If there's a villain to be found in Leela Corman's return to comics, Unterzakhn, it's hypocrisy. While this story of twin Jewish girls growing up in New York's Lower East Side in the early 20th century is also about the art of survival and the arbitrary nature of what determines who lives and who dies, it's really a celebration of human kindness in the face of the abyss and a condemnation of arbitrary, rules-based ethics systems. Corman jumps forward and back in time to tell the story of Esther and Fanya Feinberg, their father Isaac, and their mother Minna. There's a brutal, bracing lack of sentimentality in how Corman tells the story of how they get along in a New York that may be an ethnic melting pot but is sharply divided along ethnic and class lines. At the same time, this is no celebration of the old country or tradition either. The Russia that Isaac flees is a savage, unforgiving place for a Jewish person. And as unpleasant and unfair as America is, there are still ways for a person to advance if they are willing to pay the price. What that price might be, and how steep a toll it might take, is at the center of the fates of each of the characters in the book. Unterzakhn is also a celebration of women as survivors, as doers, as fallible beings who have to engage with an extra set of obstacles that men never even have to consider.

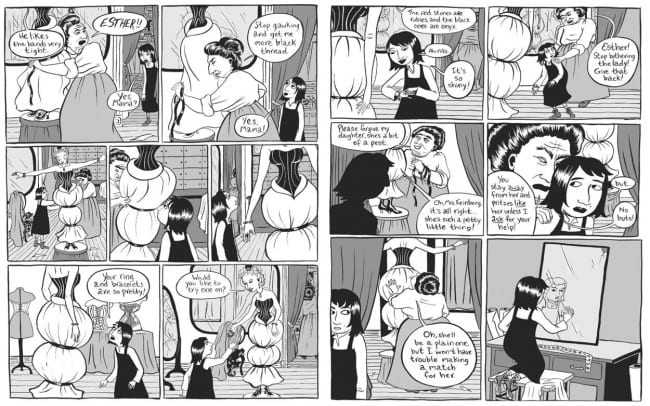

As the book opens in 1909, the girls are six and only just beginning to learn about the world surrounding them. Their parents are the typical infallible figures a child of that age perceives: their father is warm and kind, full of rich stories, while their mother is hard and cruel, yet demands respect. Her insistence on bringing the girls up in a non-goyish way seems almost romantic at first as she tries to keep ethnic traditions alive, but as the girls get older it becomes obvious that her virtue and motives are greatly in doubt. The book opens with Fanya observing a woman bleed out after attempting to give herself an abortion, leading her to meet the "lady-doctor" Bronia. She's an OB/GYN who also secretly performs abortions on the side. Meanwhile, Esther drops off a package of clothing for a customer of her mother's fabric store, only to be introduced to a burlesque house and brothel. Those two events shape their lives in frequently distressing and unexpected ways, as Corman relentlessly subverts expectations throughout the narrative.

Corman's attention to period detail and the quirks of Yiddish bring this book to vivid life. She captures the clangor of a typical busy street (especially in how a child perceives it), the claustrophobic nature of city living, and the mix of excitement and danger potentially lurking around every corner. Her figures bear a stylish simplicity, but Corman also excels at drawing ugly and grotesque figures as well. Her style is realistic but slightly rubbery, allowing for expressionist flourishes. She draws the hair of certain characters not so much with ink as with smeared scribbles, so as to represent a tangled bird's nest quality. She doesn't draw sexy characters but rather characters who are frankly sexual. Ever since her first book, Queen's Day, Corman's pages have always emphasized spotting blacks, and the most attractive pages in this book continue that tendency. Like the New York she draws and the characters she develops, her art is both beautiful and ugly.

As the story unfolds, Fanya learns how to read (in defiance of her mother) and works for Bronia, while Esther deceives her mother by getting a job at the burlesque theater doing odd jobs. Fanya remains the "good daughter" even if she doesn't bring in any money, while Esther is eventually shunned by her mother for becoming a dancer and later a prostitute. Their father dies a broken man even as we learn that Minna not only slept with every man and boy on the block, but that she had been doing such things her whole life. Corman has a complex take on this character, condemning her not so much for expressing her sexuality but for the way she treats her husband and hypocritically shuns her daughter for supposedly "shaming" the family, heartlessly excluding her when the youngest daughter in the family dies. Indeed, Minna's whole marriage is a sham, as an extended flashback to Russia reveals. We see Isaac dodging Russian killers and meeting a woman he falls in love with before he's offered safe passage to America if and only if he marries Minna, who is shaming her family by being promiscuous.

In this indifferently hostile world, some would say that there's no such thing as good or evil--just life or death. However one is able to survive, Corman asserts that one still has the choice to be cruel or kind. Isaac certainly does not deserve the fate he receives, but Corman implies that he is better off living on his wits in Europe than living a lie in America; it's undeniably true that the marriage to Minna may have saved his life in the short term, but it led to other sacrifices in the long term. Fanya defies her mentor by disseminating information, handing out condoms and generally saving the lives of women Bronia does not approve of, but her own inability to balance her feelings against her sex drive winds up being her downfall. Even as she accuses Bronia of being a hypocrite for the selective nature of whom she deigns to treat, Fanya's own hypocrisy has tragic circumstances.

At the same time, Esther survives and later thrives by not denying who she is. In a world where life and death at the hands of brutal johns requires a razor-sharp understanding of self, she was forced to either evolve or die. Her ability to negotiate the hatred of the fellow women in the brothel and defend herself when needed put her in a position to accept the charity of another character who is true to himself. Meyer Birnbaum is a punk kid that Isaac manages to save from a number of scrapes in Russia; as a kid, he just didn't know when to shut up, even when his life was in danger. We meet him in a flashback, but he reappears later to watch Esther perform and then later becomes a john. There's a certain randomness to why Birnbaum makes it and Isaac doesn't, but Birnbaum's frank honesty is what allows him to thrive in New York City.

Even as Esther manages to get a wealthy New York businessman as a benefactor and lives in a posh penthouse, it's obvious that she doesn't forget her roots. She uses her wealth and influence to both achieve her dreams of becoming an actress but also helps out the madame who gave her her start as well as her sister. "You're not the only do-gooder in New York," Esther tells Fanya when they're reunited. It's a sign that however hardened she has to become in order to survive, the city is unable to claim her essential humanity, a humanity that was created and nurtured in the relationship she had with her sister as a young girl as well as the kindness their father always showed them. While Corman allows for a lot of moral ambiguity in the conventional sense, there seems to be no question which characters are the most humane. The complex route she takes to guide the reader to arrive at these conclusions, the level of detail she includes, and the feelings that the journey evinces are what make this a successful work.