One of Charles Forsman’s new books, I Am Not Okay With This, is about Sydney: a “boring fifteen-year-old white girl” who is struggling with the death of her father, feelings for her best friend, and frightening telekinetic powers. The other, Slasher, is about Christine: a woman who finds sex and death are “married together in her mind” and must kill to achieve satisfaction.

Forsman’s also known for the teenage dramas The End Of The Fucking World – the basis for a new TV show – and Celebrated Summer, as well as his '80s action extravaganza Revenger.

Does a minicomic like I Am Not Okay With This change when it’s collected into a book like this? Do you feel like it has to carry more weight?

The whole conceit behind doing the minicomic is that it takes a lot of the pressure off. It doesn’t feel like a big important graphic novel or something. When I originally started The End Of The Fucking World, my friend Max did a comic called Moose in that minicomic style. Very short. He sold it for a buck. I saw that, and was like “oh this is great”, because I was struggling with what to do next. It felt like the stakes were much lower and that freed me up to just have fun and not work like it had to be a great piece of art.

The idea of serialization had never really occurred to me before. When I started making comics, that was sort of gone for the alternative wing. Fantagraphics and D&Q had stopped printing floppies, and everyone that I was into was getting graphic novel deals with big New York publishers. I had to stumble into the idea of serialization, and I fell in love with it. I like getting stuff out there on a regular clip, and it’s nice to get feedback as opposed to just fighting with my mind for two years on a project.

Do you usually enjoy the process, or do you just like having something finished?

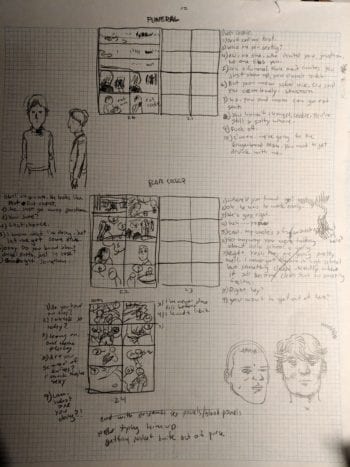

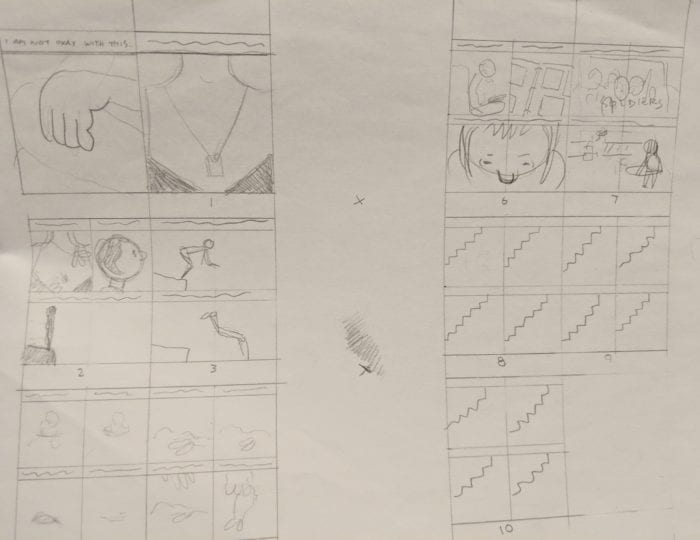

I do enjoy the process. My favorite part is the actual writing, the thumbnailing part, drawing my little tiny two-inch by one-inch thumbnails that I do for each page. I also really enjoy inking because it can be mindless work, sort of automatic. But I don’t draw for pleasure. I don’t keep a sketchbook anymore because I realized that was another thing I used to pressure myself about. All your friends constantly are doodling in sketchbooks like “this is what you’ve got to do!” It just felt like drawing for no purpose. I need a purpose, a story that I’m telling to get myself motivated. The drawing needs to be in service of something or I’m just bored.

Does that mean you need to think it’ll reach an audience for it to feel like it has a purpose?

I try not to think about audience because in the past that’s tripped me up. You sit there and try to think what kind of reaction people will get out of something you’re doing, but you never can. I’m more selfish and I like to just do it for myself. When I’ve done that, the reaction has always been better. I try to take confidence in that. When I’m enjoying the process, when I’m liking something, people are going to react to that. I hope that’s true going forward.

You often use teenage protagonists in your work. What’s so appealing about writing teens?

Yeah. It comes down to when I was a teenager. I was pretty depressed. I became disengaged from school and, you know, I got really cynical about life. I’m not special in this. The one big thing that happened was when I was 11, my dad died from cancer, and that was such a changing moment in my little world. It made me grow up a little faster: life is not always running around in the suburbs, riding bikes, and having fun.

There’s a part of me that wants to constantly relive that because when you’re a teenager your emotions are so raw. You think you have everything figured out, but you’re also so lost and frustrated. I just find it fascinating, and I’m trying to organize that time of my life on paper. Figuring out how to get it out, to communicate these feelings. Because it can be pretty complex, and I’m not the best speaker. Comics is how I’m most comfortable.

I Am Not Okay With This is usually very restrained. There’s no purple prose. You have a pivotal scene staged outside a parked car. Do you have to resist the urge to go for bigger, “louder” emotional moments?

For books like I Am Not Okay With This, I’m very inspired by the simple staging of old newspaper strips like Popeye. That’s the biggest influence most people see. I like exploring these complicated, emotional feelings in a style that’s not what you’d expect. And I like to leave a lot up to the reader. I need room for people’s interpretations, because everybody brings something to the work on their own. For me, that’s always the most enjoyable part of consuming work. How I interpret it, what I bring to it. I’m not a fan of spelling everything out, or explaining every little detail.

I was wondering about Sydney’s telekinetic powers in the book. What made you decide to use a fantastical element?

It’s a bunch of different things. I’ve been doing that book Revenger, and there’s nothing fantastical about that – except maybe future robots. That was me getting into the comics I was into as a kid and letting myself play. Dabbling in genre that I used to be afraid of, for whatever reason. For this book, I think that the idea came from watching Scanners for the first time, that Cronenberg movie. I hadn’t seen it until about four or five years ago. A lot of people say it’s basically a cool X-Men movie and I love that idea. What if I did my version of that Scanners, X-Men type thing and put it in a teenage girl? Quickly it became a manifestation of her anxiety. To me the book’s not so much about her having that power. It’s not even a “power”, really. It’s more something that’s crushing her, that she’s trying to figure out.

Speaking of Revenger: in the back of the first issue you say that you consciously tried to up your game when it came to the art. How did you approach “upping your game”?

I never felt like I had a style that was mine, and that used to really bug me. But now I see it as a strength – I’m not so afraid to draw in a completely different way than I had before, even if it’s hard and uncomfortable in the beginning. It can shift so much in service of the story. For an '80s action comic book, I had to do it in a different way. It just felt right.

I probably drew and redrew that first issue over a year. It took a lot for me to have the confidence to release it, but it’s been fun. It really opened my mind. I used to be afraid to draw on large paper, and those Revenger stories went up to 11" by 17" – whereas I Am Not Okay With This was drawn tiny, almost at the size it’s printed. It used to be I couldn’t handle a large sheet of paper. My mind couldn’t take it all in. It was hard for me to see the page when it was so big. So it was fun tricking myself into being able to work like that. And I’d never done an American-style comic book in that standard format. I used to shun that idea – but then I thought, what would happen if I worked within those constraints?

The End Of The Fucking World and Celebrated Summer feel like they’re made up of still moments, but Revenger is so full of motion.

That’s an interesting point. Revenger is all about me trying to do action. Which, like I said, I wasn’t comfortable doing, so I think you can see me learning on the page, hopefully getting better as the stories go. I do tend to like to slow down a lot in The End Of The Fucking World and I Am Not Okay With This and especially Celebrated Summer – that’s almost an experiment in slowing down time and taking in details.

You still slow down time in Revenger – it’s just to show a knife slowly plunging into an eyeball.

Well, that’s important. Does the reader really feel it unless I slow it down over eight panels?

There’s a rawness to your comics – and I know “rawness” is a strange term, because it can imply it’s underdeveloped or something – but how do you balance that sense of rawness with your craft?

I totally agree that my work is raw, and I feel like it’s a necessary thing for me. I mentioned my friend Max de Radiguès, and something he taught me a long time ago was to move forward and not dwell on the page. You can get stuck easily, and I certainly used to get stuck, worrying: “This just sucks, it can be better, everyone’s going to hate this…” There’s a huge value in learning to keep moving forward, and that the next page will be better than the last.

Revenger and Slasher – I’m putting more time into those pages, as opposed to something like I Am Not Okay With This. It’s very raw for me. I don’t do a lot of editing. I just plow through the pages. It’s a lot closer to what’s in my head, and that’s what I like about it. The End Of The Fucking World was like that too. There’s a lot of improv in there, moments I couldn’t have planned. It feels disingenuous for some reason for me to go back and change things, make it better, or whatever. Those zines are what I was doing, and I want to keep presenting them that way. For better or worse.

I just finished reading Slasher and it feels like a comic that I would have found in the woods as a kid and it would’ve freaked me out. Is that a compliment?

Sure! I’ve gotten some strange reactions to that book. A lot of good reactions – but most people say “Man, that’s sick. I love it.”

Slasher is the most explicit the connection between sex and violence has been in your comics, but it’s there in other work too…

Yeah, a little bit. But Slasher is putting it front and center. Those two subjects are something I write a lot about, so I thought: what if they were really close in the main character, Christine? What if those two things were married together in her mind, and she couldn’t separate them?

Was this a conscious attempt to push those subjects as far as you could? Or did the story drive itself in that direction?

It was, as these things go, a little bit of both. I wanted to do something psychosexual… my version of a Brian De Palma movie. I had a full outline written out but the second half of the story changed quite a bit from what I originally planned. I did want to push my own limits.

If you had to adjust your style for Revenger because it “just felt right”, how did you approach Slasher? What were your influences?

I saw Slasher, stylistically and subject-wise, as bridging the gap between the two modes I had been working in. I wanted to have it be a bit more realistic and not so cartoony feel but I really wanted it to still feel drawn. I was looking at a lot of José Muñoz’s Alack Sinner stories. That work has had a big influence on people like Keith Giffen, and Frank Miller’s Sin City. I wanted to wear that suit for a while. I’m still fascinated by it and will probably keep working in this mode on my next series but in black and white this time. Slasher was done in color so I was still having the colors do some heavy lifting. I’m excited to really let the ink fall on this next one.

You’re having an intense few months: two books, the Revenger Christmas special, and The End Of The Fucking World TV show! How does it feel?

It’s pouring. This happens sometimes when you make stuff. For whatever reason, this year was just like an avalanche of work coming out within a short period of time. It’s a bit crazy but I need all the attention I can get to make it through the coming winter.

But seriously, I’m very thankful to be able to have all this work out there. And the TV show has yet to hit most of the world but I can’t wait for everyone to see it. I didn’t work on it so I sort of feel like just another viewer – but I get goosebumps when I see a panel I’ve drawn recreated on the screen or hear a bit of my dialogue being said by an actor. It’s a strange feeling. Still not used to it.

What was it like watching your pencil and ink creations played by flesh and blood humans? Did it make you see new aspects of your own work?

I really enjoyed seeing what the writer, Charlie Covell, chose to expand to magnify the themes I had in there. I was quite jealous of some of the choices she made and stuff she added. I told her that I wished I’d thought of what she’d done with the story.

I try to keep in mind that my book is my book. It’s the only way I can be at peace with it. I think that was important for maintaining my sanity. They could have made a piece of shit… so I was conscious to remind myself that my book is still my book and that isn’t changing. I love movies and TV so it’s a real fucking thrill to see this stuff come alive. It’s exhilarating. I can see how one can get sucked into doing movies. It’s a charge to watch the crew and cast bring these ideas to life.

In the back of Slasher, you have reviews of old, “trashy” comics. What’s the appeal of those books for you?

Over the last three, four years, I got kind of burnt out on alternative comics and graphic novels. I started digging out my comics from when I was a kid. I was inspired by folks like Michel Fiffe and Ben Marra who were working in action and genre, plumbing from those comics they read as kids. I started finding the really weird stuff. Those self-published, one-off issues that someone did, probably worked months on in 1987. Printed it in black and white. Borrowed money from their uncle. Promised 30 issues but only did one. There’s an amazing passion in a lot of those works. You can almost equate it to what I did with The End Of The Fucking World. I wasn’t worrying about whether it was pretty, I wasn’t worrying about who was reading it…

I get a lot of inspiration from those books. I think they’re cool. I find it fun to look at young, immature artists and see how they figure things out. I identify a lot with that. I don’t consider myself a naturally talented artist. I feel like I have to work within whatever talent I have to create something that’s readable. So I like watching people work within their limitations.