Kevin Huizenga’s The River at Night, the recent collection of his Ganges series, is an achievement. It’s the culmination of years of work, the best book by one of our best cartoonists.

Kevin Huizenga’s The River at Night, the recent collection of his Ganges series, is an achievement. It’s the culmination of years of work, the best book by one of our best cartoonists.

In one of his recent notebooks, Huizenga reminded himself not to be “reticent or enigmatic” in interviews. In this conversation, he was neither. We spoke about The River at Night, about process, and about notetaking - first over email, and then in person. - Andrew White

Andrew White: Broadly, are you interested in participating in a critical conversation about your own book? Do you enjoy answering questions about what the book 'means' or about your intentions in certain parts of the story?

Andrew White: Broadly, are you interested in participating in a critical conversation about your own book? Do you enjoy answering questions about what the book 'means' or about your intentions in certain parts of the story?

Kevin Huizenga: I don't enjoy answering the questions, no, but I don't know if that's just because I don't enjoy most things. I don't want to ruin the book. I'm sensitive to the thing where you meet someone and it colors the work. I remember watching a movie, liking it all right, and then watching an interview with the director after and thinking, "oh, that's a shame, this guy is a goofball." After reading your zine, I was happy to know that a lot of what I put in the comics wasn't just getting transmitted out into the void, that you were picking up on these choices. I'm as vain as anyone and like attention, and probably wouldn't be able to stop myself, but in general, I'd just as soon leave it, for the most part...So! Let's get into it!

Tell me about the process of making the zine [All There Is, Andrew’s zine about The River at Night recently republished on TCJ]. How long did it take? What was difficult? What was easy?

When I started working on the zine, I reread the whole Ganges series, most of your earlier work, and several interviews. I kept notes in a sketchbook for a few months and the final version came together really quickly. I think I drew it over a few weeks. I knew from the beginning that I wanted separate sections on different topics. The process felt very natural. There were even a few sections that I wrote for the first time as I was penciling the finished pages. I was excited at the time by the small 'tricks' I noticed when rereading Ganges carefully -- repeated panels, etc -- but I think that I'm now happiest with my broader thoughts about the work.

Originally, I think that I wanted to more explicitly imitate your sketchbook/focus page style, with short phrases, diagrams, and thoughts that aren't always fully explained, but that didn't come as naturally to me as the essay style of the finished version.

Did looking at The River at Night so closely have an impact on my work? You didn't ask this, but I'm asking it as I write this. Maybe. I've done a couple projects that required significant research (most unpublished) and your handling of the Hutton sections was sometimes on my mind as I tackled that work. I've also thought a lot about how The River at Night takes a few ideas and formal concepts that are introduced early on, then refracts them endlessly to build up meaning. Looking closely at how you did that might be the biggest lesson I've taken away for my work, and it's definitely a technique I've tried to implement for myself.

You recently published The Riverside Companion #1, a zine of process notes and drawings for The River at Night. You've talked before about a balance between documenting your process and making new work – how do you see that balance today? Is your calculus at all changed because you've completed this big project after many years?

I like putting out booklets, and I have a pile of stuff that I think would be interesting as supplemental material, and I think it would be interesting and satisfying for me to organize and publish some of it. I have at least 3 or so Riverside Companions to publish, maybe more? It's not that I think people are clamoring for it--it's to scratch my own itch, putting some booklets together. I really do want to be done with it and move on, though. I have sunk a lot of time already into this one book, and it's time to move on, so I don't know. It's a waste of time for me to talk about my plans, really--I end up just doing whatever I feel like, and I should know better than to plan or promise anything. I've thought about boxing it all up and sending it to Billy Ireland, or the Wash U. collection, and getting it away from me.

I'm always working on too many things at once, and so progress is slow.

The first Companion focused on your research for the Hutton section of the book. You describe that as a happy period – I assume this was during the larger gap between Ganges 4 and 5. Was it hard to stay on track in this period? What made it pleasurable?

I’m not sure what you mean or mean to imply by asking if it was hard to stay on track? I was trying to find the track. Once I found it, I worked on writing and drawing it.

I suppose one of the things that happened after Ganges 4 was that I worked on the Leon Beyond strips and then the collection of strips, Amazing Facts and Beyond. I wrote and drew strips every other week for the Riverfront Times in St. Louis. Getting a regular paycheck from the paper, as well as the regular rhythm of deadlines, and appearing in the local paper—all that was rewarding and involving and habit-forming enough that it sucked me in, and it seemed like I was being a good cartoonist, doing a real strip printed on real newsprint. In retrospect…I don’t know. I probably should have stuck to making Glenn Ganges work, or tried harder to do both—Leon ended up coming first and dividing my energy between Glenn and Leon was difficult. The way the world was arranged around me I was getting more reinforcement from the Leon Beyond strips, at the time. Putting that Leon book together also took a lot of time and effort, the indexing and all that ridiculousness. And then people didn’t seem to be interested in the book. It was a surprise. We, Dan Zettwoch and I, didn’t turn Leon into something and we were sick of it, and ended it shortly after the collection was done. I’m still proud of that work, and I think people would be surprised about how good it is. But I can see how the density and design of the book is not inviting, and any regular strip inevitably has peaks and valleys, and a lot of mediocre ones, and ultimately it is kind of hard to read altogether. All that said, I think people should check out that material, if they like my comics—some of my weirdest, most interesting work is in that book.

But once I got going on The River at Night material again, the geology research and “the Funeral” story, it was a happy time because I eventually was working every day at the St. Louis University Library, for many hours every day, and that was a joy. The library is a great one to work in—the architecture and layout of it was open and sunny and quiet and private, big enough to walk around and think, large study carrels, I loved it. In general I think that Catholic university libraries, like SLU, have particularly nice libraries. It was also nice how, as I read and looked for visual reference, almost anything I was interested in, I could usually find on the shelves, and so I’d alternate reading and drawing all day, up on the fourth floor, where there were giant windows and a panoramic view of St. Louis and the sky all around. It was great. Being away from the distractions of the Internet was great too—I didn’t have a laptop. I wish it could have lasted forever. Esp. during the summer, the library was largely empty. When school was on it was only really crowded during exams, and then I’d just keep away. For a week or two it was too crowded, all the study carrels, especially “mine,” were full of smelly, coughing undergrads cramming for their exams.

In your last big TCJ interview, you talk about rereading Ganges 1-4 and finding a way forward by subverting or refracting (mirrors!) the ideas in those issues. Do you have other thoughts on this, now that the book is complete?

Not really. It’s a line of thinking that got interrupted by my marriage ending and the move to Minneapolis, and then the four years of teaching. I kept a lot of notes that I still have, and I’d like to eventually turn that material into something, but I did lose one notebook full of some of the most important work during the chaos of moving. I think it probably got thrown out with a bunch of boxes at some point, which was a terrible thing, and when I realized it too much time had passed to get it back. I thought about going out to the landfill, and even made some calls, but they told me it was impossible. That took some of the wind out of my sails as far as all that, the diagrams about formal things, recursion and dialectics and cartooning, mirrors and so forth, that I was working on… Some of that ended up informing the “Hall of Mirrors of Nature” comic.

The next Riverside Companion will probably be about the mirror stuff, notes and sketches.

The book ended up less "meta" than I was thinking it would be at one point, but I think that's for the best. I had some crazy ideas that I pulled back from, like including a pocket with minicomics in them, or reflective paper, Glenn reading a book about himself, things like that.

I actually think that idea come through in the final sections of the book, because you're building on plot points and formal concepts from the first four issues, rather than introducing anything new. It helps the book feel complete and circular in a really nice way. How did you identify what threads to pull on there? I imagine you must have reread the first issue, for example, to decide you could build a story around the 'airport sandwich' line.

That was part of my strategy for ending the book. The only way out I could figure was to get more “meta,” which is my way of saying to carry the ideas through dialectically, to “level up,” the spirals and circles and grids and all that. I definitely re-read everything and made a list of what to carry forward. (Ken Parille helped me with this too—hi, Ken.)

What do you remember about making the Time Traveling strip that appeared in Ganges 1? Did you recognize it as an important strip at the time?

No, I just knew I was doing a magazine size comic that would appear in several languages. I planned on filling it with some short comics, Little Lulu-style, and the idea for that story was a simple thing, thinking about walking and the timeless feeling one gets when walking the same route over and over for years.

But did you recognize that the ideas from that strip -- about circular time, about grids and panels as representations of time -- would be important, or appealing to explore further?

Not really.

Do you think The River at Night gains or loses anything by being in a book, rather than individual issues?

I hope it doesn't lose anything. I know you said in the zine that it was going to be shit as a book…

I did think about it a lot, going back and forth about whether to design it with the covers and inside covers and all that--just design it like the 6 issues together. But when I did that and printed it out and bound it together I didn't like the way it read. I printed the book out over 30 times, in different sizes and configurations, and would read it and sit with it, and what I thought would work didn't always work when I sat down with it. Something like adding the big Kramers one pager at the beginning of the book, changes like that--when I had the idea to do that, and printed it out and read it, it worked. I wouldn't have predicted it, but I liked it a lot, so I kept it.

I didn't think it would be shit as a book! Remember that I was comparing at the time between the reality of the issues and the potential idea of a book. I'm not sure you'd even said yet that you were working on a collection.

I've always found the process you're describing difficult, sitting with a work and deciding what needs to be changed. Time away from a project helps sometimes for me. How did you keep a sense of objectivity when you were on, say the 25th version of the book?

I don’t know. Early in the morning, first thing, sitting down with it and looking at it usually is how I could get into it.

Are Saul Steinberg's ideas about “materials and appetite” still helpful to you? How have your thoughts about that changed over time?

Sure, appetite in the sense of, now I might say, an intention. A clear intention to do something and follow it through. Not necessarily a plan or an idea ahead of time, but a commitment to do a drawing. Or a couple drawings. And having the materials set up and ready to go, the big sheets of paper, plenty of space, plenty of time. It's a simple thing and probably obvious to many artists, but for me, with my attention jumping around and quickfire dissatisfaction with most things, it was a helpful straightforward way to talk about it... I still struggle a lot with being an artist. I didn't grow up with any role models, anybody to watch. The patience, the confidence, the keeping it fun and light, etc. The needing to warm up. It takes 15-45 minutes just to settle down and not want to jump out of my chair. I learned a lot from watching Dan Zettwoch draw, for years, when I was in St. Louis. Also, appetite and materials helped me as a simple diagnostic tool. If something wasn't going right, the first two questions could be how are the materials? then how is your appetite? What do you want to do? I used to say that I didn't want to draw so much as I wanted to sit and listen to music for a few hours. The drawing was a chance to do that. It's really my ideal. I need to get back to that. Nowadays it's podcasts. I like to listen to a podcast and draw at night--draw in the sense of comics drawing, which, a lot of it is production work, not necessarily being creative or adventurous. For a while it was DVD commentaries. I'd get them out of the library, it almost didn't matter the movie, I'd just look to see if there was a commentary, a crap movie was almost better for background chatter. I know Dan Zettwoch watches, or re-watches, whole seasons of TV shows. Sammy Harkham listens to Howard Stern while he works, which works very well too.

I think 'appetite and materials' is such a useful phrase because it can be very high level -- how do you make yourself draw? -- but also very practical, like suggesting that maybe you should leave a page penciled so that you have the appetite to ink it the next day.

Sometimes I think about appetite like hunger -- I don't eat if I'm not hungry, so I shouldn't draw if the appetite doesn't appear. I shouldn't 'eat' to the point of gluttony or I won’t want to eat/draw the next day. But you can definitely synthesize appetite, and sometimes that's necessary. Is that balance difficult for you?

Yes. After all these years I still haven’t figured it out. I sometimes hit on a good rhythm of working and taking care of chores and etc., but it never lasts. There’s always a crisis or some admin to take care of, or a trip, and then getting back to the momentum is difficult. It’s been a long time since I’ve been able to work regularly on anything. Teaching and the start-stop rhythms of the school year and the week also made it very difficult. I don’t know, I’m still trying to figure it out.

Is a daily routine still an import part of your process? What’s your routine like these days?

I don’t have a good routine. Lately I’ve been doing a lot of reading and I take notes on notecards. I’m trying the Zettelkasten system (https://zettelkasten.de).

Huizenga and I continued our conversation in person at SPX. He’d brought along a small sample of the many notebooks he has kept over the years, where he often worked through ideas that would later appear in the Ganges series.

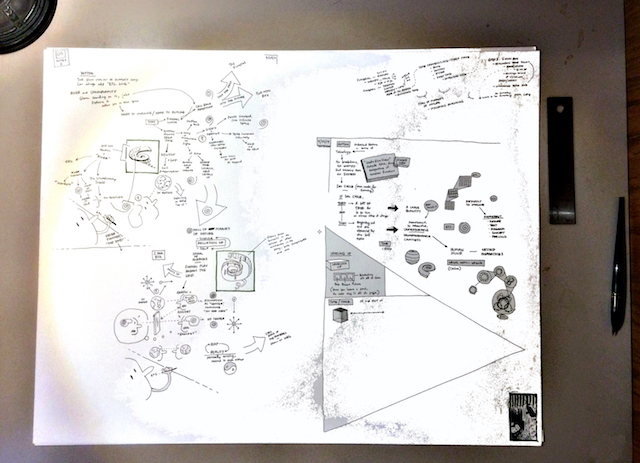

Images from those notebooks appear throughout the rest of the interview, although they aren’t necessarily the specific pages we discussed. This audio transcript has been edited for length and clarity by Huizenga and myself. Our conversation opens as we flip through one of the notebooks, a 8.5” x 5.5” spiral bound volume labeled ‘2013’ on the cover.

Huizenga: This shows the era where I was diagramming and reading a lot of philosophy, but I was also trying to figure out what to do with the Ganges story. I was reading Fredric Jameson's Late Marxism: Adorno, Or, The Persistence of the Dialectic. A lot of the diagramming is about that book, but I also use Glenn [points to images of Glenn, interspersed with notes and diagrams] as my default human being.

Are you thinking about the book at this point, or is this just to help you understand what you're reading?

I'm thinking about the book all the time. I'm doing the reading for fun, but as I'm reading, I'll think about mirrors, and Glenn, and the brain.

I was working on a whole sequence where Glenn would go into this meta realm, and walk around the pages of the book. It was way too crazy, so I ended up not doing it. There are more abandoned ideas like that.

Later, maybe in 2014, I got into figuring out the geology, diagramming about it… [paging through notebook] For a while I was obsessed with the idea that a whole was also represented within the whole. The way that a map could show itself on a map – stuff like that, stuff that could be completely unrelated to Ganges. I'm just thinking about ideas, trying to diagram them.

I've never done anything with this line of work, these pages with stuff about representation, meta-representation, parts and wholes. I never felt like I could make a book out of it. Then my life changed a lot, so I dropped this line of work. But I'll come back to it, maybe, someday.

It seems very related to me, though.

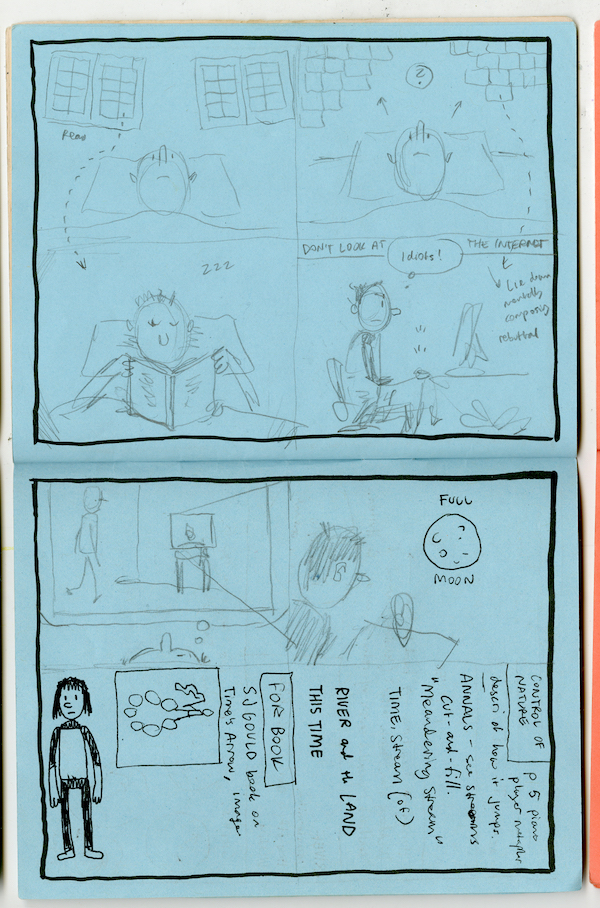

I also have a stack of these [small, quarter-size notebooks of folded paper] specifically about Ganges. I used these as sketchbooks, because they're more casual.

Do you have a system for keeping track of all this? Or does just accumulate over time?

It accumulates. I don't have a system. Lately, I've become convinced by this book that Tom Kacyznski recommended to me, called How to Take Smart Notes. It's about a German sociologist called Nicholas Luhmann. His system, called the slip note system, or zettlekesten in German. He would take numbered notes on notecards. The numbers at times were hierarchical, meaning that notecard 3 could branch off into 3a, and then 3a-1, if the ideas were related.

That book showed me that if you just take notes in notebooks, and you put the notebooks on a shelf, what's the point? It's just dead. The book argued that notecards can be reshuffled, or put in order, and that can turn into an essay. Also by numbering everything you can cross-reference the notes within the system.

I'm probably going to go back through my notebooks and do a combination of putting things in notecards and numbering all the notebooks. For example, I can collect all the notes about mirrors, which is a recurring topic. It seems pretentious and crazy to number your own notebooks, but at point everything is so out of hand with notebooks upon notebooks and pages upon pages.

So with the mirrors, for example, it sounds like you don't think that line of thinking is done just because it appears in The River at Night.

As I was working on the “Hall of Mirrors of Nature” story, I was also reading Richard Rorty's Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature for the first time. I had been interested in pragmatism for a long time but had never read Rorty at all or that book in particular. So I was reading Rorty answering his critics, and I decided to go back and read Mirror of Nature, even though I know from reading later Rorty that he's changed his mind about various things over time.

That book uses mirrors as an extended metaphor for the correspondence theory of truth, and that got me thinking about the mirror as a philosophical metaphor in this particular way that had to do with the brain and epistemology and all that. I’d like to go back and write and draw more about this.

Philosophy books like that are very dense, but your work is never dense in that way. The ideas are there, but the work is pleasurable and smooth to read. So I wonder if it's difficult to condense complex ideas that you've taken pages of notes on into a comic that works well by itself.

I think it's not that difficult to be honest. Those guys are writing specialized language for specialized readers, and it's a specialized conversation. But I'm trying to make a readable comic, but also something that's interesting to me and reflects my concerns and things that are interesting to me. I do end up cutting things, simplifying.

Part of the reason that I'm still stuck on the mirror thing is because I did a lot of drawing, and even pages, that I ended up cutting from the comic, because it was getting a little too crazy. I'm not trying to go too far off the deep end. At the same time that material is still there. I could put in a little more time and work to turn that into a zine.

I would like to make other work that is dense and trippy and difficult. People might say “I like his other stuff, but I'm not into this.” That's fine with me. I want to make different bodies of work.

With Ganges, you've set up a system of rules and I could imagine that not everything you're interested in making work about fits into that framework.

I don't know that it's rules as it is trying to have a sense of taste and balance about when too much is too much. If I do make something that's weird, I try to balance it by making something more approachable.

Your notebooks also seem fairly polished. You're always lettering carefully, you're sometimes using a second color...personally, when I'm taking notes, I'm just trying to get something down on paper as quickly as possible.

I don't think about it in that way. At this point, that's the way that I draw and the way that I write. It's not a choice. It's just the way I do it.

Again, maybe this is just my own approach, but when I'm taking notes I can get impatient because I'm not making finished pages. It seems like you're happy, or comfortable, working in notebooks.

This is the happiest I am, when I'm lost in my head and my notebooks. I'm not in a hurry. I'm just enjoying myself, tracing out lines of thinking.

At the same time, I am conscious of the fact that it's a fragile thing when you're working like this. If you get too caught up in your head and you're trying to make the notes look too good it ruins the flow.

You've talked before about the balance between documenting your process versus just making the work.

I think in the last six, seven years there's definitely an imbalance. I found myself filling up notebooks but not drawing pages. Earlier I saw a lot of cartoonists who worked in their sketchbooks all the time and never made pages, and I didn’t want that to be me. I made a conscious effort, that if I drew, it was going to be on a comics page for publication.

But that shifted at some point. I was drawing in notebooks more and more, and not publishing it. It became notes about philosophy books or something else that I can't just publish as-is.

Are you okay with that?

No, I'm not. I want to shift back to drawing comics pages instead of scribbling notes and diagrams.

In the old days I'd sit down and write scripts. Not full scripts, but I might write “Glenn Ganges is walking to the store. He sees an umbrella in the gutter. As he goes to pick it up...” I need to shift back to where I'm writing short vignettes and stories.

With stuff like Ganges 5, where I was doing research, and then the research was leading to more research, on and on – it's an endless...

An endless spiral.

Exactly.

Maybe part of that is how you're accumulating a body of work. When you're working on Ganges 5 or 6, you're trying to link it up to the earlier issues. When you're making a short strip, maybe there's not that pressure.

I see what you're saying, but for me it's not hard to link things together. What's hard, or what has become hard, is keeping the focus on making comics pages.

Are you working on pages now?

No, I'm not. If anything, I'm still doing what we've talked about. I sit down and I'm reading several books. I read the books a little bit every day, and when something jumps out at me that sparks something, I write notes about it. But now I do it on notecards.

Have you thought about what might change that for you?

Just deciding one day, “Today we're going to write a script, and we're going to rule out pages.” Once there are pages underway, there’s momentum. I just have to get the momentum going. I just have to shift my habits a bit.

But at the same time, you're doing the Riverside Companion zines, and you're talking to people about The River at Night, so maybe that makes it harder to focus on new work.

I'm going to do the Companion zines for a while, because that material has all been sorted through and is ready to make zines out of. I'll be satisfied when a few of those zines are made, when some of that extra material is in its place.

Also, as a philosopher myself [laughs], I'm chasing down some ideas, and I’d like to put those ideas into a weird, personal cartoon language. That feels compelling to me. I don't want to be a pretentious, a “philosopher,” who's writing about the mind and all that, but I guess I can’t help myself, because I keep doing it.

Why does that bother you?

Just the usual stuff, about not wanting to be a cornball.

I think running philosophy through a sequential comics language, a cartoon language, and doing it well, it could be interesting and new. Who knows? I'm compelled to do it, and put it in some form that people can either get into or you know, reject completely.

When you get back to making finished pages, do you have an idea of what you'd like to work on?

I've already committed myself to drawing more Bona, and I'm working on this new Glenn Ganges story where he's waking up, and then he’s going to walk to the library. That's the basic framework, and I don't know what's else going to get plugged in there.

All the previous things I've ever done have started with me drawing a couple panels and not knowing where they're going. Pretty quickly they turn into something, and the whole thing unfolds. So I'll just try to do that again.

The whole book [The River at Night] is about Glenn trying to fall asleep, and I thought it would be funny to start the next story with a groggy Glenn who is reluctantly waking up. It seemed like an obvious joke. Then that evolved into...I was thinking about his spine as he's sitting on the edge of the bed, and breathing. So one thing leads to another.