It’s wrong to limit our understanding (and appreciation) of a story in relation only to the modern socio-political context by which we read it. For example, it’s tempting to rate Jason Lutes’ Berlin highly because the series was completed when the particular zeitgeist was to talk about fall of old global empires and the rise of modern fascism. But to do so would ignore all the other good stuff – the way he writes characters, the way he pencils the city (even as it crumbles) in such a loving manner, the way he makes all the small moments stand up both in their own and as a part of such a large tapestry. It's not to say that comic books aren’t political, only that this shouldn’t be all that they are. That’s a reductionist view.

There has be something of the sublime about the work to make it survive: Berlin would still be great even if [political figure you hate] ended up lost and banished to the sun and everybody [moved to support your obviously-correct ideology]. Its greatness is informed by our times, but is not limited to them. That being said? The Eternaut sure feels like the single most relevant work of fiction one can find right now. You don’t even need to crack the book (or pull it out of the fancy slipcase) to feel it, just look at the face of our protagonist, behind that improvised mask that make him appear like a diver (the sea is a recurring motif), and understand – this book is zeitgeist!

The Eternaut begins with a testimony, and for all that the book evokes Robinson Crusoe in its narration (writer Héctor Germán Oesterheld was quite the fan) I couldn’t help but think about Moby Dick. Robinson Crusoe is a hero in the classical sense, a man who builds up his world through rugged individualism (and the grace of god). Our Eternaut, a time traveler who materializes one night in Argentina with a warning of the coming future, is to my mind more like Ishmael – he is not the hero of his own story, but a witness to dozens of other stories. His importance is not at what he does, but at what he records – the acts and ideas of many as they struggle against the impossible disaster.

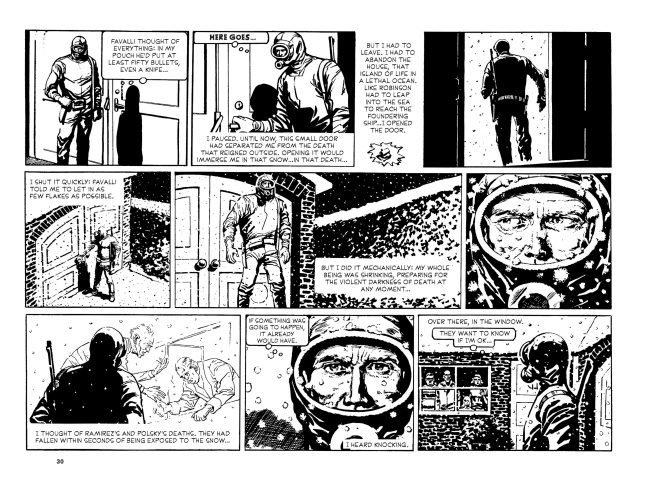

This is the story of Juan Salvo, his friends and family, one fateful day when snow begins to fall in Buenos Aires. A rare enough event, made even rarer by the a strange fact of that snow – it’s deadly. Anything it touches dies on the spot. Rushing to seal all door and windows, the small group is trapped together, locked in a house that has become a fortress under siege. The outside world, once so familiar and comforting, is now something alien – uncanny (in the Freudian meaning).

Leaving the house, to get groceries or medicine, has become a life-threatening adventure – an epic quest rife with danger. It requires the protagonist to wear a full-body suit and face mask that make people appear like deep-sea divers (again – notice the sea motif). It has become more than the most famous element of the series, it’s a full-blown icon; found in graffiti on the walls of major cities, reclaimed from the work as an-purpose symbol – alienation, survival, oppression…. a man surrounded by death.

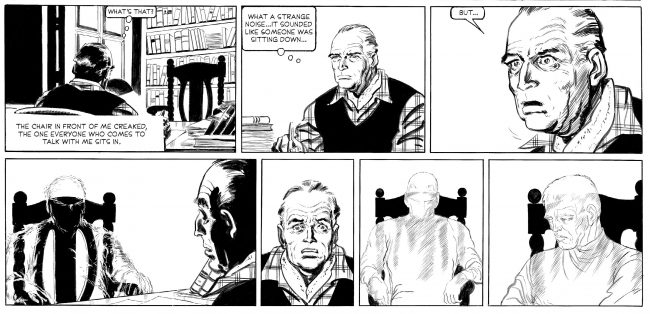

Post-apocalyptic fiction is dime a dozen, and plague-narratives are an old and well-established genre; but there’s something about the suit and mask, the improvised design by people thinking on the fly, that rings true now – nobody in charge seems to actually know anything, and so people have to make their own solutions. These early parts of the story are undoubtedly the best; in terms of sheer tension and building up the mystery, Francisco Solano López’s are is as straightforward as they come. Stark and simple black and white; faces and bodies slightly dramatized, eyes and mouth opened in wide shock, but still answering the call of realism. His greatest strength is his control of geography and architecture: for the world to appear threatening he must first conceptualize it in its normality. There’s no ‘artificiality’ to the horror of The Eternaut, no exaggerated angles or unreal colors to influence your perception – the fear is the result of the place in the characters in the world. nothing more or less.

Once we move past this phase, when the story reveals the beings responsible for the deadly snow, the story becomes slightly more generic. It’s an alien invasion story, with our heroes joining forces with the military while facing a series of escalating threats. Some of that stuff definitely appears on the wrong side of being old-fashioned (flying saucers brought down by cannon fire, aliens that are variations on earth life forms) – the march of time is cruller to science fiction more than most genres.

Yet even there, even as we step away from out zeitgeist and into realms of purer fantasy there are parts that keep The Eternaut working decades later. Where our typical post-apocalyptic tale focuses on individuals, or tiny groups, rising up from the ashes of failed society, one that could not buckle the pressure of sudden change, The Eternaut shows people joining forces and working together. Not always successfully, and not without suspicions and inner struggle, but they try. I can see that character of Favalli, the calculating scientist whose choices are always based on cold pragmatism, taking the lead in a story like The Walking Dead; making the ‘tough decisions’ that keep the other protagonists alive by keeping them alone. Here, Favalli is allowed to make mistakes, and it is the simple worker Franco, happy and outgoing, that gets the most traditionally heroic moments.

Oesterheld claimed that the point of The Eternaut is that there is no single protagonist; the ‘hero’ is the group. This positions the story as specifically political, opposing the ‘rugged individualism’ of American culture. Indeed, the story evokes Cold War fears not only with its allusions to nuclear annihilation (though, again, the story’s understanding of nuclear power is somewhat limited – our heroes escape a nuclear attack by riding a bicycle) but with its conception of the invaders. We never see THEM, only other species they enslaved to their bidding; like global empires using client-states and founding revolutionary groups to do their dirty deeds.

Oesterheld’s later work would be even more obvious in its political bent, including a remake of The Eternaut (with legendary artist Alberto Breccia, to be released in English as Eternaut 1969) and a biography of Che Guevara, as well as in his real life. Oesterheld joined the guerrilla group Montoneros and ended as one of many los desaparecidos in Argentina; his date of death just an educated guess. He didn’t just talk the talk.

I don’t want you to think all of these things make The Eternaut into some perfect and untouchable work; for all of its virtues and high-ended aims the book suffers as a product of its time and method of production. The Eternaut can imagine our modern capitalist reality being demolished by a grand disaster, but it can’t quite imagine the same for gender roles; Salvo’s wife and daughter disappear for almost a third of the plot, and when they re-enter story they fail to effect it in any way. They are something for Salvo to pine for, the home and routine that he lost. In a story that tries to make everyone a character and not a statistic the lack of care for women characters is telling.

One also cannot forget the original serialized nature of the comics, published weekly over a year. The Eternaut is not ‘repetitive,’ there’s a solid forward momentum to the plotting which keeps the reader hooked, and López’s keeps at pace with the story - even when it calls for dozens of characters to engage in larger and larger battles. For all its political aspirations this also a populist work of entertainment (and I mean it in the nicest way possible – being accessible doesn’t make it in any way less artistically valid); but it does often rely on simple shocked ‘gotcha moments’ to end a chapter. One cannot count the number of shocked faces shouting variations of ‘it cannot be’ throughout the narrative.

As for the ending – I am genuinely unsure what to think of it. I hate it one moment, and like it the other. It’s rather inevitable considering the testimonial nature of the story, The Eternaut tells us the story, so he must have survived and found a way to travel through time, but it feels a bit too right – like a writer’s workshop solution. The story always teeters on the edge of death, one last-minute escape after another, and suddenly its over in a flash, as if the creators got tired of the story and sprinted to the final to make their point.

Still… The Eternaut hold; and it’s not because our reality suddenly appear to reflect it a bit more. I read it the first time before the current crisis and was struck by its power, and I am a mere follower in the footsteps of untold numbers before me. It might strike us as more relevant now, but that would be mistake. It was made in and for certain circumstances, but it transcends these them – it’s still being read and discussed and analyzed when these particular circumstances gave way. Like other great works art its context is human existence – it’s always relevant.