Walking is one of those crucial things that many of us pay little attention to. Lizzy Stewart has drawn inspiration from this typical activity for her recent comic Walking Distance. A rumination on transitional moments, this book is about the sort of thinking walking encourages, and a demonstration of how comics are well placed to remediate that experience. Journeying is a theme which seems to have preoccupied Stewart, and a brief look over her online portfolio shows various pieces which represent motion. One magazine cover is a train track that traverses a city, a couple more examples show people moving through water. Also on display is her penchant for bold, wavy patterns, the type which reveal themselves towards the end of Walking Distance as abstractions of situationist dérives and more purposeful walks.

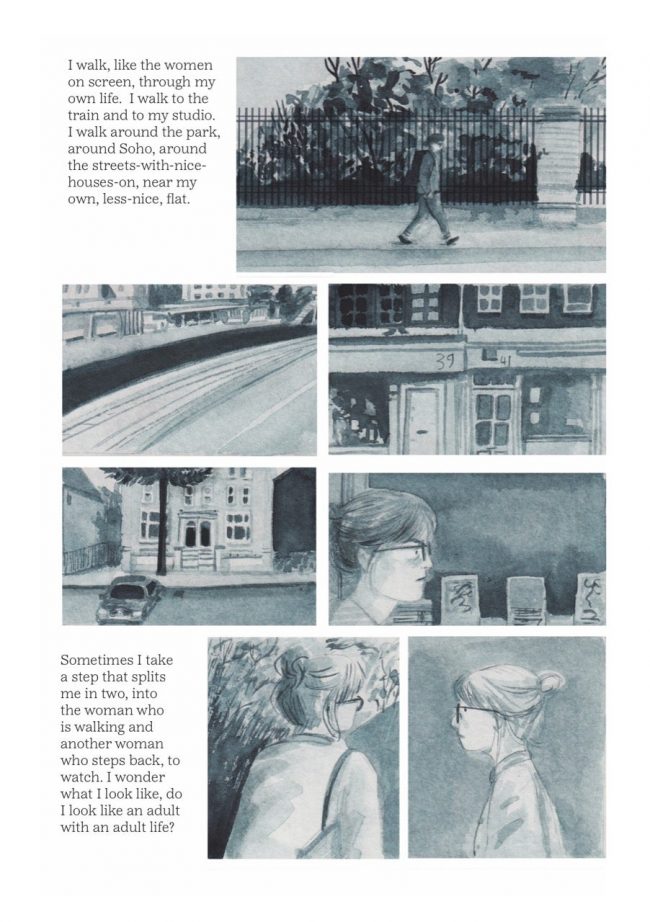

Walking Distance opens with freeze frames of Meryl Streep, Amy Irving, Michelle Pfeiffer and Diane Keaton walking in various movies. Stewart says later that in these moments “they are simply people, immersing themselves in the city.” Through this collage of movie walks we find that the act of walking suggests agency and self sufficiency. This collage is also reminiscent of the way that brief glimpses of expressions of passers by can capture the imagination. On other pages, cropped snapshots of ordinary sights - the corner of a roof, some branches - are brought together as a memory bank of everyday objects. Walking Distance draws on the role of association in comics to depict walking’s associative aspect. In both cases, the comics page becomes a metaphor for how we collect snatches of experience as we amble through life and make unexpected connections between unexceptional moments.

Almost always in a blue hue, many of the panels and figures in Walking Distance are painted in Stewart’s trusty watercolors. The result is an ambience which is at once melancholic but also soft and fluid. A more cartoonish, pen-based style is employed elsewhere, when characters are detached from environments and personalities become more important. The juxtaposition between these styles suggests distinct moods between the experiences and memories on display. The playful simplicity of the people-centered segments contrasts against the more ambiguous, in situ ruminations.

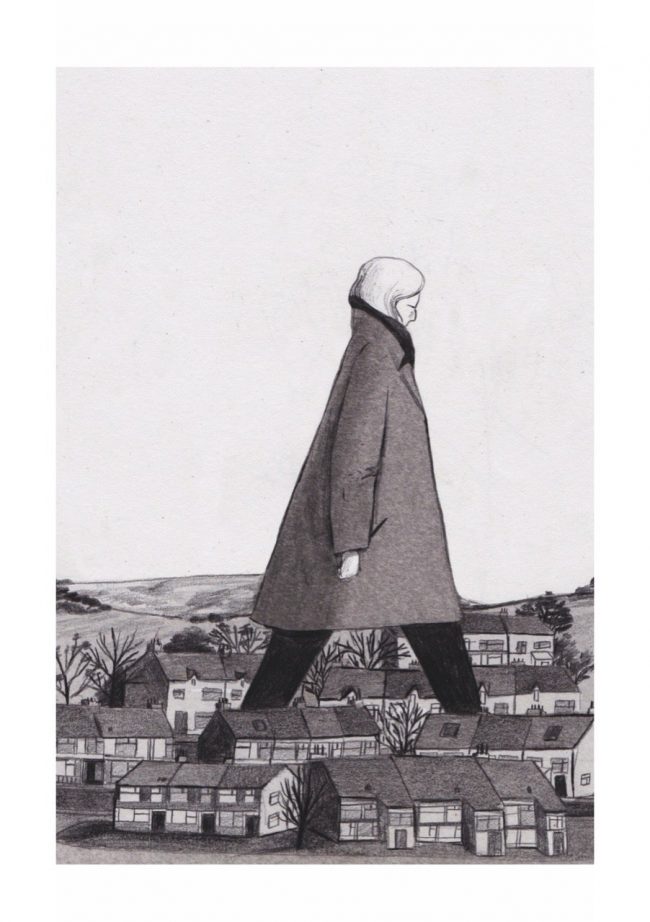

Stewart’s cartoon avatar says that “walking in London is when I feel most certain.” This is the basis for her travels by foot through the British capital. London isn’t the most obvious location for a calming stroll: you’re never far away from traffic noise, the smell of frying food or a bustle of determined pedestrians. Walking in London could also be seen as a subversive act, one which reduces a city so sprawling and oriented around busses and cars and “the tube” down to a human scale. While a writer like Iain Sinclair has utilized walking in this city as a way to track and critique national politics at a local level, Stewart employs walking as a meditative practice for self-reflection. In both cases, walking is a method through which an immediate environment becomes a locale. And as a landscape becomes recognizable, a faceless or lost individual becomes like Streep, Irving, Pfeiffer, Keaton or Stewart: a protagonist in their own story.

Stewart’s cartoon avatar says that “walking in London is when I feel most certain.” This is the basis for her travels by foot through the British capital. London isn’t the most obvious location for a calming stroll: you’re never far away from traffic noise, the smell of frying food or a bustle of determined pedestrians. Walking in London could also be seen as a subversive act, one which reduces a city so sprawling and oriented around busses and cars and “the tube” down to a human scale. While a writer like Iain Sinclair has utilized walking in this city as a way to track and critique national politics at a local level, Stewart employs walking as a meditative practice for self-reflection. In both cases, walking is a method through which an immediate environment becomes a locale. And as a landscape becomes recognizable, a faceless or lost individual becomes like Streep, Irving, Pfeiffer, Keaton or Stewart: a protagonist in their own story.

In her book Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit traces Western discourses around walking, embracing protests and public spaces as she meanders through the activity’s discursive history. She writes that: “Moving on foot seems to make it easier to move in time; the mind wanders from plans to recollections to observations.” This is exactly the associative method which Stewart employs comics to display. “The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking,” Solnit continues, “and the passage through a landscape echoes or stimulates the passage through a series of thoughts.” In Walking Distance , Stewart’s internal landscape is formed of a “childish view of pregnancy,” thoughts about outgrowing her hometown, Britain’s political situation, and how to best participate in life. This landscape is the passage through which the reader becomes Stewart’s fellow peripatetic.

But why take where you are as a way to work out who you are? Stewart provides one suggestive answer when she states that “It’s no use drawing my own face over and over and hoping to find some truth in it.” Walking Distance suggests that the individual is, or at least feels, constituted by their experience of the everyday and of their immediate environment. Walking in a locale which you recognize is a way to recognize yourself. The truth about yourself is out there, quite literally: it surrounds you. This is perhaps why for many people true nomadism would be such a difficult prospect. For a society built on home ownership and regional identities, nomadism can create a state of being permanently lost, out of place. This is also why homelessness is such a worrying proposition; no only because it threatens a loss of crucial material possessions, but also because it suggests a future in which one lacks a relationship between oneself and wherever you are. The “-less” suffix presumes that the person without a home is not quite whole.

In where she walks, Stewart finds comfort. Eventually, the swirling lines of thought and traces of paths trodden through London converge into an indistinct abstraction. This reflects the way in which an experience of life becomes a compilation of tightly intertwined but still distinct layers of memories and feelings and thoughts. The where and the who are recognized as codependent. Through focusing on her manoeuvres-by-foot through the city, Stewart unravels and (re-)weaves the ways in which walking is a tool for understanding the self, and how comics can be used to understand walking. Walking Distance depicts the contours of an internal landscape, and the comics page becomes the space through which we can journey with an introspective protagonist.

In where she walks, Stewart finds comfort. Eventually, the swirling lines of thought and traces of paths trodden through London converge into an indistinct abstraction. This reflects the way in which an experience of life becomes a compilation of tightly intertwined but still distinct layers of memories and feelings and thoughts. The where and the who are recognized as codependent. Through focusing on her manoeuvres-by-foot through the city, Stewart unravels and (re-)weaves the ways in which walking is a tool for understanding the self, and how comics can be used to understand walking. Walking Distance depicts the contours of an internal landscape, and the comics page becomes the space through which we can journey with an introspective protagonist.