Previously, the introduction, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, part seven, and part eight of our story.

IX. Joe and Abner

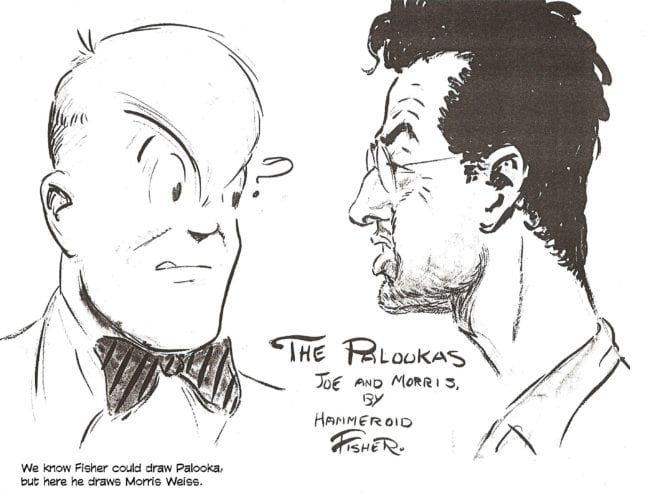

BUT IT WAS FISHER’S REPUTATION THAT WAS OBLITERATED. It is still bruited about among cartoonists, for instance, that he couldn’t draw. And I’ve seen evidence to the contrary — including photographs of him doing chalk talks at which it would be impossible to fake drawing ability.

Even if my bald-faced assertion is suspect — since I didn’t actually see Fisher draw the pictures attributed to him — the logic of the contention that he couldn’t draw is internally flawed. And the flaws reveal the falsity of the allegation. If he couldn’t draw, how could his colleagues determine he had doctored the panels from Li’l Abner? And if he couldn’t draw, the anecdote about the beautiful blonde wanting his autograph and being disappointed when she realized he wasn’t Al Capp is a fabrication: a key aspect of the story is Fisher drawing a picture of Joe Palooka right there, on the spot.

But Fisher simply disappeared, faded into the dimly recalled corridors of cartooning lore, his achievements becoming faint as they retreated into the darkening distant hallways of the past until, like Lewis Carroll’s famous grinning cat, only a shadow remains behind, albeit a substantial shadow — a 10-ton statue of Joe Palooka, carved in 1948 as part of the Indiana Limestone Centennial, remains in Bedford, Ind.

No one decided to deny Ham Fisher a place in the history of cartooning. The profession’s odd silence on the subject is not the result of deliberation and design. It is instead an accident, an unforeseen constellation of circumstances, a happenstance of personality and event, which, invested with pride and ego and jealousy and vaulting aspiration, turned ugly. The tragic end of the Fisher-Capp feud could well promote vague feelings of shame and guilt among those who stood by, feelings that were suppressed by keeping silent. Fisher’s suicide was a blot on the escutcheon of the National Cartoonists Society. And it is therefore understandable if many cartoonists fell into the habit of not mentioning it. And by avoiding the subject of Fisher’s death, the subject of his attainments is likewise shunted out of view.

While I’m delving into unconscious motivations, let me toy with one more fanciful speculation. This time, on the matter of Fisher’s motives.

Fisher’s behavior strikes me as more than a little extreme. Capp’s appropriation of hillbilly characters for a comic strip doesn’t seem to me sufficient provocation for Fisher’s subsequent actions — the tirades, the smear campaign. Psychologically speaking, when someone’s behavior is excessive for the provocation, it suggests that the presumed motivation is not, in fact, the real reason for the reaction we see. And when this happens, it’s because the real reason must not be consciously acknowledged.

Fisher accused Capp of stealing his hillbilly idea, but there is virtually no substantial similarity between Capp’s Yokums and the family of Big Leviticus in Fisher’s strip. Both families are hillbillies, and both are, by sophisticated big-city standards, stupid; but there the resemblance ends. The Yokums are absolutely good; Big Leviticus and his relatives are mean.

Fisher could scarcely claim Li’l Abner is Big Leviticus.

We could make the case that Big Leviticus and his family are reincarnated in Li’l Abner as the infamously depraved Scragg family. But with the Scraggs, Capp exceeded anything Fisher could have imagined. The Scraggs are absolutely amoral monsters, killing and maiming their way to their objectives, whatever they may be. Big Leviticus was mean, an all-purpose bully; but he wasn’t monstrous. Besides, Big Leviticus made only occasional appearances in Joe Palooka; and likewise, the Scraggs in Li’l Abner. Neither Leviticus nor the Scraggs were so conspicuous as to constitute the reason for either strip’s success. Both sets of characters were, in fact, minor figures in the casts of the two strips. In short, the Scraggs could not have been so constant a reminder as to be an ever-present irritant to Fisher. And Fisher’s behavior is that of a man constantly plagued with an annoyance that wouldn’t go away.

The explanation for his behavior, it seems to me, is this: On an unconscious level, Fisher didn’t believe Capp stole hillbillies from him; he believed Capp stole Joe Palooka.

The heroes of both comic strips are big, strong hulks and a little slow-witted. I don’t mean that Joe Palooka was ever as stupid as Li’l Abner. But the early Joe was so naive, so innocent of the world, that he seemed stupid. Like Li’l Abner, Joe came from a small-town environment in rural America. As in Capp’s strip, some of Joe’s earliest predicaments were caused by his innocent inability to understand the more sophisticated world in which he found himself. (Palooka’s first fight is a perfect example of exactly this aspect of his character.) Joe usually wins in these situations: His essential goodness triumphs, an affirmation of virtue.

In Li’l Abner, we have pure stupidity firmly ensconced in place of naive innocence. But the flywheel of the strip’s dynamic is the same: stupidity and innocence are interchangeable as plot devices. For all his stupidity, Li’l Abner is as fundamentally good as Joe Palooka; in fact, Abner could be seen as a parody of Palooka.

Capp’s satire unquestionably ridiculed everything that Fisher believed in — the triumph of virtue, goodness, purity, and wholesomeness. The good characters in Li’l Abner do not so much win as they simply survive. Mammy Yokum is the exception. When she becomes engaged, she wins. But the other Yokums are perpetual victims. They are resilient rather than victorious. They are good people, but they don’t survive by being virtuous as Joe Palooka does. They survive because the forces opposing them destroy themselves with conflicting venal motives.

The lesson of Fisher’s strip is that virtue will prevail. The lesson of Capp’s strip is that evil will prevail but that goodness will somehow survive. His strip was the cynical response to Fisher’s strip. Li’l Abner was almost a lampoon of Joe Palooka, as I said. But I don’t think Capp had gentle Joe in mind as a specific target. The target of Capp’s parody is all of misguided humankind, the people who believed in what Fisher believed in. No wonder Fisher was so continually enraged by Capp.

So why didn’t Fisher say that Capp stole Joe? Partly because on the conscious level, Fisher didn’t fully comprehend what he perceived on the unconscious level.

Partly because asserting the theft would proclaim the parody, making Fisher’s achievement overtly the butt of the joke. But there is more to it than that.

Eventually, Joe Palooka got smarter. By the end of the 1930s, he was an inspirational figure. He became more sophisticated. He lost his innocence. And in place of innocence, Fisher substituted goodness, pure and simple. If Fisher were to have claimed that Capp copied Joe Palooka in creating Li’l Abner, he would have reminded everyone that his Kindly Gracious Knight was once as naive as Li’l Abner was stupid. In fact, to all intents and purposes, Fisher would have been confessing that Joe Palooka was once a stupid hick. And that admission would have sullied the image Fisher had so carefully constructed for his champion.

And rather than risk undermining Joe’s image, Fisher shifted attention away from Joe and Li’l Abner to hillbillies in general. But he could not divert the vehemence of his outrage at Capp’s having stolen his hero in order to ridicule everything he believed in. And so the accusation about the theft of the hillbilly motif became unconsciously invested with psychic energy drawn from the real cause of Fisher’s anger, Capp’s parodic ridicule of Joe Palooka’s triumphant goodness.

That source of energy fueled Fisher’s rage until it became fuming hatred. And Fisher could incorporate into his personal motivation a larger, social mission. To the super-patriot Fisher, champion of traditional American values, Capp’s satirical crusade (not to mention his subliminal sexual innuendoes) seemed bent on corrupting conventional morality; Fisher had to stop it. And so, desperate, he resorted to the smear tactics that eventually led to his ouster from NCS and, perhaps, to his own death.

Fisher had demonstrated jealousy about rival characters very early in the run of Joe Palooka. Weiss told me of Fisher’s concern about Mickey Finn: “When I started working with Lank Leonard in 1936, it was the same syndicate as Joe Palooka, and Ham was rather upset at the syndicate’s taking on another character whose personality was similar to Palooka. Mickey Finn was a nice Irish cop, but very naive. Lank Leonard had to go in to get together in a conference with Ham and Charlie McAdam to make sure where he was going with Mickey Finn. Mickey Finn was going to be a wrestler at one time.”

Here Fisher revealed a conscious concern with roots in the competitive nature of the marketplace for comic strips; with Li’l Abner, if my speculation is accurate, his preoccupation had a much more insidious origin.

There was nothing furtive, however, about the attitudes of the two feuding cartoonists toward their creations. Capp always spoke disparagingly about Li’l Abner, habitually calling him a stupid lout. He seemed to have a very low opinion of his protagonist. On the other hand, Fisher admired Joe Palooka. He loved him. And Fisher had no other friends.