The stories that populate A Western World, a collection of Michael DeForge’s recent short comics, make for troubled residents, concerned with the mutability of bodies, the relationship between body and self, and how technology affects intimacy—some of the same notions found throughout DeForge’s larger body of work. Readers fond of DeForge but new to these pieces won’t find major departures in the book, but that’s only one measure of the collection and perhaps not the best one. DeForge has long since found his themes and a sensibility with which to approach them. The pleasure of A Western World is the pleasure of seeing him return to these concerns from new angles.

The collection is a book of gradients, of pieces about bodies and societies rendered with different hues, in different keys, through different lenses. Within a sort of prevailing aesthetic (flat colors, limited hatching, figures and backdrops made of a few defining shapes), DeForge adopts a range of styles throughout the collection and manages to adjust his approach from story to story while remaining recognizably himself. For converts, the appeal here may be in the details, the minor changes, in addition to what concerns of theirs they find reflected. For newer readers, the book makes a fine introduction to a cartoonist who expertly blends form and subject.

Throughout A Western World, bodies—and what one’s body says about one’s self—are always subject to change. In “Adults,” a child distorts herself into a more adult-like shape, then dominates the friend who egged her on. In “Margot Airplane,” a trust-fund kid surgically alters her body so she can fly through the air. Two pieces, “About Kissing” and “Boy,” envision separate species merging to produce new, distinct beings. One of the collection’s simplest pieces, “Quicksand,” is one of the most effective in exploring life (and in this case, death) in human skin.

“Quicksand” follows a man trapped in muck as creatures outside his view bite or otherwise assault his person. He tries to feel out the source of each sensation, mistaking, for instance, a snake for a vine. DeForge’s panels alternate between the man himself, speaking to some prospective rescuer, and glimpses of his tiny assailants. By the comic’s end, the man’s thoughts take an existential turn: “I can’t see my body/Or touch my body with another part of my body/So maybe I don’t have a body at all.” It’s a darkly funny piece that questions the difference between what we feel and who we are.

Sex features in many of these stories, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly. “It has always been my fantasy to have several dozen tiny people enter my body while I soar above the ground,” says the title character of “Margot Airplane.” This too is a comedic beat, but also an instance of a character changing her body in order to change how others interact with it. Meanwhile, in “About Kissing,” the merging of species takes place as one creature (in briefest terms, a walking mouth) approaches and then consumes the other creature (a walking asshole). This is once again an absurd moment but a more sinister one, with one party the apparent aggressor.

Even when sex is consensual in DeForge’s work, his characters often don’t seem to enjoy it. His work is not sex negative, but its depictions of sex sometimes suggest a wider ambivalence about people finding lasting connections or satisfaction. The comics seem to recognize sex as a part of the human experience in which people try and sometimes fail to make interpersonal breakthroughs, and DeForge (here, and also in longer works like Big Kids) can frame the act as a disappointing, alienating thing.

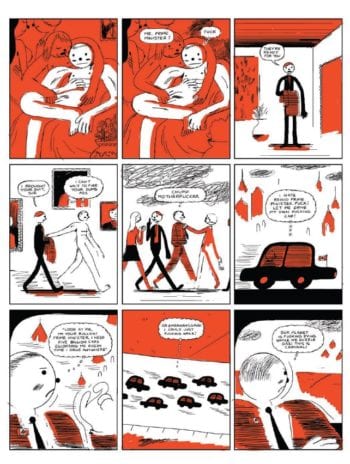

“The Prime Minister of Canada” begins in this space, with an unnamed politician lit by the glow of a television set, facing away from the other members of an orgy. “Prime Minister” is one of the collection’s lighter pieces, though with DeForge, that’s relative. Readers learn that the prime minister’s discontent is comprehensive. He travels from appointment to appointment, nursing resentments in his thought balloons, all of which DeForge renders in a red, white, and black palette and unusually loose, scratchy linework that suits the P.M.’s agitated bent.

“The Prime Minister of Canada” begins in this space, with an unnamed politician lit by the glow of a television set, facing away from the other members of an orgy. “Prime Minister” is one of the collection’s lighter pieces, though with DeForge, that’s relative. Readers learn that the prime minister’s discontent is comprehensive. He travels from appointment to appointment, nursing resentments in his thought balloons, all of which DeForge renders in a red, white, and black palette and unusually loose, scratchy linework that suits the P.M.’s agitated bent.

DeForge uses a lively voice for his subject in “Prime Minister,” not just dissatisfied but childish too: “I can’t wait to fire your dumb ass/Chump motherfucker/I hate being Prime Minister. Fuck!” Elsewhere—in the Western collection, and in books like First Year Healthy—the delivery of DeForge’s narrators is more matter of fact or even affectless. This is presumably all by design—and consistent with the comics’ alienated POV—but the real artistic flourishes in A Western World tend to take place via DeForge’s linework and compositions. “All Dogs Are Dogs,” the collection’s one instance of pure prose writing, overstays it welcome at four pages. It’s not a painful piece of work, but it’s an entry removed from the techniques that make DeForge’s comics most compelling.

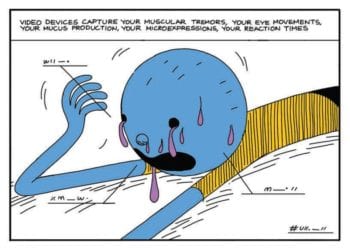

“Dogs”—which outlines the tensions between regular and “advanced” canines—is one of several pieces preoccupied with technology and the ways in which it further complicates characters’ interactions. “Computer,” originally found in Kramers Ergot 9, is set in an online space made physical (and weirdly pastoral). A humanoid guide stands among plants and insects and reminds a user, Roger, to check his emails before they “shrivel up and die.” The guide and Roger later exchange oral sex, and in the comic’s treatment of the act, it becomes something both unremarkable and alien. Another comic, “Grief Analytics,” describes a digital surveillance program designed to record people crying, with companies gathering data “to help interpret and predict your moods, diet, routines, etc.” In both pieces, the intersection of technology and human experience appears to dehumanize that experience—which sounds obvious, but the comics succeed in making the loss resonate. In “Grief,” DeForge’s pages are especially barbed: “Your heart rate and lung capacity are tracked,” one caption reads. “Your individual tears-per-minute (I.T.P.M.) number is calculated.

DeForge isn’t typically positioned as a creator of speculative fiction, possibly because his work emphasizes the personal impacts of his imagined technologies, but these pieces have in common with some of the genre’s best works a humane ethic and a sharp sense of irony. The larger collection functions in a similar way. With its stories taken together, A Western World conveys a worldview, configuring DeForge’s comics into an argument about what’s broken and what’s still at stake. A sense of connectedness, a sense of self, hope for the future—they can be hard to come by under any circumstances, and most environments don’t make the effort easier. As surreal as these comics are, they’re realistic about disappointment. But there are comforts in the works too—reminders of a whole population of people still trying.

DeForge isn’t typically positioned as a creator of speculative fiction, possibly because his work emphasizes the personal impacts of his imagined technologies, but these pieces have in common with some of the genre’s best works a humane ethic and a sharp sense of irony. The larger collection functions in a similar way. With its stories taken together, A Western World conveys a worldview, configuring DeForge’s comics into an argument about what’s broken and what’s still at stake. A sense of connectedness, a sense of self, hope for the future—they can be hard to come by under any circumstances, and most environments don’t make the effort easier. As surreal as these comics are, they’re realistic about disappointment. But there are comforts in the works too—reminders of a whole population of people still trying.