I learned exactly how thin a line can be before it drops out when you shrink it down. I learned a lot of mechanical aspects of producing a comic strip. So that’s what I got out of it. Getting to know people and learning how to use resources. As far as academics, the only thing I really got out of it was art history, which I couldn’t believe ended up to be a huge turn-on. I was absolutely amazed — this will probably sound really obvious — but studying Western art history is like studying the history of the West … I just couldn’t believe it, I really was interested in it. You take this class and start talking about art in Egypt and Greece, and the societies that supported it (and were supported by it). I thought that was fantastic. But as far as learning how to paint — I learned how to stretch a canvas in high school. Not much new in college: “Here, let’s throw some sticks on the canvas, and if they stick, then we have a piece of art.” That was pretty much what art was back then.

GROTH: Did they teach you things like draftsmanship?

SMITH: No.

GROTH: Any fundamentals?

SMITH: No, in fact if my memory serves me, that was actually viewed as a weakness. Except for life drawing. That was good. I did learn stuff in that. I mean, when someone’s standing up in front of you naked, you pay attention. So almost by definition, you learn more.

GROTH: It sounds to me like the curriculum was really enslaved to abstraction.

SMITH: That was big at the time. Performance art was big: people sitting on stools yelling things with a slide show going on over them. Actually those are interesting to watch and I’m not putting them down as something … But I did want to learn some draftsmanship skills, and I thought there would be things I’d be taught that I didn’t get taught. I don’t know what they were. All I know is, academically, it was a bust for me.

Continued