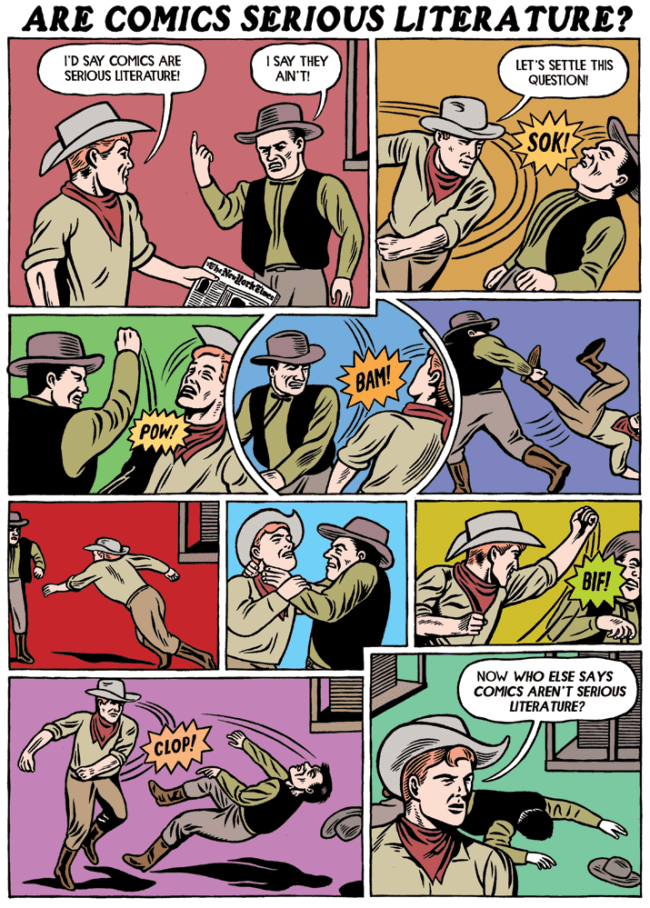

Until recently, Michael Kupperman’s comics were not really about anything. His surreal humor—see: Snake‘N’Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret and two volumes of Tales Designed to Thrizzle—defies easy classification, partly because Kupperman’s style is pared down to a deceptively simple level. If anything, his comics sometimes read like Kupperman’s impossibly warped remembrance and celebration of the comics medium’s early juvenile roots. In his humor collections, you’ll find the shaggy-dog-style adventures of the Hamburglar and Pablo Picasso sandwiched between fake ads for sex robots and cover galleries for comics about Quincy, M.E. and St. Peter. Nothing makes sense, but some things recur anyway.

Until recently, Michael Kupperman’s comics were not really about anything. His surreal humor—see: Snake‘N’Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret and two volumes of Tales Designed to Thrizzle—defies easy classification, partly because Kupperman’s style is pared down to a deceptively simple level. If anything, his comics sometimes read like Kupperman’s impossibly warped remembrance and celebration of the comics medium’s early juvenile roots. In his humor collections, you’ll find the shaggy-dog-style adventures of the Hamburglar and Pablo Picasso sandwiched between fake ads for sex robots and cover galleries for comics about Quincy, M.E. and St. Peter. Nothing makes sense, but some things recur anyway.

But while Kupperman says he’s gotten nothing but positive feedback from his readers—and has generally earned critical praise, as well as two Eisner Awards—he’s also underwhelmed by his collaboration with the book publishers at both HarperCollins (Snake‘N’Bacon) and Fantagraphics (Thrizzle).

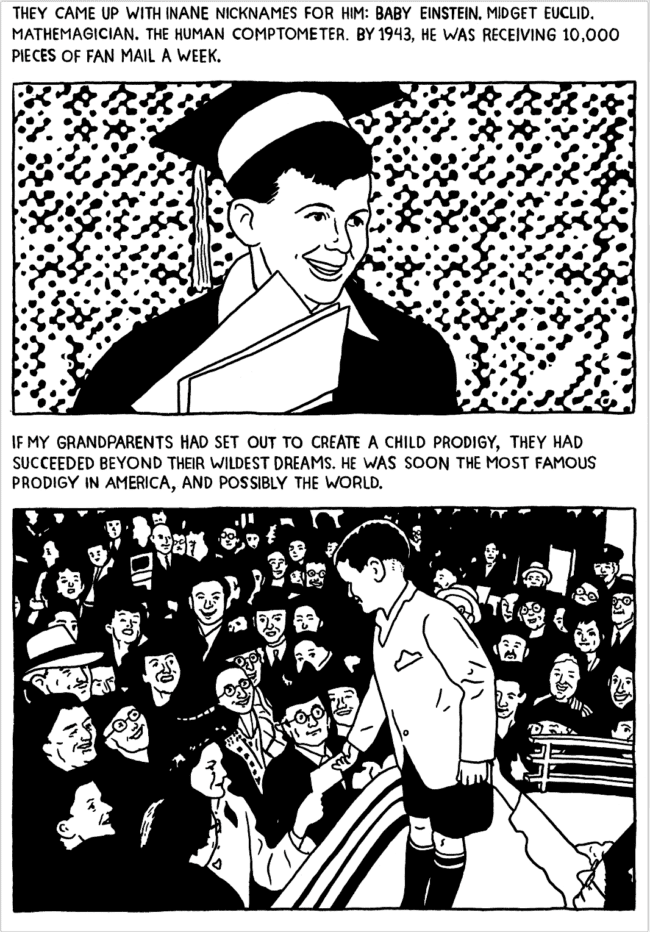

Last year, Kupperman released All the Answers, a graphic novel memoir about the psychological traumas that Joel Kupperman (Michael’s father) endured during his time as a young celebrity and quiz bowl champion.All the Answers earned overwhelmingly positive reviews and an Eisner nomination (Best Reality-based Work). But Kupperman still feels let down by his publishers (Simon & Schuster) and their promotion of his work. I recently spoke with Kupperman about the reception and release of his work, from his early comics ‘zine contributions in Hodags and Hodaddies (under the pseudonym “P. Revess”) to All the Answers.

Simon Abrams: Let’s start by talking about your work with the comics ‘zine Hodags and Hodaddies. This was in 1989, right after you graduated from art school. In an introduction to a collected version of those comics, you wrote: “To me, comics was nonsense, the disruption of reality" and that your early comics were "an art that was private but could be an invitation. It was powerful comedy." Talk a little more about that. How were you hoping, at that time, to engage with readers given the kind of collage aesthetic and just the way that your style, as P. Revess was kind of…it’s very experimental. It has more to do with collage aesthetics than I think most comics readers might be experienced with reading.

Simon Abrams: Let’s start by talking about your work with the comics ‘zine Hodags and Hodaddies. This was in 1989, right after you graduated from art school. In an introduction to a collected version of those comics, you wrote: “To me, comics was nonsense, the disruption of reality" and that your early comics were "an art that was private but could be an invitation. It was powerful comedy." Talk a little more about that. How were you hoping, at that time, to engage with readers given the kind of collage aesthetic and just the way that your style, as P. Revess was kind of…it’s very experimental. It has more to do with collage aesthetics than I think most comics readers might be experienced with reading.

Michael Kupperman: True. I was very influenced by other fine artists who had overlapped with comics who were mostly not well-known today, like Öyvind Fahlström, Jess, Robert Combas, Raymond Pettibon. There are many European “fine” artists who still work in a comic and pop art tradition.

I remember you cited Marcel Duchamp. At least, you quote him a couple of time in your earlier interviews.

Just as a patron saint of artistic disruption. But as far as being influenced by art I’d seen, I’d been working before that as an assistant for conceptual artists, so I think conceptual art ideas definitely played a part. And then it was European artists… I was seeing a lot of stuff that took comics language and kind of played around with it and disrupted it and made things. What I felt happened with my work when I started doing comics for Hodags and Hodaddies was there was a very collage element but also jokes started to appear, and then eventually joke structures started to appear. And I started to feel like, maybe I could actually do something with this that’s original, but still delivers in some way to the audience. That’s the struggle that’s been going on since then.

Tintin seems like a consistent influence on your work, from your early P. Revess period to All the Answers. Not just in terms of influencing your style, but also in terms of the language and the foundation of your understanding of comics. Like, Hergé's clean-line style famously has that amazing combination of simplicity and dynamism.

Tintin, for me, is symbolic of narrative in comics. From my formative years, that was the narrative in comics I was most familiar with. So at the beginning, I used him a lot as a deconstructive symbol of narrative. In fact, I should try to find it, but I did a comic with a friend in college about Tintin’s dreams. It was mounted on cardboard and tied together with shoelaces.

Abrams: Wow, I’d love to see that.

Yeah, it was an early experiment. Tintin was absolutely… the only narrative I can think of, really, that I’d read up to that point. Everything else was episodic or humorous.

Well that’s one of the things that attracts me to that quote of yours, where you say that the art was “private, but it could be an invitation.” In other interviews, you’ve said that you weren’t especially concerned with who was reading Snake‘N’Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret. Before that: did you have an ideal reader in mind, or a kind of connection that you wanted to foster with the reader?

I think fostering a connection with the reader was very important. I do find that my work tends to attract or interest a certain kind of reader whose mental processes are…similar to my own.

Did you need anonymity to keep you feeling uninhibited when you wrote comics under the P. Revess name? That was before you started working with major outlets like The New Yorker…

That’s possible. I mean, I was brought up also with a 20th-century idea of the artist as a figure in isolation who does not have contact with the audience generally, and who can retreat, and the audience just sees the work. For me, from everything I learned, the work was the main point of an artist’s life. And I think that’s no longer true. It’s an important part of an artist’s life now to not retreat behind a wall. Very few can get away with it. So I think I was coming from that tradition.

In a lot of criticism, personal art is presumed to be better art. The idea that you have to literally bleed on the page to get people to take you seriously or to find your work “accessible,” which is another critical crutch. Was moving away from your collage-style work your way of making your art more accessible? That is: was it a conscious goal?

Oh yes, absolutely. I mean, I think there are very few artists who don’t want more audience. Yes, I wanted to make my work more accessible and have it read by more people. The thing about Hodags and Hodaddies which was great was: I would do these comics and then people I know would see them and comment on them to my face. That was really rewarding for me. That aspect to the work disappeared pretty quickly after that.

You’re now on Patreon. How has that worked towards your goal of fostering a more immediate connection between your readership, your work, and you?

You’re now on Patreon. How has that worked towards your goal of fostering a more immediate connection between your readership, your work, and you?

I think it’s still developing, really. Patreon is part of a more conscious shift on my part to make that connection and to build it. The old system has so consistently failed me. If I have a chance now to keep making comics the way I want to, it’s only going to be with the direct support of an audience that enjoys them.

Was it harder to be taken seriously by comics gatekeepers—both critics and publishers—because your style is not stylistically dense? You’re not exactly Chris Ware, who puts all the work on the page and kind of overwhelms you.

Absolutely, yes. I am not a designer per se and my work is not design-heavy. And yes, I think Chris Ware’s work, which is omnipresent now, has achieved that status partly, or mainly, because of its design sensibilities. I think design has really overtaken art in our culture right now. People think they’re the same thing and they’re not at all. In some senses I’m anti-design, and I see it as a limitation that our culture has placed on itself now, that everything has to be “designed” just so. I find the disruption caused by the human touch and the human brain to be much more interesting than something perfectly designed.

What do you make then of the popularity of artists like Michael Cho and Darwyn Cooke before him, guys whose cartooning has an ostentatiously clean but draftsman-like design?

I find that over-designed work is hollow and is not interesting as narrative. I’m sorry to say this, but I didn’t care for Darwyn Cooke’s work. I didn’t find that the stories that he illustrated—the ones that I read—worked as stories. I was too conscious of his style. I find that kind of over-stylization to always to be at the detriment of the writing and the actual experience of the comic.

Tell me a little more about how you think Cooke over-emphasized design over story elements. That’s an interesting comment.

Well, he was a stylist, and when you’re a stylist everything becomes subsumed to style, including character. So I find that if the work is overly stylized, it’s distracting. There’s a visible limitation placed on what can happen. I mean, I think two of the limitations on my career are possibly that I’m not a stylist and have never wanted to be. And I’m not particularly character-based, which is something that I might need to address sometime. But I find over-stylized work… it always, to me, detracts from the total experience of reading the work.

Let’s backtrack a moment to your P. Revess comics. What kind of response did you get to them, and how were they promoted?

My original work that I was doing for Hodags and Hodaddies and the years immediately following… New York was a very different place back then, and the comics community was pretty free-flowing, and much smaller. So you would have gatherings where nearly everyone involved in comics in New York City would be there, from top to bottom. You’d have shows that Danny Hellman mounted at… first I think it was Max Fish and later at CBGB’s gallery space. Anyone who wanted—any cartoonist in the city—could show their work at these events. So you’d have some top comic artists and then some people who were gluing chewing gum wrappers onto bits of cardboard. It felt much more like you were in an environment surrounded by other artists. For several years there, that was where I was. At the beginning, it wasn’t about getting my work out to the public. It was about really experiencing other artists and sometimes showing them my work.

We both used to contribute to the New York Press, though I think at different times. By the time I got there, there was already this pervasive sense that paying your dues while also waiting for a staff job was…naïve, I guess.

None of the old concepts are really that valid anymore and all of them should be examined and possibly discarded. I was brought up with a lot of 20th-century concepts about what an artist should be and what a worker should be, and most of those are not valid now. In fact, some of them I feel have held me back. I was brought up to work hard, keep my head down, pay my dues, and I would get rewarded. I think a lot of people of my generation believed that stuff, and it wasn’t true.

Abrams: Speaking of jumping head-first into a trench: tell me about your strip at the Washington City Paper!

The Washington City Paper. I was invited by them to do a political strip in, I think it was 1996, or 1997? And in those days I didn’t say “No” to any assignments. I think I was doing it at the same time I was doing another strip for the Seattle Stranger, Up All Night, a lot of which ended up in Snake‘N’Bacon. But as I remember, I did that strip for maybe a year, which is incredible because I was really awful at it. I had very little understanding of politics (just no insights) and I found the format so difficult to work with, possibly because so much of my attention was elsewhere, on my genuinely humorous work. I couldn’t see a way to make it work. Now I think I might have better luck. I’m a little more politically aware, I’m happy to say. I also probably have a strong enough toolkit now where I could handle something like that if I had to. But at the time, it was just a disaster.

Did you get the sense that you were expected to diagnose the political climate?

Well, clearly they couldn’t have expected me to have much diagnostic ability, especially after reading the first few strips I did! It’s bizarre that I was chosen in the first place. But no, the most important thing was to sum things up in a kind of humorous way, but not be too extreme in my viewpoints or what I was saying. I did one strip when Denver Pyle had just died and I drew a strip about people saying he was the “People’s Duke,” sort of poking fun at the Princess Di tragedy. I think that was the only one that kind of upset them. But yeah, I felt part of my job was to be as bland as possible, to be honest.

That weirdly reminds me of one of your previous TCJ interviews, the one with Jesse Fuchs where you recall that Andy Richter approached you at a New Year’s Eve party and told you that Snake ‘N’Bacon-style humor isn’t going to lead anywhere. In other words: when you aren’t bland, you get people saying, “Yeah, but there’s no job or sustainability in it.” In the Fuchs interview, you were worried that Richter was right.

He was right. That humor really hasn’t led anywhere. Part of me wishes I’d just not gone into comics at all and tried to go into comedy and perhaps things would be different for me. But as far as humor, I mean, it’s not really a commodity in publishing anymore. Even Kate Beaton was saying to me she’s not going to be doing any more humor collections because it’s not going to be salable. And I felt this through doing Tales Designed to Thrizzle. The enthusiasm for humor in comics is very low, and there’s not much place for it, which is why I’m going to be crowdfunding any humor collections I do from this point onward. I had actually completely forgotten that conversation until now.

Let’s jump ahead a little to your work with Adult Swim, because there’s a word that you use, not just there, but I see it sometimes in your interviews. There’s a sort of disclaimer on your site for the collection you put together of your Adult Swim work. Maybe it’s not a disclaimer. But you talk about how you were trying to meet the audience at its level, and therefore some of the work is “puerile.”

Let’s jump ahead a little to your work with Adult Swim, because there’s a word that you use, not just there, but I see it sometimes in your interviews. There’s a sort of disclaimer on your site for the collection you put together of your Adult Swim work. Maybe it’s not a disclaimer. But you talk about how you were trying to meet the audience at its level, and therefore some of the work is “puerile.”

Yes.

Why preface that work with that word?

At the time, I felt the work I was doing—my humorous work—had been largely ignored. This was after, you know, doing eight issues and two books of Thrizzle and then the Twain book and then the disastrous experiences at The New York Times and The New Yorker. No one was calling, no one was asking for humor. And I felt like puerility may have been one of the things I was missing. It was certainly a necessary ingredient for Adult Swim. You know, I feel like puerile humor does at least get attention sometimes, and I wasn’t getting much. So that was part of it.

When you started working for Adult Swim, did you have an idea in your head about not only who your audience was, but what you needed to do to reach them?

I was not thinking of the audience so much as I was thinking of Adult Swim itself. I was trying to impress them. I guess I was hoping to do another animated project for Adult Swim. And they did, in fact, immediately ask me to do another animated thing for them. So it worked!

I remember with reading some of this stuff, it just reminded me of another quote… this might be more to do with Vice, I’m not sure, but you said, “If I’m working for a place and I feel like the assignment is intensely stupid and they’re not paying enough, I think it does reflect in the work.” Is Adult Swim one of those places?

Oh no, no, absolutely not. Quite the opposite. They were paying quite well and I was really enjoying that job. I wish it would have continued. Honestly, I’d still be doing it.

So would you say that comment would apply more to stuff like, for example, The New Yorker or the New York Times, where you had great difficulty with editorial revisions?

Yeah. I feel there was a point where it did start showing up in my work for both those places, as the quality of the assignments I was being given to illustrate declined.

What’s it been like when you independently sell PDFs of your work for Vice and Adult Swim on your site?

Well, that’s actually been huge. I mean, the past ten years especially have been intensely tough, partly because I had a child and that puts on a layer of pressure that is just, I think, unimaginable to anyone who doesn’t have a child. I couldn’t have conceived what it would be like, but it’s been just incredible. I haven’t ever regretted it, but it has brought this incredible layer of pressure. And then the declining economy, the decline of publishing… it just felt like publishing, to me, was saying, “We don’t know what to do with you. We’re giving up.” So then I worked on this serious book called All the Answers that came out last May. The publisher, apparently, had no budget for promotion or travel and I really was mostly promoting that book on my own. It was intensely dispiriting; it felt like I had really poured my heart and soul into this book that I still am quite proud of. I did what I set out to do. And yet, in general, the culture was mostly saying “No thank you.” It was very hard.

I really was thinking about quitting last year, if only I had any other talents whatsoever or any connections besides going to work at Trader Joe’s. But honestly, it was the reaction from people online and the fact that I did quite well, actually, for me selling art and signing books last year that really made me feel like maybe I can continue. I mean, some of the heartfelt reactions to not just All the Answers but my earlier, humorous work, really astonished me in their sincerity. I’ve always wanted to feel like I was doing something good by doing humorous work. If I could make people laugh… I thought that was a good thing to do. So to actually get that reaction from people really meant a lot to me. And then I actually made more money last year than I had in several years previous, and it was all, you know, mostly through selling my originals and selling signed books. So that was kind of, that was the great part of last year for me.

I really was thinking about quitting last year, if only I had any other talents whatsoever or any connections besides going to work at Trader Joe’s. But honestly, it was the reaction from people online and the fact that I did quite well, actually, for me selling art and signing books last year that really made me feel like maybe I can continue. I mean, some of the heartfelt reactions to not just All the Answers but my earlier, humorous work, really astonished me in their sincerity. I’ve always wanted to feel like I was doing something good by doing humorous work. If I could make people laugh… I thought that was a good thing to do. So to actually get that reaction from people really meant a lot to me. And then I actually made more money last year than I had in several years previous, and it was all, you know, mostly through selling my originals and selling signed books. So that was kind of, that was the great part of last year for me.

I’m especially struck by your parody of the Beetle Bailey 9/11 strip, the one you did for your Adult Swim Supervillains series. That was maybe one of your most caustic humor strips. Is it fair to say that sometimes you use your art to react against modern trends?

Absolutely. I was fascinated and appalled by the work that a lot of newspaper cartoonists chose to do on the 10th anniversary of 9/11. I find emotion in art, genuine sentiment, to be incredibly strong. For example, the Fra Angelico frescoes in Florence, if you ever visit there, are powerfully moving because of their sincerity. He believes very strongly in what he’s portraying and in the emotions he’s summoning. On the other hand, sentimentality in art is one of the grossest things and I always find it completely appalling, whether it’s a maudlin tribute cartoon or a comic book where they’re showing human victims, you know, appealing to the viewer. It’s always a horrifying use of the artist’s talents. I just find sentimentality appalling, and I want to mock it whenever I can.

That’s one of the things that stood out to me about All the Answers: by the end, you’re interrogating your motives, asking whether or not what you did was the right thing to do. Maybe I’m wrong, but I got the sense you would not have felt like that story could end any other way.

I’m glad you feel that way. The book actually had a different ending in the draft previous to that, which was much more about me exploring the effect that my upbringing had had on me and what it had made of me as a person. But I think I still was not done processing that aspect of the story, and those pages had a kind of, as my editor said, an “angry tone.” So I felt the book needed to be less about me and more about my dad, and it needed a kind of elegiac ending. There’s a part of me that feels like I used my father for career gain and that’s not a pleasant feeling. I have to answer that question for myself.

You recently said, in your Paris Review interview, that you felt like there isn’t a sturdy enough professional structure in place that encourages artists to develop their style. For All the Answers, and in general: what kind of support have you been getting and has it changed over the years?

You recently said, in your Paris Review interview, that you felt like there isn’t a sturdy enough professional structure in place that encourages artists to develop their style. For All the Answers, and in general: what kind of support have you been getting and has it changed over the years?

It rises and falls. I got support from a lot of places when I was doing the first Thrizzle book, like The A.V. Club putting me on the cover of their print edition, or when I did a signing at the Strand. But when I did All the Answers, The A.V. Club did not review me or mention the book at all and the Strand would not return my emails. Things come and go. But then there were new places that came up.

On the whole, I’d say: the general structure of support for artists has gone downhill. It’s impossible to escape that conclusion. Plus, when I started in the 1990s, New York was a much easier town to live in. You could have a part-time job, still pay rent, still do art the other times. The cost of living wasn’t as high as it is now, and jobs were easier to get. Life was just easier, in general. So there’s that aspect of it as well. As a friend of mine used to say a few years back, before he died: “The Age of Fun is over.”

Do you feel like people’s perception about your work changed when All the Answers came out? Like, did some critics give you the impression that they now felt: “Oh, this guy is actually serious!”

No, not at all. The people in comics who thought I wasn’t worth taking seriously still thought I wasn’t worth taking seriously. I mean, one of my aims in the book was to make it look easy. I think that’s always one of the goals in comics, and maybe I made it look too easy. But no, I felt the reaction in comics was very disappointing, to be honest. I was extremely disappointed by the reaction from the comics world. There’s been almost none, and there were people I’d worked for, where I’d told them they were part of the reason I was in comics, because of their work. They didn’t respond to me at all even after I sent them copies of my book. I mean, I was really hurt by some people’s reactions, to be honest.

I really was expecting something different. I thought, you know, the people in comics who I’d known for years would applaud it. That’s not why I did the book, obviously, but I really was surprised by the absence of reaction from certain quarters, and yeah, it was intensely dispiriting. I did think of quitting. I found last year one of the most emotionally stressful years of the last decade, and that’s saying a lot.

For the sake of full disclosure: when I pitched interviews with you for All the Answers, none of my usual outlets would accommodate or even consider a piece. The general response was: There’s no established audience for that kind of coverage. It’s too niche. I can move on from that rejection because it’s not my work, but for you, it must feel personal, right? That lack of response.

It’s pathetic what the media has become. They hinge everything on whether there’s an existing response for it or not, an existing market. No one has any imagination, no one has any courage. They only want to go by what has already gotten enough thumbs up on the internet. Publishing has soiled itself in the decades I’ve worked for it. As I said about Snake‘N’Bacon: the process of releasing that book shows how things went from the 20th century to the 21st. Avon acquired my book in a very 20th century way, saying “This is cool, we want people to see these cartoons, these comics.” Then they were acquired by HarperCollins, whose attitude was, “There’s no proven market for this, so fuck it.” And that’s been the major problem with my career up until now. Since I’ve had no major commercial success and I’ve had no major exposure, I’m not going to get any either! You know? It’s a complete Catch-22 situation. I think All the Answers could be a hugely successful book if someone was really behind it! But you know, living in this system you have to accept what you get.

Let’s go back to Snake‘N’Bacon for a moment. I know there was some frustration in part from the way HarperCollins handled it, but I also remember that when you were working on Robert Smigel’s TV Funhouse, I think I read that they tried to outright acquire a lot of your material before they’d even consider either adapting or working with it. Is that something…?

Oh, that’s standard for everyone. Comedy Central did that for TV Funhouse, Adult Swim’s lawyers did that with Snake'N'Bacon. That’s just how lawyers are. The New Yorker cartoon department has a clause that if you do a cartoon character more than once in the magazine, it becomes their property. I mean, you just have very greedy and ambitious lawyers trying to hustle whatever they can out of artists. The system is merciless.

Talk a little more about HarperCollins. How did they promote Snake'N'Bacon?

They did no promotion whatsoever. It was just sad, because Avon had been very excited. They had had me design the logo and the catalogue for this new book line called Spike Books. And there was a promotional plan involving cardboard book dumps, and they were going to do things to promote the book. And then when HarperCollins acquired them, that all went out the window and they did absolutely nothing. Since then, the only contact I have from them are sales statements, apart from one time when an editor who had inherited responsibility for my book contacted my lawyer to ask why so many people were searching for Snake‘N’Bacon on the internet after we had our TV pilot debut. I think we were the third-highest search or something. And we said, “Well, there was a pilot, Conan O’Brien just said it was his favorite book,” etc. They never replied. I mean, there’s no overstating the laziness of book editors.

Sounds like they were practically treating it like work-for-hire.

Yes. They’ve kept Snake‘N’Bacon in print, but for a while it was in a weird POD version that looked like it had been Xeroxed and slapped together. I don't know what you get when you order a copy now, but I hope it’s something that approximates how the original version looked.

Do you think the promotion of the book was held up by the fact that you’re doing adult-oriented humor that’s not really Meaningful or About Something?

You’re putting your finger on it. People these days like humor if it’s attached to meaning, if it comes with meaning. Part of my work, certainly the humorous work, has been that there is no meaning attached beyond the humor and the satires of narrative and communication. There is no other meaning. And I think that’s part of why it has not, you know, advanced as much as other things.

At the same time, readers are responding and have responded to my humorous work and the new book on its terms. They are responding exactly how I wanted [them] to. That tells me that my work is reaching people in the way I wanted it to, which means there has to be a certain percentage of the population – I don't know how big – that is my audience. I think publishing has been swallowed up by the entertainment industry, and it has swallowed the entertainment industry’s rules. And part of what has become common wisdom in the entertainment industry is only big successes are worth worrying about. Minor successes are pointless. I think no one has ever seen me as being a “major success,” and so no one has invested the thought, effort, or capital to, you know, make me a modest one.

Talk about how Fantagraphics promoted Tales Designed to Thrizzle.

Well, it was great at the beginning, for the first four issues and the first collection. Fantagraphics was really great to work with. I mean, they were always great to work with as far as production and taking the work seriously goes. They have genuine enthusiasm for comics and I think that’s wonderful. When the first collection came out, that was really the high point. Eric Reynolds was the person there who was most in tune with my work and who really got it, and he was very good at promoting it. I need someone good promoting me, and that was the one time I had it. So things went really well up till then, and the book did exceptionally well until they forgot to keep it in stock and it went out of print. But there were a lot of promotional opportunities that year. So I was very happy until then. Then Eric got promoted to partner, stopped doing promotion, and things just kind of went downhill from there. I didn’t feel like I was in tune with them anymore. In fact, I ended up wishing I had stopped working with them after that first Thrizzle book, because it just was going so badly.

Is that when the Eisner nomination came in, or was that after?

The Eisner nomination – or the Eisner win, actually – was kind of the culmination of that. Their new promotion person didn’t seem particularly interested in promoting my books. They are a great company, but they weren’t a great organization in many ways. There were instances of me showing up for signings and they didn’t even have a chair assigned for me, or a sign, or anything, and I just stood there doing nothing. 2013 was a terrible year for them: Kim Thompson passed away. That was terrible. But at that point, I was so unhappy with them. I was nominated for, and then won the Eisner, and they really didn’t seem to care. Someone from Fantagraphics told me, “No one cares about Eisners.”

I did one more signing with them, as I remember, which was at SPX. It was an awful experience. And they had a roll of Eisner-winner stickers that the Eisner people gave them to put on the books, and they kind of tossed them at me and said, “We were too busy. You can do this if you want.” And I was too busy signing books. I still have those stickers somewhere. But their attitude… they weren’t there for me at all anymore.

A few months later, I see on Twitter that they’re having a Kickstarter to support books for the following spring. One of the books is mine, a reprint of Thrizzle Vol. 1. They’d accidentally let it go out of print, forever capping that edition’s sales, and they were partly funding the paperback with the Kickstarter. And they hadn’t told me. This was a shock.

By that point, they had not paid me royalties for a long time. They’d started selling my work on comiXology a year earlier, and I still hadn’t seen any of that money. This was at a point where things were going really badly for me. I mean, not just in terms of money, but my father’s dementia struggle was intensifying, my son was having extreme difficulties in pre-school (it sounds ludicrous, but it was deeply unpleasant and stressful for us), and I had no patience left with Fantagraphics. So I wrote to them and demanded they pay me the rest of my money. That was it; I couldn’t trust them at all after that.

I remember you talked to Sam Adams at The A.V. Club about your Twain and Einstein buddy strips. You said: “I think the idea of being reduced to a stereotype is amusing, and when it’s a great writer being reduced to a lovable fuddy-duddy, I find that hilarious.” I thought about that after re-reading All the Answers; I wondered if your sensitivity to the way pop culture kind of recycles celebrities, not to mention intellectual celebrities, and refashions them into a cuddlier form… does that maybe come from living with questions about how your dad was treated?

Huh, that’s an interesting question. My immediate response is no, because he was rarely commodified to that level. Something I find appalling about our current culture, and I think it’s… I identify it as maybe more of a liberal thing than conservative. I may be wrong here. But there’s this constant need to take cultural figures that are respected or adored at any level and commodify them and fetishize them. This is true not only of cultural figures, but also of politicians. They are fetishized to a degree that is really gross at its worst level, and now thanks to social media like Twitter, we can all see how far that goes. So yeah, I’ve always found that amusing at one end and appalling at the other, this desire to take very complex people and turn them into something very simple, commodifiable.

I just saw yesterday a movie trailer for the latest Shakespeare biopic, All is True, where Kenneth Branagh approaches Shakespeare like an old Sherlock Holmes type, tending his garden. And the big question the trailer poses is, “Why did you stop writing, sir?” I wonder if you saw stuff like that as part of the pill-in-the-peanut-butter kind of mentality you're talking about, that need to make everything approachable and accessible.

Yeah, the imposition of narrative and very simplistic narrative tropes. There’s a diminishing set of tropes these days, I think it’s time for a complete overhaul. I don't know if you saw this strip I did for Huffington Post about the James Bond series when Sam Mendes started directing them.

I didn’t, I’d love to see that.

Oh yeah. I predicted he would make family relations central to the series and I was absolutely right, of course. And then Blofeld turning out to be his brother? It was like they decided to do Austin Powers, but as a tragedy.

Let’s get back to All the Answers. You draw yourself with these wide bug eyes and it sort of becomes clear why later on, when you show us how you hoped your father would succumb to a sort of hypnosis that would make him suggestible or just have a personal breakthrough. I remember Alan Scherstuhl, in his Village Voice interview with you, made a point of telling you that you drew yourself very harshly in All the Answers. Like he said: you rendered most of your other characters with a more human, or softer depiction. But you do go really hard on yourself in that one. I wonder if being stricter with yourself, depicting yourself in that way—was that part of the appeal? Like, a way of holding yourself accountable?

Yeah, I had to. I felt I had to. I didn’t want to do one of these books where I glide through like a tourist excusing myself of everything, and at the end the reader says Wait a minute. That doesn’t seem completely honest to me. I felt I had to be honest about myself; not harsh, but certainly as far as what’s driving the engine of the narrative forward is concerned. It’s me and the intensity of my desire to find out the answers to these questions. So that’s why I drew myself as being so intense. Plus: I am a very intense person, as you know!

Yeah, I had to. I felt I had to. I didn’t want to do one of these books where I glide through like a tourist excusing myself of everything, and at the end the reader says Wait a minute. That doesn’t seem completely honest to me. I felt I had to be honest about myself; not harsh, but certainly as far as what’s driving the engine of the narrative forward is concerned. It’s me and the intensity of my desire to find out the answers to these questions. So that’s why I drew myself as being so intense. Plus: I am a very intense person, as you know!

There’s a viscerally upsetting moment in All the Answers that I’ve thought a lot about since I first read it. It’s when you talk about how you’ve fantasized about traveling back in time and telling your dad to stay in England and never return to America. There’s a lot to untangle there, but I wondered if part of your response, or part of the emotion behind that moment, was the idea that American culture just couldn’t accommodate a personality or an intellect or a creative mind like your dad’s – or you!

Or even like mine, absolutely. One thing that’s not in the book is that we went back to Cambridge and lived there when I was a child, which in some ways was a repeat of his adventure there when he went to college. For all of us, it was absolutely liberating. I was 7 when we went and my sibling was 4… and it really transformed all of us. Culturally, Cambridge, England was just such an amazing place with theaters and bookstores everywhere, and such intensely smart people everywhere you went. It had medieval buildings, and a beautiful town, and countryside you could wander in. For me, it was the happiest time of my childhood. Then we came back to America and I think all of us, except my father, had strong memories of how sad that was. We could all see that the good times were coming to an end and that life was about to get worse, and we were going to be, I hate to say this, surrounded by dullards in a cow town. And we were. I think that atmosphere was absolutely fine for my father, but for the rest of us, I think, there were varying levels of trauma.

You allude to that, sort of, in All the Answers, in that scene where you quietly tell your dad that you’ve been expelled from school, but your father is just kind of in his own world and is therefore unable to process your news. Was that emblematic of your pre-teen experiences, rebelling to get his attention?

Yes. My father was extraordinarily bad at understanding other people, especially children, and communicating or seeing what he was communicating. When he was pushed to his extremes, he would become ridiculously angry and start screaming. When I was, I think, 12 or so, he found a Playboy in my room and just lost it. He was screaming at me about pornography: “How dare you read pornography!” Just lost it completely. All the 19th-century influence that had been pressed into him, the deep repression, became very visible. I was surprised and saddened when, two years later, he sat down on my bed and said, “Maybe it’s time for us to have a talk about the birds and the bees.” There are a lot of stories like that. I wanted to make the book as streamlined a narrative as possible, so obviously there’s a lot I left out. But my father was very confused by people.

There’s another story I almost put in from when I was older, when I was an adolescent. He was going out that evening and leaving me alone in the house. I was sitting at the kitchen table drawing. And he came in acting very worried and said, “Michael, something has just happened. I just had a call from a man who asked if there was a Maria here, and I said ‘No, I’m sorry, you have a wrong number.’”

“And he hung up and then he called back, and I told him: ‘I’m sorry, this is a wrong number.’”

And he asked ‘What number am I calling?’” I refused to tell him.”

“So I think now he’s going to be angry and there might be trouble. I should probably stay home.”

Of course I said, “Don’t be ridiculous, there’s not going to be any trouble. What are you talking about?” But that was his… he was absolutely baffled by other people.

That reminds of how my own adult interests were probably informed by the limits my parents set for me when I was a child. There were certain comic books that were presumed to be too violent for me to read, so they were hidden (very poorly) in the attic. And of course I found them! It seems so obvious now that that taboo of You cannot read this has informed my current love of gory horror movies. Do you think that the way that sex is depicted in your work, like Professor 69 or, what was that, the ball-sack character?

Feetballs.

Right! The way you depict more explicit stuff like that… I know you’ve gotten some notes from editors who have told you stuff like Oh, this is too explicit. Is that your way of testing the limits of what you can put out there?

Well, I think with the Adult Swim stuff, there was a conscious puerility which isn’t necessarily part of my makeup all the time. But yeah, it was also testing the limits for stuff I found funny. I will admit: I’m somewhat sexually repressed. I am. And it’s down to the fact that I was raised in such a prudish, hysterical environment. It left a mark on me, and I’m very aware of this as a parent. We’ve really placed no taboos on our son, but he has no interest in violent media whatsoever – and I’ve tried! He just doesn’t care! It doesn’t appeal to him.

How have you tried?

I’ve tried to show him superhero movies, or a Bond movie, stuff like that. But sci-fi, superheroes, spy stuff…he just has no interest in it.

Do you know why?

He’s not a violent person. I just don’t think violence has any appeal to him and he just doesn’t see the use of violence as being interesting in any way.

You’ve been putting up some of his own artwork on Twitter and YouTube. Before we talk about how you’re kind of trying to control the reception to his work: I wondered if you see your son’s interests and his preoccupations in his art, and if that’s changed the way you relate to him.

Oh, absolutely. His work is fascinating. He’s an artist at a really profound level. Because we have encouraged him and not placed any blocks on him, which is what both my wife and I feel was done to ourselves. I’ve struggled to overcome these preconditions whereas he’s been really free to roam conceptually. He uses art in just the most fascinating ways; he’s a conceptual artist at a very sincere level. So he’ll do drawings of things and they’re fascinating and really accomplished.

But then a lot of his work is… he’ll do diagrams over and over. He’s obsessed with subways. He’ll do the subway maps, both real and conceptually. He makes conceptual subway maps all the time for imagined spaces, for his own imagined space, for other people. He kind of uses conceptual language to take stuff and reconstruct it and break it down for himself. When he was in his last school, which was an absolute nightmare experience, his teacher was using a program called Classroom Dojo to enforce discipline, and then he had another one (the name of which I can’t remember) for classroom seating, a different app. My son went on the computer, downloaded these apps, registered himself, made his own seating plans, and his own Classroom Dojo account and gave out his own scores. He uses conceptual thinking to tackle all these things in the world, and it’s absolutely incredible to watch.

Is he at all interested in architectural design?

He’s very interested in architectural design. He’s gone through periods where he’s absolutely fascinated by plumbing and the interiors of things and how they work. He does a lot of drawings of diagrams and different things. Yeah, that’s also one of his interests.

How old is he now?

10.

I ask about his age because I know that, with the stuff you put on YouTube and Twitter: you’ve been wary of him gaining more than a cult following. I wonder how he’s responded to the feedback you’re getting for his work so far.

He’s very excited that people like his work. If you see him in person: when someone he doesn’t know well is genuinely responding to his work, he’s delighted in a very pure, wonderful way to watch. I think it would be obvious to anyone who’s read All the Answers why I would not want to promote him past a certain point or put him into public visibility past a certain point. He’s a very beautiful kid. I can say this objectively. He has an amazing personality. I don't want to put him out there for people to become obsessed about – although he craves attention. He’s very photogenic. I think he’s got an amazing future ahead of him. But we’ve all seen how harmful too much exposure can be to children. I don’t want him to be a successful child; I want him to be a successful adult.

In 2002, you didn’t have a credit card or a cell phone. I assume that’s changed since then?

In 2002, you didn’t have a credit card or a cell phone. I assume that’s changed since then?

Oh yes. Well, I have a debit card and of course I have a cell phone now. But yes, I only got a computer in 2000 and you know, I’ve been slow in some ways with technology. I only got a light box in 2007, so everything before then was absolutely drawn by hand. It’s only when I started doing animation that I learned the power of tracing. But yeah, I wasn’t… I mean, I wasn’t making that much money, especially after 2000 and the economic collapse that happened then. And cell phones weren’t that appealing to me. This did cause some troubles of course right after 9/11, because I was in the downtown area, where there was an army barricade on both sides of my neighborhood. And you needed ID to get through that or return to the neighborhood. So I was effectively stuck in the East Village for, I don't know, a few weeks or a month.

The instant I was aware of the economic collapse of 2000 (I illustrated it for the cover of Fortune), I just knew that things were going to go so much further downhill.

What’s the next thing for you?

What’s the next thing for you?

Well, there’s a lot going on right now. After All the Answers, what I wanted to do was do more work in that vein. But since it was not a conspicuous success, I felt like I’d been stopped dead. Still: I’m going to do more work in that vein. I have a piece written and I’m going to do it this month. I’ll print it as a mini, the first mini I’ve made in twenty-five years. I should have it ready for the Chicago CAKE convention and then, maybe, the story will also be on my Patreon. But I have more work I want to do, for myself as well as the reader.

I feel like I have such a bigger toolbox now after All the Answers and after the last few years. As you know, I was doing All the Answers and two weekly strips at the same time. I did a frightening amount of comics during that period. So I feel much more powerful now as an artist. And now that I’ve mostly put the horrifying experiences of last year behind me, I’m ready to pick myself up and try again. So I am planning to do a Kickstarter for a new volume of Thrizzle. I also have an assistant now, the person that’s been helping me sell artwork and books, Sonya Kozlover. We’re making prints, we are starting to experiment with printing small editions of things. We’re working on a magazine collection of Supervillains, the Adult Swim strip, right now.

And then beyond that: I have an idea for another, more mainstream book that I am going to try to pitch to a publisher. I need to find a publisher who is for real, who has some experience, and who will stand behind the book after it comes out. And if I can’t, then I’ll publish it myself. I want to do more funny stuff, I want to do more sad or serious stuff. And I want to start to combine them.

Do you feel like readers are now starting to become invested in Michael Kupperman and your progress as an artist? That is: do you feel there’s more interest in where this stuff comes from?

Well, I do think doing All the Answers gave people a kind of view into me for a change. And for some of the people who have been following my work, that has been a progression that they’ve responded to. That part of it has been very rewarding for me. People say Twitter is toxic and horrible, and of course they’re partly right. But I love it and it’s actually given me the support that I needed to continue. Without that, I don't know if I could have, you know? I’ve received a lot of support online that I needed and I wasn’t getting anywhere else. It’s meant a lot to me.