From The Comic Journal #285 (October 2007)

When we speak of success in the context of serious comics we are usually talking about a few good reviews and modest but sustainable sales figures. The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation has achieved another level of cultural signification altogether. Time magazine, NPR, The Today Show, The New York Times — over the past 12 to 18 months, Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón’s graphic adaptation of the most talked-about government report in a generation has attracted glowing notices from radio, television and mass-circulation magazines and newspapers. The book adeptly transforms the formidable Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States into a reader-friendly comic book. It has been nothing less than a national bestseller. Its success benefits from and contributes to a larger ongoing revaluation of comics. The book has also turned its creators into mini-celebrities.

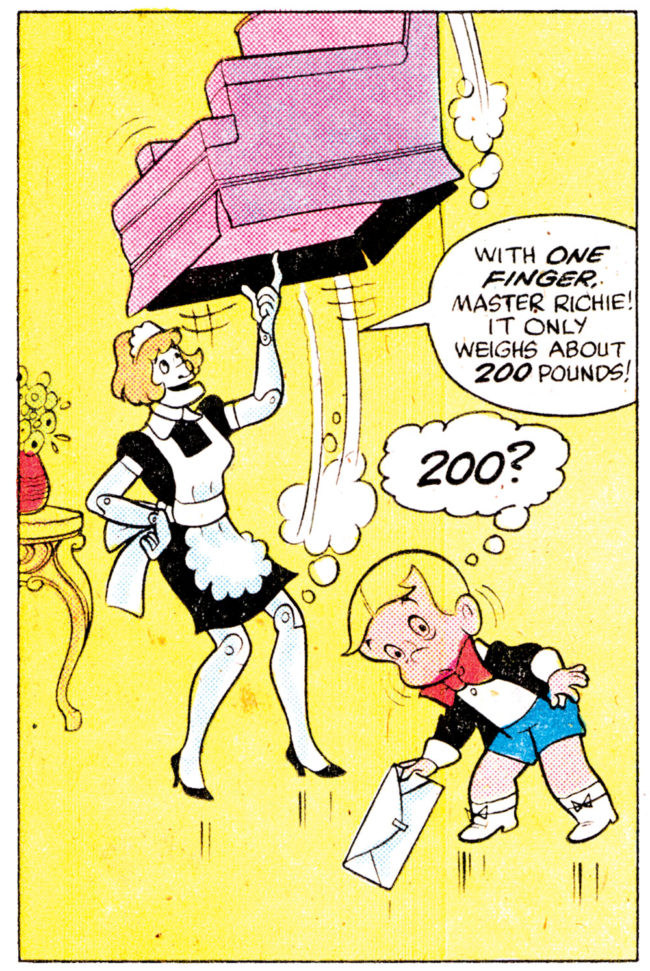

Colón has paid his comics dues many times over. He was born in 1931 in Puerto Rico and has been a professional cartoonist since the 1950s. His first job was working as an assistant to the legendary Ham Fisher, the troubled creator of Joe Palooka. He started working for Harvey Comics shortly after Fisher committed suicide in 1955. Colón was 24 years old at the time, and he would end up staying at Harvey for 25 years, drawing such iconic characters as Casper the Friendly Ghost, Richie Rich and Wendy the Good Little Witch.

At Harvey, Colón became close friends with the writer and editor Sid Jacobson, his future collaborator on The 9/11 Report. He also grew attached to Warren Kremer, whom he refers to as his “mentor” and as “the great architect of comics.” Almost all of Kremer’s work was for Harvey, which may help account for his relative obscurity in comics historiography. According to Wikipedia, when Warren Kremer once visited the Marvel bullpen, Marie Severin said, “They don’t know it, but this is the best artist who ever walked through these doors.”

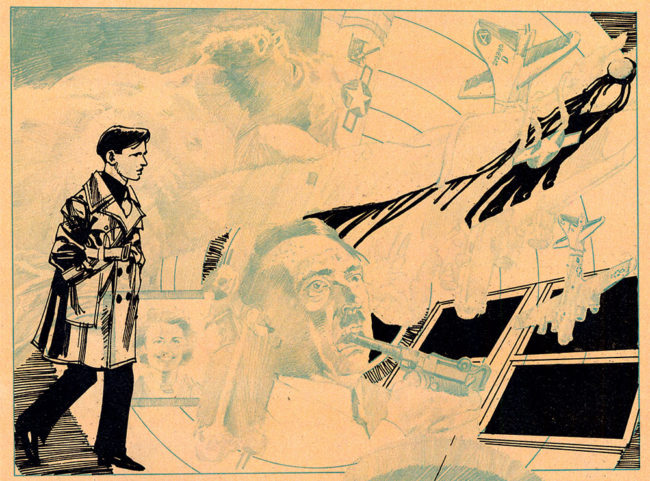

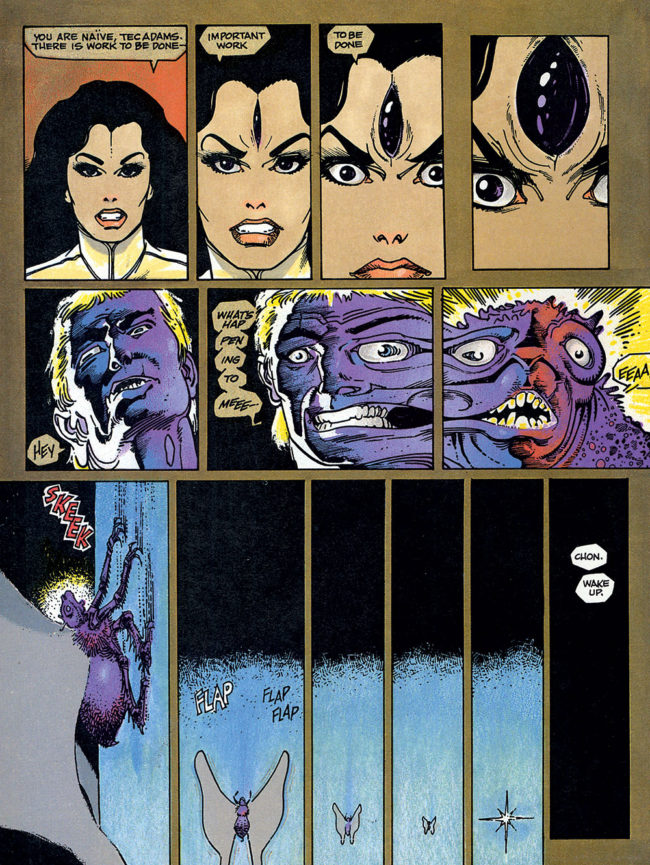

By the late 1960s, Colón was looking to expand his repertoire. He proved more than capable of shifting gears for different publishers. As a freelancer, he drew stories for Creepy, Vampirella and Eerie from 1969 through the early 1970s. Warren’s horror line represented a sharp break from the kid-friendly optimism of the Harvey titles, as did the stories he drew for Heavy Metal in the early 1980s. He drew Grim Ghost for Atlas/Seaboard in the mid-1970s, Air Boy for Eclipse in the late 1980s, Solar: Man of the Atom and Magnus, Robot Fighter for Valiant in the early 1990s, and Strip Search for Eros in 2002. For many years he worked as a freelance illustrator for various magazines and book publishers.

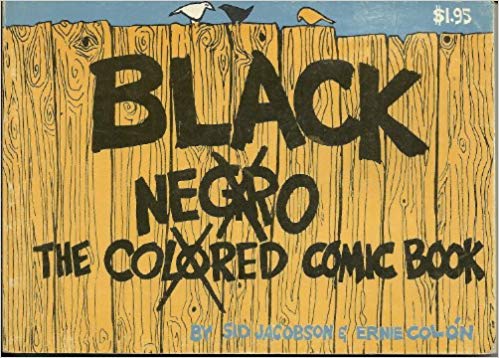

One project that has almost completely disappeared down time’s memorial hole is The Black Comic Book, which Colón created with Sid Jacobson. Published by Price/Stern/Sloan in 1970, this 80-page paperback satirized superheroes and comic-strip characters, “with the hope that one day, in a world of greater honesty, justice, and understanding, the black man will take his rightful place in literature of all kinds.” The book was originally priced at $1.95. The only copy that Amazon lists is used, and is available for $93.03, with free shipping.

Colón broke into the Big Two in the late ’70s. He was hired by Jim Shooter in 1978 to work on John Carter: Warlord of Mars, and he later drew Marvel coloring books and a couple of graphic novels, one featuring Black Widow. As a Marvel freelancer, he came up with the idea for Damage Control with Dwayne McDuffie. He also contributed to a handful of kids’ comics that Marvel launched in the mid-1990s in a short-lived effort to recruit younger readers to the Marvel brand.

For just over a year in the early 1980s, he set freelancing aside to work at DC as a full-time editor. The experience does not seem to have been a career highlight. But it makes sense that he worked for the big comics companies as well as for Harvey, Warren and several smaller companies. Colón is a savvy, professional, hardworking and highly adaptable cartoonist whose work ranges from comedy, horror and fantasy, to adventure and sober nonfiction. He has sustained a decades-long career in comic books without drawing very many superheroes. It cannot have been easy.

Interviewing Colón for the Journal was a lot of fun. The bulk of the interview was conducted by phone; we spoke for nearly an hour on each of three separate occasions in June 2007. Ernie is funny, accessible and personable, and he has an appealingly matter-of-fact speaking style. He also very kindly responded to several long emails. Once the Journal pays me, I will blow my wad on a complete run of Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld, which he drew for DC in 1983-1984. And no, I won’t lend them out.

STARTING OUT

KENT WORCESTER: What were you doing before you started out in comics?

ERNIE COLN: I was a messenger boy, and I worked in factories. I worked in a glass-etching place, and a sheet-metal factory. We made Kotex dispensers for subway station restrooms.

Was this in New York City?

That factory was in Long Island City. I had arrived in New York City with my mother and siblings when I was 10 years old. The biggest shock I experienced was when we first arrived to the city. It was on a ship that slid into New York harbor, and this gust of wintery wind hit us hard. I had never experienced that kind of cold before. We all spoke Spanish, of course. I had some English, but I hadn’t mastered it. I don’t know if I’ve mastered it now! We did study English in school back in Puerto Rico, but I wasn’t fluent. When I arrived they put me back one grade. I pretty much caught up that year and was back on track. It was painless. I hate to put my experience on anyone else, but I’m not convinced that it’s beneficial for kids to have bilingual education.

What did your parents do for a living?

My mom worked in a textile sweatshop; for a while, she worked at a factory that made plastic handbag handles. My dad was a detective, but he stayed in Puerto Rico. They were divorced. Later in life, my mother became a bank teller, which is a much nicer life. And my stepdad worked for the Post Office. My stepdad was a pretty conservative guy, and my mom was pretty liberal. I was a damn pinko when I was a kid, and probably still am.

We started in the Bronx, and then, when my mom married my stepdad, we moved to Williamsburg in Brooklyn. I was too light in the south Bronx and too dark in Brooklyn. For high school, I attended the School of Art and Design, which was then called the School of Industrial Art.

I knew what I wanted to do when I was about 6, which was to draw comics. I was absolutely in love with the Sunday funnies, and I wanted to draw them. In Puerto Rico, we read La Prensa and El Imparcial, and they both reprinted American comics. In New York, we used to get both the New York Daily News and the Mirror on Sundays. My stepfather also read the Times, the Herald Tribune, and the World-Telegram and Sun. As a teenager, I read the afternoon paper PM, as well as the journalist I.F. Stone’s newsletter, I.F. Stone’s Weekly.

Have you ever thought about moving back to Puerto Rico?

Over the years, I have returned to Puerto Rico about three times. I’m so assimilated that the experience was not that meaningful to me. I have about eight sisters; they are scattered all over the place. One is in Utah, and a couple of my sisters still live in the Caribbean.

Was it the movies that gave you a love for storytelling?

I was a huge movie fan. Still am. My grandfather in Puerto Rico owned three movie theaters. So I went to movies every single day after school, and I went in for free, of course. When I moved to the U.S., I was able to go to the movies twice a week. I’m also a book reader. I’m omnivorous. I read everything — biography, fiction, mysteries, history — and with movies, it’s the same, from comedy to drama to science fiction. The latest film I enjoyed was Pan’s Labyrinth — it’s a great film that I would happily recommend.

Even though I have always enjoyed reading books, I was too much of a wise guy in high school to go to college. I really didn’t like school and I didn’t want to spend any more time in the classroom. Later on, I had some regrets about my decision. At this point, I’m something of an autodidact, but I still feel there are gaps in my education.

What sort of comics did you plan on creating when you were just starting out?

The adventure strip was big when I was growing up — Terry and the Pirates, Dick Tracy, Steve Canyon, and so on. When I read the newspaper strips I read everything but Little Orphan Annie, which I really could not stand, but I was particularly fond of adventure stories. So my mind was focused on comic-strip adventure stories. Over the years I tried out a bunch of comic strips, but the older I got, the more out of fashion the adventure strips became. My timing, as well as that of my generation of cartoonists, was unlucky. The adventure strip was fading, while gag-a-day strips were in the ascendancy. So I decided to try my hand at comic books.

Before I arrived at Harvey Comics, a friend of mine put me in touch with Ham Fisher, who of course was the creator of the comic strip Joe Palaooka. I inked in his backgrounds for about a month — until he committed suicide. This was my first real cartooning job. He was having a horrendous feud with Al Capp, and he was drinking a lot. But Mr. Fisher was very kind to me; he was very friendly and encouraging. His assistant was Moe Leff. Weirdly enough, his brother, Sam Leff, used to do a rip-off of Joe Palooka called Curly KO.

HARVEY COMICS

How did you land a job at Harvey Comics?

I applied as a letterer. It was soon evident that I couldn’t letter. But they saw I could draw, so I got a job in production and practiced the characters at home at night. A year later, I started drawing Richie Rich, Casper, et al.

Can you say more about the work you did for Harvey?

Harvey Comics were very popular in the 1960s and early 1970s. Richie Rich was selling in the millions. At one time there were 33 titles under the Richie Rich label – comics about his aunts and uncles and so on. Thirty-three was probably too many titles, though. [Laughter.]

My editor during my years at Harvey was my friend Sid Jacobson, who had a real feel for the characters. Of course, Harvey was run as a family business. One brother died — Robert — and the other two brothers, Leon and Alfred, looked after the company. But it was Sid Jacobson, Lenny Herman and Warren Kremer who kept that place humming and profitable. The brothers’ intense dislike for each other — at odds with their fraternal twinship — led to bitter acrimony. They kept the lawyers happy and well-fed. They essentially sued each other into bankruptcy. The Harvey line-up would be just as viable — if not more so — than Archie if the succeeding owners would have published them.

Leon and Alfred would put their arms around their artists and say, “Don’t worry, we’ll look after you. We will even set you up with a pension.” That of course never happened, but the atmosphere in the office was extremely friendly. Also, they liked my work. They never asked me to revise my pages once I turned them in. Also, they would pay the artists as soon as we turned in the work. No delays. I once complained bitterly when it took them 30 minutes to cut me a paycheck.

I drew a lot of pages for Harvey. I drew somewhere around 15,000 pages for them. My favorite character was Richie Rich. He had the potential to be another Tintin. He was an adventurous boy with a lot of money. The early stories emphasized how much money he had — how big his piggybank was, his pool, his house, and so on. I can take credit for steering the character toward adventure stories. My attitude was, “Let’s show what the money can do.” He can use the money to travel — he has his own jet, after all. I wanted to turn him into a world traveler. We even sent him into space — I remember a couple of covers where we showed him in a spacesuit or a rocketship.

Did you ever feel that your work on Richie Rich was in contradiction to your political views? After all, he lives in a kind of capitalist paradise.

The fact is that the characters dictate their environment. Surely this produces the best kind of fiction. The attitudes are only what one aims for in dealing with children’s fiction — moral values, the good are rewarded and the bad brought to account. All those wonderful values that are so often overlooked in later, real life.

As for the character’s vast wealth — yes, well, wealth is usually in the possession of a privileged few. That’s nothing new. As it happens, I still retain a healthy store of lefty ideals — if that means I empathize with the poor, the disenfranchised, etc. Were I a gnat, I would love to bite the ass of every dumb-ass politician whatever their party or persuasion.

Did you enjoy working on Casper?

The problem with Casper was he was so simply drawn. If you were off by a little bit you were really off. Warren Kremer, the great architect of comics, had a real flair for rendering Casper. This meant anyone who followed in his wake suffered by comparison.

With Harvey stories, you had to stay “on model.” Of course, that depended on the ability of the maintenance men. That’s what we were. We were taking care of the characters. We had to make certain that the stories were appropriate to a particular character or set of characters. The same goes for how the character looked on any given page. Warren set the standard and the rest of us tried to keep up. I tried to get as close to Warren Kremer’s style as possible.

There were a few characters who got a lot of play who I thought were silly — Little Dot, for example. Then there were characters who showed some potential. Hot Stuff, Spooky the Tuff Little Ghost and Wendy the Good Little Witch were all good characters. Richie Rich, of course. Part of the secret to a good character is good side characters. Richie Rich had great side characters — Cadbury the English butler, Chef Pierre, Dollarmation, Irona the Maid.

What about the bad guys?

The villains in Richie Rich comics were usually kidnappers or mad scientists. I don’t think there was one evil genius who was running things behind the scenes. I created one character I liked called Timmy Time. He and his damaged robot — called Traveler — went from one time-space zone to another. Again, my idea was to expand the horizon. It didn’t go anywhere. There was only one issue. They didn’t go any further with it. I guess the current owners of Harvey own the character.

In the meantime, Al had ideas like Billy Bellhops — probably the nadir of Harvey Comics. Sid Jacobson once remarked, “Yeah, what every kid wants to be — a bellhop!” We also had a character called Fruitman. It had something to do with fruit but I couldn’t possibly give you any details.

The reason why the people who own the Harvey characters don’t publish comics with these characters is beyond me. But it was fun work. It was at Harvey Comics that I met Sid Jacobson, one of my oldest and best friends. I also became good friends with Lenny Herman, the writer. But Warren Kremer was my mentor. He was about 10 years older than me, and he was a marvelous cartoonist. I call him the architect of comic books because he used space better than anyone else. And he was an open book. Whatever he had to offer he wanted to impart it. Warren pretty much designed all the characters for Harvey — even Casper, which the company got from Paramount, didn’t have legs until Kremer put them on. He also decided to drop all references to Casper’s being a little boy. From that point on he was simply a ghost.

But Warren only worked at Harvey, and Harvey never gave any credit to its writers and artists. You weren’t allowed to sign your work at all. That is a major reason why Warren Kremer’s name is not better known among fans of comic books.

Did you ever try to sneak your name into the artwork?

Every now and then, in the details on a theatre marquee or something like that, Warren would put my name or I would put his name, but no one ever noticed. I also caricatured political figures every so often. For example, I used Nixon as a villain in a Harvey comic. The Harvey stories weren’t political, of course, but focused on lighthearted comedy and adventure. I was always opinionated, but I didn't try to express my ideas in my work for comic-book companies.

I left Harvey before it closed down in the early 1980s. I finally decided that I needed to move on after 25 years. For most of my time there, I was making 15 bucks a page — everyone was, including Warren, who was a mainstay of the company. At one point, I asked for a raise but was turned down. And so I tried my hand at something else.

In fact, I worked in multimedia events for a year — largely corporate events with live music, film, slides, or even speakers and dancers. I made good money doing the storyboards and some producing. Then, one day, there was no business anymore. It simply disappeared, partially because of PowerPoint and partially because corporations were looking for ways to reduce their costs.

Harvey Comics called me roughly a year after I left, and offered me 30 bucks a page, which was a lot of money in those days. They were desperate because the Richie Rich and Casper titles were doing quite well and they needed to fill a lot of pages. But I thought that it was unfair that I was making twice as much as the guy who had mentored me. I tried to tell Warren about this so that he would ask for a better pay rate, but Warren didn’t want to know.

COLLABORATING WITH SID JACOBSON

I recently found out that you collaborated on a book with Sid Jacobson in 1970, called The Black Comic Book. In the book, you make fun of comic books and comic strips for their Caucasian-centered perspective. Could you say something about how that project came about?

Good lord — 1970. Well, the publisher took us to lunch at the Algonquin and Sid and I thought we were set. The book sold well, but not fantastically. We also appeared on the Joey Adams radio show. He was a Broadway-type of guy — the kind you expect to have a half-chewed 25-center stuck in the corner of his mouth while talking out of the other corner. He gave us a demonstration of the Jekyll-and-Hyde phenomenon.

His greeting to us was, “What’re you guys gonna talk about?” Before we answered, he went on rapid-fire: “You better know what the hell you’re talking about, ‘cause I can’t help ya, unnerstand?” He then disappeared into a door with no name. A few minutes later, given enough time to chew on three or four nails, we were led like calves to certain death in a dingy paper-strewn studio. He shuffled a few papers without looking at us. We sat like oddly posed mannequins in a Stephen King show window.

And how did he begin? “Hi, folks, it’s Joey Adams, bringing you the best in the entertainment world. Today, I have two fine young men who are going to talk about a magnificent book they …” He went on like that — bright, optimistic, a commercial for an arthritis-free life. Soon as it was over, he turned from us as a divorced man turns away from his ex-wife before she spots him, while his secretary — the Crypt Keeper on a bad day — showed us the door by pointing a bony, spotted finger at it. That was it. That was our roughly nine seconds of fame.

But the timing was good. There were hardly any African American characters in comics — Ebony in The Spirit — but many people objected to his looks and his speech. At Harvey, we had a little boy named Tiny in one of the books and he was popular. Sid also included people of color in quite a few scripts. So The Black Comic Book was a take-off on how African Americans were not included in comics. Since then things have changed for the better. I don’t think it would be relevant now. But we’re very proud of that book. It was a nice, funny kick in the ass to the industry.

COMICS IN THE 1970s

If the information on the Internet is accurate, you worked for Larry Lieber’s short-lived rival to DC/Marvel, the Atlas/Seaboard line of comics in the mid-1970s.

My memory of Atlas is a little hazy. But I know that that is where I met Marv Wolfman, who later was my roomie at DC Comics when I was as an editor there. I also worked with Jeff Rovin at Atlas. He was editor-in-chief at 19 or 20 – a wunderkind, definitely. He was sharp and very knowledgeable. Not stuck in his present. A real time-tripper when it came to appreciating the value of past crafts and artistry in movies, music, any of the arts. We had a stellar group at Atlas, including Howie Chaykin, Neal Adams, Steve Ditko and so on. I also drew a few issues of Airboy [for Eclipse].

What are some of your recollections about working for Warren Publishing in the late ’60s and early 1970s?

Warren was a weird place to work. You didn’t know what was happening from one week to the next. On the other hand, with Warren, the process of creating the artwork was a little more exciting, because you were encouraged to experiment. I did a lot of things with my artwork for Warren that were time-consuming and that would have been a lot easier if computers had been available. But it was fun to try new things. The editors sometimes let me write my own stories, and they gave me a lot of freedom as far as my drawings were concerned. With Harvey, things were a little different. The office was more tightly organized. But sometimes I would have fun with the story when I worked for Harvey Comics. At the same time, sometimes the stories became mundane.

Once I tried an experiment where I drew 23 pages in 24 hours. I only got up to go to the bathroom. I set a record for myself. In that case, speed was more important than anything else. By then, the characters were so ingrained that it wasn’t that hard to compose a page and do it quickly. But I never did that many pages in a day again.

Did it bother you to work on books that were relatively violent after working at kid-friendly Harvey?

I love violence — as long as it’s an inherent part of the story and makes a moral point. Working with Jim [Warren] was great. As I said, he allowed us to experiment and write our own stories. He was a true character himself. Great guy.

How did being a cartoonist affect your social life?

I’ve never known that many cartoonists. I’ve certainly never been to many conventions – I’ve only been to four, and one of those was for less than an hour. Unfortunately, I’ve also lost touch with people over the years, such as Howie Post, who I would love to see again. Fortunately, I was never embarrassed about being in comics. At parties, I would be introduced to a lawyer, a dentist, a lawyer, a dentist. When it was my turn to be introduced, people would always perk up. Even today, people like to ask me about my work. I often get asked if I’ve drawn something that they might have seen. When I tell them I used to draw Harvey characters like Casper and Richie Rich, they become very excited. Many people have a strong connection to those characters. So being a cartoonist was never something I felt shy or embarrassed about.

My family has never made me feel awkward about working in comic books, but none of them are particularly interested in comics, only in my career. I have been married for many years and my wife and I have three daughters. I also have eight sisters. My daughter Luisa is an actress. She is currently the lead in a film called Day Night, Day Night that has gotten great reviews. Amanda works with autistic and disturbed teens and somehow has retained a great sense of humor and optimism. She is the saint in the family. Becky is in high school and writes and paints with talents far superior to mine.

Did you always feel a sense of pride in being a cartoonist?

I always shared Will Eisner’s belief that comics could be something more. I felt this very strongly, from my first years in the business. As far as I am concerned, the only people who tried to put down comics were staffers at DC and Marvel, who would refer to what I did with Richie Rich and Casper as “bigfoot” drawing. That would piss me off. I somehow thought that what we were doing was cartooning.

I only met Will Eisner a couple of times, but as far back as I can remember I thought that comics could be a lot more than simply superhero comics. When I was growing up there were all kinds of comics, from Westerns and romances to kids’ comics. I resented the fact that superheroes became the major genre in comics, and I probably made a mistake when I let people know how I felt at DC and Marvel.

WORKING FOR THE BIG TWO

Which did you work for first, Marvel or DC?

I went to Marvel first. I wrote to Jim Shooter a letter where I drew Casper on his knees, begging to be rescued. He responded immediately and gave me John Carter of Mars to work on. I enjoyed the office environment at Marvel — I was especially fond of Marie Severin. Jim Shooter was very nice to me. I had a little trouble with a couple of writers, but otherwise, it was a terrific experience.

I later did some work for Jim Shooter’s Valiant. Working on Magnus, Robot Fighter was a wonderful experience. I drew him on Canson paper with pen and ink, then colored it with Prisma pencils and acrylics. Jim Shooter was a joy to work with. He used to act out every panel — “he must be in mortal danger every step!” he cautioned. He would put himself in a crouch position in his office, ready to obliterate the next fool ’bot daring to face him.

Of course, I knew Jim from Marvel, when he was top man there. That was when he formulated the New Universe. It was a great idea and had it been given the work and dedication it deserved, could have been a mainstay in the Marvel canon. Instead, his ideas were nitpicked and botched by grousers and moaners who didn’t have the imagination to see the possibilities in developing them.

It wasn’t easy to switch from kids’ comics to superhero comics, at least not at first. It was a question of lots of sweat and making lots of bad drawings. It took work. But after a while, I got used to the expectations at the big companies.

When I think back to my time working with DC, I can think of three particular highlights. One was Amethyst, the second was The Medusa Chain, a graphic novel [published in 1984] that didn’t many sell any copies, and the other involved working on Underworld, which was written by a guy named Robert Fleming. He was a young fellow who I thought showed tremendous promise as a writer. He was not made welcome at DC. A lot of people tried to undercut him and sabotage his career. They would do terrible things just for a laugh, and unfortunately, Robert Fleming was the recipient of their malice.

I also worked as an editor at DC in the mid-1980s — for precisely one year, two weeks and three days. The extra two weeks were so that they could find someone to fill my position. Jenette Kahn had initially hired me and we agreed to try things out for a year. At DC, I was responsible for Green Lantern, Flash, Wonder Woman, Blackhawk, and there may have been one other title. For a while, I was also responsible for responding to young artists who submitted portfolios. It was the first and only time that I worked full-time in a corporate setting. I liked the job at first but little by little I became disenchanted. For one thing, the workload was not reasonable. It was much too much.

Like in any office, there were some politics involved, and I saw things I did not like. There were people who did things that were not — in my view — appropriate. I had a couple of run-ins, for example, with Len Wein, who used to override my editorial decisions. He would insist that he was in a position to do so. He would do that without consulting me at all. He wouldn’t even have the courtesy to ask me what I thought. An egregious example of this: I had talked Alex Toth into doing a Green Lantern story. He did beautiful work. The story went to the production department, and I found out — after the fact — that Len Wein had taken scissors to the story so that the continuity was more to his liking. Here’s the problem. It’s a compound fracture. Number one, he didn’t consult me, and I was the editor on the book. Number two, he didn’t ask permission of the artist — a well-known curmudgeon, not to mention one of the finest artists in the history of comics. You would think he would have respect enough and awe enough and admiration enough to call the artist directly. This is the sort of thing that I came up against. It bothered me a lot. I didn’t care for that treatment.

At the same time, I had no trouble with Jenette Kahn at all. I liked her and she liked me. There was no problem with people at the top level; it was people at my level. I got along great with Karen Berger and Marv Wolfman, for example. After I left DC, I had very little contact with the company. I did one or two jobs for them after I left the editorial position, but not so much. It was very definitely a divorce. We were both equally elated to be rid of each other.

When I started working at Marvel on a freelance basis I kept pretty much to myself and didn’t interact with as many people as I did at DC. But I didn’t work for either company for as long as I worked for Harvey Comics. My last work for Marvel was quite a few years ago. I worked on Marvel’s short-lived “Star” line, which was a poorly handled effort to sell Marvel comic books to young kids. It was a great opportunity wasted on rip-off characters and poor scripts. Like I said, the fanboys who later became editors called kids’ books “bigfoot.” This is an ignorant misnomer coined by those who misapprehend the range and plasticity of comics, which is something they take for granted in the movie business.

Were you involved in the effort to push Time Warner to compensate Siegel and Shuster for their work on Superman?

Not really. The guy who was the torchbearer on that was Neal Adams. He did a magnificent job in leading the charge. At the same time, I can say that Siegel and Shuster did sell the character in good faith. In some ways, they did not have a case. But it’s a complicated situation. It is a little like if someone sells you a stamp for a dollar, and then it turns out to be worth millions. If the original seller is broke and starving on the streets, it seems a little inhuman not to give them a little money out of the profits you’ve made. But of course corporations are not people, and they are not motivated by anything but money. Neal Adams and other folks were able to raise enough noise that the company pretty much had to respond.

Were you concerned about the issue of returning original art to the artists when you were working for companies like Harvey, Warren and Marvel?

No, because it was the norm. Everyone was living under the same kinds of rules. It never occurred to me that I should be different. It was only when it became a hue-and-cry that I joined in, and said, “That’s what I want, too.” Not that it did me any good, because I basically gave away every page I ever drew. For two reasons: There were a lot of kids who loved comics, and I enjoyed giving away pages to fans. The other reason is that when you’ve been in the business as long as I have, you are likely to have drawn thousands of pages. It is hard to keep track of that many pages, and it is also hard to store them. Over the years I’ve moved around a few times, and the idea of schlepping piles of original artwork strikes me as somewhat daunting. I’ve also thrown out a few pages that I didn’t like. If I don’t like how a page comes out, I would rather throw it out.

There was one title that I worked on — Richie Rich — where I never saw an original page of art again. None of the artists received a single page from that title, even though they had been promised to us. They were taken from Harvey’s storage facility, and those pages show up from time to time on eBay and places like that. Otherwise, I did receive lots of my Harvey artwork, including pages from Casper, Wendy and Little Dot.

THE 9/11 REPORT

Who came up with the idea of turning an official government document, the Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, into a graphic novel?

I did. I bought the report when it first came out, like about a million and a half other people, but I couldn’t get past Page 50. I couldn’t keep track of the names. And I thought this should be clearer. I called Sid, and said wouldn’t it be great to turn this into an extended comic book? And right away, he said yes. He also raised funds to support our work from a producer named Roger Burlage, who is in the film business. Burlage immediately put up the money — it only took a couple of days. I have never been involved with a project that moved as quickly from the idea stage to the implementation stage.

Some reviewers have suggested that our book was the first of its kind, which is definitely not the case. Educational and nonfictional comics are part of the history of the medium. It was an interesting book to work on, and I am delighted that it has found an audience, but it was not especially groundbreaking in terms of what comics can do. It is a fluid and plastic medium that can be used to tell many different kinds of stories, including true stories.

Fortunately, publishing the book was easy. The first publisher we submitted the manuscript to — Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux — accepted the book immediately. FSG were fantastic. The editor we worked with — Thomas LaBien — saw the value of our project right away. FSG also sent the book to Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton, who of course chaired the Commission and wrote the introduction. Their contribution helped make the project a legitimate undertaking.

Were there any images — particular faces for example — that were particularly difficult to draw?

Some of the faces were easier to capture than others. Michael Chertoff lends himself to caricature. Dick Cheney also has an easy face to draw. But with Cheney, you have to be careful. You want a likeness, not a political statement. Cheney has a natural form to his mouth that looks like a sneer. I tried to stay away from the sneer; I didn’t want him to look like a villain. I tried to make everything look as neutral as possible.

What about portraying people from the Middle East?

That’s difficult. People have strong views about how different groups are portrayed in comics. And some people have criticized how we portrayed Arabs in the 9/11 book. On the other hand, I’ve spent a lot of time researching this topic, and I’ve looked at hundreds or thousands of pictures. A Pashtun Arab has a beard and a robe. That’s just a given. I have tried to stay away from stereotypes, but some cultures have strict rules about things like facial hair and clothes. It’s hard to respect these rules without being accused of recycling stereotypes.

One of the striking things about your 9/11 pages is how varied they are: You shift from high-level meetings to maps to Middle Eastern street scenes.

Part of the challenge is giving variety to the reader’s eye. Going from one talking head to another can get a little boring. It’s always a question of finding the right balance. When you are creating a graphic depiction of a real-world event, you have a balancing act. You have to make the image work on the page, but you also have to be true to the historical record.

Are you and Sid Jacobson working on anything at the moment?

We have several projects lined up with FSG. The one we’re working on right now is called America’s War on Terror. It addresses the aftermath of 9/11, starting with 9/12 to the present day. I am about halfway through that project, and there are projects waiting in the wings. In terms of the War on Terror book, we are not interested in offering editorial opinions, but in showing the reader what has and hasn’t been accomplished since the towers fell.

Let me put it this way. I had this old girlfriend who said I was a good talker but didn’t do as well as I talk. The same thing holds in this case. The current administration talks a good game, but they don’t do shit. When it comes to the war on terror, we don’t have to drum our opinions into our readers’ heads. All we have to do is show what the administration has done, rather than rely on what they’ve said or what has been said about them. Of course, we didn’t editorialize for the 9/11 book either, although we did have to decide what to leave in and what to keep out. This book is pretty much the same kind of project, fact-based but with a strong visual element. To make certain that the faces, buildings and cities look right. So I have been Googling everything, as I had to for the other book.

Were you surprised by the attention that the book has received?

We knew the project was worthwhile, but we had no idea it would create the stir that it has. Over the past year or so, Sid and I have taken part in a lot of interviews. There was one afternoon when I had two camera crews in my house at the same time, one from Japan and the other from Germany. I don’t exactly have a big house! We both appeared on Fox, who were the nicest people, very caring and very professional. Our first TV appearance was The Today Show on NBC. They came with cameras, lights, technicians and a producer. It took them hours to set up — cables everywhere. Then this guy David Gregory flew all the way from Washington and did a very good job. The editing was first-rate. When Gregory started putting on make-up for the interview, I turned to Sid and said, “Who knew?” Sid recently put that phrase on his license plate.

The book seems to be doing quite well. We have received lots of letters — maybe one or two detractors, but a ton of supportive letters. We haven’t had any nuts come out of the woodwork. We've received invitations to speak all over the country, as well as overseas, but I have recently started to turn these invitations down because I wasn’t getting any work done.

The book has been translated into most European languages and is now being translated into Japanese. It’s become an international project. The checks I’ve been getting recently are foreign sales rights. Thank you, Jesus! It’s a 50-50 arrangement with Sid. The success of our book hits a sweet spot for me.

Have you paid attention to the alternative or conspiracy theories about 9/11?

No. I don't pay any attention to various claims about alleged government involvement in the attacks on Washington, DC and New York City. Sometimes I'll come across something on the internet that refers to the Commission’s report as a cover-up or what have you, but I don’t take any of it seriously.

You weren’t paid by the CIA to write this book? [Laughter.] Could you say something about how your collaboration with Sid works on a day-to-day basis?

He sends me a script. Sometimes he calls me, we talk over the script, the layout and so on. It’s all done back and forth by phone and email. When I have finished 10 or 20 pages I send them to him. He looks them over. Sometimes he suggests revisions; something to do with the text, perhaps, or the arrangement of a particular panel. It’s usually easy to fix because I’m working from a computer. And at the same time, I will sometimes offer him comments on his scripts. I might suggest a minor change here or there, just as he might suggest a small change in the illustrations.

Frankly, we are like an old married couple. We finish each other’s sentences. And we never argue. It’s amazing. We get along very well, both artistically and personally. I consider him not only a brilliant writer but a prolific one. His writing is of a very high quality, and he can really crank it out.

SHOP TALK

Can you say something about your work methods in the days before computers?

I was brought up on the very traditional tools of the trade — 2B pencils, No. 2 Sable brushes, art tone or Higgins India ink, and two- or three-ply Bristol boards. That kind of thing. I abandoned the traditional tools many years ago. I now draw with a ballpoint pen — the cheaper the better. I can enhance the line on the computer, using a Wacom tablet. I letter on the computer, color on the computer, and design my pages on it. I don’t use regular-sized pages anymore. I draw on bond paper. I don’t use Bristol board anymore. I scan the drawings into the computer and then design the pages. The scanned drawing is in black-and-white and is more or less complete. I usually create between five and 10 pages of loose drawings before I scan them into the computer.

I really like computer work. I’ve been doing it for more than 20 years. The only thing is that working at a computer can be tiring. I have to sit for 10-12 hours a day. That’s always been difficult, then and now. But that’s the job.

Is there a sport that you are particularly into?

Not really. I like to walk and to work out. I used to do karate. It was fun. I used to play chess, but I stopped. I don’t like blood sports, and chess is definitely a blood sport.

Were you initially resistant to the idea of using computers in your work?

No, I was one of the first to see their potential. When I was working at DC I would write memos to Paul Levitz, telling him that every editor should have a computer on their desks. He kept saying no, and he finally asked me to stop pestering him about it. Two or three years later, of course, every editor was working on a computer.

As it happens, I did a whole Mighty Mouse book on a little Macintosh. I started out on a Mac, then I switched to the Amiga, and then switched to the PC. The Amiga was a great little computer in its day. But the company’s management was awful, so the company never went anywhere. Many of the special effects on Babylon 5 were done on Amiga computers. For a while, I had an Atari, but that was a terrible computer.

Which software do you like to use?

Photoshop always. Sometimes I use Flash so that I can do vector drawings because I don’t like Illustrator at all. Photoshop and Flash are my mainstays. Every now and then I play around with animation programs.

INFLUENCES

Can you say something about your biggest influences? And are there contemporary cartoonists whose work you especially admire?

The main influences on my work are the usual gang of suspects — Milton Caniff, of course, and Noel Sickles, who created the whole film noir look of Terry and the Pirates. Also, Will Eisner, absolutely. The comics master, as I’ve mentioned, was Warren Kramer. As far as fine artists are concerned, the one who goes straight to my heart is Toulouse-Lautrec, who was a great cartoonist. Michelangelo was a good cartoonist, as well. I like Picasso’s sketches and drawings. Not his paintings — they are absolute crap. But his sketches, including the pornographic ones, are very funny and very well done.

As far as contemporary cartoonists are concerned, I have pretty much mentioned Persepolis in every single interview I have done so far. What Marjane Satrapi has done is absolutely sensational. There is a difference between technical ability and the ability to tell a story. What I admire Satrapi for is her storytelling ability. I admire people who can draw you into a story, make you listen, make you read. I also admire Joe Sacco’s work. I thought Epileptic by the French cartoonist David B was a wonderful book dealing with a serious and engaging subject. I thought it was just amazing. The way he illustrates nightmares is particularly impressive. I thought that Maus was one of the most audacious comics I have ever seen. Unfortunately, I thought In The Shadow of No Towers was overblown, overproduced and made no sense at all. The juxtaposition of old comics and new comics eluded me completely.

Strange to say, I never kept up with comics to begin with. Interesting thing to say for someone who's made a living from comics. I occasionally read graphic novels, particularly those that are well-reviewed or that friends recommend, but I rarely read regular comics. I once told a fan of mine that I did not even have a copy of the Amethyst series, and he was kind enough to send me a complete set. Looking over those pages was enjoyable. Yet for me, it is always a question of what is happening now and tomorrow.

Have you left fantasy behind?

Not at all. If a good fantasy project comes along I would be happy to get involved. I like doing lots of different things. After doing Wendy and Richie and Casper for 25 years, I wanted to shake it up for myself. I like to move from style to style. Right now I’m working with Flash animation, and I would like to see a whole book done in Flash. You could put it on the web, publish it and stick it on an iPod.