If Gillo Pontecorvo’s insurgency instruction manual, The Battle of Algiers, encompasses your knowledge about 20th century Algerian history, then congratulations, that pricey three disc Criterion edition was worth it. As for those remaining non-Algerian, non-French and their non-Criterion watching corresponding adjacencies … Algeria, ummmmm …

Writer, Olivia Burton, and illustrator, Mahi Grand, of Algeria is Beautiful like America, choose not to pursue Pontecorvo’s approach to fan the sparks of rebellion into the flames of revolution. No, for them the fire is cozier and contained, like to a fireplace in the well-appointed environs of a living room, where a family’s history, secrets and prejudices are as close by as a fresh pack of Gauloises or a plate of pastel-colored macaroons.

Algeria is Beautiful like America is autobio comics at their autobio-i-est, with Olivia (she omits her surname throughout the narrative) on a hyper-personal existential quest to interrogate her family’s Algerian past for herself. The word ‘Algeria’ in the title is arguably circumstantial to the text itself (ditto for the word ‘America,’ more on that later). Yes, this is a story about a white French women of some means searching for her family history -- specifically on her maternal grandmother’s side -- in an African country, so yes, Algeria is important to the story, however; what Olivia craves is the one treasure left in our current culture, authenticity. She doesn’t want memories or recollections. She wants to put her finger in the holes left by the nails; she wants the facts, the truth—nowadays that’s as seditious and rebellious as it gets.

While Olivia does the work to unfold her past, she can only go as far as her arms can reach or her itinerary takes her. Issues of immigration, colonialism, xenophobia, social and religious tolerance are all filtered through her lens. She provides snapshots, misses the bigger picture and leaves it for the reader to piece it all together.

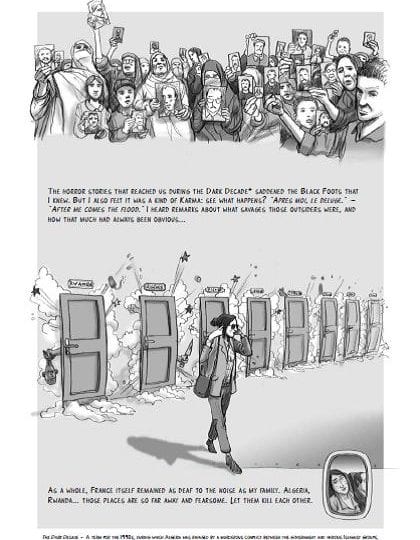

One exception of Olivia's ownership of her willful ignorance comes early on in a single page depicting the ‘Dark Decade,’ which she footnotes as “a term for the 1990s, during which Algeria was ravaged by a murderous conflict between the government and various Islamic groups.” Grand illustrates Olivia holding her fingers in her ears, her mouth closed and wearing sunglasses (deaf, dumb and blind) as she walks with her back to a line of closed doors roiling with violence. Nameplates over the doors read ‘Algeria,’ ‘Bosnia’ and ‘Rwanda."

One exception of Olivia's ownership of her willful ignorance comes early on in a single page depicting the ‘Dark Decade,’ which she footnotes as “a term for the 1990s, during which Algeria was ravaged by a murderous conflict between the government and various Islamic groups.” Grand illustrates Olivia holding her fingers in her ears, her mouth closed and wearing sunglasses (deaf, dumb and blind) as she walks with her back to a line of closed doors roiling with violence. Nameplates over the doors read ‘Algeria,’ ‘Bosnia’ and ‘Rwanda."

Yes, there are takeaway messages and life lessons to be gleaned from Olivia’s Algerian travelogue, and there’s also a big bolus of 19th and 20th century Algerian and personal family history to chew and digest. In brief, Olivia’s grandparents were Pied-Noir (or "Black Foot") an Arabic term (translated into French) for the children of French emigres who came to Algeria during French rule from 1830 to 1962 and returned to France when Algeria gained its independence. Burton (the author) tries to keep all this French/Algerian history to the first of the book’s seven chapters, but because it’s central to the project it's parceled out on a need to know basis.

This is the first major work for both Burton and Grand. Due to the book’s tripartite structure of history lesson, travelogue and memoir, Grand does yeomen’s work compressing large chunks of history into a few pages or a few images and making the places Burton visits look, well, real. He uses color sparingly and exclusively within the frame of the photos Olivia takes on her trip. This use of color symbolizes the future, as she sees it; the colored photographs allow Olivia to tell a new story and create new memories separate from her family’s history. Grand renders the rest of the art in black and white, which allows him to conflate the past and present into a kind of present-tense of appropriated nostalgia. It’s a smart approach to visual storytelling and it’s what makes Algeria is Beautiful like America a comic rather than an illustrated travelogue.

As much as Olivia’s story is a reckoning of her family’s history, it is also a pilgrim’s story. As such, it gains traction when it finds its Virgil in Djaffar, the brother of a friend of Olivia’s mother and an ex-Pat Algerian Muslim who happens to be working in Algeria during Olivia’s visit. He agrees to guide her through “this stony desert,” to the region around the Aurès Mountains where Olivia's family once lived. Djaffar’s presence is what (literally and figuratively) drives the narrative forward and takes Olivia’s story from a solipsistic slog to something approaching a larger worldview. Djaffar’s pragmatism balances Olivia’s dreaminess and naiveté. He’s a sidekick, which means he gets all the best lines, like when he speaks truth to her idealistic notions and familial obligation: “the only things that mattered back then were political positions. But that’s over now. No one in France today defines themselves by saying, ‘I’m the son of a collaborator!’ That’s not an identity. Same goes for ‘child of a Black Foot … it means nothing.” Olivia is haunted by the past....Djaffar, not so much. He's the voice of the "can't-you-move-on-and-just-get-over-it" crowd, but engaged, patient and (above all) active. Later, he tells Olivia about his experiences growing Muslim and his family’s involvement in the Algerian War which makes her guilt of being a ‘child of a Black Foot’ raised by a loving family in France pale in comparison.

The parallel between Djaffar and Virgil in the Divine Comedy is not made lightly. It’s an acknowledgement of Burton’s shrewdness for seeing how her narrative-self falls short in bringing her personal story and European sensibilities into a non-European culture. First-person narration is the grist that grinds the grain of autobio comics, but the addition of Djaffar allows Burton, like Dante with Virgil in La commedia, to comment on the actions, foibles and ignorance of the protagonist. This pilgrim-protector point-of-view provides Algeria is Beautiful like America with the perspective it otherwise would lack. Virgil is, first and foremost a guide and protector, but he also gets to dog Dante for his shortsightedness, and Djaffar does likewise for Olivia, saving the reader from her constant navel-gazing.

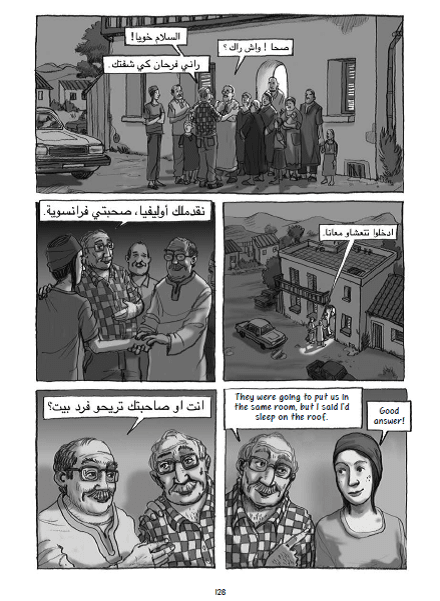

Unfortunately, the good will and representation Burton gains from Djaffar is quickly diluted when he and Olivia encounter Arabic speakers, which they do, a lot. Burton chooses not to translate any dialogue spoken in Arabic, including when Djaffar speaks in Arabic. This choice is, at best, problematic and at worst, intolerable. As much as it gives Olivia a ‘fish out of water’ point of view, it reads as culturally ignorant and insulting to the reader regardless of their native language. What makes it worse is every Arabic speaker Burton and Djaffar encounter are kind, welcoming and go out of their way to help. Why leave their dialogue untranslated? Thankfully, this is a comic from a boutique publisher “with a strong focus on culturally diverse creators and stories” written by a French women, so no one need worry.

Unfortunately, the good will and representation Burton gains from Djaffar is quickly diluted when he and Olivia encounter Arabic speakers, which they do, a lot. Burton chooses not to translate any dialogue spoken in Arabic, including when Djaffar speaks in Arabic. This choice is, at best, problematic and at worst, intolerable. As much as it gives Olivia a ‘fish out of water’ point of view, it reads as culturally ignorant and insulting to the reader regardless of their native language. What makes it worse is every Arabic speaker Burton and Djaffar encounter are kind, welcoming and go out of their way to help. Why leave their dialogue untranslated? Thankfully, this is a comic from a boutique publisher “with a strong focus on culturally diverse creators and stories” written by a French women, so no one need worry.

And about that use of ‘America’ in the title? With the exception of the title and a couple of instances where the word ‘American’ is used (once to describe a "North American Indian" tribe, the Blackfoot) there is only one use of the word ‘America’ in the story. When Olivia returns to Paris and shares her journey with her mother over a glass of wine, she tells her the highway to the Aurès looks like “the American West.” Her mother corrects her, “No,” she says, “it’s even more beautiful than America.” Since when did Olivia's mom 'go West?' Burton gives no indication prior to this denouement of her mother's fondness for America or 'the West.' Why not Australia and the Australian outback or Albania and the Albanian coast? Or another of the seven countries that begin with the letter ‘A’? Like the untranslated Arabic it’s an odd choice that confuses more than enlightens.

In the end, Olivia accepts her family once stood on the wrong side of history. You can almost here the 'Kumbayas' as she rides the Paris Métro and notices how her fellow travelers, regardless of color or creed, are human beings ... just ... like ... her. Vive la Oliva! Although appropriate and authentic to the story, this 'good for her' notion falls flat. Where's the struggle? A few of pictures of her travels and a glass of wine with Mom late and all's well that ends well?

Burton owns her damage: commendable. But like some self-help life coach she wants the reader to believe ... like her ... that such self-knowledge can be achieved in a charming and fairly non-confrontational manner, at least it did ... for her. The rest of us will have to come up with a nonsensical snappy simile on our own.