Joe Casey has spent his decades long career as a writer for comics carving an imaginative space for himself inside of corporate work — he’s done extended runs on X-Men, Superman, and WildC.A.T.s, as well as multiple other licensed properties. He’s built a body of original comics work and an co-created Ben 10 for the Cartoon Network. Ian MacEwan is early in his career but has already established a distinctive style in The Yankee, and in illustration work for companies like Arrow Video.

Joe Casey has spent his decades long career as a writer for comics carving an imaginative space for himself inside of corporate work — he’s done extended runs on X-Men, Superman, and WildC.A.T.s, as well as multiple other licensed properties. He’s built a body of original comics work and an co-created Ben 10 for the Cartoon Network. Ian MacEwan is early in his career but has already established a distinctive style in The Yankee, and in illustration work for companies like Arrow Video.

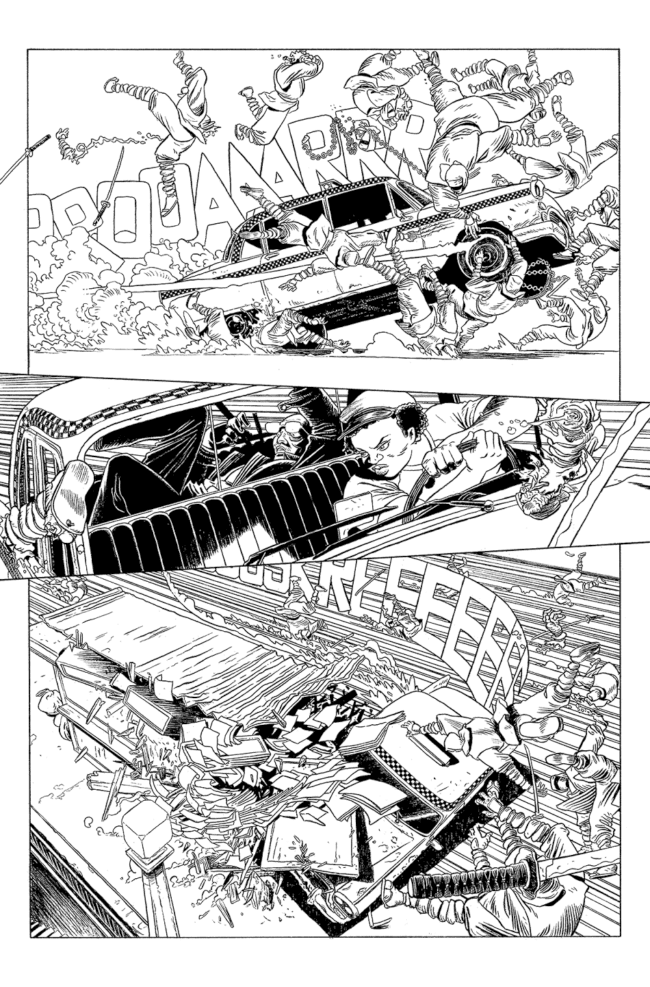

Casey and MacEwan are working together on MCMLXXV, a '70s period-piece fight comic born out of the imagery of exploitation movies and out-of-vogue action comics styles. MCMLXXV continues Casey’s trend of characters who are forced to meet the edge of their own understanding of the world. Casey often swerves on genre payoff without ignoring the pleasures and demands of adventure comics, and this new series is no different.

- - - - -

Sean Witzke: What led you to work on this project? I know you’ve are someone who has avoided being a career penciler for hire, can you tell me about your decision making process?

Sean Witzke: What led you to work on this project? I know you’ve are someone who has avoided being a career penciler for hire, can you tell me about your decision making process?

Ian MacEwan: Yeah, I've fought with the idea of being a work for hire artist for a long time, always leaning towards no. I've done it a little, with mixed results, and had one genuinely bad experience that left me wanting to not do it again. But I don't think that will ever be a blind no to anything I'm offered, and my time working with Joe on SEX was a positive one. So an offer from him to create something together appealed to me. The biggest thing was that I'd get a chance to draw a big knock down fight book, which I was itching to do. I wanted to know what that would look like. Books like that leave a lot for the artist to do, and it felt like the right challenge at the right time. I needed to get thrown in the deep end and do lots of things I hadn't done before, and I got what I wanted.

Can you talk about fight comics? Because I think I understand that means something beyond the "page 3-5 fight scene" style of writing, but you've been talking about doing something with long fight scenes for as long as I've known you, and you're not going to approach material with the same visual vocabulary as anyone on another Image book.

MacEwan: By fight comics I mean pretty much anything where fighting is the showcase of the book, the reason you come to it. Books where the lion's share of the story development aims to build weight around inevitable conflicts, even probe the reasons for them, but still come down to what's essentially a series of violent dance numbers. Something like Lone Wolf and Cub, which loves to obsess over specific cultural traditions and long bouts of nature gazing: every moment of its 8,000+ pages seethes with violence. Some superhero comics become fight books depending on the creative team, like Miller's Daredevil. I think plenty of sports manga fall into this box too. I mean, they're stories entirely revolving around physical confrontation, right? And in a way that most superhero books don't do, because they're more interested in soap opera. And soap opera can be great, but superhero comics tend not to feel like fight comics to me. They lack a certain "earned" quality with its characters, whose abilities came to them by dumb luck. I love when characters obsess over whatever it is they do best, and fighting just lends itself very easily to that type of story. They usually have more simplified plots, which is fine by me, because the familiarity with a plot that comes down to competition or revenge or whatever, works as a safety net to let a cartoonist focus on tone and smaller personal elements. Which is true for genre in general really, the tropes give readers something to immediately recognize so that the artist can play with tone, pacing, perspective, all that. So when that's applied to fight comics, they become showcases for an artist to speak and tell a story through linework and layout, and can get really personal in ways that still surprise me. Back to Lone Wolf: those fights are insane, sometimes incomprehensibly so. They're eruptions of fury, and their lack of spatial clarity loses importance and can become just abstract spontaneous brush strokes. And they work and become beautiful and that's all down to Goseki Kojima doing it page after page like a machine. Or someone like John Romita Jr, the way he breaks down forms into his blocky shorthand is so fun and sharp. It feels automatic. Or old Jademan comics, which I love, and plays with seemingly endless phantom images from a single swing of a weapon.

Jademan feels like it's completely been forgotten as a type of comic, they're really unlike any other mode of comics storytelling. It's one of those things that feels like someone came up with it independent of influence.

Jademan feels like it's completely been forgotten as a type of comic, they're really unlike any other mode of comics storytelling. It's one of those things that feels like someone came up with it independent of influence.

MacEwan: Those art teams put so much effort into the smallest details, and in so many styles. It's bewildering how panels switch from line art to fully painted to elaborate color holds that turn into abstract color explosions. I love the use of speed lines as active foreground elements. And blending that with all the phantom strikes, it loses any sense of space but makes up for it in sheer roller coaster ride. It's really effective at capturing a martial arts fight a the way that interprets long-take kung fu film fights. And wuxia is such a distinct fantasy genre, with each move having a name and discipline and celestial correspondence.

The production of those books too are just nuts, I loved how the back of each issue were full of pictures of artists working in the Jademan "bullpen" at their super specific art jobs. And above it all there's "Tony" Wong Fuk-Long always posing in expensive suits in front of his Lamborghini. He's more Hong Kong comics' answer to Phil Spector than Stan Lee. He's written multiple books about his own greatness, and gone to prison more than once for defrauding his company and his employees. And he's spent the last few years trying to build a billion dollar Hong Kong Comics amusement park!

What do you think the progression in your style has been since The Yankee? Has anything become easier to achieve on the page? Is there anything you are still struggling with conveying?

What do you think the progression in your style has been since The Yankee? Has anything become easier to achieve on the page? Is there anything you are still struggling with conveying?

MacEwan: The Yankee was the book I learned to ink with a brush on. I still predominantly use a brush, but I've gotten a lot more spontaneous. I don't treat it like it's a pen anymore. With this book, I use a lot of drybrush, something that was VERY new for me. It's not something I would have been able to do a few years ago, the lack of applying precise pressure and the sort of freestyling way that it's used would've given me a panic attack back then. I've gotten more into backgrounds too, sometimes to my detriment, as I wind up troubleshooting panels by making them harder on the drafting end of things. No one needs that many three-point perspectives in their comic! Overall, I feel more confident in my layouts and my rendering, I can light a composition much better, and I see my influences in my pages much less than I used to. In the past I would always worry that my lines look too much like someone else's, but I think (I hope) that's subsided quite a bit.

I struggle with my faces staying on model sometimes. I also have a reflex to want to design my pages as if they're going to be b&w. I've been trying to stay conscious of this, to allow more room for color to do the work, but I have to remind myself constantly, especially when I'm not doing the coloring. MCMLXXV is a bad example of that, though it was a deliberate choice to render things so dark. I made a rule that no night sky would be black, to let Brad take care of that, and that helped me to focus on grimy wall textures for contrast. But still, it's hard to keep in mind. A part of me wants a b&w page to be a complete object unto itself.

How do you feel about developing a body of work? I know Moebius is an immense influence on you, and I feel like (for a variety of reasons) people have a very thin sliver of his career in their perception of him, never the whole thing. I know it takes decades to build something with that depth, but do you have that in the back of your mind when you take on a new project?

How do you feel about developing a body of work? I know Moebius is an immense influence on you, and I feel like (for a variety of reasons) people have a very thin sliver of his career in their perception of him, never the whole thing. I know it takes decades to build something with that depth, but do you have that in the back of your mind when you take on a new project?

MacEwan: I've been thinking a lot about that lately. Or, what a body of work is has changed for me, it's less about genre and more about tone and texture. I had a bad experience on a work for hire project a few years ago, that made me rethink how I wanted to exist in comics, and I'm working toward getting there with each project now. MCMLXVV helped lay that out for me, and my next few books are going to lean more into exactly what I would want to see on my table at a convention. And, though I wouldn't claim to be able to compartmentalize to the intense degree that Moebius does, I've been sketching in different styles for each project. Among everything else, Moebius' versatility is the most astounding thing about him. The Yankee, The Azimuth Job (backups for Prophet), and MCMLXXV all look different to me, and feel like a decent start to a body of work I want to see. All self-deprecation aside regarding my satisfaction with my own work, they are books I want to exist.

I want to ask you about different approaches to different comics. To me, it feels like you are switching modes project to project and this new book feels like it's going for kinetic first, where the narrative serves those scenes. Sometimes in other projects I feel like the concepts are driving the story. Do you approach stories with that in mind?

I want to ask you about different approaches to different comics. To me, it feels like you are switching modes project to project and this new book feels like it's going for kinetic first, where the narrative serves those scenes. Sometimes in other projects I feel like the concepts are driving the story. Do you approach stories with that in mind?

Joe Casey: Oftentimes, yeah. Each book is specifically constructed to contain its own, unique set of challenges. Sounds nice and pretentious, doesn’t it? The things we’ll say to make our lives sound interesting! Anyway, I like all kinds of comics, so I don't know why I'd be content just making only one kind, in only one genre, employing only one approach. Besides that... I've been involved in comics for so long, it's rare that just reading comics gives me the same electric charge, the kind of visceral experience I would have before I turned pro. It can still happen, but not often. Now, don't get me wrong... that's not as cynical as it sounds. It's actually a reality that I'm perfectly fine with. I put myself in this place and I did it deliberately. I desperately wanted to know how the sausage was made and making comics professionally for the past twenty years certainly accomplished that. So if I can't have it when I read comics, I still want to have some kind of visceral experience when I make comics, so switching things up from project to project is one way for me to do try and do that.

When you're switching up, what tools are you using for this project? Collaborating with Ian on a fight comic or a 70s period piece is a different beast than someone with a more traditional approach. His pages feels more of the form instead of the flat, easy to guided-read on the iPad, style that's prevalent right now. Did you have him in mind for this? Develop it with him?

Casey: Well, let's see... I had the idea first, the basic concept. A sense of the potential iconography of the thing. Then I worked on the characters, the story, etc. for a good while on my own. I like to keep things in the so-called "mystery box" for as long as possible. That's often the most creative time for me personally; there's no pressure, no judgments, no deadlines, just pure imagination. Believe me, I’ve wrestled that deadline beast to the ground enough times… I prefer to avoid that fight, if I can help it. Eventually, things get to a point where I think I'm ready to bring in an artist. In the case of MCMLXXV, I'd worked with Ian on a fill-in issue of SEX so I already had a good sense of his strengths. It was pretty clear to me that he'd be perfect for this. Luckily, when I discussed it with him, he agreed with me. From there, he just started sketching. Luckily, I think we were on the same page from the start. Once we dialed in Pamela Evans' look -- which was, for me, the most important element of the whole thing -- Ian got started on the various gangs and monsters. That kind of stuff is just pure fun. It's where the scratch-mix mentality really finds expression, and we both indulge in all our various influences, most of which you can probably see right there on the page.

That scratch-mix mentality, to me that's been an element in your work that's shifted over time. I think over time, it felt like you started off playing with elements and then around Automatic Kafka there's a more pointed, rhetorical aspect to your work. The sustained relationship to Jack Kirby's work you have since you and Ladronn were doing to Cable all the way up to MCMLXXV has never just been a toy you were playing with as much as an interrogation. Is that considered or are you just consistently drawn back to that subject?

That scratch-mix mentality, to me that's been an element in your work that's shifted over time. I think over time, it felt like you started off playing with elements and then around Automatic Kafka there's a more pointed, rhetorical aspect to your work. The sustained relationship to Jack Kirby's work you have since you and Ladronn were doing to Cable all the way up to MCMLXXV has never just been a toy you were playing with as much as an interrogation. Is that considered or are you just consistently drawn back to that subject?

Casey: I'd like to think a lot of things have shifted over time. Even my relationship with my own influences has morphed and changed as I've been able to explore them through my work. And that's all any of this stuff is, really... an exploration. Of what, exactly, I'm not always sure. I'm one of those sick bastards where anything I've seen, read, heard, etc. that's somehow embedded itself in my subconscious… I take that shit very seriously. Probably too seriously for my own good, at times. But if something has stuck with me and actually influenced me creatively in some way, I don't ever take it for granted. The Kirby thing... aside from some of the formalist things I've explored in relation to his work, there's just an overall ethos that he represents that I've always gravitated to. The way he made comic books, there were no limits. He never seemed to close himself off from anything. And he never held anything back. He put it all out on the page. For me, that's always been something to strive for.

As a reader, it sometimes feels like you're using Kirby as an idiom to tell very un-Kirby stories. Like the visual language is there but I feel you bristling at the way he presented ideas, the way De Palma and Chabrol did very un-Hitchock movies in his idiom. I have wondered how he would react to it, as opposed to the way he dismissed anyone working on Fantastic Four or whatever in "the Kirby tradition" as missing the point.

Casey: Well, I'm obviously a very different writer than Kirby was. Actually, no one writes like Kirby did. I'm fundamentally a lot less primal a creator than Kirby was. Again, who is as primal as Kirby was? No one I can think of. But you're right... Kirby's true message was always, "Do your own thing". I've tried to follow that as best I can. But on the other hand, I'm such a student of the medium that there are times when I can't help but occasionally immerse myself in an idiom, a style or an approach and really try to somehow work through it in my own work. It's like I find a field of study and I really get into it. I liken it to someone like Tarantino, who'll apparently do a deep dive into a particular film genre -- the Western, the heist movie, the slasher flick, the WWII/Men-On-A-Mission movie -- and study what's out there, the good and the bad, and come up with his own take on it. I do the same thing, although it's with funky shit like the Moench/Gulacy/Day Master Of Kung Fu or the Baron/Guice Flash or late '70s David Michelinie or the Pekar/Crumb collaborations or Power Records' 1970s "Book and Record" releases or Jim Shooter's early work on Legion of Super-Heroes. I think it's a perfectly valid method of making Art. It's also a lot of fun. I still do it to this day, although I think I mined my particular Kirby fascination for all it was worth a few years ago and am on to other things (as the above list probably suggests).

Casey: Well, I'm obviously a very different writer than Kirby was. Actually, no one writes like Kirby did. I'm fundamentally a lot less primal a creator than Kirby was. Again, who is as primal as Kirby was? No one I can think of. But you're right... Kirby's true message was always, "Do your own thing". I've tried to follow that as best I can. But on the other hand, I'm such a student of the medium that there are times when I can't help but occasionally immerse myself in an idiom, a style or an approach and really try to somehow work through it in my own work. It's like I find a field of study and I really get into it. I liken it to someone like Tarantino, who'll apparently do a deep dive into a particular film genre -- the Western, the heist movie, the slasher flick, the WWII/Men-On-A-Mission movie -- and study what's out there, the good and the bad, and come up with his own take on it. I do the same thing, although it's with funky shit like the Moench/Gulacy/Day Master Of Kung Fu or the Baron/Guice Flash or late '70s David Michelinie or the Pekar/Crumb collaborations or Power Records' 1970s "Book and Record" releases or Jim Shooter's early work on Legion of Super-Heroes. I think it's a perfectly valid method of making Art. It's also a lot of fun. I still do it to this day, although I think I mined my particular Kirby fascination for all it was worth a few years ago and am on to other things (as the above list probably suggests).

It's an incredibly valid way of making art, I think it requires an investment like you're describing -- you can't just skim the best and play the hits, you have to have a fluency that a lot of people just don't want to dedicate the time to. Now, when I look at Ian's art I wouldn’t immediately go to Gulacy but your first issue has so much of that feel, of the way fights build... that era of Master of Kung Fu really figured out how to be kinetic and incorporate exploitation poster design, which is almost what Ian has arrived at from a different angle. Moench and Gulacy also felt free to steal what was in the culture -- Bruce Lee, 007, Emma Peel -- and run with them the way that's almost contemporary. Do you think making the book a period piece makes it feel more open?

Casey: It can be. Period is just another tool in the toolbox, another element of the overall story delivery system. As far as influences go, these things should always be properly subsumed into the greater whole. That's the idea, anyway. But it is a bit of a cultural grab bag. Personally, I think readers are going to respond to Ian's art because it's fairly fresh. He doesn't have a lot of published work out there, so no one feels like they've been beaten over the head by his art, enough to get sick of it. That happens more often than not.

Do you feel like that's happened to artists you've worked with before? Hurt projects you had different aims for?

Casey: It hasn't really happened to me all that much, because I don't think I've worked with any of the more ubiquitous artists that are out there. And that's not to say they're not great artists, because they are. But in mainstream comics, familiarity always ends up breeding some level of contempt. That’s generally how fandom works. Now, I've certainly had projects that didn't quite pan out artistically in the manner I'd hoped they would. But that's just how it goes sometimes. Besides, you can learn a helluva lot more from the times when you're not entirely successful than you can from the times when you are.

What do you feel like is the biggest lesson you've picked up from those times where you've met with an artistic failure? Commercially, that's always going to be an out of your control thing, no matter what you bring to the table; but, artistically, that's alchemy. How do you learn from that experience? At what point in a collaboration do you feel like you can gauge how well it's going?

What do you feel like is the biggest lesson you've picked up from those times where you've met with an artistic failure? Commercially, that's always going to be an out of your control thing, no matter what you bring to the table; but, artistically, that's alchemy. How do you learn from that experience? At what point in a collaboration do you feel like you can gauge how well it's going?

Casey: Well, that's actually a tough question, because each and every project contains a thousand tiny failures... as well as a thousand tiny successes. In terms of how I assess a collaboration as it's happening, it's kind of the same thing. They're both joyous and torturous at the same time. That's just the process. I'm sure my collaborators would agree. And when I say "collaborators," I'm including everyone on the creative team. In my case, I usually work with the same good folks, other than the artist. Lettering, colors and graphic design are almost always Rus Wooton, Brad Simpson, and Sonia Harris. I put them through hell and they put me through hell. But believe me, that's not a pejorative statement. I don't think making comic books is supposed to be a particularly easy process. Why would it be? That doesn't mean it's not great fun, but we're all in the foxhole together. If you're reaching for some form of greatness, it should be difficult. But, again, that's pretty much the only way to learn anything.

In developing that production team approach, is that just for ease of communication? And the idea that it's meant to be difficult to be great, how much do you feel like that's your own desire to create an environment that you need to produce at the quality you want? That's not a judgement call, because that's setting yourself up to create, but you hear stories of creative people who need to be at war with their collaborators to function, like Sam Peckinpah.

Casey: Well, first of all, let's be clear about something... when I work with any of my creative collaborators, I don't ever go the Peckinpah route. I look at it like we're all fighting the same war together. No one's ever deliberately trying to cause trouble for anyone else on the team. Believe me, life's far too short to waste time going down that particular road. I guess what I'm saying is that the difficult times are, creatively, nothing to fear. Not everything is an easy birth. Nor should it be. Different projects engender different experiences. All of them are valid, as far as I'm concerned. Now, having said that... are there times where I make it more difficult for myself in the writing process? Definitely. And, in those instances, I am looking to produce some particular, desired effect. But I try not to carry that over into other areas of the process, if I can help it. And I usually can.

So making things difficult for a desired effect, are you placing restrictions on yourself at a certain point in the process? What is the most useful headspace for you in developing a new idea?

Casey: I think the best lesson I've learned over the last twenty years is to hold onto certain things -- for myself -- as long as possible. To be patient with myself and my ideas. In other words, there are creators out there, especially in the class that I came up with, that would tend to succumb to some pathological need to talk about everything publicly and announce projects way too soon. Oftentimes, before they were even written. Aside from the fact that there were many times when those announced projects never saw the light of day, which is slightly embarrassing in and of itself... my feeling is that, the moment an idea escapes into the wild, the moment when that idea is shared with anyone, but especially with an audience you intend to eventually sell it to, it loses some of its juice. Before that happens, it's a very special period of time when it's just me and the idea and no deadlines or pressure to talk about it with anyone else. I’ve discovered that it's the most creatively productive time for me, so I protect that for as long as possible. Even when I do bring other collaborators in, I generally don't announce things until they're pretty much done. Now, that can mean that I'll end up working for years on things. MCMLXXV was about four years in the making. NEW LIEUTENANTS OF METAL, same thing. I've long gotten over the buzz -- if you can call it that -- of being part of the comic book mainstream zeitgeist and its attendant press demands, so I don't feel the need to constantly be interacting with the audience and keeping them informed of what I’m up to. It's why I'm not on social media. Ultimately, for the particular audience I’ve always tried to cultivate (whoever they might be), I've always believed it's about the finished work... it's not about that same audience riding shotgun with my ego as I'm making it. And it's ironic, because I'll fully admit I'm a huge process junkie. I love hearing about it. But I guess that love doesn't include my process.

It's interesting you say that because as a baby process junkie, reading the Basement Tapes felt like seeing what the fully formed version of it as a part of a creative drive. You've straddled a few eras in American comics, and one of those was comics-writer-as-cult-of-personality, which you seem to have parted ways with as a persona. That feels different than the process of building a brand via social media, which feels like it's its own monster. Of that group it feels like you've avoided some of the more embarrassing aspects -- becoming a company mouthpiece or writing movie pitch comics or flaking on entire series -- do you think that because you have success outside of comics that you can treat comics as their own reward? Or at least make them without other motives? 4 years of development on a series feels like the final goal must be the comic.

It's interesting you say that because as a baby process junkie, reading the Basement Tapes felt like seeing what the fully formed version of it as a part of a creative drive. You've straddled a few eras in American comics, and one of those was comics-writer-as-cult-of-personality, which you seem to have parted ways with as a persona. That feels different than the process of building a brand via social media, which feels like it's its own monster. Of that group it feels like you've avoided some of the more embarrassing aspects -- becoming a company mouthpiece or writing movie pitch comics or flaking on entire series -- do you think that because you have success outside of comics that you can treat comics as their own reward? Or at least make them without other motives? 4 years of development on a series feels like the final goal must be the comic.

Casey: I suppose this nebulous concept of “career diversification” turned out to be the key to any kind of comics longevity for me. After all, I'm well past the point where I need comics to love me back, if you catch my drift. And that's a very good thing for me, personally. I'd rather love comics unconditionally and expect nothing in return. That feels more pure. Certainly much healthier than the inverse. Now, I'll fully admit... as much of that diversification happened by accident as it did by design. But it did happen and when it comes to how I make comics now, I do my best to take full advantage of it. I know I'm incredibly lucky in that regard, but I also know that I bust my ass to try and make my own luck. Besides, that writer-driven era of mainstream comics you mentioned -- which I absolutely benefited from while it was happening -- seems like a lifetime ago now... aside from seeing those occasional, misguided souls who conduct themselves as though we were still in it. We're not.

With that perspective, do you still feel like some of your work is more personal? In those Basement Tapes columns, you mention several times that certain books have "Automatic Kafka in them", which I took to mean written with more of your voice than anything else. Kafka, Friedrich Nickelhead in G0dland and Zodiac felt like not writer stand-in characters, but figures that could say things with more frankness and awareness than was afforded other characters. Is that a tool for you to find your way to say more in certain stories? What does a personal project look like for you if they're all love letters?

Casey: I'd have to say that, at this point, there's a personal aspect to all my creator-owned work. To what degree… well, that varies from project to project. Oddly enough, I think the occasional "mouthpiece" characters I write tend to appear in my more mainstream, WFH comics. I just think it’s more subversive to do it when I’m getting paid. And paid well. But, more to your point, what Automatic Kafka specifically did for my work was give me a path to travel. A direction to go in. It demonstrated to me that I should have less of a filter between my own subconscious and what I actually put on the page. Trying to push the boundaries of my own creativity and putting those results -- whatever they might be at the time -- in the actual comics. That tends to make everything more personal.

Did removing that filter to your subconscious have a permanent shift or is that something you have to consciously return to in your work?

Casey: I suppose that would depend on what's going on in my life at any given time. So, in that respect, it is a somewhat conscious choice. It's not like I went to some strange Swiss clinic to undergo a permanent "filter removal." I guess I look at it more like an important tool in the toolbox... that ability to unleash my own imagination, spin it like a top and see where it goes. Again, pretension reigns! I do think that, every time I do it, I'm giving myself the opportunity to push myself further and further into uncharted territory. At least, uncharted by me. I've obviously never claimed to be the most original comic book creator out there. Far from it, but at least I can stand behind my work as coming from a genuinely pure place. To me, that's something.

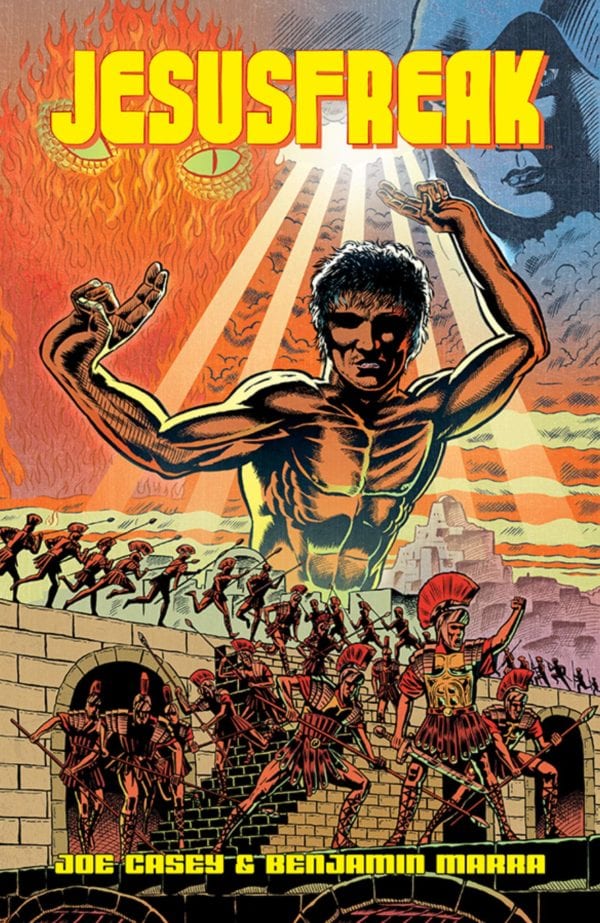

So you've just announced a new collaboration with Ben Marra, Jesusfreak, which is an adaptation of the Jesus narrative. Marra's work has been a similar approach to genre but with an entirely different tone. Marra's part of a group of cartoonists has been making, for lack of a better phrase, "arthouse action" outside of the direct market. What made you want to work with Marra?

So you've just announced a new collaboration with Ben Marra, Jesusfreak, which is an adaptation of the Jesus narrative. Marra's work has been a similar approach to genre but with an entirely different tone. Marra's part of a group of cartoonists has been making, for lack of a better phrase, "arthouse action" outside of the direct market. What made you want to work with Marra?

Casey: Marra and I have been friends for a few years now, but even before I knew him personally, I knew he was a kindred spirit. Ever since I saw original issues of Night Business out in the wild, I've been way into his work. Oddly enough, he and I have a lot of common influences, and it was just a matter of finding a project where we could both indulge in those influences in a very specific way. Marra's got a set of balls on him, too... which was needed to tackle this book.

What made you want to do a version of the Jesus story? Especially in 2018? Are you thinking provocation first? It's hard to top Robocop for ultraviolent Christ allegories.

Casey: Well, who in their right mind would even dare to try and top Robocop, right? For me, it's been a long road to get to this point, but this book was the kind of creative challenge that I knew would push me a little out of my comfort zone. It was a research-intensive project, which I liked. It leans a little toward the "literary" side of comic books, hopefully without sliding into the swamps of full-on pretension. Blah, blah, blah... all those meaningless reasons that artists make art. It is, as you say, a bit of an "arthouse action" book, but the subject matter automatically brings with it a layer of subtext that I found really interesting. The "provocation" part of it all... I'm not sure I have an answer for that. Because at the end of the day, when this thing comes out, I honestly have no idea what anyone's going to make of it. I can tell you that both Marra and I took it very seriously. This is not us just having a laugh... this is a couple of years out of our lives making this book. I do think all art should be provocative in some fashion, but I'm way too deep into my career for something like this particular book to exist only on some random, punk rock level. For me, personally, it's got to go deeper than that.