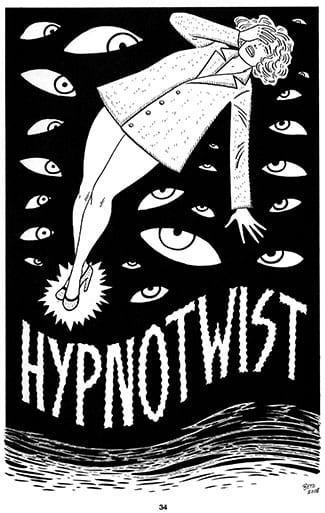

NADEL: And that brings us to “Hypnotwist”, a little bit, which is one of my favorite things you’ve done in a while.

NADEL: And that brings us to “Hypnotwist”, a little bit, which is one of my favorite things you’ve done in a while.

GILBERT: Oh you haven’t seen the added pages yet. When it’s reprinted it’ll have added sex scenes— I couldn’t fit all the pages in there. It’s going to be one of the special editions of the Fritz books that are reprints, but it still belongs in the series. The reprint books going to be sprinkled out through the series. So it won't be a new book technically, but it’ll have more pages. We’re getting into the bookstores with the new Love and Rockets, and I shied away from putting in too much sex at first, because I was concerned about browsers. Someone picks up that book and they’re seeing hooters and boners and stuff that might just turn them off. It was too soon for the series to have that, to get the reader kind of spooked.

HODLER: It’s hard to read these on the train.

GILBERT: Yeah, exactly. [Laughter.] So I wanted to back that off at first, so I left all the [nude?] stuff out for the most part in that story. But they’re not important scenes — they're just fun scenes that go into the story.

NADEL: Is the process different for something like “Hypnotwist”? Because it’s not dependent on plot, necessarily — it’s sequences, but they’re more graphically intense than a lot of other stuff.

GILBERT: When Cave In came out, the Brian Ralph story, I looked at that — this was years ago when that came out, I don’t even know when that was.

NADEL: It was a little over 10 years ago.

GILBERT: Yeah, and I looked at it thinking, “I can do a story like this. This guy’s getting fucking awards. I can do a story like this.” So I started coming up with a story like that, but I kept putting it aside. And then years later when I started putting together the Fritz books, I wanted to come up with titles I could work towards, like Troublemakers. Speak of the Devil. I just liked titles, and that one, I had “Hypnotwist,” was an idea I had just for a name. And I thought that it would apply to the story, that’s all. So I put the two together. So that’s my Brian Ralph story.

NADEL: That’s your Brian Ralph story? [Laughter.] That’s pretty funny. But it’s a little more than that, I mean —

NADEL: That’s your Brian Ralph story? [Laughter.] That’s pretty funny. But it’s a little more than that, I mean —

GILBERT: Oh no, yeah. Once I put myself into it, it becomes a whole different thing.

NADEL: Yeah, but it also goes back to some of the stuff you were doing in what became Fear of Comics. Fear of Comics collected New Love, right?

GILBERT: Yeah, New Love without the Venus stories.

NADEL: It’s almost like you’re doing like Charlton Ditko stories, but way different and also kind of connected to Rick Griffin, almost.

GILBERT: It’s all that. Also Ditko and Crumb’s early work.

NADEL: Like Head Comix.

GILBERT: Yeah, or even ZAPs, early ZAPs by Crumb. You read a two-page story, you read a one-page story, you read a long story; Crumb was riffing and just having a good time. That made a big impression on me, when I was reading it as a kid.

SANTORO: I mentioned that I thought that Speak of the Devil had a big ’70s-Ditko-Kirby vibe, like Demon, and you said, “I don’t really see that. I think it’s just kind of in me.” And I think there’s that no hesitation in your career right now, where everything’s just coming out. It’s not conscious.

GILBERT: It’s not conscious, but it probably is from there. I just don’t think about it anymore. I read those Ditko/Kirby comics so much since I was a kid, that that’s what comes out still.

NADEL: Do you still read them?

GILBERT: Sure, just because it’s Ditko/Kirby, and of course. Hell yeah. Oh, are you kidding me? Amazing Adult Fantasy, 7 to 14, I just … as a kid I couldn’t believe how cool they were. I just thought they were the coolest. I liked them so much. I just thought that was Ditko’s strength, and then superheroes came, and he was great at that, too. Dr. Strange. And then after that [Gilbert makes a sound like a rocket/bomb falling]. [Laughter.]

NADEL: But did you guys ever seek out your idols at all over the years?

GILBERT: No. It always backfires on us. I get too fanboy and say the wrong thing and they get pissed off.

JAIME: Yeah, I wouldn’t know what to say.

NADEL: What did you say?

GILBERT: No, it’s just that over-praise can creep people out. When Bob Bolling was at Comic-Con about 3 years ago —

NADEL: Bob Bolling is still alive?

GILBERT: I think so. Lives in Florida. Retired I believe. They got him and Dexter Taylor at the Con once. Taylor’s the other Little Archie artist. He’s the guy who Bob Bolling — You’d recognize him. He did “Little Pureheart the Powerful.” He did those Little Archies that … he basically took over Little Archie when Bob Bolling left.

NADEL: OK.

GILBERT: And both of those guys were there, and I just, well you know, I’m never going to talk to these guys ever again. I just over-praised Bob Bolling to the point where he was like, “This guy’s crazy.” [Laughter.] Jaime, remember, you went to pay him for the art, and you gave him extra money and he got mad. It was just weird.

JAIME: Yes, he had this sketch and I go, “Oh, cool.” And he goes, “5 dollars.” And I went, “Well, here, have a 10.” And I kind of insulted him.

GILBERT: Yeah, he was real quiet and staring Jaime down. [Laughter.]

JAIME: And a lot of those guys, my heroes, I wouldn’t know what to say to them. I’m not going to say, “I love your work.” Of course I love their work. All the love is in looking at their work. Being with them, I just want to hang out with the guy. I just want to be their friend and stuff. Yes, I mean they are gods to me. Maybe they want to hear it. If they do, then I’ll give it to them. But sometimes those guys just… “Talk to me like a human, here! All I get is you kids going, ‘I really love your work.’ You love my work. Do you love me?” [Laughter.]

NADEL: How is it for you guys these days? I was curious…

HODLER: Do you get too much fan-worship, or?

NADEL: Fan-worship, but also I was thinking like just this past weekend. Since the early ‘90s you’ve been kind of in there with Clowes. It’s interesting to see you kind of in that SPX environment and thinking about how you’ve been canonized. Are you comfortable with your company? Obviously you’re comfortable with Clowes.

GILBERT: Mmhmm, sure.

NADEL: And Pete Bagge, who’s not really being recognized like he should be.

GILBERT: Of course. He's also a fine singer/songwriter musician, too.

NADEL: But are you comfortable with Chris [Ware] and Adrian [Tomine] and Francoise [Mouly] and —

GILBERT: Oh, yeah.

NADEL: I mean, does the grouping make sense to you?

GILBERT: Well I’m good with Bagge and Adrian and Ware. We know those guys. It’s ‘cause we’re all in this sort of common ground, so everybody immediately got along with each other, immediately. There haven’t been any weird guys who I liked but couldn’t get along with. They’ve all been kind of, “Hey, yeah, what’s going on?” “Hey, did you go to that Devo show when you were a kid?” “Yeah, yeah.” Everybody kind of has that same background, roughly. But I have a little trouble with the Raw quotient. [Laughter.] They have trouble with Love and Rockets.

HODLER: What is the history of that? Were you ever asked to be in Raw?

GILBERT: Yeah, but it was more like … it was like a Marvel or DC situation. Like, “You’re going to work for Raw now. You’re going to be in the big time.” Here’s your big time. [Gestures.] [Laughter.]

JAIME: So Gilbert and I kind of set up our own ground where we go. We go, you love Raw? Raw’s East Coast? Love and Rockets is West Coast. And they go, “So West Coast is primitive and old-fashioned?” Fine. It’s not art school. But at the same time [Gilbert begins to interject] — wait, let me cover my ass here. [Laughter.] But at the same time, Raw had Charles Burns. I was introduced to Charles Burns through them. I love Charles, and I love him as a person, because we just hung out with him and he let us do laundry at this house. [Laughter.] But just the whole thing about like, “This is the new comics, and what you thought was comics is out. This is the new thing, this is moving forward.” Well guess what? A lot of your artists liked old comics. The publishers liked old comics. I don’t know, maybe I’m making too much of it. But it just seemed to separate us all.

GILBERT: Well, it was all about competition. And this is what happens with waves of newcomics. Because there’s always separate camps that don’t know the other’s doing. And then they all come out at the same time and it’s like, “What happened? I was doing this by myself! This guy did a comic too! And that’s getting attention! And this guy did too!” That’s what happened with us and the semi-mainstream, like American Flagg and The Rocketeer.

NADEL: You got lumped in with that.

GILBERT: Yeah, because we all came out at the same time, and we immediately became friends with Dave Stevens, who got it, and we got Rocketeer. But otherwise it was weird, a lot of butting heads and “No, we’re the new comic!” “No, we’re the new comic!” “No, we’re the new comic.”

NADEL: And now? It seems it’s all settled, everybody’s happy?

JAIME: Yeah, but for a while there —

SANTORO: But how do you guys feel about being left out of the Chicago?

GILBERT: Oh, that’s … I’m not surprised. It’s OK to have Crumb representing the crazy sex fiend artist, but we can only have one. And he's famous.

NADEL: You think that was it?

GILBERT: We can’t have Gilbert Hernandez there. Who knows? And we can’t have Jaime Hernandez there, who draws better than everybody. [Laughter.] I heard a question like, “Where are all the black people?” “Black people? Whatever happened to the two Mexican guys doing it for 30 years?” [Laughter.] Oh, maybe because we’re the only ones that do comic books regularly. There’s that too. We’re always there. We’re taken for granted because we’re always there. I don’t know. Maybe they just didn’t want us there or they just don’t like us or we’re just not arty enough or pretty enough, I don’t know.

NADEL: Did it bother you?

GILBERT: Fuck no. I didn't even know it was happening.

NADEL: Oh really?

HODLER: I had assumed that you’d been asked and decided not to go.

GILBERT: No. That’s happened in the past, but if we were asked early on and I just kind of dismissed it. But I don’t remember being asked for this one.

JAIME: No, I would have remembered. [Laughter.]No, no, because I go by the city, like if they would have asked me and I said no, I would have thought about like, “Oh, I haven’t been to Chicago in a long time.” And I don’t remember anyone from Chicago contacting me in the past 20 years.

GILBERT: But there’s no camaraderie really between cartoonists. Because not one person mentioned it to us. None of the guys that were there mentioned it to us at SPX. “Hey man, you should have been there." Nobody.

HODLER: Maybe they felt weird about it.

GILBERT: But they could have said something. Because I would. Well I guess I’m the only one who would. “Hey dude, you should have been there. Those people sucked.” I would have said that. But nothing. It’s like forgotten. But it’s not that important to us to do that kind of stuff. I’m really more interested in getting a better job, truly. Because my stuff’s going to come out anyway, awards or not. PowerPoint or not. That could be dangerous, I shouldn’t ignore that stuff. I don’t want to become a recluse like Ditko.

NADEL: You’re pretty far from Ditko. [Laughter.]

GILBERT: Well that’s not what that last Comics Journal review said.[Laughter.]

HODLER: Just don’t read The Comics Journal, then.

NADEL: Stop reading The Comics Journal.

SANTORO: So when we were traveling around this week there was something you mentioned, Jaime. I can’t remember which signing it was or little interview bit, but you were talking about … oh I think it was at the Philadelphia thing, they showed a slide from “100 Rooms,” and you started talking about the 9-panel grid of “100 Rooms.” And you said that Alan Moore really liked that grid and that he was going to use it for Watchmen. And I had never heard that story, so I thought I could just ask you to riff on that a little bit.

JAIME: Yeah. It’s basically what you just said. I mean, it was that simple. In an interview or something he just said, “I really love the story '100 Rooms' and I love that grid. So we used that for Watchmen.” He just said exactly what you said. And after that, that was it. Of course in the back of my head, Watchmen became legendary in the comics circles and stuff. And I thought, well, guess what? At the time when he said it I go, “You’re going to use this 9-panel grid? Anyone can use a 9-panel grid.” It wasn’t the —

GILBERT: It’s not a fancy grid. I mean, it wasn’t magic.

SANTORO: Right, but I’m just fascinated with grids, as many people know. [Laughter.] But I think you both use them to great effect, and I think that’s something like, Peanuts is a grid. 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4. There’s a rhythm to it. And so the rhythm of the 9-panel grid is very interesting, because it creates a center panel, and I think one of the compelling aspects of Watchmen is that center panel. Everyone can use a 9-panel grid. But I just had never heard that bit of comics trivia before. And so I just wanted to get that on record.

GILBERT: Yeah, but you see, Alan Moore’s a different kind of thinker. He’s a total tech-head in the way that he’s thinking about the grid, he’s thinking about where certain images are going to be placed in the grid and stuff. And usually it’s a grid of convenience. It’s like a beehive. You get the most art's worth of comics on the page with a 9-panel grid, really.

SANTORO: Yeah, you do. Especially for the comics format. Like the wider magazine format doesn’t work as well, because you get thinner, thinner panels if you do 3 tiers. And then like the 4-tier, 8-panel grid works a lot better with the magazine format, and you guys have been using that to great effect, I think.

JAIME: Yeah, but it’s only 8. And the 9 is one more.

SANTORO: A center, yeah.

GILBERT: And what’s good about the 9-grid is it’s taller, because we like to draw our characters’ clothing — their shoes, their pants, the women’s legs. Whatever is important for the panel. And you can do that with a 9-panel grid. With the 8-panel or even the cinemascope one I did, that’s tougher. I did a lot of talking heads in that.

SANTORO: When you did Love and Rockets X, but it’s where about you reformatted. You had a 9-panel grid.

SANTORO: When you did Love and Rockets X, but it’s where about you reformatted. You had a 9-panel grid.

NADEL: Why did you do that?

GILBERT: I didn’t do it. In the old days Fantagraphics would hire any art director off the street. [Laughter.]

SANTORO: Are you kidding?

GILBERT: I am. It was just a different way to get the book noticed.

NADEL: Oh I thought this was a whole conceptual thing. It was the only Love and Rockets book that wasn’t —

SANTORO: Because it completely changes the rhythm of it.

GILBERT: It does and —

JAIME: I thought it was somebody’s idea to make it a record.

GILBERT: Yeah. Because you can put it with your records, and they were putting out rock concert books that were shaped like that.

SANTORO: But we have to explain this. So in Love and Rockets 19 or 20, there was a story, X, by Gilbert and then it was a 9-panel grid, and then when it was collected, it was collected as a square-bound volume, and then it becomes a 6-panel grid. They rearranged pages. But were you … did you advise on that at all? Did they ask you anything?

GILBERT: Well, I pretty much tried to add pages and tried to make it look … I trusted them to make it work. They ran it by me. I had to agree. I don’t know anything about this shit. I don’t know how to sell books. I’m poor. I gotta trust them. And it actually got attention that way, because it was shaped differently.

NADEL: It did. I remember when it came out.

GILBERT: But it’s like, frankly the way the story was told originally, it’s not the same thing.

NADEL: Right. It’s very different.

HODLER: I remember it getting covered in like magazines and stuff where I hadn’t seen some of the previous ones.

GILBERT: Yeah, yeah. It got the attention.

HODLER: And now in the new edition it’s back to the —

GILBERT: Back to the comic's proportions. It was thinner, too. That was the problem. I think that’s probably what instigated the change. It’s a little thin book.

SANTORO: Now just to wrap up this grid, because I’m fascinated. [Laughter.] No, but really, a few of the most important newer artists these days, like Michael DeForge and Ben Marra, for example, Noel Freibert — they all are using grids. And everybody can use grids. But I just think the way, especially you guys have been using it recently in the new Love and Rockets and everything, and for all of your career, but it’s just like, I don’t know why the younger kids are doing it so much, but it’s just like, I’m just noticing this more, there’s more of a return to traditionalism. But it allows for freedom, because they put like the fixed movie screen. You’re just like fitting in what you can an you’re not like trying to reinvent each page each time. Like Neal Adams kind of stuff. So I just want to hear your thoughts about that. Just any thoughts that come to mind.

JAIME: Yeah, now I use the different grids for different scenes. Sometimes it’s just that I like my characters obviously to have a dialogue once in a while, where they’re just talking. Well that’s where the 4-tier grid comes in handy, because you don’t need so much space for drawing. And you can do it kind of in real time, because you have more panels. Sometimes a person is talking on the phone. They’re not really moving around, they’re like, in the old days I would have said phone booth. But now it’s just like they’re sitting on a couch on the phone. I can use the 9-panel grid because the panels are slim and I don’t have to draw much setting with the thin panels. Just the simple stuff like that. It’s not that much science other than that, other than, they’re going to be talking for a while so the panel should get smaller. Stuff like that.

SANTORO: So it’s like Tales of Asgard backups. There was the other grid. Kirby would always use the 4-panel split, and the Tales of Asgard stuff was always in that. I just like the way these things get delineated sometimes.

GILBERT: And what’s funny about the grid thing is that a lot of times readers and mostly editors get uptight about, say the Asgard grid. Like, well you’re cheating because there’s only 4 panels on there. You must have at least —

JAIME: It’s what Rick Altergott calls panel pussies. [Laughter.]

GILBERT: Kirby's only got 4 panels and there should be 20 panels on a page. Like that’s better art somehow. And I can’t read it 20 panels on a page. Unless I do 20 panels on a page, then it's ok. [Laughter] The less panels, the simpler the art is … it’s like Nancy. You can’t not read Nancy. You look at it and you’re there so fast. Yeah, I always thought that I liked the Asgard grid, because it looked like Classics Illustrated. Because sometimes they had to blast those off so fast, they would put entire thick novels into 44 pages. But some of the artists were real good. Get a copy of one of the better printed versions of The Invisible Man by Norman Nodell. There’s pages where the housekeeper hears sounds, the invisible man going through the hotel, and she looks for him with a lighted candle, and Nodell basically used a stencil and sprayed ink through the holes to contrast the light shining. It is completely brilliant and ignored because it’s Classics Illustrated. “Where’s Batman?” That’s my code for the modern fan mentality: if Batman's not in it, it's not worth anything. “Where’s Batman?” [Laughter.]

JAIME: Yeah, you’re nominated for an award, you’re up against Batman.

SANTORO: Or like fans will be talking to you at cons, and you’re talking, they’re sort of listening, and you’ll somehow say Batman …

GILBERT: And then everything good you were talking about goes away, because now it's about 'real' comics, it’s about Batman. [Laughter.] In the comics biz, if you’re up against Batman, you fucking lose.

NADEL: To come back to your work: Love and Rockets #5 plays explicitly with the movie-reality split.

GILBERT: But it’s a poor movie. It’s not a good movie of Palomar. It’s like they got the rights to do it, and the only reason it got greenlighted is because Fritz decided to do it. That’s all backstory stuff I haven’t got to yet. That’s all going to come out soon, but right now you’re just reading the movie/story. At the beginning of the book, Luba’s granddaughter Killer says right in your face, “They made a movie about it, but not all of it was so nice." She says that right away. And then you get reality juxtaposed with the Palomar movie. And then at the last page you have Luba and everybody talking about the movie. Basically the movie is something that might have happened had we let someone else make a Palomar movie. That was my personal little joke. Although they would've dropped the Fritz character entirely and added Jennifer Aniston.

HODLER: Do you care that people don’t get it at first?

GILBERT: As long as they’re reading the story and get it as a story. I really resisted going into detail about the movie angle, originally. Because I didn’t want to scare people away. “What is that? A movie series? That’s a stupid idea.” So I resisted at first, but now I like talking the movie thing.

HODLER: It reminds me of that old Clowes story where he imagined what it would be like if Hollywood did a movie of Like a Velvet Glove.

GILBERT: Oh, yeah yeah yeah. Same thing. This is how it would be done if somebody else took it. The only link to my movie version being like Palomar is that Fritz is in it. Playing a combination of characters.

SANTORO: Right. Bula. [Laughter.]

GILBERT: Yeah, that should be a flag right there. [Laughter.] But there’s the backstory to that too, which will come out later. Why she’s dressed as a cavewoman and nobody else is — that’s a backstory too.

NADEL: Where is all this backstory? Is it in notebooks?

GILBERT: It’s in a notebook. I’m not sure where it’s going to be revealed, because I don’t want —

NADEL: I’m more curious as to the process of sketching out the backstories.

GILBERT: Oh, backstories are easy. Backstories are child’s play to us. The backstory is the most important to me about these books. I want the reader to enjoy them just as a book and a story, and then the other level is that people want to know, well, how did she get to this movie? Well, that’s coming too. I don’t want to show the back stories just yet because I don’t want my part in Love and Rockets to only be the exposition material for my Fritz books, where I’m explaining all this backstory stuff. I want the stories to read fresh and new, and explain stuff later somewhere else.

NADEL: So you’re just jotting all this down in notebooks and stashing it away.

GILBERT: Yeah. And I keep my notes, like when I’m preparing a book like Love from the Shadows, I save my notes. I don’t throw them away like I used to. I’ve thrown away so many notes and sketches and stuff.

JAIME: It’s mostly in my head. And what I put in the comic ahead of time, that’s kind of the reference I use.

NADEL: So when we’re jumping in the future with these characters, then you can go back.

JAIME: Yeah.

SANTORO: Or when you talked about the three missing years of Maggie like that was something way back in history.

JAIME: That was all in my head forever.

SANTORO: Yeah and then there was the other sibling and then remember I think you said in the interview this weekend, “There’s only five! No wait, there are six!”

JAIME: Yeah, Calvin from “Browntown” came out by accident from a fuck up. Actual fuck up where back in issue 7, it’s that Locas story where Speedy’s talking to a friend about Izzy, like what a weirdo she is. Well he said, and then she went to Mexico, then she came back weird while people asked, “What happened in Mexico?” That became “Flies on the Ceiling.” In that same story he said, “And then Maggie moved away for three years.” And in the panel, these two women are talking about it. And then someone, one of the women says, “I had six kids, too. And that was hard.” I can’t remember exactly what she said. Well, when I was creating Maggie’s family, when I finally said, I need to show her family. I never have family around. You knew her sister Esther, but you didn’t know she had all these brothers. Well I did that story where she goes to a family reunion and there’s her family, and I do everything. And then I realized I created five. And then I went back and read and she said six. And I went, “Shit!” You’ve got a missing sibling. And so at the last minute I have her brother. Esther’s complaining that two of the boys still live with their mom but they’re grown men and stuff like that. And then she’s saying, “But I moved away. Maggie moved away.” And then the youngest brother pipes in and says, “Or there’s Calvin, who ran away at 16.” Because he shot somebody or got some girl pregnant. And I thought, “OK, she’s got a troubled brother.” And that’s what kind of led to “Browntown.” I had to show, OK … it was kind of my duty to fix this. Show that she had another brother. And that’s why this story is about how he got into trouble, basically.

HODLER: And when did you move to Las Vegas?

GILBERT: About ten years ago.

HODLER: Why did you move?

GILBERT: Uh, well, we had a baby. She had a heart condition, and our landlords sold our rented house to this cretinous, evil person who wanted to turn it into condos. And we had a nice little house. And she would come over every day and say, “Oh, you have a new baby. When are you moving out?” It was like, OK, what the hell. I need a yard for this kid later on. I need something else. And so we started looking around. We were astonished at how hard it was to find a decent place to move. After a while I remember my wife would come home and go, “Well, I saw a crack house that looked pretty good. We should consider that.” [Laughter.] And luckily that was the time there was the boom in housing in Vegas. I was burned out, we were so stressed out, our baby had a heart condition and we were just stressed out about the landlord kicking us out. I said, “Let’s just get the fuck out of here.” But not too far that we can’t come back and visit family if we want to. We lived in L.A., I can’t live in nice town Ohio. I gotta live in a hot place where it doesn’t snow. And if we’re really bored we’ll go to the strip and party out and come home after that. So we started looking around and we were of course like, holy shit, there’s nothing here but dirt and rocks. I’m going to go mad. And then we checked out the neighborhood, and it was literally near a mountain and it was awesome. There’s a mountain all by itself and that area was being built really fast. By the time we got there there was a market and everything else we needed.

SANTORO: She walks to school, no? Your daughter?

GILBERT: No, she takes the bus.

SANTORO: Oh, but it’s really close.

GILBERT: Close enough. I still had to drive her to school, but it was only because I wanted to. I’m too lazy to walk. It’s close enough.

NADEL: And you get back to L.A. a fair amount?

GILBERT: We used to. Until we started to see the difference of what we didn’t notice before. The intense traffic. When it got to the point where we wanted to take our daughter to Disneyland and it took three hours, and it’s half hour drive from Hollywood without traffic. That’s not living, man.

HODLER: Well you have Caesars Palace there in Vegas, you can just go there. [Laughter.]

GILBERT: Yeah, yeah. Or to similar things.

SANTORO: When did you move to Pasadena, Jaime?

JAIME: Um … God, maybe about the same time he moved away I met my wife, and she lived there. And we were dating, and she had a little girl, a little one and half year old, and we fell in love, blah blah blah. And let’s see, should I live in her house that she’s buying, or should I live in my apartment? Hmmmm, what should we do?

NADEL: How has raising daughters changed … has it changed anything in the work? Noticeably?

GILBERT: Not noticeably. Nothing in my work is conscious. It comes from the unconscious or subconscious. And really I never think about ... except for losing sleep with having a new kid, which was about the first six months… that kind of thing. You can add that to a story. But it never really is a conscious thing. I’m always thinking about kids and babies, even when I didn’t have one.

NADEL: Hmmm. Really?

GILBERT: Yeah. Because of growing up in that environment. There was always kids and babies. I remember you [Jaime] were lamenting once, before we started having kids. He goes, “There’s no more babies. We don’t have babies in our life anymore.” Because there was always babies and little kids, always. And then there wasn’t for a long time. And then we were having babies and stuff. But that’s why it’s normal in my comics. So now I’m really focused on making a living seriously. That’s the thing that’s changed. I really take that seriously. There’s no room for being lazy anymore ever again. [Laughs.]

NADEL: Were you ever lazy?

GILBERT: Yeah. Lazy in the sense that, oh, I haven’t done Love and Rockets in a couple of ... weeks? I’m serious, that was back in the day. When you get older, time passes faster. I can’t do that anymore. I don’t take it for granted. Gotta use that time.

NADEL: Are you both putting out more every year than you used to? I guess you are.

JAIME: We’re putting out something like four more pages than we did in the small Love and Rockets. So, it’s about the same. I think Gilbert’s doing more work than —

GILBERT: Yeah, I just gotta make those bills at the end of the month. So I do Dark Horse comics and others as well.

NADEL: They give you a page rate or something?

GILBERT: They just pay me a flat something-something-thousand an issue. They're easy to work with. Never had a problem with them.

NADEL: You’re just with Fantagraphics pretty much, except for the art book.

JAIME: Yeah.

NADEL: Has there been any blowback from working with other publishers and stuff? Or has it been all right?

GILBERT: Um, I guess Fantagraphics might not be so crazy about it, but they know I've got to pay bills and all that.

SANTORO: I just want to hear a little bit about Fatima. I really like Fatima. I had noticed in the comics store that I work at, Copacetic Comics, there’s a lot of new readers picking that up. It’s pretty interesting. It might be just the zombie thing or, not sure, but the covers have been really striking and really interesting. Was it always a zombie story? I remember you saying it was something else earlier. I can’t remember.

GILBERT: It was a transmogrified spy story. I wanted to do a spy story that I could do a series of. But I didn’t have a lot going on. What would the drug war be like in the future? I was kind of was toying with that idea. But I didn’t have a lot to go on it. Because when you pitch your stories, especially to a place like DC and then Dark Horse, they want to know what it’s about and I suck with pitches.

NADEL: Oh Dark Horse does that as well?

GILBERT: Not as much as anymore. Can't really blame any company that wants to know where their money's going. I have Diana Schutz on my side, and she knows what I’m going to do. Diana really looks out for me.

SANTORO: So it was a spy story, and now ...

GILBERT: It was a spy story that I had laying around for a long time but no place to put it. I thought, “What’s going to goose this? What’s going to get me, not just me but the readers, all goosed on this stuff?” I’ve done superheroes, failed. I’ve done this, failed. I’ve done that. Can’t fuck up zombies. It was as simple as that. And I love showing zombies getting blown up. I mean it’s literally this 12-year-old boy mentality. I said well, if I just apply that to a cool series about ... and I’ve never really had action stars that just kick ass and shoot guns and ... I’ve never done anything like that.

GILBERT: It was a spy story that I had laying around for a long time but no place to put it. I thought, “What’s going to goose this? What’s going to get me, not just me but the readers, all goosed on this stuff?” I’ve done superheroes, failed. I’ve done this, failed. I’ve done that. Can’t fuck up zombies. It was as simple as that. And I love showing zombies getting blown up. I mean it’s literally this 12-year-old boy mentality. I said well, if I just apply that to a cool series about ... and I’ve never really had action stars that just kick ass and shoot guns and ... I’ve never done anything like that.

(Continued)