For 40 years, Gilbert Hernandez has been one of the most prolific and versatile cartoonists on the planet. Of course, he’s best known for his many Palomar masterpieces, but in more recent years (if you consider the last couple decades “recent”), he has taken readers on a wild rollercoaster ride through lurid worlds populated by punks, perverts, and psychopaths. Most of these stories feature Fritz, a “vamp” B-movie actress whose hourglass figure and “blimp tits” have earned her a cult following.[1] While Gilbert often explores Fritz’s troubled life off-screen in Love & Rockets, for years he has also been “adapting” her exploitation films in various forms, including a series of standalone graphic novels. Of the ten B-movies that he’s published thus far,[2] “Hypnotwist” has been a “personal favorite” since I first read it in Love & Rockets: New Stories #2 back in 2009. Now, 12 years later, it’s (finally) been re-released along with “Scarlet by Starlight” (from New Stories #3) as a double-feature flipbook.[3]

In “Hypnotwist,” Fritz plays a time-travelling illusionist who drifts through her own past and future, reliving the various traumas inflicted upon her by a coterie of unsavory men. It would be easy to slap labels like “dreamlike” or “cryptic” onto “Hypnotwist,” and indeed these are apropos, but the fact that the story feels fragmented and confusing is intentional. Its opaque plot and enigmatic symbols are vintage pop surrealism a la David Lynch. Like Mulholland Drive or Twin Peaks, the story is murky, teasing profundity but never quite coalescing, instead forcing readers to project myriad possible meanings onto it. It’s the kind of off-kilter story that makes you flip back and forth, searching for connections that are only hinted at. Reading it is like trying to solve five different jigsaw puzzles all mixed together. But trying to crack its code is a bad idea, like conducting an autopsy to find a soul. This film sits comfortably on the fringes of comprehension.[4]

But what makes “Hypnotwist” stand out is its silence. Not only is it a tribute to the silent films and cartoons of the ‘20s and ‘30s, its wordlessness reinforces the amateurish quality of the movie (this was a shoestring production, after all). Its silence also shines a fresh spotlight on Gilbert’s cartooning. While his figures and compositions have simplified over the years, he’s lost none of his creative potency. Rather, his minimalist panels are designed to be absorbed quickly, moving readers along like an actual silent film. Throughout the story, Gilbert’s quietly phantasmagoric drawings pull off one dazzling high-wire act after another, maintaining that essential balance between wonder and disgust. In one particularly memorable scene, for example, float handlers in some unseen parade dangle precariously above the city, clinging to the tethers of a runaway giant cat head before, one by one, plunging to their deaths.[5] It’s an outlandish tragedy, but the scene’s silence warps the calamity into a demented comedy, mixing the horror with the slapstick hijinks of a Saturday morning cartoon.

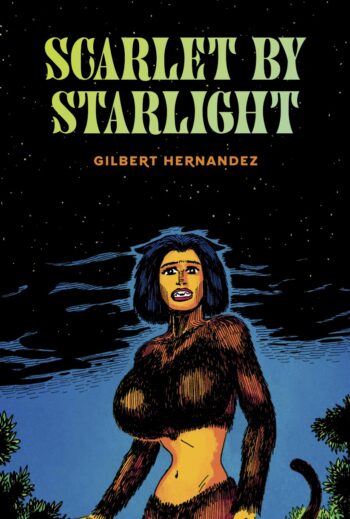

“Scarlet by Starlight,” the other half of the twin bill, could have been titled “Fritz the Cat” if that name wasn’t already taken. Indeed, “Scarlet” has a lot in common with Crumb’s controversial classic, and was no doubt intended in part as an homage to one of Gilbert’s favorite cartoonists. In this low-budget thriller, Fritz plays a lustful cat creature -- a buxom bastardization of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Grizabella -- who becomes enamored with an insolent human scientist. It’s a perfect B-movie premise, and, as usual, Gilbert lets his id run rampant on the page, but the story’s aggressive depictions of sodomy and bestiality are so over-the-top, they transform the ‘60s sci fi schlock into an onslaught of carnality and violence.

“Scarlet by Starlight,” the other half of the twin bill, could have been titled “Fritz the Cat” if that name wasn’t already taken. Indeed, “Scarlet” has a lot in common with Crumb’s controversial classic, and was no doubt intended in part as an homage to one of Gilbert’s favorite cartoonists. In this low-budget thriller, Fritz plays a lustful cat creature -- a buxom bastardization of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Grizabella -- who becomes enamored with an insolent human scientist. It’s a perfect B-movie premise, and, as usual, Gilbert lets his id run rampant on the page, but the story’s aggressive depictions of sodomy and bestiality are so over-the-top, they transform the ‘60s sci fi schlock into an onslaught of carnality and violence.

There’s no denying that both stories in this flipbook obliterate the boundaries of decency; they are a blitzkrieg of repulsive imagery and sadistic characters. So it’s not surprising that the book would garner some haters. One less-than-enthusiastic Goodreads reviewer, for example, described it as “literal garbage that should not exist, much less earn a publication.” But this kind of conservative perspective misses the point. American culture is already drowning in smut. With the internet, the unimaginable perversions of yesterday have become commonplace today (and have you watched the news lately?). What Gilbert does so well is sift through all this “literal garbage” and craft it into compelling and original stories. The challenge is that audiences today are so desensitized to sex and violence, what was once taboo has become normalized, and even boring. What makes Gilbert’s work so enthralling is that, rather than succumb to these tired clichés, he embraces this cultural devolution by dragging readers deeper into the abyss of his imagination.

Whether this kind of absurdist depravity offends you or not will depend on your particular point of view, but offensive art is not the same thing as bad art. In fact, offensive art is often more impactful than traditional works. For example, modern artists like Marcel Duchamp shook up the establishment with art that was intentionally provocative. While Gilbert may not have such lofty ambitions (anymore), his Fritz stories nonetheless have a similar polarizing effect, alienating some fans while delighting others. Yet, from Tijuana Bibles to underground comix to Batman’s penis, there is a long-standing tradition of offensive art in comics and Gilbert is one of its masters. Obviously, his brand of hardcore punk grindhouse is not for everyone, but for those who appreciate the grotesque beauty of these B-movie books, this is one of the best in the series.

* * *

[1] Rosalba “Fritz” Martinez is Gilbert’s oldest and most fucked up character. She first appeared briefly in “Music for Monsters” in the first issue of Love & Rockets. According to Gilbert, “[Fritz] was actually the first character I made up, back when I was in my early twenties, or actually my late teens. She was the protagonist of a science fiction series I was going to do. But I lost interest in that” (Brian Heater, 2007). Her name and physical appearance are a combination of Ernie Bushmiller’s classic comic strip character Fritzi Ritz, and R. Crumb’s salacious feline Fritz the Cat, an icon of the '60s & ‘70s underground comix scene and the subject of the first X-rated animated film in history.

[2]To date, Gilbert has published ten of Fritz’s B-movies: Chance in Hell; Speak of the Devil; The Troublemakers; Hypnotwist/Scarlet by Starlight; "King Vampire" (New Stories #4); Love From the Shadows; "Proof That the Devil Loves You" (New Stories #5); Maria M.; and "The Magic Voyage of Aladdin" (New Stories #7-8). However, the endpapers hint at a much larger oeuvre of films, and in The Love & Rockets Companion he listed 24 distinct movies that Fritz appeared in (and that was in 2013!).

[3]Gilbert often makes changes to his work when it’s collected. With “Hypnotwist”, he added more than a dozen new pages making this edition, in a sense, the film’s final director’s cut.

[4]The disjointedness of “Hypnotwist” was explained in a series of vignettes, including “Sad Girl” in Love & Rockets: New Stories #2. According to Killer (Luba’s granddaughter), it was a lost film from Fritz’s early days which languished unfinished for years. As she explained, the movie “was filmed out of sequence over the span of ten years.”

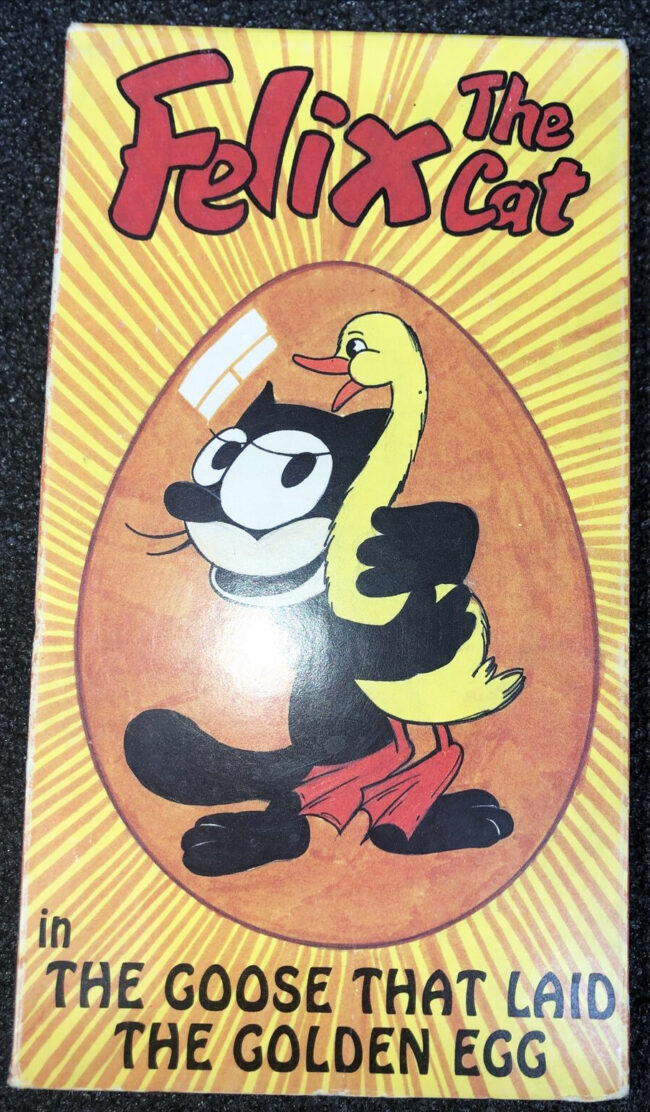

[5]The grinning, ill-fated parade float is the head of Felix the Cat from The Goose That Laid the Golden Egg (1936). Otto Messmer’s Felix was one of the earliest animated characters, debuting in 1919, nine years before Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie. Gilbert’s subversion of vintage cartoons pushes “Hypnotwist” into Al Columbia and Jim Woodring territory.