Tetsunori Tawaraya sings and plays guitar in the Japanese noise-punk duo 2UP, and his previous band supported The Slits for a few dates of a US tour during that outfit's final Viv Albertine-less period. So if you're the kind of comics reader who appreciates some complementary mood music, it's not hard to make a stab at the kind of playlist Tawaraya might have in mind for the perusal of Assassin Child.

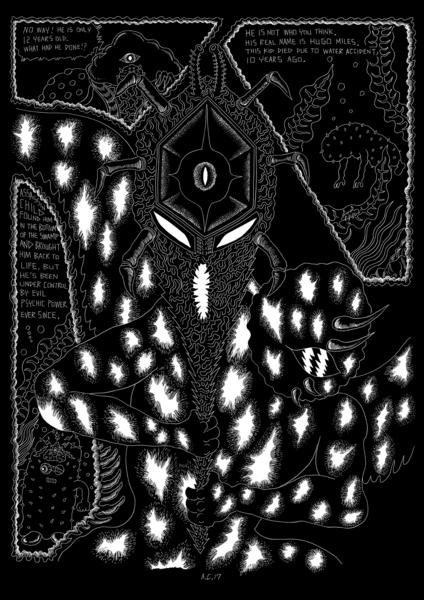

The Italian publisher Hollow Press under Michele Nitri has been bringing Tawaraya works to Western readers since 2016, and before that included him in its U.D.W.F.G. anthology title alongside artists such as Mat Brinkman and Ratigher, a pointer to Tawaraya's artistic direction of travel. Assassin Child is his latest one-shot creation, and manifests in the same particular physical form as its Hollow Press predecessors, with the art created on black scratchboard and then printed as silver ink on black coated-PVC paper. Eye-catching enough at the fairly conventional 24x17 cm dimensions of the previous books, Assassin Child has been scaled up to 34x24 cm, not far short of Marvel's old Treasury Edition size. The artist hasn't noticeably adjusted the art style for the changed dimensions; but since that style is all about meticulous semi-obsessive mark-making that spills out across the available real estate with a high percentage of full-page spreads, perhaps the format has adapted to meet the art.

Assassin Child has a very broad storyline, a wide-eyed genre riff whose internal logic sometimes doesn't survive the turning of a page. A spacecraft piloted by an alien being with a proboscis vaguely like those Space Jockeys that HR Giger whipped up for Alien crash-lands on a planet called Gwun, whereupon he turns out to have been carrying a nasty sentient brain parasite from a species known as Assassin Child. Two pages and 200 years later, a host of cloned Assassin Child(s) are installed in the heads of an army of zombiefied Gwun inhabitants, and fighting a war against un-infected civilians. The bad guys are nearing completion of a doomsday device, a humanoid whatsit referred to as both Toxic Emperor and Bad Blood, while the planet's resident deity, accurately called the Gnarly Dragon, is working on a master plan. There's also an imp riding a skeletal Richard Corben/Meat Loaf motorcycle, alien juveniles blithely going about a school project, and an outer-space hitch-hiker being picked up in a space-going automobile driven by something that resembles Immortan Joe in Mad Max: Fury Road, if you squint a bit.

So the story is a freestyle improv that probably benefits from the sense that Tawaraya is fitting the English language dialogue around the visuals with a healthy margin for error, and the art is built from meticulous work with the scratch knife that suggests the steadiest of hands. The silver-on-black lines turn Assassin Child into a celestial bestiary, an inexplicable zodiac of tentacled fauna and insectoid critters, their relationships and place in the food chain left largely for you to intuit. Although Tawaraya mostly does without backgrounds and allows the black paper to create the scratchboard equivalent of negative space, he also fills the foreground plane with lines of force, filigree constructions, and some shimmering lexicography. Painstaking primitivism.

So the story is a freestyle improv that probably benefits from the sense that Tawaraya is fitting the English language dialogue around the visuals with a healthy margin for error, and the art is built from meticulous work with the scratch knife that suggests the steadiest of hands. The silver-on-black lines turn Assassin Child into a celestial bestiary, an inexplicable zodiac of tentacled fauna and insectoid critters, their relationships and place in the food chain left largely for you to intuit. Although Tawaraya mostly does without backgrounds and allows the black paper to create the scratchboard equivalent of negative space, he also fills the foreground plane with lines of force, filigree constructions, and some shimmering lexicography. Painstaking primitivism.

Hollow Press previously published Tetsupendium Tawarapedia, a 400-page A5-size selection of the artist's stories from 2002 to 2012, none of which look like Assassin Child but do reveal a few markers on the road towards it. These narratives (William Burroughs-style cut-ups, more accurately) are also always crunching gears, sliding from one briefly established set-up to the next, with creatures morphing and splitting open to reveal different organisms within. There's charm in the book's simpler work, drawn in Tarawaya's scratchiest black strokes and outlines, but things feel like they kick off properly when he starts using thick lines and something closer to underground cartooning for the same kinds of stories; and then shifts again towards a sinuous fine-lined filigree style, with the black scratchboard work clearly approaching in the future. (Tawaraya also works with four-color Risograph printing, which isn't in this book or the current Hollow Press range.) The Tawarapedia has a cover quote from Mat Brinkman calling it "mutant nightmare comics," and some of the individual images might fit the bill—the one apparently called "Centipede Nightmare Dr Benway's Portrait" waves the Burroughs flag again. But a lot of the stories are more along the lines of scatological jokes. Unhappy characters take drastic steps to relieve constipation or stop vomiting or fix their diseases. One is clearly crumbling under some form of post-traumatic stress. Another, at the end of a story that otherwise has nothing to do with him, walks into a medical device intended to cure him of some unspecified tumor-related unpleasantness and emerges transformed into Midnight Cowboy's Ratso Rizzo for his trouble. So it goes.

Hollow Press previously published Tetsupendium Tawarapedia, a 400-page A5-size selection of the artist's stories from 2002 to 2012, none of which look like Assassin Child but do reveal a few markers on the road towards it. These narratives (William Burroughs-style cut-ups, more accurately) are also always crunching gears, sliding from one briefly established set-up to the next, with creatures morphing and splitting open to reveal different organisms within. There's charm in the book's simpler work, drawn in Tarawaya's scratchiest black strokes and outlines, but things feel like they kick off properly when he starts using thick lines and something closer to underground cartooning for the same kinds of stories; and then shifts again towards a sinuous fine-lined filigree style, with the black scratchboard work clearly approaching in the future. (Tawaraya also works with four-color Risograph printing, which isn't in this book or the current Hollow Press range.) The Tawarapedia has a cover quote from Mat Brinkman calling it "mutant nightmare comics," and some of the individual images might fit the bill—the one apparently called "Centipede Nightmare Dr Benway's Portrait" waves the Burroughs flag again. But a lot of the stories are more along the lines of scatological jokes. Unhappy characters take drastic steps to relieve constipation or stop vomiting or fix their diseases. One is clearly crumbling under some form of post-traumatic stress. Another, at the end of a story that otherwise has nothing to do with him, walks into a medical device intended to cure him of some unspecified tumor-related unpleasantness and emerges transformed into Midnight Cowboy's Ratso Rizzo for his trouble. So it goes.

Assassin Child feels like a children's story that some of those creatures might tell each other, a thunderous foundation myth about their own crazy cosmology. The plot is only there as a surface for Tawaraya to scratch his art onto, and if that art isn't as visceral (or venereal) as some of the stuff in the Tawarapedia, then the artisanal mechanics of its creation manage to make it both more dense and more delicate instead. It would be hard to call Assassin Child noise-punk, much less outlaw; but it's not without rebellion, a visually rippling push-back against rigid obedience. The amorphous figures and presumptuous faces are always metastasizing, always pretending to be something else and then sloughing off the disguise. In Tawaraya's comics, everything has the ability to become something else, and is probably about to do so.

Assassin Child feels like a children's story that some of those creatures might tell each other, a thunderous foundation myth about their own crazy cosmology. The plot is only there as a surface for Tawaraya to scratch his art onto, and if that art isn't as visceral (or venereal) as some of the stuff in the Tawarapedia, then the artisanal mechanics of its creation manage to make it both more dense and more delicate instead. It would be hard to call Assassin Child noise-punk, much less outlaw; but it's not without rebellion, a visually rippling push-back against rigid obedience. The amorphous figures and presumptuous faces are always metastasizing, always pretending to be something else and then sloughing off the disguise. In Tawaraya's comics, everything has the ability to become something else, and is probably about to do so.