Hope Larson has been quite prolific over the past two years: two volumes of a graphic novel trilogy called Four Points, twelve issues of Goldie Vance for Boom! Studios and a monthly Batgirl comic for DC. All of these have seen the award-winning cartoonist in a new role as a writer collaborating with other artists. In fact, we haven’t seen her both write and draw a comic since her 2012 adaptation of Madeleine L'Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (the exception being the aptly named Solo, an ongoing webcomic she has been sporadically updating since 2013). Her newest book is a middle-grade graphic novel called All Summer Long, her return to true solo comic making, but she returns as a changed artist.

All Summer Long is an amiable coming-of-age story about Bina – a lanky, offbeat thirteen year old – who must wait out half the summer while her best friend Austin goes off to soccer camp. The two have been best friends since they were babies and usually spend every summer together chalking up points in their “combined summer fun index” where they tally things like “number of cats petted” or “glasses of lemonade sold”. Without Austin around, Bina is at a loss for what to do with herself. She unexpectedly makes friends with Austin’s older sister Charlie, who tries introducing her to teenage concerns like babysitting and boyfriends, but Bina is more concerned about the aloof text messages Austin is sending from camp and what that means for their friendship.

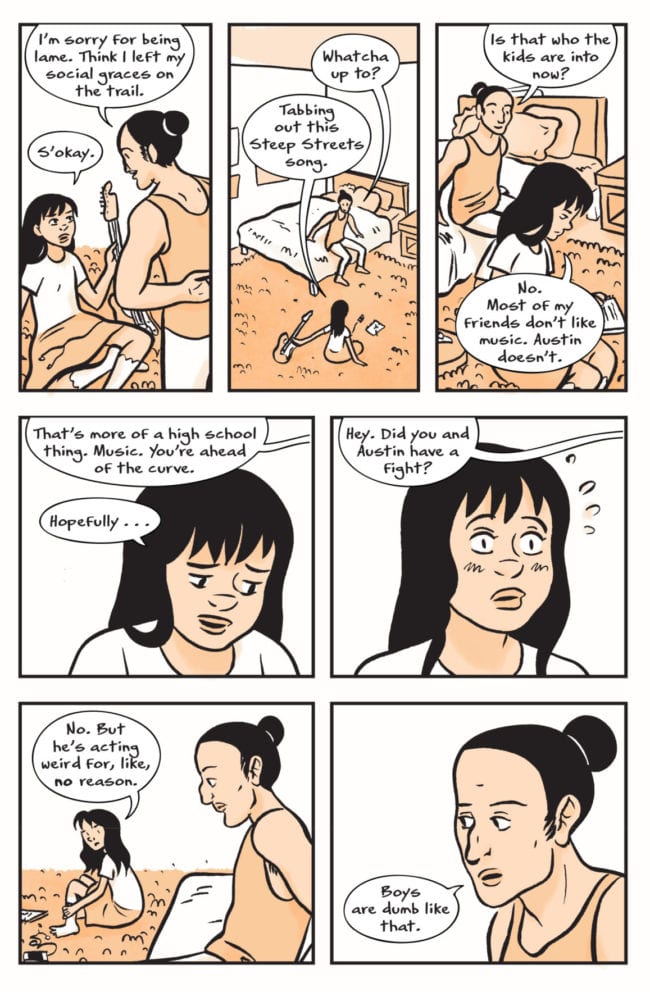

When Austin first leaves for camp, Bina spends her first week alone doing nothing but binging so much “Infiniflix” (the off-brand Netflix in this Larson-verse) that her parents have to change her password to cut her off. She loves music and playing guitar but it’s an interest that isn’t shared by Austin. It takes a transformative experience at an indie rock show, talking to a female lead singer, to make her realize that it is she alone that can make things happen for herself. Although Bina and Austin’s relationship is not romantic in nature, there is an inherent warning about being codependent that Larson is imparting to her young, female readers. Girls sometimes give up too much of themselves in their early relationships – whether with boys, girls or platonic friends – only to end up with nothing in the end. Bina, for her part, doesn’t show any romantic interest in boys at all, which makes this work as both queer lit as well as everything-doesn’t-have-to-be-about-boys lit.

Larson does a great job in defining Bina’s growth from the beginning where she is a needy, uncertain naif to the end when she is starting her own rock band. When her mother gives Bina her old leather jacket she imparts the book’s big lesson to her: “You’re more you every day. That’s going to draw people to you, and it’s going to scare some away, but..” until Bina interrupts: “Their loss.”

Larson does a great job in defining Bina’s growth from the beginning where she is a needy, uncertain naif to the end when she is starting her own rock band. When her mother gives Bina her old leather jacket she imparts the book’s big lesson to her: “You’re more you every day. That’s going to draw people to you, and it’s going to scare some away, but..” until Bina interrupts: “Their loss.”

Thirteen is a tricky, transitional age. It’s a time when a child’s knowledge and experience can’t answer the questions being asked by their crazy, new emotions. It’s also a rich age to write about because everything is an unknown mystery to solve. Kids at that age read books like this voraciously to store up the clues they’re going to need when they star in their own future coming-of-age stories.

Larson is a contemporary of Raina Telgemeier – to whom all middle grade level authors are inevitably compared – in that both came from the world of webcomics in the early 2000s, each having influenced a generation of young comic creators who are just entering the industry now. Where Telgemeier’s highly relatable memoir comics are as mainstream as a Taylor Swift song, Larson has always been a little more like, say, Neko Case in comparison: a little more challenging, a little more artistic. She started out making comics like Salamander Dream and Gray Horses that showed a distinct style of fanciful drawings with hand-drawn sound effects and lighter-than-air word balloons with tails that would twist into curly q’s as they pointed towards a character’s mouth. After her Eisner Award winning adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time, Larson took some time off to direct (a music video and a small, independent film called Bitter Orange) and to focus on collaborating with other artists and writing a wider variety of books.

The art in All Summer Long is much more workman-like than we used to see from Larson. Mostly gone are the experimental layouts, twirly balloon tails and decorative embellishments; replaced with digital lettering and simple panel arrangements. You can argue that she’s shaken off unnecessary flourishes that only distract from the story and that might be true. It also seems like she is cutting a lot of artistic corners to just get the book out there. It’s tempting to say that, like Bina, Larson has lost a little bit of herself, but her recent collaborative work has allowed her to find a new self as writer who is very good at telling stories that she is just not the right person to draw. It seems like she has so many great books in her future, but her heart may not be in making them alone anymore.