Artist Sylvia Nickerson lives in Hamilton, Ontario, a large rustbelt city that has been in decline for several decades. But Hamilton, “known as the armpit of Ontario, owning to its industrial smells,” is now at a crossroads, its old guard clashing with the new. As in many other North American cities, gentrification is happening at an accelerated rate, with developers transforming formerly rundown neighborhoods into luxury condos and high-rent apartment buildings, chic boutiques and restaurants. This process displaces the median-to-low-income working class, often including artists, who scramble to find affordable alternatives.

Creation works as a sort of séance for the city, calling up the specters of its past in order to understand better its present difficulties and uncertain future. Throughout, Nickerson notes how the city’s changing nature both reflects and reverberates in her own life, and how that enables her to connect to a larger community. It’s a story of gentrification but also regeneration. Nickerson artfully and movingly makes the personal universal and vice versa.

The book’s opening chapter is called Crucible, a word literally defined as “a situation of severe trial, or in which different elements interact, leading to the creation of something new.” Creation grapples with that very situation, presenting its many facets. Nickerson’s narrative is non-linear, crosscutting back and forth in time, in her telling of both her personal life and of the neighborhoods and streets of Hamilton. A “crucible” is also defined as a metal container, and Nickerson repeatedly evokes the imagery of a container with the cityscape of Hamilton rising up or spilling forth.

Nickerson also examines uncomfortable intersections of privilege and class. We see her as a young artist, moving into a cheap studio space on James Street in a downtrodden neighborhood. Eventually, as more artists move into the neighborhood, it acquires a certain cachet and property values rise. But there is pushback: prior to a trendy art-crawl event, activists place leaflets in galleries stating that what the neighborhood really needs are women’s shelters and needle exchanges, “not art galleries, art supply stores, and restaurants.” Another flyer is even more blunt: “Get the Fat Cats off James Street.” The artists, in turn, feel attacked: “They’ve invested in the neighborhood, and feel they belong as much as anyone else.” But Nickerson painfully acknowledges her complicity: “Our presence has displaced people.”

Later in the book, Nickerson shows us James Street today, filled with chic boutiques that have replaced the art studios, including hers, illustrating the relentless food chain of gentrification: there is always a higher-income populace waiting to replace the present one.

In one episode, Nickerson recalls once buying food for a homeless woman named Nancy Shepard, who has recently been found murdered on the street. Nancy becomes a symbol of the collateral damage of the city’s most vulnerable citizens. After a public memorial for Nancy, people say all the nice things (“So sad” … “So touching”) and then move on to their lives (“I need a snack” … “Tell that reporter to get lost”). In lovely, elegiac imagery, Nickerson depicts Nancy joining the other ghosts of Hamilton, drifting on clouds above the neighborhoods and skyscrapers, becoming another part of Hamilton’s infinite number of memories. In this way, Nickerson presents the city as a living organism, made up of countless histories and constantly evolving as the past is swallowed up in the present. She carefully recreates the graffiti, flyers, and posters that dot the streets and buildings of Hamilton, which we come to see as a sort of communal dialogue.

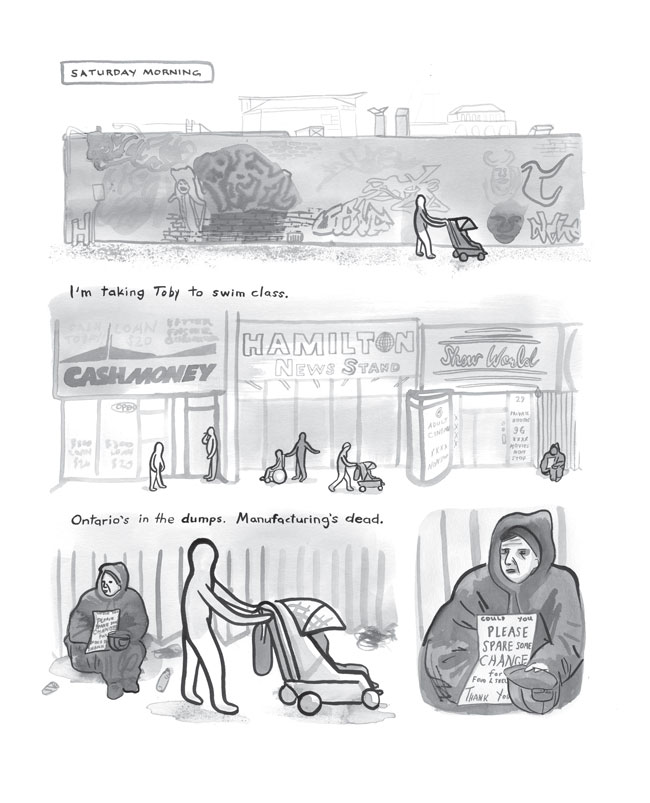

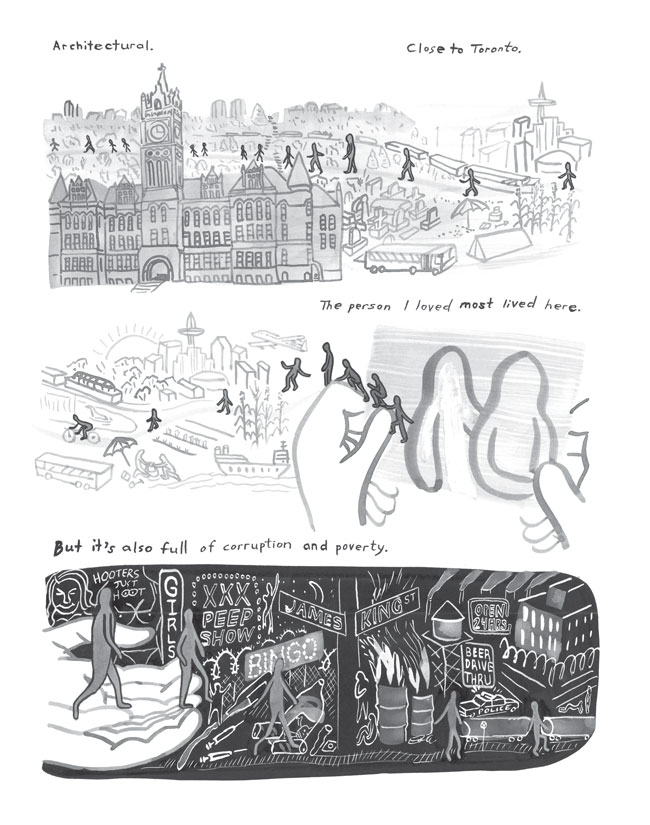

As Hamilton struggles with its identity so, too, does Nickerson. In a flashback to her teen years she confesses, “I made the world still centred around me. That’s how I felt when I was first pregnant. But that’s also when it became clear that things were about to change.” After her son is born, she frets about how this will impact her career as an artist: “I’ve turned into a baby cooing, babbling, brainless, child-centric bore.” Meanwhile, her parents both become diagnosed with cancer and begin chemotherapy. The deterioration of their health as her boy grows up continues Nickerson’s themes of decline and regeneration. She draws herself as a little anonymous figure, wheeling her son along city streets, surrounded by panhandling homeless people and graffiti-scribbled walls. She depicts the citizens of Hamilton as Keith Haring-like characters roving about; it is only when she shows them in closeup that their features come into focus. We get the sense that Nickerson is acknowledging that while we never truly know the scores of people we pass on city streets, everyone contributes to the lifeblood of the community, creating a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Nickerson’s drawings are simultaneously detailed and expansive. Many pages of Creation are devoted to her gorgeous, ink-washed cityscapes, which vividly capture the bleak poetry of rundown neighborhoods with their broken windows and ruined chain-link fences, contrasted with the huge steel and glass skyscrapers of its downtown area. She closes out the book with a series of these cityscapes, jumbled with clouds and ghostly figures floating above, and repetition of the words “It Begins” drifting past “The End” and “Forever” floating next to “I’m Sorry.” The power of Nickerson’s work derives not from heavy-handed didactics but her velvet-glove, poetic approach to complicated yet universal, timeless issues. Creation is a soulful, big-hearted work of depth and vision.