Aline Kominsky-Crumb, the self-described Yoko Ono of comics—aka "Yoko Buncho"—is back. And this deluxe hardcover reissue of the original 1990 paperback Love That Bunch is a very welcome return indeed.

The new edition features even more vintage comics than the original, plus significant recent work such as the thirty-page "Dream House". Taken together, the stories in Love That Bunch provide a compact, thematically rich autobiography, touching on every important aspect of Kominsky-Crumb's existence: family, sexual obsessions, food, motherhood, art, and various philisophical musings.

She begins with her childhood in a largely Jewish suburb on Long Island, raised by highly dysfunctional, neglectful/abusive parents, then charts her escape into post-college artistic bohemia in the Southwestern desert, then to life in the Bay Area underground comix scene of the late '60s and '70s. In the 1980s, she settles down into relatively sedate southern Californian domesticity with her (in)famous husband Robert Crumb and their young daughter Sophie, before finally moving to a small village in the south of France in the early 1990s. They live there to this day. It's been a long, fraught journey and Kominsky-Crumb tells you all about it, in sometimes mortifying, often hilarious, occasionally moving, but always engaging detail. Lots and lots of detail.

I first encountered Kominsky-Crumb's comics in an old late-'80s issue of Weirdo. Specifically, it was her midlife-crisis story, "Ze Bunch de Pareé Turns 40". I became an instant, rabid fan and began seeking out her work, which I found hilarious, inspiringly candid, complex, and full of personality. Unlike some of her critics, I love her in-the-moment, scrawly, obsessively cross-hatched drawings. Her line appears untrained and often downright crude, but fearlessly committed to paper with a laissez-faire panache. Kominsky-Crumb reflexively lays bare intimate details of her life through her cartoon alter-ego, The Bunch, including explicit particulars of her bodily functions and sexual escapades, along with her fears, insecurities, self-delusions, feelings of guilt, and outright self-hatred. She consistently eschews the idealized, role model-type imagery championed by a particular branch of feminism in favor of self-deprecating but humorous honesty. This tendency earned her legions of detractors from the get-go, but also a small but devoted fan base, which has only grown through the years. To wit: an animated version of Kominsky-Crumb appears as a quasi-fairy godmother in the excellent 2015 film of Phoebe Gloeckner's graphic memoir, Diary of a Teenage Girl, officially sealing Kominsky-Crumb’s rep as a genuine legend of underground comix.

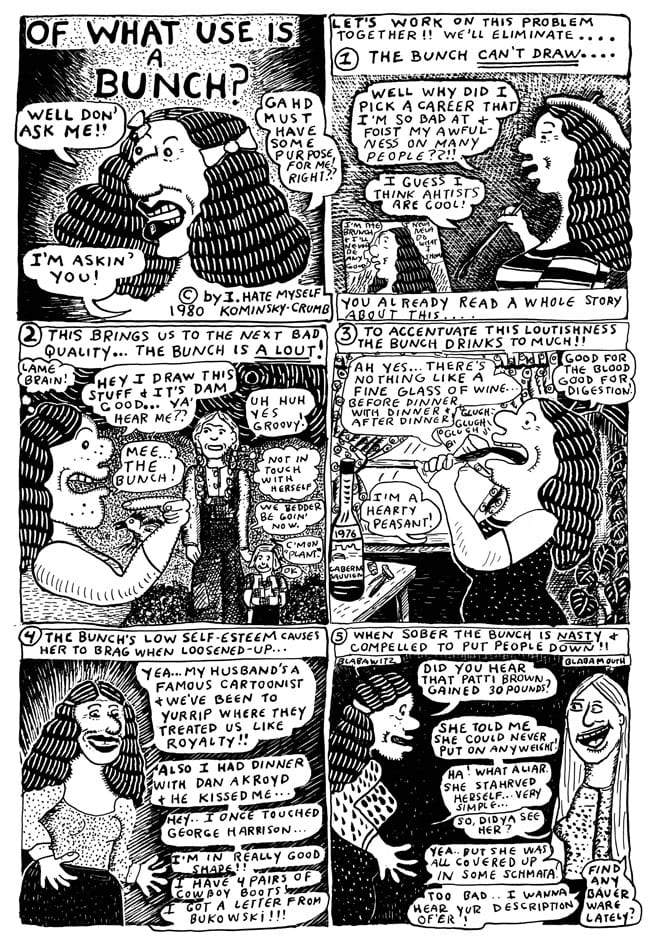

As in the first volume, all the Bunch classics are here. The book begins with early, somewhat harsh tales like "The Young Bunch" (subtitle: "An Unromantic, Nonadventure Story"), in which Bunch is indeed quite unromantically (but explicitly) deflowered in the back of a car by an attractive lout, and “The Story of Blabbette ‘n’ Arnie", a harrowing account of her parent’s unhappy, abusive marriage and the toll it took on Kominsky-Crumb and her little brother. One of Kominsky-Crumb's best-ever comics is the hilarious, warts-and-all "Of What Use is a Bunch?", in which she gleefully demonstrates thirteen reasons why she’s an unworthy person (#7: “She is lazy and self-indulgent”). Another story I've read at least a dozen times is "Why the Bunch Can't Draw", which goes deep into exploring Kominsky-Crumb's tortured relationship to art and creation (more on this story below).

In Kominsky-Crumb's mid-to-late-'80s stories like "Deep Thoughts From my Kitchen" and "Sex-Crazed Housewife”, she depicts her much more stable life as a mostly contented housewife, though she frequently frets over the possibility that she has sold out to bourgeois, middle-class values. “I was once a wild & crazy girl,” she laments, “but now my soul has withered.” The tension between holding on to youthful joie de vivre versus sometimes-boring maturity percolates throughout the stories from this period. That tension, naturally, is not resolved. An undercurrent of all of Kominsky-Crumb's work is the impossibility of reconciling conflicting parts of herself. As funny and funky as she can be, Kominsky-Crumb is a thoughtful writer, one who appreciates and celebrates both her Apollonian and Dionysian natures.

One of the most delightful aspects of The Bunch comics is their personal, conversational touch. Kominsky-Crumb peppers her stories with little asides and footnotes, aimed directly at readers, in a touching or humorous manner. These lend her comics a genuinely intimate feel, like notes jotted down in the margins of a personal letter. In "Ze Bunché de Paree Turns 40", Bunch, finally having realized her childhood dream of visiting Paris, stares tearfully out of the window at the wondrous city below. A box of text points to her: "Overwhelmed by flood of emotion." In the same story, her self-involved mother, Blabbette, phones from America, greeting her daughter with "Aaaaa…?" A footnote explains: "My mother never calls me by my name… Instead it's this long drawn-out 'A' sound with a slight question." In "Why the Bunch Can't Draw", the young Bunch, feeling ignored as she works on a painting, says aloud, "No one cares if I do this… but I'm still gonna!" An asterisked footnote expands on this lament: "I still feel this way."

This story features another hallmark of Kominsky-Crumb's oeuvre. Namely, her fondness for splash panels featuring multiple mini-headlines, stating her themes in bold, satirical fashion. She augments her title “Why the Bunch Can’t Draw” with “Even tho she always wanted to be a ahtist!!!” & “She’s oozing mit talent nevahtheless!!” Meanwhile, the drawing features Bunch working on a painting, assuring herself: “Oh, yes, yes those subtle nuances in the intensity of the facial expressions just right!!” Naturally, all of this contradicts the title, cleverly setting up Kominsky-Crumb as the protagonist and antagonist of her own story (which is often the case).

Kominsky-Crumb’s outwardly crude art has been heavily criticized over the years, particularly early on and often from Robert Crumb fanboys who didn't appear to want to understand her aesthetic for a variety of reasons—including unapologetic sexism or even outright misogyny (check out the letters column in some of the Kominsky-Crumb-edited issues of Weirdo for some examples). The artist herself, in a lively 1990 TCJ interview with Peter Bagge, defines her aesthetic this way: "My cartooning was unconscious and still is. I didn’t contrive or plot to do something in a certain way. It was the only way I was capable of doing it." She goes on to say, "Comics are my worst artwork because it taps into some unconscious and primitive part of me that’s not controlled by intellectual interference. I consider that its strength. I don’t know how to refine that without messing it up." On a related note, when discussing the often scabrous content of her work, she notes, "I don’t romanticize life, and I don’t think that romanticizing women makes other women feel better. It makes most people feel worse." I am down with all of that, 100%.

Kominsky-Crumb's comics are rather generously peppered with misspellings. In the work of most cartoonists this generally drives me to distraction, but with her it feels appropriate to her primitive, done-in-the-moment aesthetic. One curious sequencing error does distract a bit, however. In the 1990 edition of the book, the story "Grief on Long Island" appears right before "Up in the Air with the Bunch", even though it clearly takes place directly after "Up in the Air" (the stories form a two-part anecdote). The sequencing remains the same in the updated book (though this time with a short comic, "The Bunch Du Jour", sandwiched in between). I wonder why no one caught this error and corrected it after all these years. I suppose it's possible that for some reason Kominsky-Crumb wanted the sequencing reversed this way, but I can't discern any aesthetic benefit in doing so. A minor quibble.

The new Love That Bunch comes with a splendid introduction by esteemed comics academic Hillary Chute, who deftly sums up her subject's oeuvre and artistic trajectory, reminding us how groundbreaking Kominsky-Crumb’s work has been and how it paved the way for autobiographical cartoonists—women in particular—to depict themselves with unapologetic honesty. The world has caught on to Kominsky-Crumb's work (the Yoko Ono comparison feels apropos); and it is heartwarming to witness this formerly ignored/maligned artist at last getting her just due. I thought the original book could scarcely be improved upon, but making it bigger just made it better, and richer. I love this Bunch, most definitely.