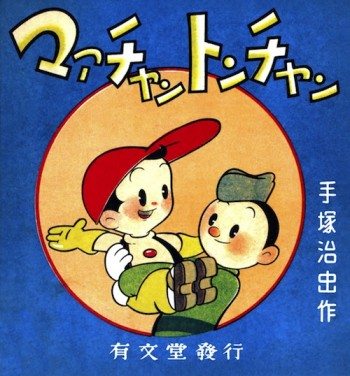

Last year, respected manga scholar Takeuchi Osamu asked me to contribute something about my research on Tezuka Osamu and American comics to Biranzi, a biannual, for-serious-archive-diggers-only coterie journal of manga scholarship that he edits and self-publishes. Unable at the time to whip up something new, I asked if he would be interested in a translation of “Gottfredson’s Heirs: Osamu Tezuka,” an overview of Tezuka’s debts to Floyd Gottfredson, with a focus on New Treasure Island (1946-47), that David Gerstein asked me to write for Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse Vol. 5: Outwits the Phantom Blot (Fantagraphics, 2014). The translation, which was kindly done by one of Takeuchi’s students at Dōshisha University in Kyoto, appeared in Biranzi, no. 34 (September 2014).

Now a year later, respected animation scholar Watanabe Yasushi (b. 1934), co-author of A History of Japanese Animated Films (Nihon animēshon eiga shi, 1978), a standard reference in the field for nearly forty years, has published a response to my article in the same journal (no. 36, September 2015), titled simply “Thoughts Regarding Gottfredson’s Heirs: Tezuka Osamu” (“Gottofuredoson no keishōsha Tezuka Osamu ni tsuite no kansō”).

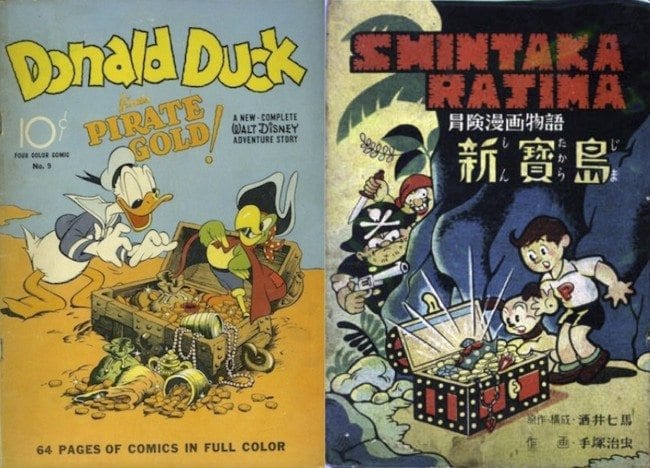

Nice to see my work being read in Japan. Sad that the first respondent had to come out with such a flippant and not very open-minded piece, as Watanabe writes me off as a nobody who apparently hasn’t read much scholarship on Tezuka or many of Tezuka’s early manga, and dismisses my claim for the central influence of Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse Outwits the Phantom Blot (Dell, 1941) and Carl Barks and Jack Hannah’s Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold (Dell, October 1942) on New Treasure Island with the repeated assertion that it was simply impossible, or at least extremely unlikely, that pre-1945 wartime American comic books would have found their way into post-surrender Japan. Watanabe's main argument boils down to the claim that, as an avid teenage collector of American comics via Osaka-area used bookstores and junk sellers during and after the Occupation, he personally never recalls seeing any pre-1945 samples. He makes no effort to engage with the visual evidence presented in the “Gottfredson’s Heirs,” and he does not appear to have bothered looking up the articles for The Comics Journal and PictureBox on which that article is based. I list them here for his (presumably Watanabe reads English) and anyone else’s convenience, including Japanese readers who might be inspired to google my name after reading Watanabe’s article.

“Tezuka Osamu and the Rectification of Mickey,” The Comics Journal (May 2012)

“Tezuka Osamu and American Comics,” The Comics Journal (July 2012)

“Manga Finds Pirate Gold,” The Comics Journal (October 2012)

“Tezuka Osamu Outwits the Phantom Blot,” The Comics Journal (February 2013)

“Osamu Tezuka and the First Story Manga,” in The Mysterious Underground Men (Picturebox, 2013)

For me, the visual evidence presented in the above TCJ articles (namely, "Manga Finds Pirate Gold" and "Tezuka Osamu Outwits the Phantom Blot") prove almost beyond a doubt that Tezuka and his collaborator Sakai Shichima had Phantom Blot and Pirate Gold on hand while creating New Treasure Island in the summer and fall of 1946. One might come to the conclusion that the resemblance is strong but not conclusive. But I think only someone who doesn’t bother to look at the images can dismiss my argument as nonsense, and fall back on a discredited understanding of August 1945 as an impermeable wall between past and future Japan.

I am in the process of writing for Biranzi a rebuttal to Watanabe’s piece, incorporating details from my TCJ articles for the benefit of Japanese readers who probably have never heard of me or The Comics Journal, or of Floyd Gottfredson. It’s quite pointless to air personal grievances before you, English readers, more than I already have above, since the debate is taking place in a Japanese publication for a Japanese audience. What I want to do here instead is briefly explore the question of pre-surrender wartime American comic books travelling to post-surrender Japan. Whether you are studying British, French, Japanese, of Filipino comics, the transformation of comics form due to the spread of American military forces around the world is a major art historical issue, and one I think demanding further documentation, cross-national mapping, and syncretic comparative study.

When I first presented my research on New Treasure Island at a lecture at Gakushuin University in Tokyo in July 2012, Ono Kōsei (who knows his American comics as deeply as his manga) voiced similar doubts, and I suspect that there are others who feel the same, at least in Japan. So visual evidence aside, it is an issue I need to address. Presently, I only have bits and pieces of circumstantial evidence and tangential hard evidence. I want to present them before you, as a way of asking if anyone has further thoughts or information on the matter, particularly from a non-Japan perspective. If you are not familiar with Tezuka’s relationship to American comics or with the visual evidence of Gottfredson, Barks, and Hannah’s influence on New Treasure Island, I urge you to first read the essays listed above. Assuming that you do have a basic grasp of the art history, I am going to limit discussion to questions that are necessary to respond to Watanabe’s claims.

Let me start by translating Watanabe’s main arguments. His article provides a long synopsis of Disney comics in Japan circa 1949-51, but as the main issue is a manga from 1946-47, the late Occupation period is ultimately irrelevant to the debate. Therefore, I’ll stick here to statements pertinent to New Treasure Island and the circulation of American comics in Japan immediately after the war. Some of Watanabe’s personal reminisces are useful for understanding the general situation in early postwar Japan, though I think they have blinded him to possibilities beyond his own 70-year-old memories.

How did one get their hands on American comics? After reading old magazines (which included Life, Look, Collier’s, and Time, in addition to comics), American soldiers threw them out, whereby they ended up with used book agents and ended up displayed in used bookstores. There were also waste agents who specialized in collecting things from the American military. Through those agents, [comics and magazines] were often sold by open-air street vendors (rōten) or they ended up on the black market (barrack-style shops were hastily constructed right after the war in the main bombed-out commercial districts, where food and other goods were sold at high prices through illegal routes). I bought comics from a used bookstore in the Namba area of Osaka that specialized in Western books and frequently got comics in. The comics on the black market or at rōten were rather expensive. I wasn’t too into action comics (gekiga-kei) like Superman or Batman, nor am I now. I mainly liked and collected Disney and other animal comics. Of course, available for purchase were only comics that postdated the American military’s arrival in Japan. There was not a single comic from before the war.

Then, after explaining the publishing history of Outwits the Phantom Blot, Watanabe continues, “I find it impossible to think that Tezuka got his hands on this prewar comic and was inspired by it for New Treasure Island.” Again later, after describing how Sakai reportedly produced the rough layouts and story outline and left the execution up to Tezuka, “After having looked at the Phantom Blot newspaper strip, I am utterly unconvinced that Tezuka used Gottfredson’s idea for New Treasure Island.” Which is followed by this: “Holmberg also writes that the second half of New Treasure Island and Sakai’s cover were inspired by Carl Barks and Jack Hannah’s Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, published in 1942. But there is no way that Tezuka could have obtained a comic book published during World War II. Even if it had been reprinted in America in 1947, contemporary conditions would have made it nearly impossible for Tezuka to have ordered it from America. Thus, I think there is no possibility that Tezuka could have seen this book.” (All quotes from Watanabe, pp. 34-35)

Let me note a few basic problems with Watanabe’s text, so that readers less familiar with this era’s history aren’t misled. Most of this I think can simply be chalked up to carelessness on Watanabe’s part.

1) He is unspecific about dates with regards to his own experiences of buying American comics. But judging from the rest of his article, he is probably recalling the late 40s or later, not the immediate post-surrender years in which New Treasure Island was created. Regardless, it’s not advisable to take one’s own experiences (recounted seven decades after the fact, moreover) as representing the totality of historical fact of experience in a given period.

2) The extent of Watanabe’s consideration of the visual evidence seems to be based on a reading of the newspaper strip version of The Phantom Blot in the Fantagraphics volume, not on the Dell comics. The layouts and panel sizes are fairly different.

3) He questions the possibility of Tezuka obtaining reprints directly from America, after himself saying that the typical methods for obtaining American comics for any Japanese during the Occupation was by buying them through used bookstores and junk vendors or, as Tezuka recalled in various texts, receiving them directly from American G.I.s. Also, as New Treasure Island was printed in January 1947, and created in the summer and autumn of 1946, Watanabe’s specter of a possible American reprint in 1947 is irrelevant.

Now let’s turn to the main issue: pre-August 1945 comics in Occupation Japan. Common sense simply tells me, Why not? Is that really so hard to imagine? But I think there’s much to be learned from actually grappling with the issue.

I think it useful to break the problem down into a set of linked questions. The goal in each case is to answer without resorting to internal visual evidence from New Treasure Island, which apparently wasn’t convincing enough for Mr. Watanabe, though I suspect he hardly bothered to look. I am also not going to proffer visual evidence from other Tezuka works or other era akahon, though I am sure if I spent a couple days with the Prange collection, they would pop right out. If anyone has further thoughts about how to beef these answers up, especially from an American or European angle, or if you have your own doubts about the evidence or my way of framing the questions, please do share. I am genuinely curious.

Question 1. Is there concrete evidence that Tezuka and/or Sakai were looking at American comics around the time they were making New Treasure Island?

Yes, and it comes directly from the horse’s mouth. What follows has been culled from my TCJ articles.

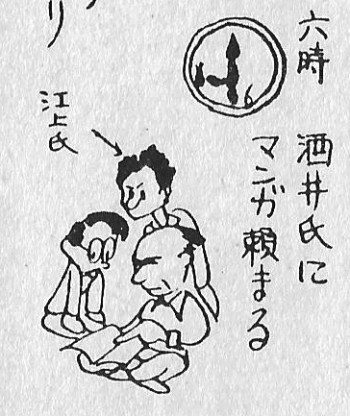

First, Tezuka’s diary. The artist admits to editing it (corrupting it) upon including pages as back matter to the 1984 edition of New Treasure Island, a total rewrite of the 1946 original. Yet he claims that it was only personal details of no relevance to manga history that were removed. Anyway, here is what he wrote (or says he wrote) on August 8, 1946, in the days leading up to New Treasure Island’s creation.

Around lunchtime, went to Sakai’s place in Tamade. We talked about various things, and then I gave him the artwork for Hello Manga. We beat up on American comic books until 3:30, and then I went to Nanba to watch A Ghost Walks the Streets of New York [Here Comes Mr. Jordan] for the second time. At night, [the Japanese version of Carey Grant’s] The Dancing Caterpillar [Once Upon a Time] aired on the radio for the first time in a long while. Ghosts walk, caterpillars dance, those Yankees sure are funny.

Then, appended to the August 20 entry, there is a caricature of Sakai holding something that looks suspiciously like a floppy American comic book, or perhaps the magazine Manga Man, which he edited. He is pointing at it intently, as if to say “Kore da” – “This is it, this is what I want” for a new type of postwar manga. In his study of Sakai, Nakano Haruyuki repeatedly states that Sakai owned American comics in these years (circa 1946-47) and pressed them on his peers and juniors as a model of what he thought postwar manga should become.

In an essay on Mozart from 1976, Tezuka recounts receiving a cache of comics from an American soldier named Joe in Osaka in the spring of 1946, before his work with Sakai began.

One day, completely in my own style, I was playing Mozart’s “Turkish March.” All of a sudden a Black soldier entered the room. There was nothing really strange about an American soldier being at the YMCA. He took a sheet of music from the piano, and once I was finished playing he began to sing in tenor. . . One day, after learning that I liked cartoons when I drew a quick caricature portrait of him, he brought me a mountain of American comic books. It was like the heavens opened and rained manna. There were absolutely no manga materials around at the time. I read through them like a worm, was overjoyed, and copied them obsessively. . . My friendship with him might have been short, but it became the reason I decided to become a manga artist.

Thus, we know that, even without looking at Tezuka’s manga from 1946, which do indeed reflect influences from Disney comic books, Tezuka had in his possession a number of American comic books and felt strongly about them. The same seems to go for Sakai, though his cartoons suggest a very different kind of influence.

Were we to follow Watanabe’s strict 1945-ist logic, these comics had to have been published after the war. That means that the comics Tezuka received from Opera Joe had to have been published between August 1945 and the spring of 1946, and the comics he and Sakai were looking at while planning New Treasure Island were printed between August 1945 and the date of Tezuka’s diary entry, August 1946. Though I have only researched a couple of titles (see, for example, my essay in The Mysterious Underground Men), most of Tezuka’s swipes from American comics do indeed seem to come from comics, particularly Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, dated from post-surrender 1945, 1946, and 1947. But is that reason to think that he wasn’t also looking at pre-surrender issues? Was 1945 really as impervious as Watanabe assumes?

Question 2. If Tezuka and Sakai were looking at American comics, is there any grounds for thinking that some of them were published during or just before the war? How likely was it for a comic published from 1941-42 to have survived the war and made its way to Japan in or after 1945?

Watanabe thinks it impossible. I think it perfectly possible.

First, it is well known that American soldiers loved cartoons. There is, for example, the famous report by Sgt. Sanderson Vanderbilt in Yank: The Army Weekly (November 23, 1945), a magazine for armed services’ personnel, in which he writes, “It’s no news to anyone who has ever killed a Sunday sprawled on his sack in a barracks that GIs go for comic magazines in a big way. At PXs in the States purchases of these books run 10 times higher than the combined sales of the Saturday Evening Post and Reader’s Digest. What’s more, we’ve got Market Research’s word for it that 44 percent of all Joes in training camps read the books regularly and another 13 percent take a gander at them now and then.”

Given the article’s date (November 1945), Vanderbilt would seem to be referring to GIs after the war, and particularly those stationed inside the United States. One cannot imagine, however, that this penchant for comics appeared out of the blue once the war ended, nor that the circulation of comic books was limited to stateside PXs and camps. Circumstantial evidence suggests that they were also consumed at bases in Europe and the Pacific during World War II. For example, artistic airmen painted Disney and Warner Bros. characters on the noses of fighters and bombers, identifying with characters like Mickey, Donald Duck, Zeke (the big bad wolf), and Foghorn Leghorn (the overbearing southerner rooster) enough to place them, as self-caricatures, next to renditions of sexy pin-up girls. They were drawing from cartoon imagery broadly, but some of the poses suggest copying from comic book panels, which would have meant issues published by Dell. The Disney Studio itself probably facilitated the distribution of its comics to servicemen, as suggested below. But one imagines (as suggested by not-so-reliable statements scattered online) that they also arrived via care packages, or perhaps through organizations like the Red Cross and the USO. Are there records of such activities? Personal anecdotes?

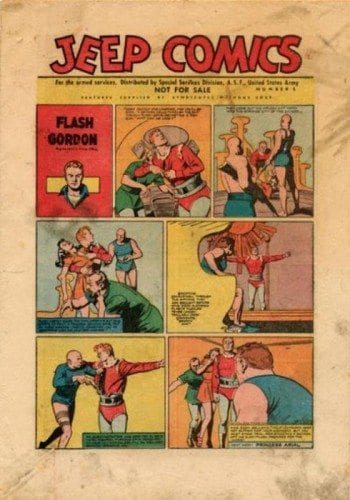

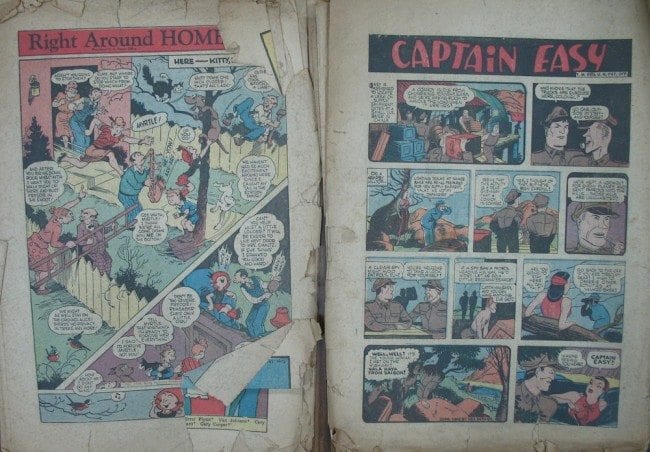

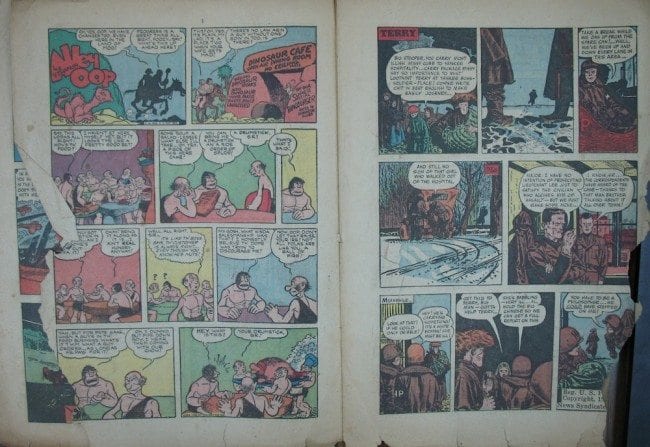

There were also reprints of comics designed specifically for servicemen. The Special Services Division, the entertainment division of the United States Army, created a number of such titles during and immediately after the war. They included Overseas Comics (1944-46), Jeep Comics (1945-46), and G.I. Comics (1945-46), fronted respectively by Bringing Up Father, Flash Gordon, and Blondie. Inside was a line-up of everyone’s (including Tezuka’s) favorites, including Superman, Gasoline Alley, Popeye, L’il Abner, Alley Oop, Dick Tracy, and Terry and the Pirates. As the bold “NOT FOR SALE” in the title block attests, these reprint editions were distributed for free to military personnel, presumably mainly those overseas who did not have access to American newsstand publications. The magazines also state, “features are supplied by syndicates without cost.” Judging from their publication dates (which I have taken from the Grand Comics Database), I suspect they were published with the downtime and homesickness of post-combat Occupation in mind.

Anyway, there were presumably lots and all kinds of comics circulating through barracks, camps, and sleeping quarters during the war. Does Watanabe think that these comics just evaporated when the Axis powers surrendered? I imagine there’s quite a bit of evidence to the contrary in Europe. As for Japan, there even exists photographic evidence that wartime comics (and not just military-only reprints) accompanied soldiers in the Occupation.

When you first visit the Prange Collection at the University of Maryland, they make you watch an introductory video about the collection. You can watch it online here. Informative generally, it also includes some nice film footage from the Occupation period.

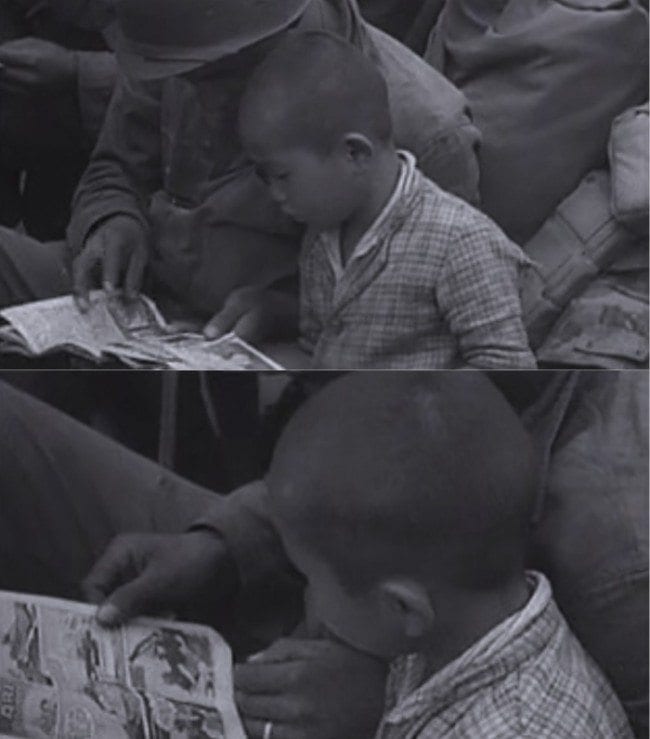

Behold! In one segment (starting at around 8:40), which is probably intended to communicate "democratization through reading," one boy is shown looking at some kind of flier, then another a boy is shown looking at a booklet teaching English phrases.

Finally, a younger Japanese boy is shown an American comic book by a helmeted American G.I.

Project Postwar Democracy: Comics reporting for duty, SIR!

I like that you can see the soldier's wedding ring.

Unfortunately, the Prange does not have records identifying the footage’s original source. They suspect it came from the National Archives, also in College Park. I managed to get in touch with the film’s director, Mac Nelson, but he only referred me back to the Prange. I guess that means a hunting trip to the National Archives next time I am in Maryland. With the one boy reading an English language lesson, the footage seems half posed at the very least. I don’t take it for a record of what Japanese kids spontaneously did after the war. Regardless, it’s the props and setting that count.

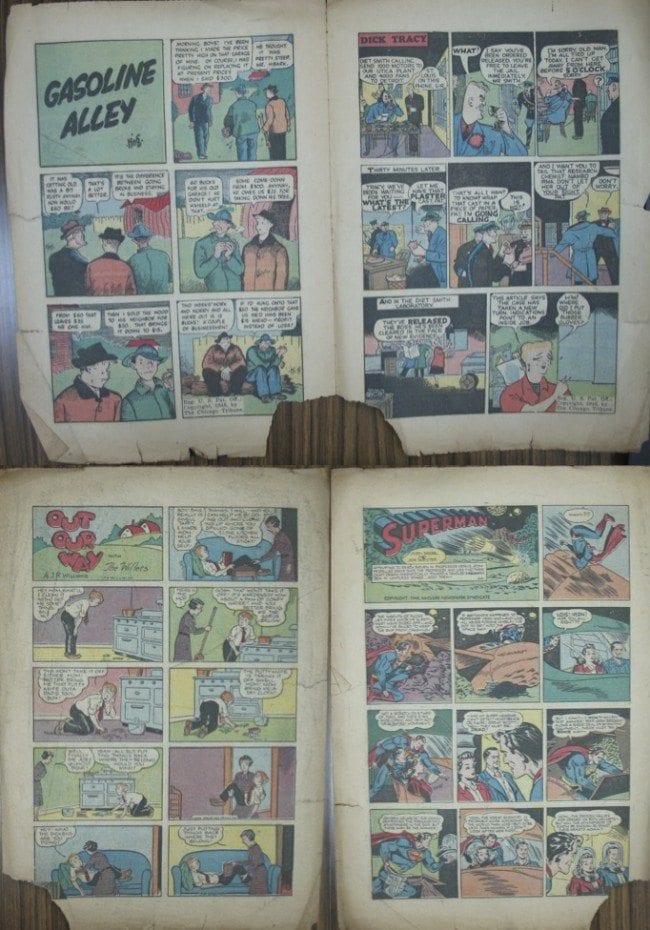

What is the comic book shown? It’s tough to make out in the soldier’s lap, but as he turns the page you get a decent view of large panels featuring air or sea craft, and the letters A-R-E in the top left panel. As usual, I sourced the ID out to my American comic book connections before bothering with the legwork myself. Within hours, Mike Rhode hooked me up with Ray Bottorff Jr., who helps run Grand Comics Database, and who quickly identified this as the title page of the Dickie Dare story in Famous Funnies no. 128 (March 1945). Coincidentally, since this is all occurring under the sign of New Treasure Island, this chapter of Dickie Dare occurs on boats at sea, with action scenes through big panels and minimal text, just the kind of thing Sakai and Tezuka liked and underwrote the famous “cinematic techniques” revolution in manga. But more importantly for the present inquiry, notice the publication date: March 1945, a few months before the Japanese surrendered.

Unless this is actually a postwar reprint of an earlier Famous Funnies issue (unlikely if even possible), what we have here is clear evidence of an American soldier physically sharing pre-surrender comics with the Japanese after the war. It doesn’t matter if the footage is posed. The fact is that a pre-surrender comic was present, even if only as a propaganda prop, in post-surrender Japan. How did it get there? Was it shipped directly from the States? Was it relocated from a base elsewhere in the Pacific? Was it lying around in the sleeping quarters of a ship, whereby it came ashore with the Occupation forces once hostilities ended? Was it intentionally brought ashore for photo-ops and ingratiating soldiers with local kids? Impossible to say, but the exact how of its immigration doesn’t really matter. There was at least ONE pre-surrender American comic book in Occupation period Japan. And where there was one, surely there were more.

This Famous Funnies issue doesn’t get us back to books from hoary old 1941-42. But at least we have crossed the cognitive barrier of August 1945, and put paid to Watanabe’s overly strict periodization.

Question 3. Even if other American comics were trotting the globe, is there any evidence that Phantom Blot or Pirate Gold specifically were issued in reprints, either during the war and immediately after, to increase their likelihood of ending up in Japan?

I don’t know, but someone reading this should.

What I do know is that Disney was hyperactive during the war. Fully supportive of the war effort, the studio made propaganda films for both the homefront and for foreign distribution. They created posters encouraging Americans to buy war bonds and donate blood, and (on an informal basis) helped the Lockheed factory in Los Angeles camouflage its buildings and decorate the side of its crafts with Disney characters. Free of charge, they also created insignia designs for more than a thousand military units amongst the Allies worldwide. There were a number of war-themed Disney comic books, like Pluto Saves the Ship (1942). In the margins, young readers are urged to “help keep America strong” and “buy war savings bonds and stamps,” which are described as “the best investment in the world.”

I imagine that Disney might have facilitated, in some form, the sending of comic books to servicemen overseas. As for editions specifically for the armed forces, the only example I know of is the inclusion of short Donald Duck humor strips in Overseas Comics, presumably recycled from Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. I don’t know if other Disney titles appeared in this or other armed service giveaways.

Anyone?

Question 4. By the way, is there any physical evidence that Tezuka himself owned American comic books dating from the war or just before? How about reprints of the same?

To the first question, not that I know of. To the second, yes.

I have the privilege of being, I believe, the only researcher to be shown what’s left of Tezuka Osamu’s collection of American comic books. This thanks to the generosity of Mori Haruji, head curator and archivist at Tezuka Pro. I have been meaning to create a full list of what is there, but another time. As you would expect, the collection is dominated by Disney comics, other funny animal comics, and Popeye comics from the years 1949-51, mainly published by Dell. The earliest, easily identifiable, newsstand comic book is Blondie Comics no. 10 (David McKay, February-March 1947), followed by Batman no. 40 (DC Comics, April 1947).

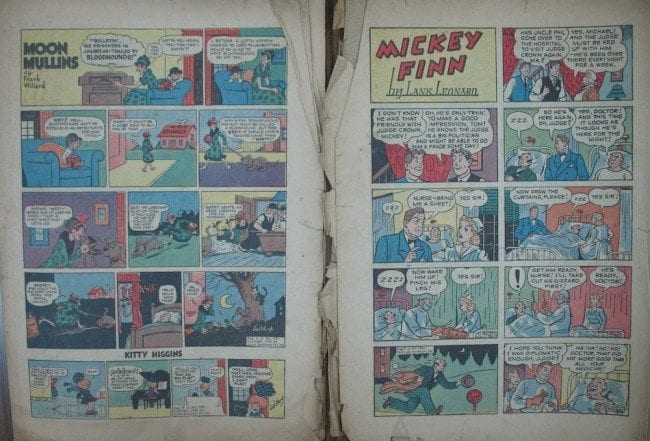

As for reprints, there is an issue of Overseas Comics from 1946, though because I photographed it with one of the corners folded over, I don't know the issue number.

There does not seem to be anything from before 1945. But there are a number of page scraps from what appear to be other ASF freebie reprint issues, as well as I think one Disney comic, marked with individual copyright dates of 1945 and 1946. Can anyone identify the publication and date? Maybe some are from before the Japanese surrender? When I photographed them, I did so carelessly, so I am not sure if some of these are pages from different magazines or separate ones. I’ll group them here the best I can.

Item 1, copyright dated 1946:

Item 2, copyright dated 1945:

More unidentifiable junk. See captions for copyright year.

Any help with the above IDs would be greatly appreciated. I would also love to hear of related stories, situations, and artist’s collections in places like England, France, Italy, or Germany. As I said at the beginning, I think there’s much useful research to be done to document and map how exactly the movement of American troops and bases during and after World War II reshaped comics across the world.