Noah Van Sciver has long been one of my favorite cartoonists. I’ve championed his work in a number of venues over the years, and he’s been consistent both in terms of prolificacy and of marking milestones of gradual but implacable improvement with every subsequent release. Not every good cartoonist gets the luxury of prolificacy in these waning days of the American experiment, so it’s worth noting when you find it. It is because of my deep respect for the man behind Fante Bukowski - or as it’s called in my house, Why Did You Make A Comic Book About My Mid-Twenties? - that I have recently read a comic book about the Grateful Dead.

I know, I know.

The Grateful Dead were a rock & roll band who got their start in the mid-1960s, playing shows in and around the Bay Area during a famously fecund period in the history of popular music. Came up with the likes of Big Brother & the Holding Company and Jefferson Airplane, performed at Woodstock (though they’re not in the film so you wouldn’t know). The band’s estate still does brisk business, having successfully and rather improbably managed to sell the Dead to subsequent generations. You still see Deadhead stickers on Cadillacs, sometimes even taped over Black Flag decals.

Now, I haven’t really been a music writer of any note for a decade, so my union card is out of date. Seemed like it became cool to like the Dead again right when I started to ease out of the field. Stephen Malkmus has always been a fan, and for some reason he was talking about the Dead a lot around the promotional tour for Real Emotional Trash (he may have discussed the band earlier, but that was where the influence became pronounced enough to be discussed). It stuck out to me at the time because it was a late example of precisely the kind of semi-ironic revivalism that had typified hipster curatorial discourse throughout the 90s, a time when the so-called guilty pleasures from past decades could only be smuggled back into the mainstream with proverbial oven mitts. Think about how it became cool to like the Carpenters in the early 90s, after Todd Haynes’ Superstar in ‘87 and Sonic Youth’s quaalude-tastic “Superstar” in ‘93 blew the doors open. Only this wasn’t some previously discarded slab of AM Gold whose virtues stood undiminished by parody. This wasn’t just any critical reassessment.

This was the Grateful Fuckin Dead! Game over, man!

It’s like you weren’t even paying attention to SPIN lo those years ago. (And you’re really not ready for the conversation about the enduring outsize influence of Sean Landers’ “Genius Lessons” on American cartooning.) The era of the semi-ironic guilty pleasure came to an abrupt end at the waters’ edge of the Aughts, and in hindsight it should come as little surprise that those waters were the Dead. Besides, you think, tumblers falling in the back of your mind like a key falling into an ancient lock, the clues were there all along. Go back to 2000 and that turn-of-the-century touchstone Freaks and Geeks - an ur-text of the fin de siecle if ever there was - and even then, there it was, a copy of American Beauty tucked into Linda Cardellini’s backpack in the last episode.

It’s like I’m in that meme, you know the one. It’s got two astronauts in it and one astronaut is pointing a gun at the back of another astronaut’s head. The first astronaut is looking at the planet Earth but it’s actually the Grateful Dead’s skullhead logo, saying, “Everyone’s a Deadhead.” The second astronaut replies, “Always have been.” He pulls the trigger, fade to merciful black.

It’s like I’m in that meme, you know the one. It’s got two astronauts in it and one astronaut is pointing a gun at the back of another astronaut’s head. The first astronaut is looking at the planet Earth but it’s actually the Grateful Dead’s skullhead logo, saying, “Everyone’s a Deadhead.” The second astronaut replies, “Always have been.” He pulls the trigger, fade to merciful black.

Could it be that the gen-x backlash that fueled the critical dismissal of so many of the most prominent 60s and 70s rock acts in the decades since is actually just the same kind of resentful butthurt that made comics critics (such as myself!) so instinctively skeptical of... prominent 60s and 70s cartoonists in the decades since? Because skepticism is necessary. It’s important to tip at sacred cows. It’s important to have personal standards, likes and dislikes - just so long as you recognize they’re not universal, and if you’re a critic - slave as you may be to your own hollow prejudices! - to act accordingly and responsibly. That took me decades to learn, and it’s also why I’m not eager to return to writing music reviews. I no longer find within me the same generosity of spirit for bad music as I do bad comics. Or, if not bad per se, definitely not my cup of kombucha.

All of which leads me back to the object of our discussion today - Grateful Dead Origins. Did you know that Jerry Garcia’s real name was James Howlett? Apparently so.

(Low hanging fruit? You betcha!)

Perhaps I’m biased against music comics in general. It never really works the way cartoonists want because it’s an attempt to replicate an irreplicatable sensation in one medium through another medium. (It is similarly difficult to write good pop songs about comic books, to be fair. Is there even one? Besides R.E.M.’s cover of “Superman.”) For proof of this principle I offer for example an earlier volume of similar musical biography, Bill Sienkiewicz and Martin Green’s Voodoo Child GN. Did you even know that Billy the Sink had done a biography of Hendrix - even more, that much of the book was laid out by Will Eisner? I bought it when it came out back in 1995 and it struck me as a noble failure, as much as anything. It’s pretty to look at. How the hell do you draw a sound? People try. Sometimes it’s fun to watch them try to the impossible.

Perhaps I’m biased against music comics in general. It never really works the way cartoonists want because it’s an attempt to replicate an irreplicatable sensation in one medium through another medium. (It is similarly difficult to write good pop songs about comic books, to be fair. Is there even one? Besides R.E.M.’s cover of “Superman.”) For proof of this principle I offer for example an earlier volume of similar musical biography, Bill Sienkiewicz and Martin Green’s Voodoo Child GN. Did you even know that Billy the Sink had done a biography of Hendrix - even more, that much of the book was laid out by Will Eisner? I bought it when it came out back in 1995 and it struck me as a noble failure, as much as anything. It’s pretty to look at. How the hell do you draw a sound? People try. Sometimes it’s fun to watch them try to the impossible.

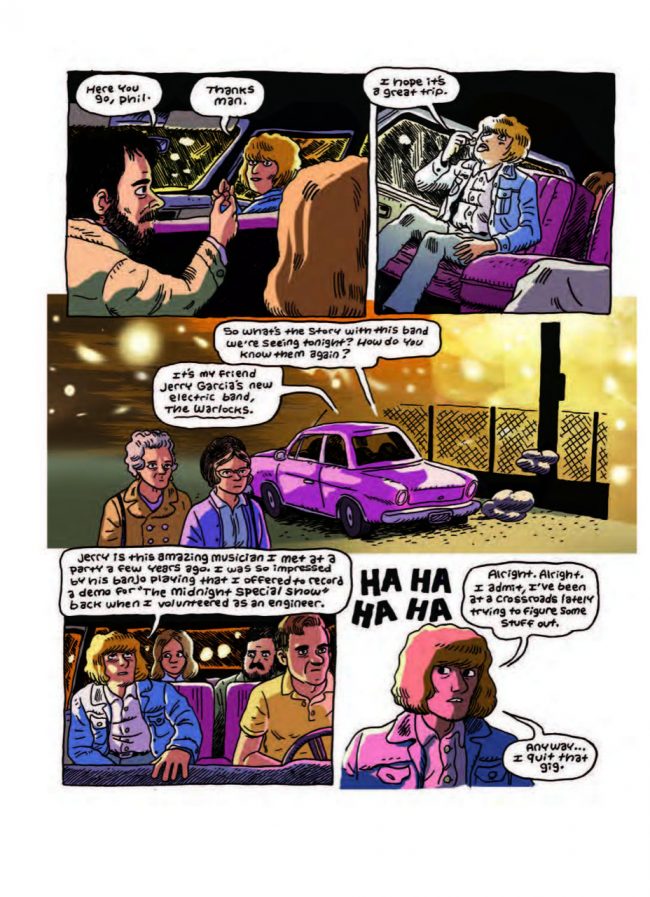

Van Sciver tries pretty good, it must be said. Coming to the book from the perspective of someone with, if we’re being blunt, pretty much zero desire to ever again have to think about the Grateful Dead, it was a very pleasantly readable narrative. The word I come back to over and again with Van Sciver is “pleasing” - perhaps that seems an humble or even dismissive descriptor? I like his lines. His pen is extraordinarily expressive. It’s fun just to pick out panels and look at all the little texture lines he draws on everything. Never extraneous, just the perfect amount to make his very loose cartoony figures seem as if they exist on the page in full dimension, with depth and mass.

Origins doesn’t hold together as something that necessarily has a beginning, middle, or end - this is very much the story of five years in the life of a clutch of dudes who find rather precipitous success under the most improbable business model. Written by Chris Miskiewicz, the book flows pretty well considering how choppy these kind of biopic projects can read in comics form. One event leads inexorably into the other as the Dead gradually coalesce from their earliest incarnation as The Warlocks through to the lineup that recorded their first albums with Warner Brothers. It’s fairly frictionless, as these things go - there just happened to be a critical mass of talented musicians in and around the Bay Area in this period, and they just happened to like playing together, and they just happened to be in at the beginning of a real hip scene . . .

The book inserts context through a series of insertions of real dialogue, from period interviews and news appearances. Governor Reagan shows up to decry the use of illegal narcotics by the nations youth at the same time the band was busted for pot. The historical context is important. The right wing amplified and distorted the original Haight / Ashbury scene to cosmic proportion and turned the counter culture into the site of a culture war that we’re still fighting today. Of course, it’s also worth noting that there was lots going on in 1967 besides pot busts on the Haight. A very fraught year in the nation’s history is elided almost completely by calling it the Summer of Love. A relatively small amount of kids turning on and tuning out in San Francisco communes for a few months - and that’s really all it was, just an eyeblink before Joan Didion arrived to set the place on fire - seems like small potatoes next to all the cities around the country that burnt during that same “Long Hot Summer.” Funny how stuff sticks different in memory.

But then - wasn’t that the criticism all along? That the massively overpraised canon of 60s rock & roll was never bad per se, so much as just - not the whole picture? If you’re younger than me you might not remember a time when Boomer rock was everywhere. It was the cultural default for a good while whether or not you gave a shit, especially back before they even played black artists on MTV. That was the root of the animus: they stuffed it down our throats for decades, so of course lots of people felt plenty motivated to piss on the canon. How could you ever truly appreciate the Beatles if they were literally all anyone ever fucking talked about . . .

I have an instinctive revulsion towards that particular school of old guard music writing that posits 60s and early 70s rock - and especially stuff with clear and unambiguous debts to folk and/or blues Americana - to be the only real rock, with everything else essentially fanfic and kiddy stuff. It’s why Jann Wenner held the line at the Hall of Fame against popular synthpop acts for decades, but since Depeche Mode finally made it (only this year, fifteen years after eligibility) I guess I have to retire that particular grinding axe. I like Bob Dylan as much as the next not-guy, but you have to respect the fact that he figured out real early that rich white hipsters went nuts for faux rootsy cornpone shit with titles like “Old Roy’s Goodtime Jugband Malaise Switcheroo.” He rode that grift all the way to a motherfucking Nobel Prize, game recognize game.

Now, the funny part is . . . much as I hate to admit it, the Dead were ahead of their time. I mean, they did all the stuff back then you’re supposed to do now: they had branding, logos, mascots, merchandise, a whole touring empire that somehow managed to remain accommodating to the core of the fans who built it from the ground up. No wonder they stuck around, of course. And it’s also no wonder they didn’t fare so well during a period where every rock & roller laid up nights worrying about the perils of “selling out.” The Dead never really “sold out” in those terms because they never really switched up what they were doing in the first place, just adjusted for scale. They sold bumper stickers because the fans wanted bumper stickers.

It’s a different world. I spend all day every day hustling just for the chance to sell out. Things like fandom matter now. Rock bands since the Beatles have often practiced a passive aggressive relationship with audiences, clearly needing the fame and attention to survive but also hating the actual consequence of said fame and attention. To be fair the Dead never seemed to struggle with the concept of being good to fans: from the very beginning the group, or at least in Miskiewicz and Van Sciver’s telling, are highly responsive to their fans, playing for the most eager and enthusiastic in the crowd and trusting their enthusiasm to sell the concept to the rest of the audience. What do you know, that actually kind of works - give the fans what they want and let them be part of the experience.

All of which leads us to 2020 and the book we’re still ostensibly discussing: Grateful Dead Origins. It’s a multimedia tie-in to a blockbuster entertainment sensation, certainly, but it’s also clearly been made by fans for an audience of fans. There’s a love for the band on display that I find I cannot completely shake, much as I may dislike the music itself. In the Introduction David Lemieux states that “most of the stories, the main signposts of the Dead’s early years, are well known, but the characters and vibe are largely secondary, with the overall importance of an event or experience being the main gist of the Dead’s early history.” These are familiar tails to people, old chestnuts lovingly and uncritically displayed. For an outsider it’s a bit like watching an unfamiliar performance of the Stations of the Cross - it may look pretty but boy is it missing something if you’re not already 110% “on the bus.”

All of which leads us to 2020 and the book we’re still ostensibly discussing: Grateful Dead Origins. It’s a multimedia tie-in to a blockbuster entertainment sensation, certainly, but it’s also clearly been made by fans for an audience of fans. There’s a love for the band on display that I find I cannot completely shake, much as I may dislike the music itself. In the Introduction David Lemieux states that “most of the stories, the main signposts of the Dead’s early years, are well known, but the characters and vibe are largely secondary, with the overall importance of an event or experience being the main gist of the Dead’s early history.” These are familiar tails to people, old chestnuts lovingly and uncritically displayed. For an outsider it’s a bit like watching an unfamiliar performance of the Stations of the Cross - it may look pretty but boy is it missing something if you’re not already 110% “on the bus.”

The book will find a happy home on many fans’ shelves. As far as ancillary media tie-ins go, it’s clearly been put together with care and respect for its audience. That’s the name of the game now, after all, and I can’t say it isn’t an improvement even if I miss the good old days when we could still judge each other mercilessly for our terrible tastes. Born too late, alas.

Does the book work completely? No - as I alluded earlier, the attempts at illustrating performance fall flat for me. Probably not a surprise since I don’t know any of the songs they’re performing. Not a blessed one! Lyrical passages like “Sleepy alligator in the noonday sun / sleeping by the river just like he usually done / he call for his whisky, call for his tea / call all he want but he can’t call me” could have great significance and pith, but in context to a disinterested reader play little different than, say, “The Krypton Crawl.” Given that, in terms of whether or not this book holds any appeal or interest to anyone who doesn’t already have a favorite Dick Pick, the only real answer is, “does it matter?” It’s clearly not for me or people like me. It doesn’t work completely as a comic book because it’s not supposed to be encountered in a vacuum apart from the music.

(And wow, is that an unfortunate name for your archives series or what? I know it dates to 1972 but that’s just a great, great example of parallel evolution at work. Just had to point that out since I probably won’t be near these parts again.)

The Grateful Dead remain one of the most popular entertainment phenomena in history. They are not hurt one bit by the flinging of my rude brickbats. Incidentally, for those that care about such things, there’s a QR code at the beginning of the book with links to some music. I don’t know what, as my reaction upon encountering the caption “scan the code to listen to some Grateful Dead music” was a prompt “Not today, Satan!” But then on further reflection I think I got it wrong, because everyone knows the only music they play over the PA in Hell is Phish.