T. Edward Bak's Wild Man series initially ran in the pages of the anthology Mome. In this first volume of his story about the German naturalist and explorer Georg Steller, he's altered the format and some of the content considerably than what was published in Mome, and created a far more coherent and powerful experience. On the surface, a historical comic about Steller and the Second Kamchatka Expedition and the harsh winter conditions he and his team faced is a fairly straightforward idea. Bak is not interested in a straightforward presentation, however, and instead carefully uses a number of techniques to expand on his themes.

The theme that Bak most frequently turns to is Steller's firm belief that humanity is not set above nature but rather represents just another aspect of nature. Bak elegantly creates this contrast through his use of color and time jumps. The book begins in media res with Steller and the crew on what would eventually come to be known as Bering Island, as Steller's restless mind turns to the wonders he has seen. The species of plants and animals that he has categorized are lovingly rendered in color, thus underscoring Steller's focus on science above all else, even as that science takes many forms. Indeed, as is alluded to later in the book, Steller managed to cure the scurvy suffered by many of his crew thanks to the use of herbs he learned about through the Kamchatkan natives, whose customs and knowledge he greatly respected.

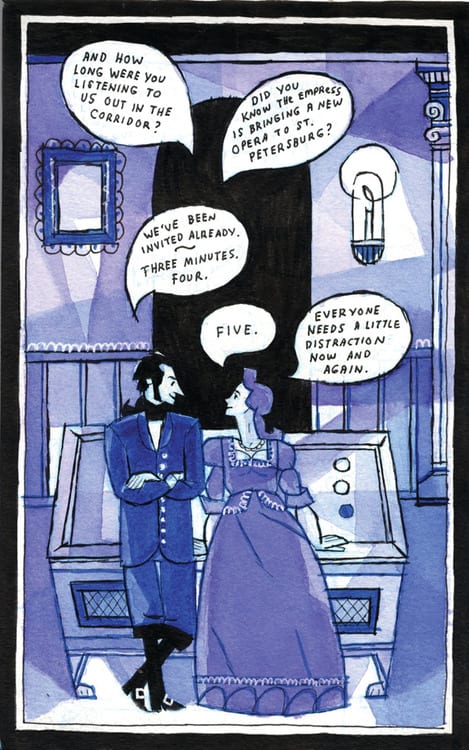

Bak then flashes back to St Petersburg and the almost effete presentation of life amongst the privileged, educated, and wealthy in Russia. When depicting conditions in the wild, Bak uses a harsh black and white technique that has a heavy emphasis on spotting blacks. It's a bleak, almost apocalyptic world where the manners of men break down quickly and civilization goes out the window. By contrast, the scenes in St Petersburg are in color, using soft, single- and duo-tone pastels. The purples, teals, pinks, and blues create an almost stained-glass-like effect, making each panel look backlit. That effect is especially heightened in one panel where Steller and his wife Brigitta embrace; it's practically a Valentine Day's card worth of pinks and reds. The stained-glass effect is heightened because Bak uses each page as a single panel, as he wants the reader to linger on particular images and events.

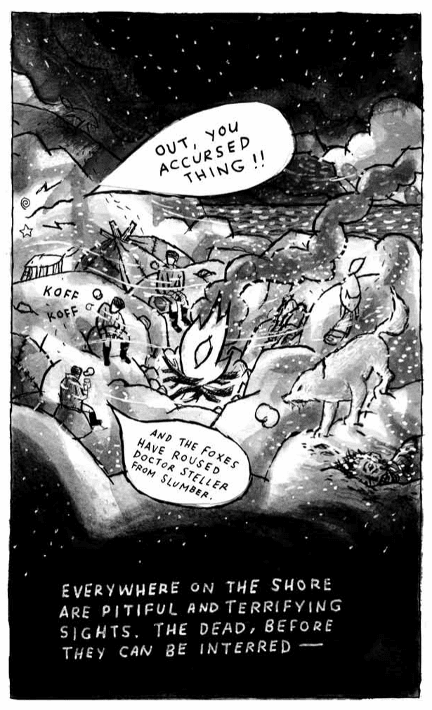

Without resorting to a typical infodump to explain the historical backstory, Bak still manages to reveal quite a bit about Steller. As depicted in the book, Steller is an iconoclast, decrying a fellow scientist for deferring too much to his belief in God (and fearing sex). He clearly sees his wife as an equal and is entirely devoted to her. On the trip itself, he's no shrinking violet; in fact, he's always agitating to explore wherever he happens to be. In the most striking sequence of the book, Steller is torn from a sex dream with his wife by one of the marauding blue foxes that plagued his party. The page where he regains consciousness is mostly drained of color, save for a light purple wash on Steller and the tiniest of blue tint around the fox's teeth. It's a clever effect on several levels, giving a color hint with regard to the blue foxes as well as blurring the realms of sleep and wakefulness.

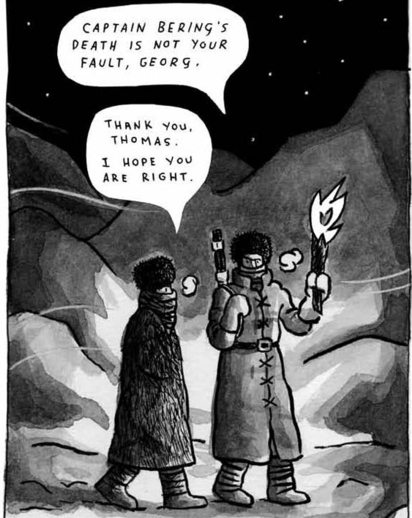

The rest of the first volume sees Steller interact in greater detail with what's left of the party. From scientists to explorers to sailors, the stranded group deals as best they can with the harsh environment. Steller regards their gambling as a foolish waste of time, even as he couldn't care less about matters like class status in this environment. Steller hints at his wife staying behind with their child after initially agreeing to come with them while arguing about the nature of civilization and god with the members of the crew. Asking "What if it is we who are the savages?" when the Kamchatkans are brought up, Steller refuses to give any special favor to the civilization from which he came. Despite his cynicism, Steller is an inspiring figure because of his relentless curiosity and optimism, even in the worst of conditions. He takes each moment out in the wild as a learning opportunity and is shown to be constantly writing and making other crew members draw the wildlife.

The last few pages show Steller as a boy and how he initially began his life as science. Asked what was so interesting by one of his parents, his unspoken answer is "everything." Every aspect of nature, from birds to trees (and later, to how natives interacted with their land) was of keen interest, as Bak so eloquently yet minimally depicts. The key to Bak's success in this volume is restraint. The title refers to the flood of memories that came to Steller while on the island, both recent and dating back to childhood, as Steller clearly understands that every moment of misery was also a chance to observe something for the first time by a Westerner. Every moment was a chance to truly experience the raw power of nature and understand how small he and his crew were in the face of the conditions and the native wildlife. Steller is an agitated figure and one depicted as possessing a quick temper, yet Bak depicts the joy and endless curiosity that are always in effect for him. This first volume barely scratches the surface of Steller's life, his accomplishments, and the expedition itself but provides the reader a strong sense of who he was, what he believed in, and why he was important. This was a scientist who was an atheist but had a deep appreciation and respect for the natives he encountered, seeing them as the repository of a different kind of knowledge. That made him an iconoclast among his peers but is at the heart of why he was a great scientist: respect and understanding that he affects what he observed.