I'll admit it: eight volumes in, I was worried that Drawn & Quarterly's prestige reprinting of Frank King's early-mid 20th century masterwork Gasoline Alley was losing its steam. While every volume contains more in the way of wit and care and graphic inspiration than just about anything else it shares the comic shop shelves with, more recent installments of the series have lacked both the boldness and the charm of its mid-1920s peak years, and the books' rising price tags (a 20 dollar increase between volumes 1 and 8) suggest a certain lack of continuing commercial fertility. Market fluctuations aside, 2016's seventh volume had me wondering if King and Gasoline Alley didn't at some point fall victim to their own successes. The daily strip's conceit is a bit of simple genius: rather than endlessly recasting characters and tropes in variations on a theme, King's narrative was dynamic, with each installment of Gasoline Alley representing a day in its world's life. Characters grow up, get married, make friends, lose them, and bear along with everyday life's triumphs and tragedies in real time, panel by panel.

The early volumes of D&Q's reprint series showed King discovering and flexing the power of his narrative's structure. Protagonist Walt's gearhead jockeying with his greasemonkey buddies provides fly-in-amber glimpses of daily life in the '20s, his slow-burning courtship of neighbor Phyllis Blossom gives the strip a subtle but powerful tension, and his raising of foundling child Skeezix achieves a warmth and tenderness that the comics form wouldn't even bother attempting for fifty intervening years or so - and one that it's arguably never equaled. King's simple, surehanded graphic mastery and flair for visual experimentation kept pace with his storytelling's growth, and by 1926 or so Gasoline Alley was pretty much as good as anything before or since in comics.

After the peak provided by Walt and Phyllis's wedding, however, the strip hits a half-decade fallow period. King, who had wrung poetry from the camaraderie and yearning of bachelor life and single fatherhood, tried and failed for years to get domesticity to sing the same way. Flat, uninspired sitcom style humor periodically leavened with Little Orphan Annie-lite "intrigue" plotlines make the last few Gasoline Alley volumes a relative drag, with 1932's months-long biography of George Washington as-told-by Walt a grueling nadir. King's attempts to replace his bouncy, well-worn penwork with thicker, woodcut-inflected brush lines during this period misfire similarly. The late-'20s/early '30s books, I hasten to add, are still very good comics! Maybe it was just unreasonable to expect anyone to sustain a peak like King's mid-'20s tear?

But no - this latest volume rights the ship. Skeezix, slowly grown teenaged over the previous volumes' wending course, comes fully formed as the strip's main character, elbowing Walt and Phyllis's constipated kitchen-sink melodrama far to the side. King was always at his sharpest combining the quotidian with a sense of adventure, when his tenderness and care for his characters could give way without warning to the restless energy that his best sequences exude. Too far in either direction and the strip became one flavor of pabulum or the other; in 1933, with Skeezix and his neighborhood gang basically re-creating Gasoline Alley as a whole new comic, King regained his balance.

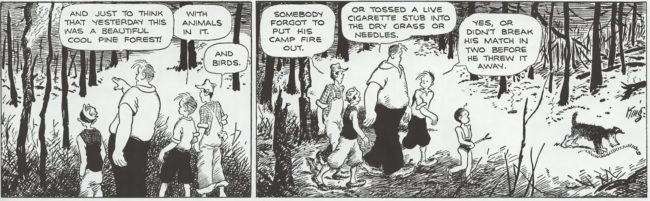

Part of the much-discussed melancholy that pervades early Gasoline Alley comes from its characters' frequently and plainly spoken desire to do big things, to smash the mold of daily life, and their slow accession to the smaller pleasures of routine. Never is this mental tug of war more fevered than in one's teen years, and Skeezix and company's wild vacillation between the boredom of lacking things to do and the all-consuming frenzy of chasing down wild-eyed fancies over this volume's pages provide King with the reddest meat his strip had chomped in years. The kid gang that sometimes goes by the Alley Rangers, sometimes the Four Horsemen, and sometimes the Secret Six take up and discard scheme after scheme with amusement as their only polestar. They share ownership of a broken down car - no wait, a horse, wait, a ram, no, a bike! They bust up, fix up, and dig a secret tunnel to their neighborhood clubhouse. They butt heads with neighborhood bully Clarence, the kind of scary kid for whom the term "juvenile delinquency" would soon be invented, and trail plenty of other shady characters in sporadic ventures as a junior detective agency. They hatch goofy moneymaking schemes with the same varying success with which they invest their infrequent profits. Strip after strip, the energy is palpable and sustained, making this volume of Walt & Skeezix the quickest and most compulsive read of any so far.

Skeezix's idylls aren't presented as adventures, really - they're told like anecdotes, with wry comments from characters young and old punctuating the rising action with wit and giving them the grain of fondly recalled memories. The reader watches more than experiencing, the better to mine pleasure from the kids' travails. If you ever wished for a comic book version of Tom Sawyer or Caddie Woodlawn that equaled the power of the original articles, here it is, by a master of the form in just as much control of what he's doing as Twain or Brink were. King lays down a template in this volume that's powered as big a number of good comics in the years since as anything that doesn't wear a cape - from Lulu and Archie to Calvin and Raina, kid-gang comics receive a playbook here as a great cartoonist finds a way to raise his level after having already done so more than once in his career. Where it took Comics the form half a century and change to latch onto the incremental slice-of-life storytelling King was doing in the '20s as a model worth emulating, this stuff - perhaps less sophisticated and "serious" to modern eyes - made an impact right away, and the style hasn't been off the stands since.

King's drawing works back into top form over this volume as well. His travails with the brush show their worth here once he's returned to his familiar thin, wafting pen line. Where King's best '20s pen inking is graphic to the core, a perfectly balanced combination of line and shape, black and white and patterning, his drawing here pulls off the somewhat miraculous feat of being rendered without feeling so at all. King's characters retain all their bounce and simple expressiveness, but light sources and gravity feel more in evidence without making themselves a center of attention. Little scribbles on a blank space here or the ebbing of black space into heavy hatching there do an amount of work out of all proportion to the space they take up on the page, making the action feel more grounded in a real setting than it has in years. King's instinctive way with designing characters gets a workout in this volume as well, as Skeezix's cronies are introduced and eased into individual sets of gestural cartooning tricks. The springy, grasshopper-like jackknifing of the body language King gives his teenage cast is miles from the slouched rolling of his longtime Alley regulars, but by the book's end the kids' bodies feel as inhabited as any of their author's longer-tenured silhouettes do.

Speaking of silhouettes, Gasoline Alley's longtime aspect ratio abruptly changes in this volume, with one page of the short, wide (mainly) four-panel strips King had spent a decade and a half doing leafing over into a page of taller, narrower tiers better suited to three. It doesn't jar the work from the steaming pace it's built up over the book's preceding few hundred pages, but it has a quickening effect on the strip's internal rhythms, and it pushes the framing of King's individual drawings, which for a year or two had been zooming out to about as wide as he ever got, to the baseline of a knees-up two shot. This change in formal structure goes unexplained in Jeet Heer and Chris Ware's reliably (sometimes comically) exhaustive supplemental writings, but to my mind at least it has a livening effect, holding readers that extra bit closer to the vigor of Skeezix and crew's flails. In a book that sees King building up a head of storytelling steam, this shift provides a final stomp of the gas pedal.

Also unmentioned by Heer and Ware (perhaps out of consideration for the King estate, which has provided D&Q's reprint project with a wealth of family artifacts), is a Walt-and-Phyllis storyline that, though relegated to a subplot by Skeezix's adventures, is the most interesting one in years. Walt, Skeezix, and the gang go camping for a long summer, leaving Phyllis to visit a seaside resort where she undergoes significant weight gain. For years the rotund Walt has been fighting the battle of the bulge, and now his wife joins him, to his slightly sadistic amusement. This isn't outside the sitcom-y wheelhouse that King had boarded the two characters in for years, but the emotional tenor of these strips feels rawer, closer to the surface, than previous storylines. Family photos of the Kings, always prevalent in D&Q's reprints, may or may not provide a clue: the wiry, energetic King and his matronly, prematurely aged wife Delia present a frankly startling contrast. Heer's introduction to this volume focuses on King's molding Skeezix's subplots from his own son's adolescent scrapes, and one can't help but wonder if any of the book's other narrative threads originated as close to home.

It's tough to boil a volume containing more than 700 comic strips by an all-time great at the top of his game down into a few paragraphs; I fear I'm wearing out my welcome here as is. So I'll conclude by stating that this volume of Walt & Skeezix is the best in years, and as fine a piece of work as any in the series. A publishing venture as venerable as what D& Q is doing with King's work inevitably doesn't invite the same level of excitement as brand new books by rising talents, which might be why new volumes have become less heralded over the past decade. But this is still one of comics' all-time publishing endeavors, one that fully earns its stewardship of one of our all-time greatest works. I'm loath to tell anyone to vote with their dollars, but the sheer wealth of what the eight volumes of Walt & Skeezix present pushes them beyond mere comics history and into the realm of cultural patrimony, however minor. Buy them because it's important that more be made; buy them because no matter how long and hard you look, you won't find anything better.