Is Shira Spector’s Red Rock Baby Candy the kind of formally nutso creation that people only make for their first book? Like a debut record album, it's a chance to throw out every trick you’ve been saving up for years because your audience doesn’t know what to expect from you yet. It's a neverending botanical garden that reveals new colors and scents around every corner, this book blossoms all over the place with experimentation, pages full with collage and painting, ink wash and pencil.

What's most interesting is the way Spector weaves her words around the page, making your eyes and brain work hard to follow the threads. You can feel your eyes moving left and right and up and down and in circles, grabbing a piece from here and a piece from there and assembling meaning. Here's one early example, on the second page of the book, when Spector writes, of her father, "I miss him and I want him returned," only "returned" is crossed out and "back" is written above it as a substitute. She breaks these words across two lines, though, and although "back" is supposed to go on the second line, it ends up on the first one, so the first time you read it, it seems to say, "I miss him and back I want him," and you don't realize how it's supposed to read until you hit the last, struck-through word, at which point your eyes record-scratch back to the beginning of the text box. There's an actual record player in the image below, as if to unearth that feeling. This constant revision, dragging the reader along for the ride, feels like being dipped into someone else's thought process, and it's crucial to Spector's project, in which she does something similar with her life: reexamining it like a knitter scanning for a flaw, then picking up the missing stitches and inserting fixes. It's not very linear but neither are humans. Time is real, but stories are things we make, and memories are stories we use to tell us about ourselves.

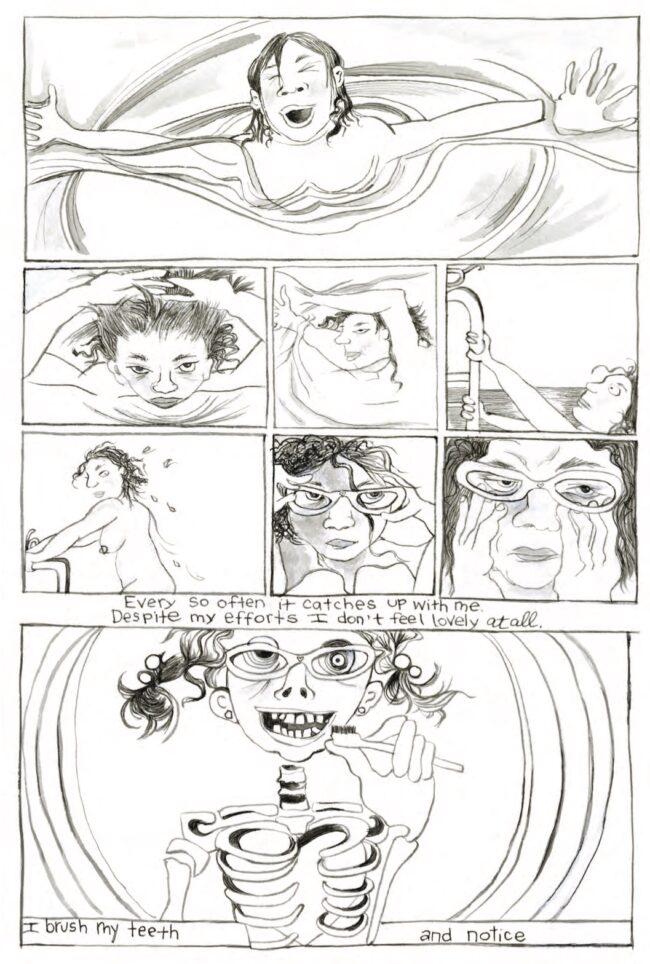

The book starts out in black and white, in panels that are more traditional but already seeping into one another. A flower overlaps two panels. A leaf inserts itself between two words of narration. Things are already a little messy. Pink enters around page 12, with flowers and dresses and lipstick, arteries and capillaries and uterine linings. Spector slowly adds in other colors, one at a time. Her lines get more varied, with black ink wash. Her lettering not only scoots around the page like a living thing but changes how it presents itself: cursive, printing, spangled letters a la Vegas, all caps, all lowercase, cross stitched, multicolored, and more. How is it readable? Sometimes it's not. Spector's truest predecessor isn't a comics artist at all but the poet Walt Whitman. Her book is a song of herself, even down to its titular parody of "Big Rock Candy Mountain." "Poetic" can be an insult, but it's not here. Spector's book, which is mostly about infertility and the deaths of her family members, would be much harder to read emotionally if she were more direct and less poetic about her pain.

Spector reminds me of Aline Kominsky Crumb in the way that she's unafraid to reveal her vanity, one of the hardest weaknesses to expose, but she's both gentler and more probing, less of a goof. She is unapologetically feminine. She likes face creams and pretty pink dresses and things that smell like sugar, things she's not supposed to like as a lesbian feminist. The world shames women both for caring about their looks and for not caring about their looks, and so there's no way to escape all that weight. It sees us primarily as tools to reproduce the species, and so Spector's infertility is a painful failing, amplified by the fact that another perspective would tell her not to feel that way. She has a child, but she wants very much to give birth to another, and she threads throughout the book all the times she tried and failed to get pregnant in chains of typewritten text. Mythology and superstition and science get equal time, and that’s how it feels when you’re trying to have a baby and it keeps on not working out. “Urge and urge and urge, / Always the procreant urge of the world. / Out of the dimness opposite equals advance, always substance and increase, always sex, / Always a knit of identity, always distinction, always a breed of life,” writes Whitman, and it’s true here, too.

Is this book a little bit of a mess? Objectively, yes. I’m not sure that Spector’s accounts cohere into the kind of perfect formal narrative that Fun Home trained us to expect. But I’m not sure that that’s a failing either. The book is about containing multitudes, a kind of barbaric yawp in celebration of love and family (built and inherited), sugar and spice, rock and candy, and it’s a beauty.