Honey #1 is an elegantly drawn, exuberantly paced, spectacularly colored workplace dramedy/romance. It's an action-adventure story set in a fantasy-indebted world with prominent horror elements. It's a radical reconsideration of anthropomorphism and "funny animal" comics. It's a serious exploration of how communities shore up certain strengths of the individuals they comprise while also pushing them all toward willful ignorance of wrongs committed in their name. It's a gedankenexperiment about an all-woman society -- imagining it, putting it through its genre-story paces, examining female friendship, romantic relationships, and enmity in the fresh air created by the near-total absence of men and the complete absence of men in positions of power. It's hugely, admirably, refreshingly ambitious for a twelve-page comic book. If the work cartoonist Céline Loup assembles from these myriad parts is not without flaw, that's almost beside the point.

Honey is set among a group of worker bees on a mission to collect pollen outside their hive that brings them into contact with other, rival species, namely butterflies and wasps. And simply on the "huh, what a good idea" level, this is Loup's most striking and entertaining innovation: They're pretty much just human women. The stripes on the jumpers worn as uniforms by the bees are as much of a nod in the direction of insectoid features as Loup gives them -- no wings, no antennae, no stingers. The wasps are a bit creepier, more stylized, but this broadcasts their villainy, not their bug-ness; their sleek black bodysuits, wrap-around shades, tight black ponytails, and towering height make them look like the Terminator. Only the butterflies retain any characteristics of their real-world counterparts, but their gossamer wings are joined with long serpent tails that end in a fish's tail-fin, which together with their bare breasts and their fangs evokes a mermaid, a siren, a harpy; the bees seem to see them as animals, and they look the part. Like a bizarro Maus -- Art Spiegelman gave his characters animal heads but in every way intended them to be seen as people; Loup draws her characters as people but intends them to be anthropomorphized animals -- Honey is pushing at the boundaries of the funny-animal form. Quite independently of whatever else is going on in either of these comics, watching artists roll up their sleeves and say "okay, let's see what else this thing can do" before tackling a genre is an entertaining proposition.

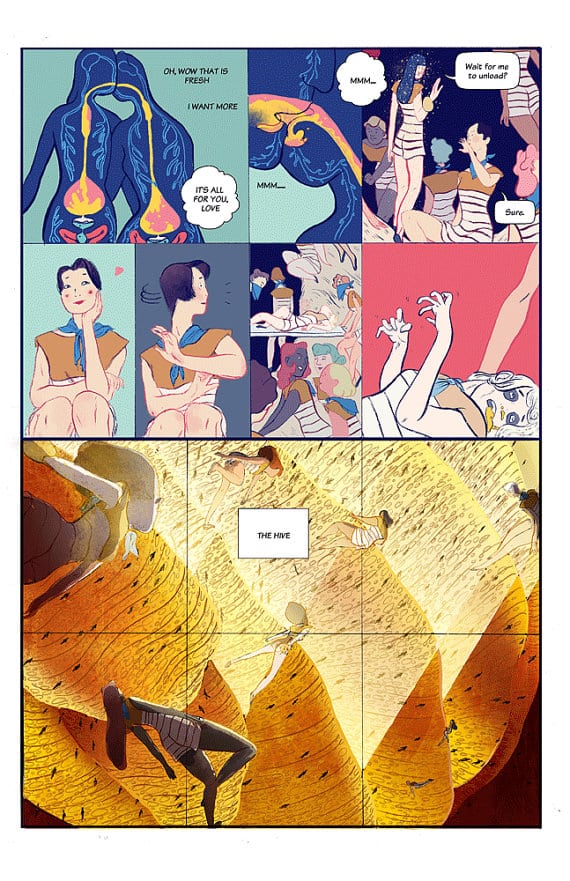

The crux of the comic's conflict is a the-personal-is-political situation involving two romantically involved young workers, confident veteran Bea and empathetic rookie Delia. Their initial scene together is loving and sensual, as Bea helps Delia put aside her first-flight jitters with a nectar-infusing kiss Loup depicts down to a biological level. These panels, where the pair are depicted as black silhouettes with their internal organs revealed in bright colors within, feel like a tip of the hat to Michael DeForge's body-horror-tinged insect-world allegory, Ant Colony. In some ways, Honey reads like Loup's translation of DeForge's neon nightmare into the lush illustrative idiom associated at a glance with her alma mater the Maryland Institute College of Art. This style's emphasis on inviting but dynamic colors, attractive figures, and strong science-fantasy costume and character designs has proven a natural fit for thoughtful genre work as seen in the oeuvre of fellow MICA grads like Kali Ciesemier and Sam Bosma. It should be noted that this isn't just slick illo work shoved into sequential form. Loup's line (sometimes thin, other times a Tamakiesque brush swoop), her gutterless grids, and her rock-solid grasp of an extremely broad color palette guide the eye easily around the page. The only obstacles to clarity are the digital lettering and after-the-fact word-balloon placement, the best thing about which you can say is that you stop noticing how slapped-on they feel after a few pages.

But even before we get our first glimpse of the Hive -- rendered by Loup's colors as radiant, golden, glorious honey-hued paradise -- Delia gets a reminder of the dark side of her culture. She's interrupted mid-swoon by a glimpse of an older worker -- her hair ghost-white, her eyes a pair of shiners, her mouth and nose leaking nectar, her hands and arms in a cataleptic rigor -- being carted away by some of her sisters for eventual discarding. To Delia, this unceremonious end -- which, as Bea points out as they debate it, is a peaceful one compared to other horrors that can befall them outside the hive -- renders their happiness a kind of sick joke. Their lives may not be solitary and poor -- the close bonds of the sisters and the riches of the Hive see to that -- but this is a smokescreen that obscures a reality that is nasty, brutish, and short nevertheless.

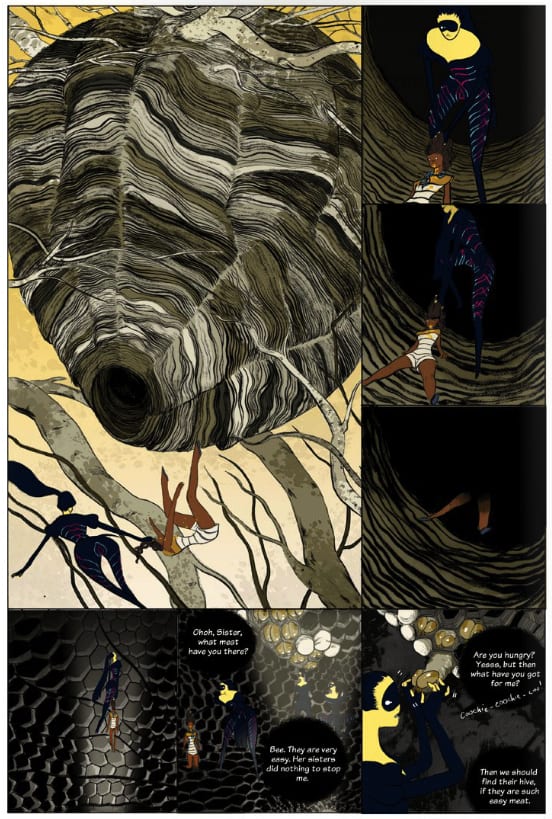

The argument escalates as they fly out to work, eventually triggering a pheromone response within them both that blackens their skin and their mood alike. But an external menace, the banshee-like butterfly, intervenes before those pheromones can be broadcast to other workers, triggering similar responses from them. Instead, another pair arrive, one that includes Bea's old workmate Edith. Fuming with jealousy, Delia initiates a nectar kiss with Bea, shooting daggers at Edith with wide-open eyes the whole time. Yet again, the drama is interrupted by a monstrum ex machina, though this time the outcome is far worse -- a black-clad wasp, her eyes obscured by a menacing black visor, drops in out of nowhere and iimpales Edith's face and neck with her limbs. As the others watch helplessly, Edith, oozing nectar and tears, is dragged back to the wasp nest. This is Loup's single most impressive image, especially in contrast with the solar splendor of the beehive: the nest is a black and grey vortex, its walls constructed from layer upon layer of ominous waveforms like the cover for a Joy Division record. The fate that awaits Edith inside -- it involves a pair of gardening shears and the sound effects "SNIIIIIIIIP SNIIIIIIIIP" -- is worse than death. To Delia, whose continued argument with a disconsolate Bea is juxtaposed with Edith's destruction, it's evidence of her own rectitude regarding the brutality of life; to Bea, it's an indication that Delia is toxically self-centered.

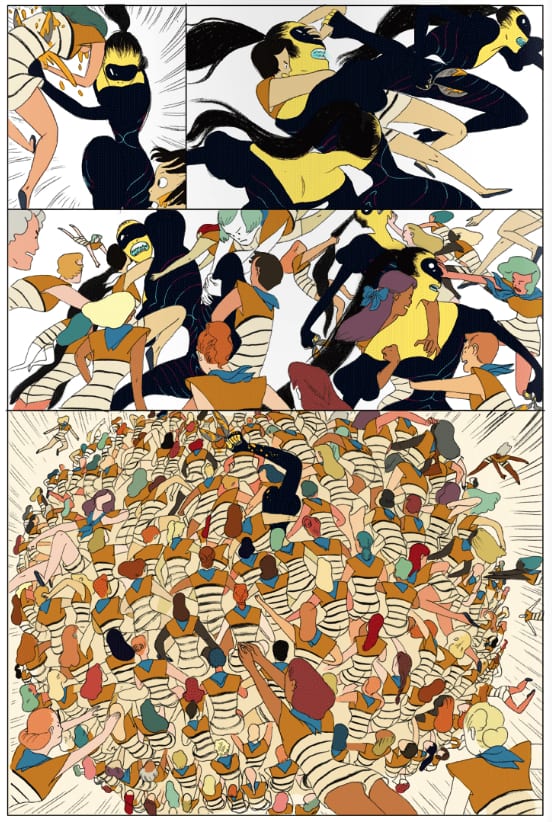

The context of their rapprochement is the comic's most challenging element. Delia and Bea make up in the middle of gang-tackling a trio of wasps, sent to raid the hive after Edith proved it a tantalizing target. Loup draws the swarm as a massive ball of faceless bee bodies, a subliminal synthesis of the previous shots of the hive and the nest. Their charge is based on a real-life tactic in which bees kill invading insects by surrounding them and raising their own collective body temperatures high enough to cook the intruders alive. Such an vivid example of Nature red in tooth and claw could, and perhaps should, be expected to illustrate a point about the savagery of state violence. Here, though, it serves to unite the briefly sparring lovers. When Delia starts apologizing for blowing off Bea's concerns, Bea interrupts her to apologize for having been so didactic about them. "Even still, it is insane, the things we have to get used to," Delia offers. "Yeah, but...," Bea replies, awakened by the invasion to the occasional necessity of brutality, "I think I can sleep a little easier after seeing what the hive can do if we get pissed off enough." Rest easy, citizen, the hive will keep you safe!

The final panel, however, may offer a humorous self-critique. "I mean, did you even know this happened?" Bea asks as she and Delia watch the roasted wasps plummet to their deaths. "Holy shit." "It's pretty fucking cool," Delia agrees. These are the first obscenities anyone has uttered, and the sudden incursion of coarse contemporary language and locution hits like a cream pie in the face. Perhaps this goofy exchange serves to acknowledge that narratives of redemptive violence are ridiculous as well as destructive; perhaps the rapprochement-through-killing is intended to be ironic rather than empowering.

Or, more pointedly, it may capture the catharsis of creating, to borrow a powerful phrase from Loup's searing comic and blog entry on the topic, "a world where men have no stories." It's certainly possible to create a matriarchal alt-fantasy world involving an off-kilter approach to anthropomorphism that depicts war and violence in a non-didactic but unmistakably condemnatory way -- Megan Kelso's masterful Artichoke Tales makes that clear. But after centuries of stories in which men formed friendships and created cultures, made enemies and encountered invaders, and violently defended the former against the latter without a country care for the lives, needs, desires, and stories of women, putting the combat boot on the other foot for twelve fucking pages is hardly too much to ask. Of course, it's not being asked -- it's simply being done. If some nuance is lost in the adrenaline rush, ¯\_(シ)_/¯ . This is only issue #1, and Loup has promised further exploration of the world she's imagined. There's more than enough nectar to survive on in here till then.