Though this is the ninth book in Michael Rabagliati’s semi-autobiographical series, it’s my first encounter with the work of this highly respected, multiple award-winning Quebecois cartoonist. Honestly, I had no idea what I’ve been missing.

An exploration of adjusting to life in late-middle age, Paul at Home is a masterclass in comics storytelling, rich in humor and pathos, and capturing the sheer breadth of life from the mundane day-to-day to the major stuff like parenthood, family, home, and career. Also loneliness, depression, illness, and death. That may sound like heavy going, but it’s really not. The book is a testament to Rabagliati’s great storytelling skills and deft draughtsmanship, and this makes for an immersive, sensitive, entertaining read.

The book opens in late summer 2012. Paul, Rabagliati’s alter-ego, is a divorced, fifty-one year-old cartoonist living in Montreal. From the outset we see that he’s still dealing with the aftermath of a divorce from some time ago, and spending much time alone, though he generally appears quite content with his own company (perhaps more than he should). His main companion is his cute little dog, Cookie (who sometimes talks to Paul through the magic of cartooning). Paul is increasingly aware of the remorseless passage of time and the inevitable change it brings—change that he struggles against. Major challenges stem from Paul’s important relationships with his mother, Aline, and his nineteen-year-old daughter, Rose. Aline is dying and Rose is soon leaving to study in Europe.

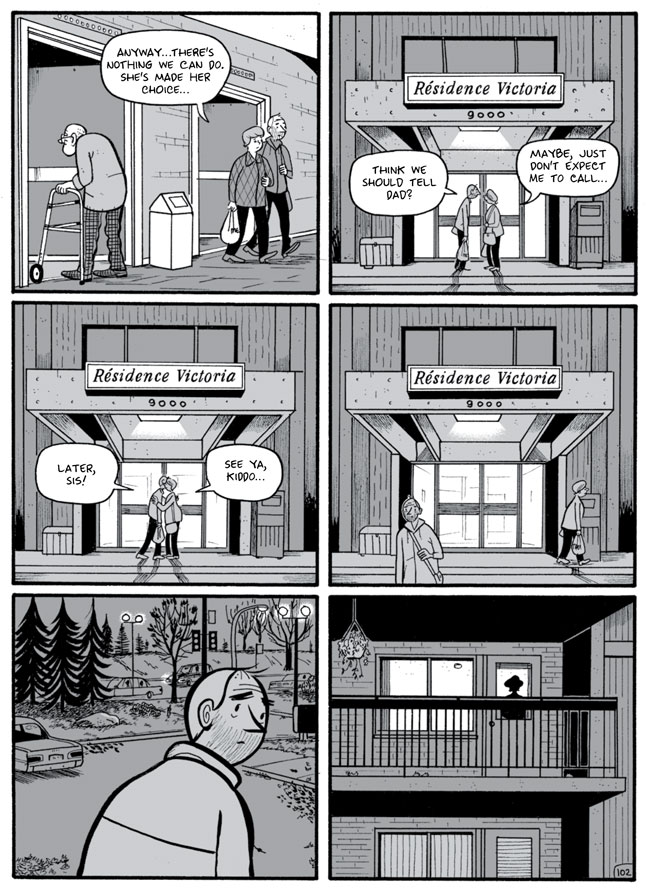

When Aline is diagnosed with cancer she flatly refuses treatment, opting to accept the inevitable: “I’m tired…I can’t do this anymore,” she says to Paul and his sister. “I just want it to end.” Paul admires her bravery, which makes sense in the context of an earlier scene in which he scornfully observes advertising posters depicting retirement as a glamorous life of ease and luxury on yachts: “Who falls for this crap? The truth is, we’re all going to wind up broke and dumped in some old folks’ home, poorly fed and shitting in our pants.” Whether that’s realism or fatalism (or some combination of the two), Paul’s attitude makes it easier for him to accept Aline’s decision. Rabagliati’s drawings deftly accentuate the enormity of Aline’s news by showing Paul and his sister leaving Aline’s apartment in long shots, dwarfed by the Inevitable.

Meanwhile, Rose’s pending departure triggers a renewed sense of helplessness in Paul, who protests vehemently, to no avail. “I’m nineteen, Dad,” Rose has to remind him. “I can do what I like.” Aside from the fact that he’ll miss his daughter terribly, her leaving is just one more big change over which Paul has no control.

Rabagliati applies metaphor with a subtle hand, employing elements of nature to symbolize Paul’s emotional or physical states. The prologue, for example, features a silent sequence of a bird (a night heron as it turns out), standing motionless on a rock at the edge of a stream, peering steadfastly at the rushing water. Other birds come and go, insects flit by, a snail creeps past, but the heron remains perfectly still. Later, as Paul watches the bird, fascinated by its stillness, a woman passing by informs him that the bird is just waiting for its turn to strike.

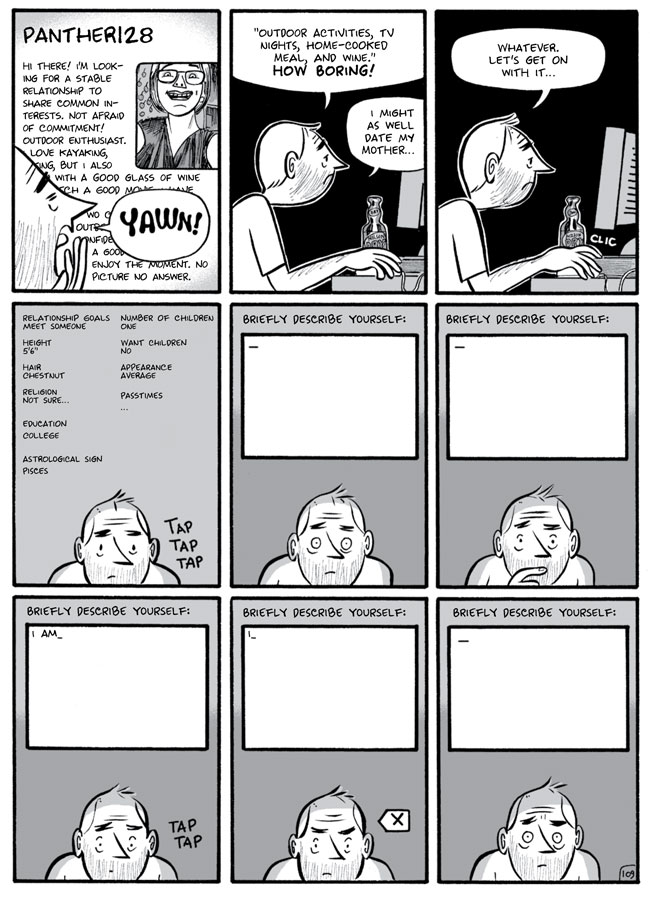

As if spurred on by this exchange, Paul takes action to combat his loneliness: he dabbles in online dating (even though he hates the very idea), and tries to stave off health concerns by exercising (which he also hates). While these sequences offer some rueful laughs, there is a real poignancy in Paul’s efforts. He appears to recognize that to remain static risks becoming completely lost, and that subsisting on memories of happier times isn’t nearly nourishment enough. Though we supposedly gain wisdom through experience as we age, we also become less and less relevant to a culture steeped in youth, beauty, and vitality. Defining oneself can be tricky after fifty, as Paul finds when filling out his online dating profile:

In another vignette, Paul needs a painful cracked molar pulled (emblematic of his increasing middle-aged health issues); simultaneously, a full half of a tree in Paul’s backyard is rotting and must be removed (symbolic of the end of Paul’s past married life in the house). Both his dentist and a yard worker tell him the same thing: “It’s got to go.” Rabagilati cleverly devotes a page with alternating panels depicting the two excisions. Removing both is painful but necessary to Paul’s slow process of moving on.

Throughout Paul at Home Rabagliati’s pacing is leisurely and assured. A good many pages are devoted to Paul muddling through his days, dealing with simple tasks like grocery shopping and going to the dentist, walking Cookie, or drawing in his basement studio. By devoting a page or two to a simple drive to run errands, Rabagliati allows the reader to slow down, to absorb and give in to the activity, to appreciate better the rhythms of life. Rabagliati smoothly intersperses these quotidian moments with more eventful activity, like Paul’s attempt to attach a complicated sleep apnea testing kit to his torso, or when he has to give a nerve-wracking presentation about his comics to an auditorium full of unruly, disinterested middle-school students. Everything flows effortlessly, Rabagliati keeping time with each change in the story’s tempo. His inviting, ligne claire drawings have an immediately appealing, nostalgic mid-century vibe, and his panels breathe with seemingly insignificant incidents and minute visual details that work in tandem with his naturalistic style of storytelling.

As the book draws to a close, Paul visits the stream at wintertime to see that the night heron has finally left its perch. Meanwhile, his story, even with certain events settled, still feels open-ended, ready for the next chapter. There’s an old saying attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci: “Art is never finished, merely abandoned.” This beautifully crafted narrative leaves its hero on a perfect note, and me eager to see what’s next in store for Paul/Rabagliati. While I’m also planning to go back and enjoy some past adventures, Paul at Home stands on its own as a remarkable achievement.

As the book draws to a close, Paul visits the stream at wintertime to see that the night heron has finally left its perch. Meanwhile, his story, even with certain events settled, still feels open-ended, ready for the next chapter. There’s an old saying attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci: “Art is never finished, merely abandoned.” This beautifully crafted narrative leaves its hero on a perfect note, and me eager to see what’s next in store for Paul/Rabagliati. While I’m also planning to go back and enjoy some past adventures, Paul at Home stands on its own as a remarkable achievement.