SENECA: Talking about still feeling like a kid, that sense is obvious in your work. It feels very youthful, and it always has, and that feeling doesn’t go away. Dealing with younger characters, the basic confusion of youth, and then in your paintings these pure cartoon symbols… It’s interesting because in comics I feel like there’s a need to be considered as “real” art or “literary” comics. There’s a push toward dealing with more adult themes and older characters…

PANTER: For young cartoonists?

SENECA: Yeah, there’s this sense that you have to go past the fantastic or the youthful to even make serious work.

PANTER: Maybe it’s because people are trying to be serious… in the art world too, it’s like now you have to do research. You have to research some doctor in Africa, and base this whole… it’s like museum presentations almost, what art has turned into. That’s what’s happening now. I think comics are a really expedient way of getting cheap effects. That’s what Jack Kirby did. Who was making movies, and make it explode, and make it blow their minds. I’d really… to me novels are an amazing form, I think they’re magical. I admire them. Short story writing is amazing. And I don’t go to comics for those things, I go for somewhere else. I can read a serious comic -- Chris Ware is serious comics -- but you’re also looking for visual titillation, or kind of… kind of the drug of the thing, you know?

SENECA: Do you try to keep the novels you read separate, and not let that bleed into your comics as much -- do you see them as separated things?

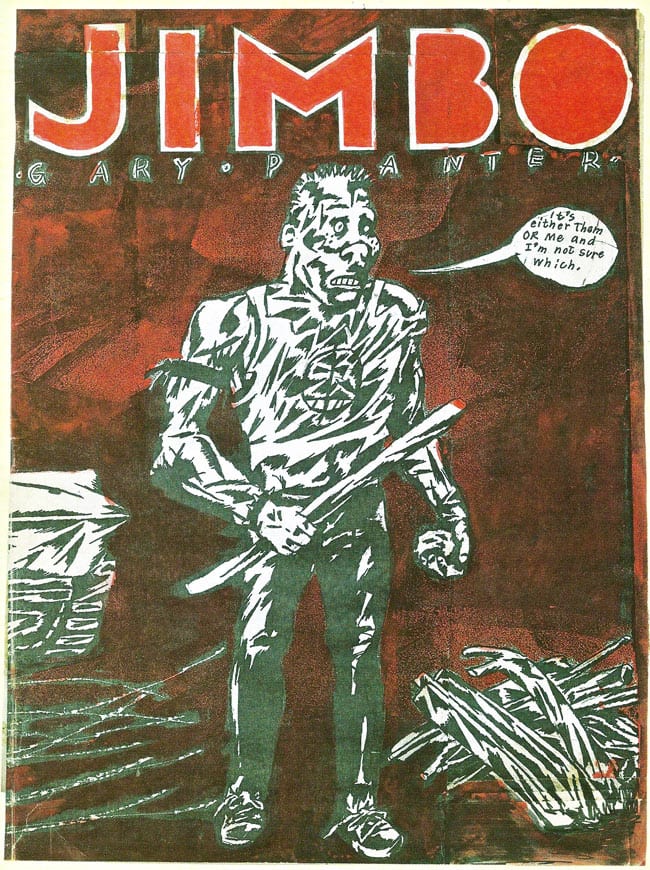

PANTER: I’d like to be more literate, and I’d like to make comics that are intelligent and could express things that are relevant to humanity. I’d like to write more, I write a little bit more now. No, I just try to be informed by everything. Like, in my mind there’s a bit of Edgar Varese going on, where you don’t necessarily see it. Or a bit of Gilbert Sorrentino is passing through, you know? The Dante thing was really purposeful, this conundrum of trying to make a complicated knot, a Gordian knot of associations. That was really what that one was up to, but these [current Jimbo comics] aren’t… I don’t have to think about referencing or anything.

SENECA: Was that attractive to you, to just go back to something simpler?

PANTER: It sounds like a joke, but the most experimental thing I can do at this point is to do something conventional, because I haven’t really done that very much. Though there’s still formal elements from my experimental stuff. I don’t know if I need to prove that I can do that or not, but I think it would be nice to show that I can do something that isn’t just experimental stuff, to show that I’m not just jerking off. Really it’s a game, that’s what’s obsessive about it. You’re entered into this dream space, and you can manifest it if you sit there long enough. And: We’re impermanent, and these things can be -- they can last ten minutes more. I don’t know what the significance of that is, but there’s an impulse to do that for artists. It’s probably vanity, like Dante was trying to make a spaceship to send himself into the future. He did it!

SENECA: He did it, yeah.

PANTER: He was a fuckin’ genius.

SENECA: Do you feel that because comics do last you don’t need to necessarily address concerns of aging within the comic because a comic doesn’t age as much?

PANTER: Aging as a topic of the comic?

SENECA: Yeah, or just in general. As an idea behind the comic.

PANTER: I think it’s all trying to avoid death, in some ways. Just keep playing with this clay! It’s total avoidance. “I’ll keep trying to be somebody!” Again, it’s vain. But it’s better than sitting around depressed or screaming in a loony bin or something. I’m an optimist, I believe art can help. But I don’t believe it has to go dig wells for people. You don’t have to call that art. You can -- but I think art can operate from a very selfish, solipsistic… but outward-looking still has to be important. And it has to still help humanity. And I’m very much, as everyone knows, part of the hippie generation, which was “We’ll get in spaceships and we’ll sail off into the future and wear groovy clothes,” you know? The downside was like “hey, spare change?” and like “oh, you’re pregnant,” but the visionary part is still cool.

SENECA: With that being said, is there an ideal reaction you’d like your audience to have to your work?

PANTER: I don’t think so. No, I think it’s really this game I play… I’m not trying to get an unfavorable reaction, definitely. The family I come from is always going to be disappointed that this was what happened to me, and at the same time mystified by it and kind of admiring. That’s a complex part of the equation, the offerings rejected. But that’s often the case, I’m thinking, in a lot of ways. Which is what makes the Zen of it really important. The reconciling of the opposites, and dropping those infantilisms.

SENECA: Is any of your work specifically inspired by that relationship to your family?

PANTER: I’m just trying to find out what I can do. There’s a part of me that acted out and a part of me that didn’t act out. I went in two different directions, actually. I could have been more extreme and at other times I’ve been too extreme. But past that I’m just trying to be myself, and okay, if they can handle that, fine, and if they can’t, well, too bad. And if it makes them unhappy… whatever. And with the internet, people can find things now. That can’t be an overwhelming thing, you have to grow up.

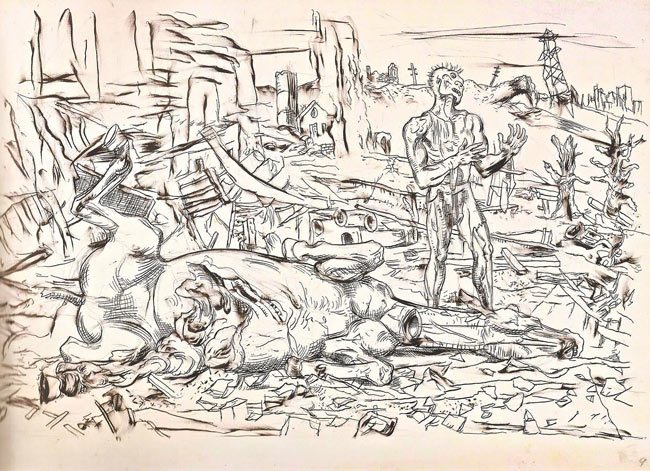

SENECA: That’s interesting, because all your comics I can think of take place against a fairly harsh landscape. Is that something that you’re consciously trying to depict or is it just something that naturally comes out?

PANTER: I guess the landscape I grew up in, I was looking for the interesting looking parts. If it was just a pile of pipes or a berm of sand, that was interesting looking, and if there’s terrain, that’s interesting looking, if there’s water that’s interesting. And I’m drawn back to Texas landscape, and to desert, and to Mexican landscape.

My friend Max Watson, who’s writing the introduction to the Dal Tokyo book -- a childhood friend -- is trying to make the case that everything I’m doing is just re-portraying the town I grew up in, Sulphur Springs. He does the whole -- from the geological point of view to the history of the town, he tries to make the case in the introduction. It’s pretty funny. Bill Griffith has this theory that everyone is trying to re-create what they were into when they were 18. Whatever moment their sexual peak was, that’s what they’re trying to reinvigorate. There’s some truth in that.

SENECA: [Laughing] Coming from Bill Griffith that’s really strange…

PANTER: [Laughing] Yeah, Young Lust comics… or before, actually. He would have been an idealistic youth going into art school and having to do abstract expressionism or something.

SENECA: So where were you at when you were 18, were you in LA yet?

PANTER: No, I was still in Texas, going to church three or four times a week. I was a missionary to Belfast in 1969… and, um… tortured. Tortured by religion, really. I didn’t really do any kind of drugs or drinking or anything until I was 20 or 21. But it was hippie times, you know? I mean, the information was totally fascinating, what was exploding all around, it really was… it’s such a cliché, you can’t really exaggerate what the climate was like. Because it was coming from such a backward moment.

SENECA: Do you think that sense of the religious, and conflict with religion -- especially if that’s what you were going through at that particular moment in your life, do you think that’s evident in your work?

PANTER: Yeah, because there’s systems of control. In Jimbo comics there’s often some sort of system that -- it’s a lot like Clockwork Orange. There’s some system that thinks it knows better than you that’s trying to enforce morality or good behavior on you that works to your determent, ultimately. And I don’t think that’s totally true but that’s often the metaphor that I’m making, some well-intentioned monster. Another thing I’m coming at is really just the architecture of things. Making these models, envisioning the place, and finding a way to codify them so you can believe in that place.

SENECA: Do the models ever dictate the story?

PANTER: Yeah … or they’re the jumping-off point. The one before this was the story of the Reggae Mouse, did you see that minicomic? That came out of an idea about a seaside place. It was this compound that I’ve been imagining building… this place is really almost sickly. It’s in my mind about where I’d like to be. Having this be part of it really dictated a lot of what I had to draw. I built a little billboard on, you know, Vegas terms. And that one was about Jimbo’s billboard. Then this [current] one is taking place in Zipper's gas station canopy place.

SENECA: So you make the models first and then draw the stories about them?

PANTER: Yeah, super simple models. Like that one I showed. Just so I can envision the size of the rectangles.

SENECA: Would you make them not even knowing you were going to draw a story about them?

PANTER: Yeah. They’re places I’ve obsessed about, and I’ve decided “OK, I should use this for something, I’m not really going to build it.” I do fantasize about really building them. It’d probably be dangerous if I had a lot of money because I’d start building them in real life. These pointless places.

SENECA: People would live in those.

PANTER: Yeah. It’d be pretty primitive [laughs].

SENECA: That could be a way to make a lot of money. If you build a three-million-dollar compound with a junkyard tin shed…

PANTER: I would definitely move into it. That’s my ideal, it would be to have a junkyard fence with a modernist house. Yeah, I could definitely do that, I’d definitely... yeah. But… this is a pretty nice house.

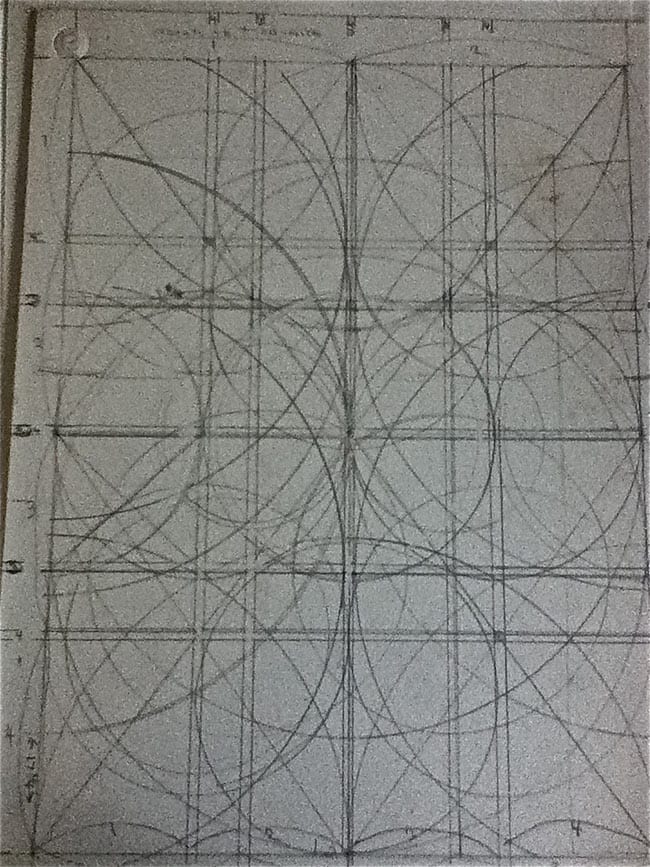

SENECA: Yeah, this is a nice house, too. I saw your grid map, do you map all your pages?

PANTER: In some sense, I’m thinking about it. Like I said, thinking about not repeating. Conscious of what comes next and what it does to your attention, how you’re processing information. So, sometimes in my comics you’ll see like: first panel’s one page, the second page is two panels, three panels, four panels, to six. And then it backs up because it’s trying to draw you in and then let you out and draw you in again. So there’s things I think about that way. And these are just… this is an overelaborate version of that, but it’s basically simple, just subdividing that rectangle. My friend, you know, Frank [Santoro] is totally, insanely into all that stuff.

SENECA: Yeah, Frank is nuts about these things.

PANTER: Yeah, and I don’t totally… I mean, I recognize the truth of it in a way. But that’s not part of how I organize things.

SENECA: So you won’t compose along these lines, necessarily?

PANTER: This is basically just like, half the page, a third of the page, a quarter of the page … it’s the variation of the box sizes I would use that I would be comfortable with. There’s not usually like, Will Eisner layouts in mine. Or there’s not usually tilty boxes or anything. There could be, but that would be trying to do something. Early, I was really into asymmetry and tilts, precise… barely tilting things and increasing the tension on the page by doing that stuff. But maybe with age, I’ve moved more toward the convention, the fascination, the pleasure of just inking a box with a brush or a ruling pen. Yeah, ruling pens… some tools are really important.

SENECA: So you’ve never had the temptation to do a wild Jim Steranko layout or anything, just go nuts with it?

PANTER: Well, I guess I’ve done a lot of psychedelic comics that are trying to be elaborate and weird, but no, I’m not really a fan of that. My friends in the Residents are like, way into that kind of stuff. But I just really like Superboy… and “What If Jimmy Olsen Was A Beetle”…

SENECA: That one where he goes back in time and sells the redheaded Beatle wigs, have you seen that comic?

PANTER: Oh, I don’t know if I’ve seen that. Sometimes he turns into the insect version of himself. But yeah, having to be a beetle, a Red Kryptonite beetle. Or a replacement for Ringo -- yeah, all that stuff’s funny. But it has clarity, and that’s a lot of what I haven’t had in my comics, is clarity. A lot of times my comics tend to go gray.

SENECA: Are simple layouts a part of that? Just make it as clear as possible?

PANTER: The way to do it, basically, is using more of a Japanese aesthetic and leaving white space and using intelligently placed black shapes. That really helps that. But I’m being careful on these pages more. They’re trying to be like 18th century drawings in some sense. The composition is a little bit of that, but not slavishly. The ones that turn gray are more like Cubist comics, where I just keep filling in, filling in…

SENECA: Crumb is another guy who has gone back to 18th century woodcuts. Have you talked to him about that?

PANTER: Well, he’s way into Nast, and I am too. I look at that crosshatching system -- now he’s more into Brueghel. I talk to Crumb a little bit. I haven’t talked to him… I figure that he’s a really busy guy. I’ve written him fan letters, but I don’t think I can get Crumb’s love. I think he likes me OK, but he’s got a lot of people in his life and he’s busy. So I can’t really expect anything from Crumb. He did come see me and Matt Groening in Hollywood years ago and met with us for a day. He’s always been very nice to me and everything. But I just think he’s put upon. I couldn’t really expect, like, “you should be my big brother,” I don’t really need that from Crumb. I just admire the hell out of his stuff. I mean, it’s amazing. The consistency in his work is kind of unreal to me. I think it must flow out of him. It looks like it just flows out of him without stopping. I’m more like, finding it every time, every day.

SENECA: Was there something you weren’t finding in more typical cartooning that made you feel like you needed the work of those older artists?

PANTER: Well initially I was just trying to do hippy comics. I just really wanted to be like the Zap guys because I was into experimental art. I thought, “Wow, here’s a moment when painting and comics have kind of collided a little bit.” So I was interested in pushing that. And I guess as I’ve gotten older I’ve gotten more like, “How do I like to draw,” and “How do I like to set up a page.” I’ve done a lot of experimental stuff and so now I’m trying to do this more conventional stuff. It’s very satisfying. I’m using what I can do. I’m not so much trying to do what I cannot do. It’s not that I’m not pushing it, but its like…. You know, Steranko: I wouldn’t have to go there. There’s a lot of other places I have to go and have already explored.

SENECA: Is something similar going on in your paintings, where you’re [currently] using less black linework and trying to pare back a little bit?

PANTER: It was just something I thought about doing and never -- and the paintings always wanted the black lines. As long as the paintings wanted the black lines… but then I reached the painting where it was like “oh I don’t really have to have a black line here.” “Oh I don’t really have to have a line there!” Also, if there are black lines, they’re not really black, they’re usually some black or gray or blue or some subtler color.

I guess I like to do 10 or 20 paintings that are related and then there seems to be kind of a natural step. I expect that lines would come back into my work. I’d be surprised if they didn’t come back, but I’ve got a lot of area to explore after not doing that for 30 years. Also right now I’m not really using patterning that much. I really like patterning and having little symbols for brick and gravel and stuff like that. So that might change.

SENECA: Is there a big difference for you between making lines in paint and making lines with ink?

PANTER: Yeah, the tools are completely different. Earlier on I was working with rapidograph more for my finished art and also using kind of a fountain pen that became obsolete. I was always struggling, because I’m left-handed, to get the ink to come out, period. Which was part of the reason for the ratty line -- rapidographs that jammed and things that didn’t work -- but I always liked woodcuts and lines like that. So I was like, “Oh, okay, I’ll just go with it.” But when the G pens, the Japanese cartooning nibs came out -- they’re sharp, and the steel’s nice, and as long as they’re making them I’m happy to draw like, you know, how I want to draw. I use long stripey brushes to do the boxes… it’s pretty conservative. I mean, for all my experimentation there’s something very conservative going on. I’m not just like flailing around at every possible thing. There’s these programs.

SENECA: You’re not using a brush line on these [Jimbo] pages at all, are you?

PANTER: Not on these, but on the one with the Reggae Mouse, that one was a classic brush line. Which… I mean I’m doing the blacks with brush, obviously. Only these boxes are brush. These lines are all like… this one [of the Reggae Mouse], that’s brush. And that’s the big gag in the strip, if that’s not irritating. Cause he’s really stolen from the funny animal comics from the '50s.

SENECA: Yeah, well Big Daddy Roth…

PANTER: Oh yeah, that’s funny. I didn’t even think of that. I was thinking of the animal comics from the ’50s. But it does look a little like that I guess.

SENECA: Yeah, that Birthday Party album cover is what I immediately thought of.

PANTER: Oh wow, that’s interesting. I completely missed that.

SENECA: Well that one especially, because it is the brush line.

PANTER: And that was a ’50s thing, Masters, the Fago Brothers…

SENECA: Is there any particular funny-animal comics that you liked? Carl Barks, or what was it?

PANTER: Well, Carl Barks is his own world and he was excellent. And I like the crappy ones. I do like the Fago Brothers. I like the one that are horrible and retarded and badly printed and some kid wrote their name on it and colored it in with a crayon… I like comics like that, they’re funny. But comics that were interesting to me in that Carl Barks way were -- it was this secondary strip in Bugs Bunny comics, Wuff the Prarie Dog. It was drawn in this really weird creepy style and the wolves weren’t kidding. They really would eat -- if they caught the prairie dogs, they really would eat them. And there was this strip that wasn’t so wonderfully drawn but it was kind of Alice In Wonderland-like called Mary Jane and Sniffles the Mouse. It was like a cute mouse and a realistic girl, and she shrunk down and had adventures in sandboxes and stuff. My favorite comics were probably -- I like Daffy Duck and stuff like that, but those were bad. Most of them, either they look like they were drawn by animators or just drawn by complete hacks who didn’t know what they were doing. Porky Pig comics. But Turok, and Magnus, and Tarzan had Brothers of the Spear… Russ Manning and Jesse Marsh are really wonderful.

SENECA: Do you feel like those guys’ influence is visible in your own comics?

PANTER: Jesse Marsh, yeah. I remember having the coloring book that this came from. [Gestures at the framed original Jesse Marsh Tarzan drawing on the wall behind him.] That’s an original drawing. I could recognize it as the same guy that’s drawn this, that’s the same guy cause the lines are the same, even from when I was a little kid. Yeah, everything has an influence. Thomas Nast, all the underground cartoonists. Originally, this [minicomic] I’m working on was the utter incarnation of Robert Williams meets Victor Moscoso. I have fantasized about doing a real hippy underground comic sometime that tries to really slavishly mix those guys together more.

SENECA: Put it out as a single issue, magazine-type thing?

PANTER: Or just another project — a 40-page comic or something, 32 pages. ’Cause I started some hippy comics at the very beginning, but I never followed up. They were just kind of bloopy shapes that accumulated. You know? Everything’s kind of trite. [Laughs.]

SENECA: [Laughing] Trite isn’t the first word I’d use, but do you think that sense of sort of the fantastic, I guess, in your work… like, the general thing with noncommercial comics is to make it realistic. Ware is realistic, or even Dan Clowes. And with yours, it’s weirder because it’s further out there… but then in commercial comics it’s always far out, it’s always some superhero thing.

PANTER: Yeah, right. I got that in common with them. It’s weird, there’s a lot of incredible drawing going in the film industry and gaming industry and comics, so I can’t say that I can really compete with that stuff. I’m not sure. I’m just more interested in Arabian Nights and Alice and Wonderland. I really do not like reading comics of people standing in bars talking to each other. That to me is just dead. I mean, I don’t like bars. If I liked bars better, I’d probably like it. The level of discourse is so low and repetitious and needy in bars, it’s just… gee, I’m not going to go there. I’d rather get on a scaly dragon or chase unicorns. Anything!

SENECA: Do you think that fantastic settings lead to a more elevated level of discourse?

PANTER: No, not necessarily. All of the fantastic drawing that’s going on is mostly just in the name of brutality: “I’ll blow your fucking head off with my gigantic --”

SENECA: -- ray gun --

PANTER: -- yeah, whatever. The argument that goes on about my work, about whether I can draw or not, has to do with that, which is pure facility: are all the muscles in the right places and stuff? I’m more interested in if it takes you to the place I’m trying to take you as the reader. I’m not interested in the muscles. It’s like -- [points at page] that’s not an elbow. I’m a limited drawer. I don’t think it necessarily makes it a better comic if it looks like Transformers. I like Transformers, but I’m not competing with that.

SENECA: So the drawing is strictly a vehicle for that transportative --

PANTER: There’s pride in it and craft and so on, but that’s not the end -- that’s not all I’m trying to do. I’m really trying to… again, in some crazy way, make some kind of triggers that incite people to evolve, instead of go back. I don’t know if you can do that or not, but I think that’s one thing that art is up to. It’s trying to make triggers that are evolutionary, or cultural, or some sort of… Like the model building, it’s modeling. It’s modeling possibilities, so many possibilities: A little object becomes a building, and the building becomes the ethics of the new world…

SENECA: And then it sticks in your imagination.

PANTER: It’s totally vain and in my imagination for sure. But I think that’s what art is trying to do. Not every art, but the art I feel close to. Peter Saul, here’s a guy who’s trying to do everything wrong, mess up your hair and indict humanity, and still, it’s like he’s trying to give good advice at the same time.

SENECA: How do you feel about your comics work being shown? The Galerie Martel show has comics pages and paintings…

PANTER: Well, it’s more the nature of her gallery, that’s what they do more, and I knew that going in, but that’s what she wanted to do, so it was OK. It’s not something that I’m usually trying to do, though. When Dan [Nadel] curated the show at Clementine, he wanted to include more of that stuff. When I’m in here, I like being in this room and trying to make things, but it’s a wreck and it’s distressing. But a lot of people come in here and they either get confused or they want to recreate it somehow: “We’ll take your whole studio and we’ll set it up at the gallery.” Which is kind of a nightmare, theoretically impossible. But I mean anything can go.

SENECA: In the books, how do you feel about The Land Unknown’s kind of mixed-media presentation as opposed to just a book of paintings or just a minicomic or whatever?

PANTER: Well there’s two catalogs [The Land Unknown and The Wrong Box], and one was for paintings and this one was more for comics. And I love it. In some ways, I told him, “Go crazy.” I didn’t do this book, Blanquet did this. Just do what you want to do and you might just find out something. So yeah, I love it. He mashed everything together, and I would never propose doing it. Resurrecting the William & Percy strips, I thought they were funny when I did them, I cringe a little bit now, but if someone likes to read them, then good.

SENECA: Yeah, this is like your gag-strip book almost. I thought they were all funny.

PANTER: Oh, good. I think my stuff is pretty funny, really. The Dal Tokyo, a lot of times it’s being so odd there’s nothing you’re getting from it. It’s kind of like listening to the radio static or something.

SENECA: Those feel very serious to me.

PANTER: They are, but they are playful, too. When the book comes out, I’ll be really curious to see what you think. It’ll be 200 pages, and it starts with a very coherent science fiction story, and then it just goes into the Twilight Zone, yet I’m still envisioning the science fiction story, and it comes back into focus for a moment at the end in some ways. And I was also kind of living through it, ’cause it was going on so long. From ’84 until this year. I just stopped drawing Dal Tokyo. They aren’t making a paper Riddim [Magazine, the Japanese periodical Dal Tokyo was serialized in] anymore.

SENECA: Oh, they’re not? That’s too bad.

PANTER: So I started the next story. After 200 strips, I started the story where Jimbo had a girlfriend and became very domestic, and it actually kind of got paralyzed. Maybe it was getting boring at that moment.

SENECA: So did you not mind as much that you weren’t going to be drawing that strip anymore?

PANTER: At that moment I was ready to stop. After I had done that completely crazy strip, I wanted to be coherent. So every month I was drawing Jimbo and this girl having a living kind of relationship -- in a weird place, in the same place, Dal Tokyo, but since it became domestic and I didn’t want bad things to happen to them, it became pretty much like a married couple: “What are we going to eat today, honey?” So they can go eat something weird, but they’re still talking about boots and stuff. So it’d be good to have a break from it. Maybe I’ll go back to it some day.

SENECA: Do you ever feel you’ll need a break from Jimbo? I mean this has been your guy for decades…

PANTER: Yeah, Jimbo’s weird. Because when I first saw him, I thought, “Wow! This is something that’s going to be good.” But I never thought it would be the dominant thing I draw, and I don’t necessarily think it’s a good idea to do that. Who really wants to read about a redheaded guy in a loincloth walking around with short people, you know? It’s like… it’s Joe Palooka in some ways, and I wasn’t really a Joe Palooka fan. It’s what I found myself doing, and I keep getting ideas for it. And no one said, “Jesus Christ, stop,” no one’s said that to me yet. But when they do, I might listen.

SENECA: What keeps Jimbo interesting for you?

PANTER: Well, the reason he can be Dante is because he’s an observer; he’s an observer of complicated systems that have some story to tell. And I really liked, as a child, playsets. Playsets was my thing. I had all kinds of them, mainly the Ben-Hur set, but I had four of them. This is like that. It’s like playing with toys. My basement is packed with toys, I don’t really go play with them, but that state of mind is still going on. It’d be fun for me if I made little guys this big of all my characters and buildings and stuff, I’d be in some kind of sick heaven. Luckily, it hasn’t happened, so I can just keep drawing them.

SENECA: I would buy those.

PANTER: Yeah, I probably would too. [Laughter.]

SENECA: Do you feel, at this point, that Jimbo is just a vehicle, and it’s not as much about him as his observations?

PANTER: No, it is about him. I believe in him. He’s a real person, in some sense. All these characters are real to me, and I’ve started them up and they have attributes and I know how they behave relative to each other. You know, there’s probably a superstitious level to all this, which is trying to defer death and stuff by some kind of ritualistic sort of thing. There’s probably all kinds of things going on -- like, why are we doing these things? I wanted girls to pay attention to me. I wanted my father to pay attention to me. And I wanted to be famous, I wanted to accomplish something, I wanted to make a living, I want, I want… and all those goofy tracks are playing out, you know? You don’t really get a choice. You have to pay the rent and you have to eat and you have to sleep and find your way. This is a stupid way to try to do it. Being an artist is crazy.

And people -- the sad thing is, people write me every day, but once a month: “How can I have a career in comics?” and I just -- is there such a thing? I haven’t really experienced it. Maybe four thousand people buy my books. You can’t live from that. That’s crazy. If I can sell the originals, if I can design tennis shoes or whatever -- sell paintings -- then I can go ahead.

Transcribed by Ao Meng, Sam Chattin, Hans Anderson, and Matt Seneca