Every story carries with it stories that aren’t told—versions of itself that might have unfolded had the author chosen slightly different paths for his or her characters. By making a decision to tell a tale in a particular way, all other version are eliminated. But what if instead the reader were able to recognize other ways a story could be told, other ways the action could proceed? And what does a story look like when this potentiality becomes fact?

To start, it might look something like Kevin Huizenga’s Fight or Run, a series of stories in which two characters fight each other or one runs away. Each setup draws from a fixed set of relations, and in each telling (A fights B and wins; B runs from A but then kicks A’s ass; A fights B and loses), all of the variables are present, since the very nature of the exercise is that it is a diagram of possibilities. Spun with more detail, and you might have something like Rashomon or As I Lay Dying, in which multiple perceptions of the same event gradually produce a fuller picture of the characters, their complexities and subtle differences.

This kind of diagrammatic structure, rich with potential, characterizes much of Huizenga’s comics. Variables are at the heart of his work. The "or" in Fight or Run and the title of his minicomics series Or Else highlight the fundamental play of alternatives. Gloriana, a collection of previously published stories, is filled with tales that begin only to reset and begin again. In two panels, the Wendy Caramel prologue builds a symphony of office activity—charted temporally on a graph, in the culminating panel—only to have Huizenga draw from it a single sound to continue the narrative. It resembles a short piece of thread with a big tangle in the middle.

On their own, diagrams don’t formulate or correlate to emotions, but even the most minimal plot can hint at something deeper. The Fight or Run comics are absent all characterization, detail, and narrative flourishes, yet the instant in which a choice is made creates a moment of tension. The second story in Gloriana, “The Groceries”, uses a banal task—unloading groceries—to spin out Glenn Ganges’s daydream about what might transpire in the near future, before retracting the narrative to the “present,” then sending out a new shoot that depicts Wendy’s daydream. Their two imagined scenarios aren’t fantastical but grounded in the commonplace: the often anxious job of raising a child.

On their own, diagrams don’t formulate or correlate to emotions, but even the most minimal plot can hint at something deeper. The Fight or Run comics are absent all characterization, detail, and narrative flourishes, yet the instant in which a choice is made creates a moment of tension. The second story in Gloriana, “The Groceries”, uses a banal task—unloading groceries—to spin out Glenn Ganges’s daydream about what might transpire in the near future, before retracting the narrative to the “present,” then sending out a new shoot that depicts Wendy’s daydream. Their two imagined scenarios aren’t fantastical but grounded in the commonplace: the often anxious job of raising a child.

While not included in Gloriana, Huizenga’s adaptation of an entry from Kafka’s diary (from Or Else #3) works with a similarly spare framework but achieves far more in emotional effect. (It’s easy to see why this entry intrigued Huizenga—its action can be diagrammed quite simply.) As Kafka steps out to take a walk, he observes, from a corner on an empty street, an “insignificant municipal employee” in the distance inexplicably hosing down the pavement, a task he deems inappropriate; at the next intersection, he watches two men fight, pause, and fight again. In a story in which almost nothing happens, narrative tension is created by Kafka’s very nonparticipation: he seems on the verge of throwing himself into the fray, but in the end, he merely issues a tremulous call, heard by no one, to stop.

When Art Spiegelman, in conversation with Huizenga, suggested that the younger cartoonist’s “distillation process” mirrors poetic concerns, it’s telling that Huizenga countered with “maybe the analogy would be a designer.” The distinction is apt: though Huizenga’s comics work stylistically on the level of poetry, he organizes them according to design, or architectural, principles. His visual stories—often wordless or with a minimum of dialogue—must be read structurally. It’s not for nothing that he’s cited the influence of Chris Ware’s distinction between reading and looking at comics. For Huizenga, who admits a disinterest in visual art (and, by extension, the pure aesthetics of drawing), the idea of reading an image is akin to, say, interpreting the system of a flowchart.

When Art Spiegelman, in conversation with Huizenga, suggested that the younger cartoonist’s “distillation process” mirrors poetic concerns, it’s telling that Huizenga countered with “maybe the analogy would be a designer.” The distinction is apt: though Huizenga’s comics work stylistically on the level of poetry, he organizes them according to design, or architectural, principles. His visual stories—often wordless or with a minimum of dialogue—must be read structurally. It’s not for nothing that he’s cited the influence of Chris Ware’s distinction between reading and looking at comics. For Huizenga, who admits a disinterest in visual art (and, by extension, the pure aesthetics of drawing), the idea of reading an image is akin to, say, interpreting the system of a flowchart.

Huizenga’s “The Sunset”, in which Glenn observes a sunset from a library window, is a small masterpiece. Glenn’s emotions in viewing the sunset are the story’s sole subject, and Huizenga portrays them through formal means. Glenn begins to relate the experience, stops, begins again from a slightly different vantage, then stops and tries again. Such is the bulk of the story. “The Sunset” is especially inventive because Glenn’s desire to describe his overwhelming emotion comes through his inability to do the task in a straightforward way. Instead, there are narrative gaps, stopping and starting, and alternating perspectives. Huizenga deconstructs the moment, so that it appears either as a stuttering failure to relay the experience or as an experiential knot Glenn cannot quite parse.

The explosions of awe that Huizenga describes through a compounding abstracted chaos—anthropomorphic sounds busting through panel borders, rhythmic arrangements of tiny panels, regular line work that loosens into scribbled marks—help to emphasize how spare his narratives typically are. Huizenga is a taker-outer, to use Thomas Wolfe’s distinction; he’s a minimalist writer, distilling complex interior experiences into simple yet foundational moments. Ware is also a taker-outer. Another is Charles Schulz. Glenn Ganges is Huizenga’s everyman, as Charlie Brown was Schulz’s. The way Schulz routinely places Charlie Brown before the football, only to pluck it ruthlessly from his reach, is, as Huizenga himself has pointed out, a way of circling around the same idea without ever arriving at the same conclusion—or, for that matter, without ever really telling the same story twice. It’s repetition without being repetitive; each attempt is a variation on a theme. “The Sunset” epitomizes this idea.

In “The Moon Rose”, the enthusiasm, spurred on by nervousness, with which Glenn describes to his neighbors the science behind the unusual moonrise is akin to Charlie Brown’s anxious existentialist speeches (often soliloquies) that always end in a flat note of ironic defeat. Glenn spends a dozen pages, dense with diagrammatic scientific explanations, in a fit of social awkwardness, only to conclude abruptly: “So don’t worry, okay? Just a regular old moonrise”—complete with bead of sweat dangling from his temple.

In “The Moon Rose”, the enthusiasm, spurred on by nervousness, with which Glenn describes to his neighbors the science behind the unusual moonrise is akin to Charlie Brown’s anxious existentialist speeches (often soliloquies) that always end in a flat note of ironic defeat. Glenn spends a dozen pages, dense with diagrammatic scientific explanations, in a fit of social awkwardness, only to conclude abruptly: “So don’t worry, okay? Just a regular old moonrise”—complete with bead of sweat dangling from his temple.

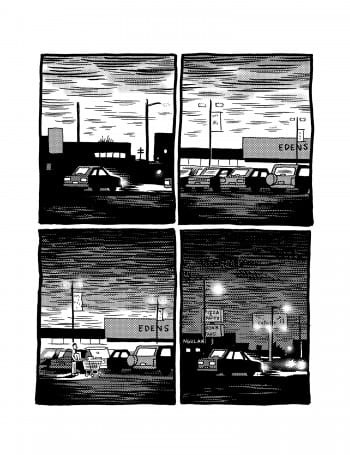

In Gloriana’s last story, “Basketball”, which serves nicely as a kind of epilogue, Huizenga reminisces on a high school career playing the titular sport. But retrospection blurs the past. He admits that what he most remembers is a view out a fogged-up bus window: “all the lights fuzzy with halos mov[ing] across the steamed up glass.” The past, already completed, contains no potentialities, no variations. It is only a smudge of single events. The future, though, has motion, and anything is possible.