Previously, the introduction, part two, part three, part four, part five, and part six of our story.

VI. The Bitter End of Ham Fisher

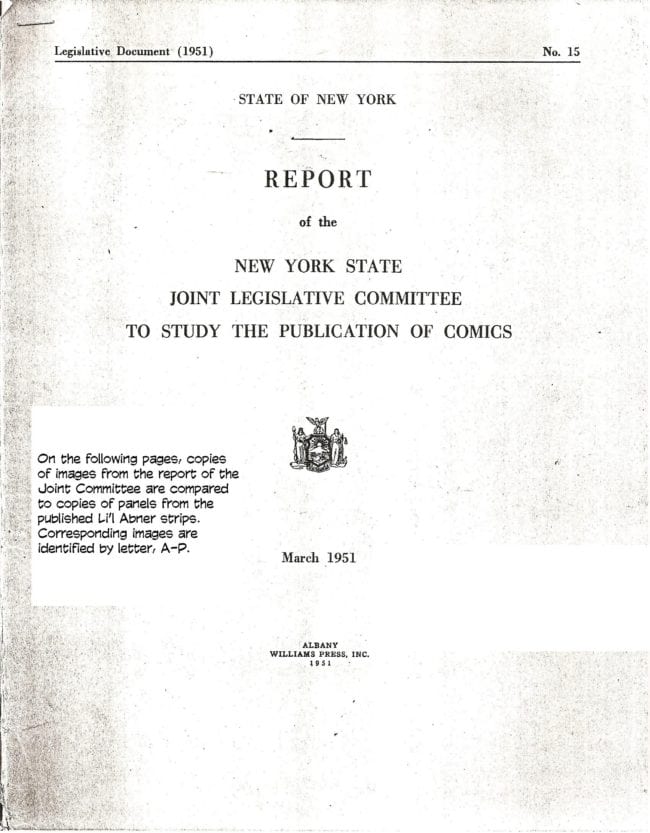

A FEW MONTHS LATER, blow-ups of Li’l Abner panels taken from their reprinted version in comic books, were submitted anonymously to the New York State Joint Legislative Committee for the Study of the Publication of Comics, a body charged with determining whether or not comics should be censored. The Committee’s subsequent report included the Abner artwork, examples of which we’ve posted nearby.

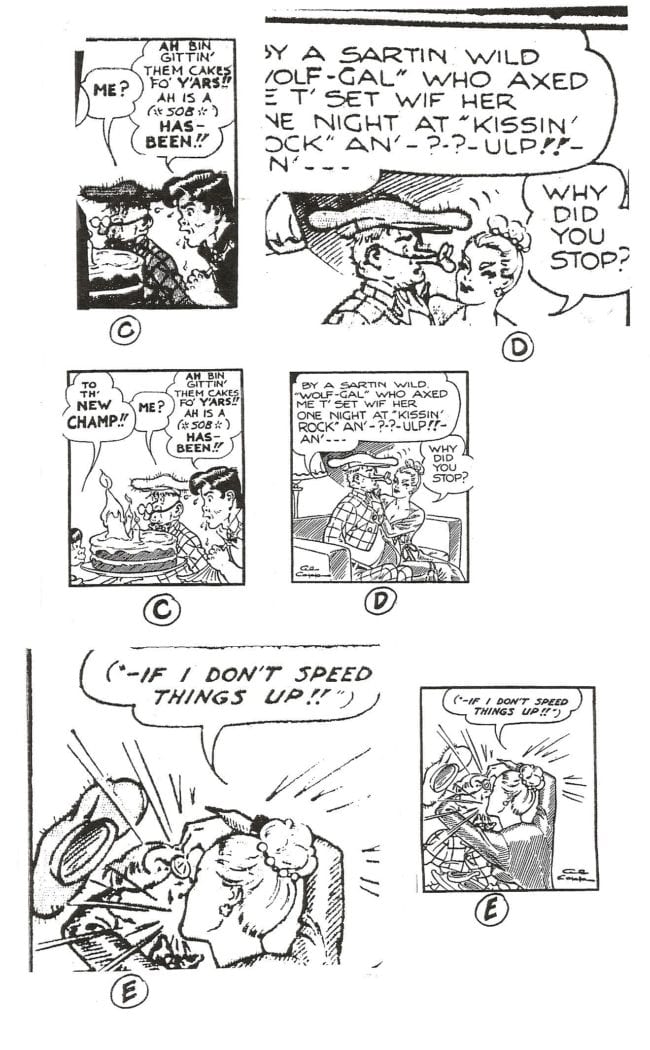

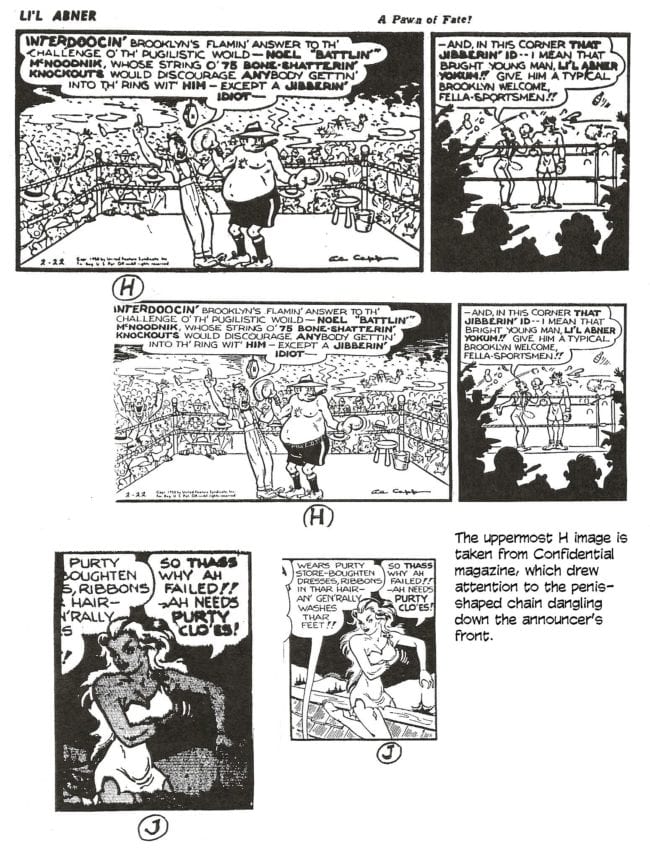

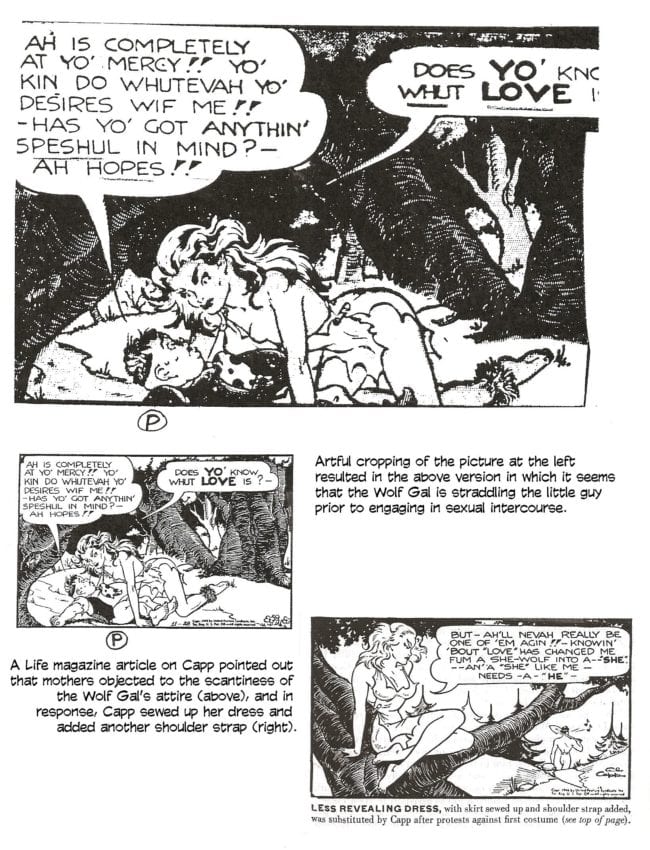

The examples are lettered, and each letter appears twice: once under the panels copied from the Committee report and once under corresponding panels copied from the Kitchen Sink reprints of the published comic strips. (The latter are the clearer images.) This comparison demonstrates that the dubious panels appeared in the nation’s newspapers not just in the Committee report. At the time of the report, however, no one (except Capp and his syndicate) had access to a supply of Li’l Abner as published; the comparison we’ve made here could not have been made then without making a considerable effort.

In several panels, the prominent nose of one citizen of Dogpatch had been extended to approximate the shape of a penis, and when he encounters a pretty girl, his nose stiffens. In one panel, another Dogpatcher and a female character are shown in a position approximating copulation.

Written in the margin of this drawing was this proclamation: “This insane, perverted pornography is from Li’l Abner, yes!!! This is what Al Capp has perpetrated for 15 years on unsuspecting editors of American newspapers!!!”

This was the incident that would seal poor Fisher’s fate.

It was assumed immediately that Fisher had given the pictures to the Joint Committee: They were, after all, of the same ilk as those he had been circulating to newspaper editors. A good deal of lore has accumulated about this episode in the history of the profession. The biggest pile of it is heaped up around the “doctored” drawings. It was claimed that they could not have been Capp’s work. Indeed, Fisher’s evidence itself seems to render his argument outlandish. The drawings are so blatantly suggestive as to trumpet their sexual double entendre. None of them, it must have been supposed at the time, could have slipped by an “unsuspecting” editor into print. Clearly, the drawings in possession of the Joint Committee were not Capp’s. Clearly, the panels from the initial newspaper appearance of Li’l Abner had been tampered with on their way to the comic-book reincarnation in evidence before the Joint Committee. Or so it would seem to any reasonable observer.

But whether the drawings were Capp’s or not, that question was moot: placing them before the Joint Committee created a crisis. Given the temper of the times (the McCarthy era had just dawned) and the growing criticism of the comic books (as being a cause of the postwar wave of juvenile delinquency that was sweeping the country) and the task assigned to the Joint Committee on Comics (to decide whether to censor comics), the situation was suddenly grave in the extreme. It was no longer a simple matter of someone’s having attacked Al Capp: This act of intemperate zealotry could result in the restriction of creative freedom for an entire profession.

Alex Raymond, who was then President of the Cartoonists Society, appeared before the Joint Committee and defended Capp, believing that the pornographic aspects of the strips could not have been Capp’s work. Several years later, on Jan. 6, 1955, Raymond would write to Capp about this incident, saying:

I am convinced, after seeing the photostats reproduced in the Report of the Joint Committee compared with the original drawings of Li’l Abner from which the photostats were made, that someone distorted, cropped, faked, wrongfully emphasized and twisted your material during the process of reproduction to make it appear pornographic. Such machinations could cause the work of any contemporary artist to appear erotic.

Back in June 1951, Raymond had summoned Fisher to appear before the Board of Governors of NCS for questioning. Morris Weiss said he talked to Raymond beforehand. “Raymond said, ‘Look, if he just comes and apologizes and says he did it, that’s all I want. I don’t want to have him thrown out of the Society.’ That’s what he told me at the time. And then of course, I told Ham: ‘You’re going to come down with me, and you’ll do this.’”

But when Fisher appeared, he vehemently denied having anything to do with the pornographic Li’l Abner panels. “I don’t think he ever admitted having doctored them,” Weiss told me.

Although the Joint Committee proposed legislation intended to impose “prepublication review” on the comic-book industry, none of the measures made it into law: In the spring of 1952, Governor Thomas E. Dewey vetoed the proposals as unconstitutional. But the potential for tragedy lingered on, even though Fisher and Capp now curbed their animosities.

Then in the fall of 1954, the affair erupted anew. A Boston communications company in which Capp had a small interest (reportedly less than two percent) applied to the Federal Communications Commission for a license to operate a television station. Reviewing the ensuing events in a February 26, 1955 article, Editor & Publisher reported that when the FCC held a hearing on the application, the 1951 report of the New York State Joint Committee studying the comics was anonymously introduced. The report, which contained the alleged pornographic drawings from Li’l Abner, was clearly intended to discredit the applicant’s fitness to operate a TV station because of Capp’s participation.

Capp denied that he had drawn the offending pictures, but he was nonetheless forced to withdraw his interest in the Massachusetts Bay Telecasters, Inc., in order to expedite the proceedings and to ensure the firm’s success in obtaining a license. Then Capp appealed again to the Cartoonists Society to do something about Fisher.

The matter was referred to the Ethics Committee, then chaired by Milton Caniff. Caniff’s friendship with Capp was deeply rooted in their fellowship during long evenings together in the AP bullpen. When Caniff saw the panels purporting to be from Li’l Abner, he wrote to Capp in high dudgeon on Dec. 4, 1954 (a letter Raymond had clearly seen when, a month later, he wrote his; see above):

Dear Al:

I was amazed yesterday when I had my first look at the photostats reproduced in the Report on the New York State Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication of the Comics (1951) placed beside the original drawings of Li’l Abner which the stats purported to represent. [Caniff doubtless did not compare the panels in the report to original drawings of Capp’s strip. Rather, he was acting on faith alone.]

There has been such obvious distortion, contraction and withdrawing from context that someone (clearly not connected with the Committee) has altered the material in an effort to cause mischief or worse.

Any cartoon strip can be done unto the way yours has been. Enough twisting, turning, photostating in black and white from color printing and the like machinations could reduce the work of any contemporary artist to what could seem a parade of eroticism.

In my opinion, this emasculation of your work hurts our entire profession and the client newspapers which publish our product.

In due course, the Ethics Committee voted to call Fisher to account for his conduct. Although there was no hard evidence to link Fisher to the alleged forgeries, the cartoonists decided after examining the drawings that Fisher had indeed been the person who had circulated them. Weiss said it was Fisher’s handwritten comments in the borders of the pictures that gave him away: “They saw that this was Ham’s handwriting.” Moreover, all the other surrounding circumstances led to a conclusion that Fisher had in fact done the dirty deed — the long-running feud, Fisher’s almost irrational animosity toward Capp, the episode of the annotated Li’l Abner strips that were circulated to editors a few years before, Fisher’s preoccupation with the alleged pornography in Capp’s work.

On Jan. 24, 1955, Fisher was summoned to a special meeting of the Society’s Board of Governors to hear the charges presented by the Ethics Committee. The Committee charged Fisher with doctoring the drawings and circulating the forgeries to discredit Capp — acts which had the effect of endangering the creative well-being of every other cartoonist. In submitting the drawings to the New York State Joint Committee on the Comics, Fisher had subjected the profession undeservedly to scrutiny by a body that was actively considering measures that would restrict every cartoonist’s freedom of expression. Fisher’s conduct, the Ethics Committee concluded, was “in violation of the entire spirit of the Society and the purposes for which it was established,” reflected “discredit upon the Society and the entire profession of cartooning,” and was “unbecoming a member of the Society.”

Fisher, who had come with counsel, took the advice of his lawyer: He said absolutely nothing as the charges were presented. Finally, Fisher’s lawyer said that they’d have to see the charges in writing before attempting to answer them. He and Fisher left, and the meeting broke up.

A letter setting forth the charges was composed forthwith. Fisher was accused of conducting himself in a manner that reflected discredit upon the Society by lying to the Board of Governors in June 1951, by circulating forged material, and by attempting to destroy the reputation of a fellow cartoonist, all of which risked governmental control of the profession. Fisher was ordered to appear to defend himself on Feb. 1. On that date, Fisher asked for a postponement, saying he was ill. But when he failed to appear at the rescheduled meeting, the Society acted on the basis of the Ethics Committee’s findings. On Feb. 9, 1955, NCS President Walt Kelly wrote Fisher with the news:

We have the unhappy duty to inform you that after due deliberation, the Board of Governors of the National Cartoonists Society has unanimously ruled that you are suspended from membership for conduct unbecoming a member. This suspension will remain in effect until such time as you appear to offer evidence which may change our minds. You have been given three opportunities and many hours of hearings to justify yourself. We are sorry that you have failed to do so.

Regretfully,

The Board of Governors

Unhappily, the news of Fisher’s suspension was leaked to Editor & Publisher, which announced it in its Feb. 26 issue, quoting from a letter Fisher had fired off in his own defense. He protested the “unseemly haste” of the Society’s action, saying that he was not given a chance to defend himself. “The Board of Governors ignored my request for a postponement of its hearing. At the time, I was seriously ill, under doctors’ care.”

He fulminated against Capp, defending the authenticity of the drawings that established Capp as a pornographer and charging that his suspension was “part of a scheme to whitewash Al Capp in behalf of his tv venture.” He claimed that it was “unmistakable” that the accusations against him were “completely fraudulent,” and he said that he had “new material which has just become available” that would vindicate him. He was confident, he concluded, that in the light of this new evidence, the Society would “reconsider its hasty and intemperate action.”

Fisher would never produce the new evidence. Perhaps there was no new evidence. Perhaps he intended to introduce an article that had run in Confidential magazine over a year before. In the November 1953 issue, Brad Shortell had written a cover story about “The Secret Sex Life of Li’l Abner” in which Capp’s “droll incursions into ruttishness” were described and illustrated with materials obtained from the Joint Committee’s 1951 report. Relying also upon Kahn’s two-part profile of Capp in The New Yorker (Nov. 29 and Dec. 6, 1947), Shortell claimed that Capp drew some of his strips for a “secret audience,” introducing into the panels images that verged upon the subliminal but that could be deciphered by Capp’s “inner circle,” which saw in the pictures the sexual allusions Capp intended.

In the first part of his profile, Kahn had described three audiences for Li’l Abner “corresponding to the three levels upon which [the strip] is constructed.” The first level is simple narrative; readers in this audience enjoy the story. The second level is satirical; readers delight in seeing Capp skewer social ills and political posturing.

The third level, sometimes of microscopic dimensions, consists of bits of Rabelaisian humor, often so adroitly covered up that, like rare archeological treasures, they are less likely to be spotted by children at play than by people who set out looking for them. These mischievous escapades in print amuse Capp more than anything else about his work, and the thought that few of his readers share this enjoyment with him depresses him. If, however, he were to make these touches more obvious, it is possible that his strip might be banned not only in Boston but in Springfield, Charlotte, and San Antonio as well.

While testifying during the FCC hearings, Capp had been asked about the “bits of Rabelaisian humor” that he had allegedly insinuated into his comic strip. In Time’s report on the hearings, Capp was “unruffled”: He said that both he and Kahn “were professional ‘humorists’ who used ‘exaggerated humor. The method of The New Yorker,’ he added, ‘is different from other magazines. Mr. Kahn simply listens; he does not take notes.’”

Questioned on the matter, Kahn snapped: “Of course I took notes, and I still have them.” For his part, Capp vehemently insisted that the pictures of “semi-hidden pornography” were forgeries.

In the aftermath of his explosion in Editor & Publisher, Fisher didn’t produce the Confidential article. He didn’t unearth Kahn’s New Yorker profile. Nor did he find a transcript of the FCC hearing. He didn’t produce anything in his defense. That Fisher could have defended himself at least against the charge of doctoring Capp’s work is entirely possible. Assertions to the contrary notwithstanding, it is highly probable — indeed, likely to the point of certainty — that the so-called pornographic panels from Li’l Abner are, as Fisher claimed, Capp’s work. Certainly most of them are. With the reprint volumes from Kitchen Sink Press at hand, I compared panels reproduced in the Joint Committee’s report with the panels in the strips as they had been first published. Wherever I found corresponding panels, they were identical. Clearly, Capp had drawn them.

I didn’t find corresponding panels for everything in the report. A few of the panels are probably from Sunday strips. The Kitchen Sink Press volumes do not include Sundays, so without a convenient way of discovering the “originals” of those panels, I could not compare the two. But I found the originally published versions of most of the dubious pictures, and based on those panels, Fisher had evidence enough to support his accusations without having to forge any.

In their Capp biography, Schumacher and Kitchen agree that Capp drew the offending pictures, albeit their assertion is considerably more circumspect than mine: “For discerning readers, including Fisher, Capp’s frequent visual and verbal double entendres were indisputable, but they were always clever enough to be ambiguous and thus fly below the radar of the vast majority of unassuming readers.” In support of this view, they reprint a couple of the tamer specimens.

The Ethics Committee almost certainly did not make the kind of comparison I did. By the time it met to consider the case, the strips at issue were not readily available for comparison purposes: It had been five to nine years since they had been published in newspapers, and there was no ready access to strips that had been published so long ago. Besides, making such a comparison would have been pointless: Most of the cartoonists doubtless recognized in the visual contrivances of the strips in question a kind of prankster spirit on the loose. They would scarcely be blind to what Capp was doing. Kahn wasn’t. And what Capp was doing — out there in the open — was hardly a secret. Not after Confidential. Not after the New Yorker profile.

A few years ago, I talked with Beetle Bailey’s Mort Walker, who was on the Ethics Committee at the time of this incident. He confirmed my view that the Capp drawings had not been doctored — not in the usual sense. Fisher did not do his tampering with a pencil or pen; he did it with a pair of scissors. What he did, and it is readily apparent in a comparison of the strip’s published panels to those supplied to the Joint Committee, was to crop the panels in ways that focused attention on the lascivious parts of the drawings. The way the Nov. 28, 1948 panel is cropped, for example, makes it appear that the woman is straddling the man in a posture of sexual intercourse.

In many instances, Fisher did no cropping at all: Isolating the panel was itself enough to draw attention to a nose that looked like a penis, or a keychain that seemed to outline a penis. Fisher was undoubtedly innocent of any actual drawing; but Capp wasn’t.

Writing in The Comics Journal #147 (December 1991), comics scholar Martin Williams described in some detail the imagery Capp had hidden in plain sight. Saying Capp was indulging “an obsession with what might be called visual double entendres,” Williams cited his evidence:

There were knotholes in his trees. By 1940 they were becoming more and more prevalent and more and more vaginal. Then there were abundant penis shapes. Once Available Jones [Dateless Brown] and his erect dicknose had made its appearance, Capp seemed to go all out. Jones’ cleft chin could be a scrotum from certain angles, and Capp became more and more fond of cleft chins. He even gave occasional dicknoses to some of the more aggressive female characters, particularly around Sadie Hawkins Day.

Then there were the occasional droopydong noses of some of his aged males. And I have said nothing about the rectal mouths of Jeeter Blugg and his daughter, which go all the way back to 1938. Or the many, many times the number 69 came up in Li’l Abner. In my generation, all of us teenage boys knew what was going on at the time, and so did some of our girlfriends.

No, I didn’t say “phallic symbols.” These were phalluses, penises — dicks. The simplest Indian peasant woman, psychologist Carl Jung once remarked, knows the difference between a penis and a phallic symbol (even if Freud did not).

But none of Capp’s playful porn was any longer at issue. By the time the Ethics Committee was deliberating in early 1955, the question of forgery was scarcely paramount. The important question was whether or not Fisher had circulated the strips, drawing attention to their salacious content. And his handwriting on the margins of the strips established to the Committee’s satisfaction that he had, indeed, distributed the incriminating material. In so doing, Fisher had delivered his colleagues into the hands of their enemies, the censorship forces then converging upon cartooning.

Fredric Wertham’s indictment of the comic-book industry, Seduction of the Innocent, had been published the previous winter. An early missionary effort at indicting mass entertainment media as the source of most social ills, this incendiary diatribe claimed that reading comic books seduced young people into imitating the criminal behavior often depicted in the four-color pulp narratives, thus making comic books responsible for juvenile delinquency. In April 1954, the U.S. Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency held hearings in New York to take testimony about the possible evil influence of comic books.

While the government eventually undertook no action against the comic-book industry, the publishers themselves did. In September 1954, they formed the Comics Magazine Association of America, a watchdog operation charged with seeing that its member publishers followed a code to which they all voluntarily subscribed. In addition to prohibiting such obvious affronts as using profanity in comic books, the Code forbade pictures of scantily clad women, excessive violence, anti-social behavior of all kinds, and even the use of the words “crime” and “horror” in comic-book titles.

In this climate, syndicated newspaper cartoonists could be forgiven a certain measure of paranoia about their future. All of them already endured two levels of “prepublication review” for editorial approval with everything they did — first from their syndicate editors and then from the client newspaper editors — and they were understandably anxious about what additional restrictions might be imposed upon their creative efforts. In defending Capp by saying that the sexual content in his drawings was the work of a forger, Caniff and Raymond were defending themselves and their colleagues from the threat of additional “prepublication review,” a much larger issue than Capp’s perpetrating risqué pranks. As representatives of their profession — and of the NCS — they would be expected to do no less, however much it may have strained their ethics.

Did they lie to protect their colleagues? At first blush, it would seem so. But careful inspection of their letters absolves them of that sin. Almost. The language of Caniff’s letter, which Raymond pretty obviously copied in his, is carefully contrived to be both condemnatory and accurate: He writes about distorting, contracting and “withdrawing from context,” which is exactly what Fisher did. And Raymond, using some of the same expressions, added a few of his own, saying the Capp drawings had been “cropped, faked, wrongfully emphasized and twisted” to make them appear pornographic. In saying some of the pictures had been “faked,” Raymond may be crossing the line (although I suppose something could be “faked” without being “forged,” somehow), but neither Caniff nor Raymond asserted unequivocally that Fisher had redrawn or doctored the actual drawings. Not in so many words. A quibble of sophistry, no doubt; they came close enough to cast the necessary aspersions on Fisher. And their implications, without being outright falsehoods, effectively tainted Fisher’s reputation in the history of the medium. Despicably, Fisher had tried to destroy Capp’s professional standing and his livelihood; but he didn’t forge Li’l Abner drawings to do it.

Fisher’s effort to smear Capp amounted to a betrayal of his profession, and it was more for that than for the alleged forgeries that he was condemned and cast out of the Society. Considering that feeling among the cartoonists ran relentlessly against Fisher as a personality, the Society had been remarkably restrained in merely suspending him — and in giving him an indefinite period in which to respond and reclaim his standing in the membership. Whether Fisher could eventually have done something to redeem himself is moot. At the end of the year, he was dead. By his own hand.

Weiss found the body.

Anyone with any psychological acumen might have seen it coming. In spite of his brave words, Fisher was devastated by the suspension. He had been publicly humiliated. He could no longer go about in society among the celebrities whose company was so vital to his sense of wellbeing. He disappeared from New York’s cafe society. He stayed to himself. He brooded.

Weiss recalled this period when we talked: “What happened was, he was coming over to the house to spend time with me — regularly — to tell me all his problems as well as his troubles because I think, most of the people didn’t want to listen to that anymore. We had a couple of kids, and I was doing the drawing, and he’d come over. And Blanche said to him one time, ‘Look, Ham, you’ve got to let Morris work.’ So that was it. Later, my neighbor across the street said he saw Ham’s Cadillac driving by. And later Ham said to me, ‘You know, I used to drive by your house and say, “My friend lives there.”’ So he had become a martyr now in the last part of his life.”

Weiss felt that the ouster from NCS was extreme. “There were highly regarded cartoonists then — like Bob Dunn, Ernie Bushmiller and so many of them — Otto Soglow — who wanted no part of Ham being expelled,” he told me. “They felt it was a feud between Ham and Capp and it should rest at that. And Capp was no knight in shining armor. But the Board of Governors made the decision; they decided to expel him. That I thought was pretty crummy. They should have consulted other people — Russell Patterson, Bushmiller, Dunn, and others who were very active in the Society — before taking such a drastic measure against a famous cartoonist. They could have said, ‘Look, if he broke the law and Capp wants to sue him, let him sue him. See if he wins.’ But Capp never sued him.”

Weiss related the sad final sequence of events to New York Daily News writer Jay Maeder, who rehearsed it in Hogan’s Alley #8 (Fall 2000). Fisher visited Weiss at his New Jersey home the Friday before Christmas in 1955, distraught as usual. He often phoned Weiss, begging him “to drop everything and immediately join him for dinner because he was terrified to be alone with himself,” Maeder wrote. Weiss was a patient listener most of the time, and Fisher needed someone to pour out his troubles to.

Soon enough over coffee and cake Fisher lapsed into the old familiar self-pity, wailing again that his new young wife is leaving him, that his studio assistant Moe Leff is openly sneering at him, plotting against him, making him crazy ... and ... and ... oh, God, Weiss has heard it all before so many times.

As he left Weiss’s home, Fisher pleaded: “Please come to work for me,” he said.

“No,” Weiss said. But he knew that wouldn’t be the end of it.

Fisher phoned three days later, on Monday after Christmas. Again, he begged Weiss to come and work for him. But Weiss’s drawing board was piled with satisfying bread-and-butter jobs, and he had no time for another of Fisher’s self-pitying tirades.

“Help me,” Fisher entreats Weiss.

“No,” Weiss says firmly.

Fisher is blubbering now.

“Look, I can get you an artist,” Weiss snaps. “But do something. Fire Moe, get a divorce, give up the strip, sell it. Ham, I don’t want to hear anything else from you until you do something concrete.”

After all these years, Morris Weiss is at last at the end of his rope.

“Do something!” he shouts into the phone.

“Help me,” Fisher begs.

“Help yourself,” Weiss says.

There is a moment of silence.

“I will,” Fisher whispers. “I will tomorrow. God love you,” he finishes, and the line goes dead.

The next day — on the afternoon of Dec. 27 — Weiss received a phone call from Fisher’s young wife, Marilyn (nee Franklin). Married to Fisher only a year, she was alarmed because she couldn’t raise her husband at the studio. She called Weiss several times that afternoon. Finally, Weiss sighed and set out for Manhattan. He went to Moe Leff’s studio. Fisher had been using the studio while Leff was out of town. Persuading a janitor to let him in, Weiss saw Fisher prone on the daybed, an empty bottle of pills nearby. Fisher was dead. In two notes Weiss found near the body, Fisher had written that he was despondent about his health (he had diabetes and his eyesight was beginning to fail) and that he intended to take an overdose of some pills he had been using. “God will forgive me,” he wrote, “for I have provided for my family.” (Chiefly, Marilyn and his daughter, Wendy, the product of his first marriage to Carolyn Graham.)

Weiss cursed softly and phoned the Daily Mirror, the New York newspaper that had carried Joe Palooka from the beginning. He felt Fisher would want his flagship client to get the news first. Then he phoned the police. Then he phoned his wife to say he’d be late getting back home. And finally, he phoned Marilyn.

As soon as Milton Caniff heard the news of Fisher’s suicide, he thought of Capp. “I called his house in Boston,” he told me. “His kids were still at home then, and his daughter answered the phone. Al was out. And she said, ‘Any message?’ So I said, ‘Ham Fisher is dead.’ And she said, ‘Who did it?’ Didn’t ask how he died — she said, ‘Who did it?’ He was that cordially disliked.”

Maeder describes a bizarre incident in the aftermath. Lee Falk, who wrote The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician, told Maeder that he ran into Capp at the bar in Sardi’s shortly after Fisher’s funeral.

The two comics men talked shop for a while, and eventually the conversation turned to the recent sorry demise of the man who had created Joe Palooka.

Capp laughed the harsh laugh of the victor. “Ennobled it,” he said. “He has ennobled our feud.”

Capp turned to address the entire room. “He ennobled it,” he brayed. “It is a noble thing he did.”

Falk stared into his glass. My God, he said to himself — the man thinks this is Tristan and Isolde.