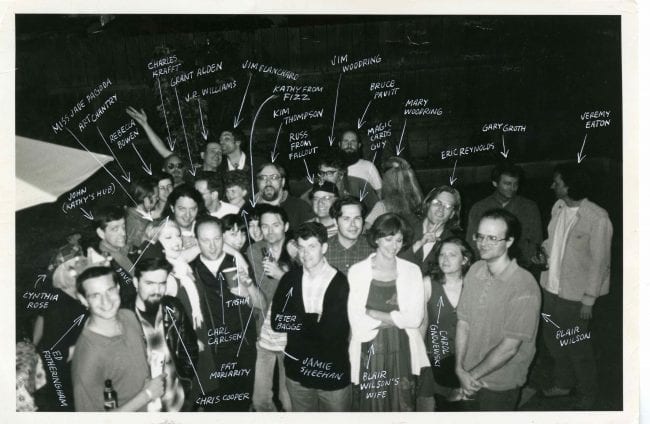

The following is an excerpt from We Told You So: Comics as Art, the long-awaited oral history of Fantagraphics Books put together by Tom Spurgeon with Michael Dean. A tumultuous magazine for a tumultuous industry; Barry Windsor-Smith troubles Jim Shooter's lower gut; the "I Am Not Terry Beatty's Girlfriend" Contest; Helena Harvilicz blows up; Frank Young melts down; and Eric Reynolds and Tom Spurgeon: the non-sociopath years.

The Comics Journal vs. The Comics Industry

Barry Windsor-Smith, cartoonist: In the early 1990s, Jim Shooter, Bob Layton and I were traveling to a downtown restaurant. We were crowded in the back of a yellow cab, and the chat was inevitably about the world of comic books. I wasn’t interested, so I was tuned out, thinking of things other than comics.

But then, the mention of The Comics Journal caught my attention and I briefly tuned back into the conversation as Bob snorted, “Fuckers!” with Jim concurring — “Those bastards.” It’s rare for Shooter to curse. I guess he reserves his expletives for The Comics Journal.

Chiming in, I said, “The Journal is the only real magazine we’ve got.” In that context, where Jim and Bob were openly hostile, my use of the term “magazine” implied an arbiter of taste, criticism and intelligence, like The New Yorker, for instance. They both looked at me briefly, and, turning away, Shooter’s ass tightened so fast that it almost overtook the speed of Layton’s gall bladder stricture — what little air was in the back of the taxi was immediately sucked into each of their lower guts with a thunderous stereophonic whistling sound. Following through, I said, “Damned good thing they keep us on our toes, right?”

The rest of the short journey down Broadway passed in silence. Staring out the window while returning to my private musings, I coined the ungainly term Reverse Fart.

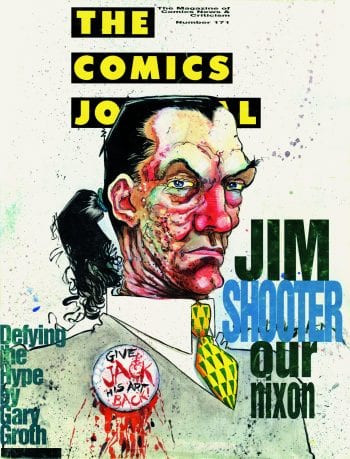

Gary Groth: The “industry” at large, of which 90 percent or more consisted of Marvel and DC (and Archie), had schizophrenic views of us. In the early days, we would give Gerber and Thomas and Englehart space to rant about Marvel and Jim Shooter, which they appreciated insofar as comics creators had never had a public forum available to them to voice their grievances; it was really the first time that a magazine would give them that kind of space and allow them to express themselves uncensored. Before that, fanzines toed the company line and the vast majority of creators were frankly too feckless to speak out. And to be fair, the Journal could be perceived as schizophrenic: We’d often run negative reviews of their books while championing their rights as artists. So there was always a tension there. Some comics creators respected our willingness to uphold artistic standards and give even creators we didn’t necessarily believe maintained those standards a place to speak out, and there were other comics creators who despised us for our “attitude.” Our attitude was a big problem.

Kim Thompson: That was the point, I think, at which the unity of alternative-minded mainstreamers and alternative cartoonists started to fray. It was a relationship that just couldn’t hold. They were based on improving the mainstream model, and we were based on bypassing it — or smashing it. There was also a residue of hostility because of all the mean things we said in reviews.

Groth: By the time WAP! showed up, I think the scales had been lifted from our eyes — or my eyes — and I realized corporations like DC and Marvel were not reformable and the only moral option was to not work for them — which was not something the Journal could effect. WAP! was interested in improving conditions so that artists could make more money producing crap rather than get fucked over for producing crap. I saw it as a venue confirming the work-for-hire status quo, which I was increasingly uncomfortable with. I came to the conclusion that producing crap was the problem, not how much one gets paid for it. Of course, self-publishing and indy publishing wasn’t the answer either, but I didn’t think it through that far. If I had, I would’ve realized there was no answer and slit my wrists.

Joe Sacco: I remember meeting Jim Shooter at one of the San Diego conventions and asking him for a quote about something or other, and him telling me, “I don’t talk to that rag.”

Powers: There are some things that I look back on during that period where I think they were a little too personal, and it doesn’t get any more nasty than the “I Am Not Terry Beatty’s Girlfriend” Contest. But I have no regrets. We started the Swipe File then. That I feel a little bad about in retrospect.

Thompson: I thought some of it was pointless bullshit and served no purpose other than to undercut the Journal’s reputation and create additional enemies for no good reason. But I had enough of the same inclinations and history that I had no moral high ground from which to speak, so all I could do is grouse about individual instances, to little effect. Thom and Gary tended to reinforce each other.

Groth: Thom edited the Journal briefly and even wrote news. We were very much in accord, editorially and philosophically, in that we wanted to use the magazine to confront entrenched attitudes in the profession and attack the whole ethos of hackery, and we were willing to use ridicule and humor to make our point. Nothing, I should add, was done frivolously. The whole point of the “Terry Beatty’s Girlfriend” Contest was to underscore how fatuous it was to defend drek. I still think that was pretty inspired, if I may say so. Although Kim’s own comics criticism could be devastating, he was always a little queasy about such tactics.

Thompson: There was always a lot of hostility towards The Comics Journal and Gary, and it tended to divide itself pretty cleanly. Those who liked and regarded as valid the model and aesthetic of mainstream comics didn’t like us, and those who didn’t like the model and aesthetic liked us. There were people on both sides who went the other way, but that’s kind of the way it broke down.

The “Contest” came out of a predictably negative review of some short-lived and now-forgotten DC comic called Wild Dog written by Max Allan Collins and drawn by Terry Beatty. The only two people who wrote in attacking the review and defending the comic were Terry Beatty and his girlfriend (in two separate letters). Before we got their letters, though, Beatty called me up and literally screamed at me for five minutes — livid. The letters were brimming with indignation. I thought this was so funny that I initiated a contest, open to Journal readers, to write in defending the comic; the winner would get a subscription to the Journal. The only criterion was that the contestant couldn’t be Terry Beatty’s girlfriend. We received a lot of entries, as I recall.

The Comics Journal’s Revolving Door

Dale Yarger: Comics Journal editors were a strange breed, as you probably know — they went through like three or four a year for a long time. At least it seemed like that.

Groth: If one of the skills I was looking for in a Journal editor was sanity, I should generally be considered a pretty dismal failure at hiring Journal editors.

Thompson: Some were pretty good but slightly neurotic editors who just eventually snapped, like Helena Harvilicz and Frank Young, whereas others explored the outer limits of office sociopathy.

Robert Boyd: It was a fucking stressful job. Gary was really unhelpful — certainly one of his weaknesses. He was totally hands-off unless he had a problem, then he could be kind of an asshole. I think if he had been a little more helpful and positive when people were doing a good job, they could have accepted his occasionally harsh criticisms a little better. But it was such a difficult job, and people would do it without ever getting a pat on the back. I mean, editors just killed themselves to get this magazine out.

Helena Harvilicz: I used to read The Comics Journal, and I found an ad for the managing editor job in The Comics Journal, and I just sent them a résumé — it was actually a really goofy cover letter that I wrote. I think I tried to impress them with how funny I was, or something. I got quotes from people who knew me, about how great I was. I think it must have impressed them, whatever it was. I’d been out of school a couple years and I had worked in restaurants, and at that point I was working at Georgetown University as a secretary.

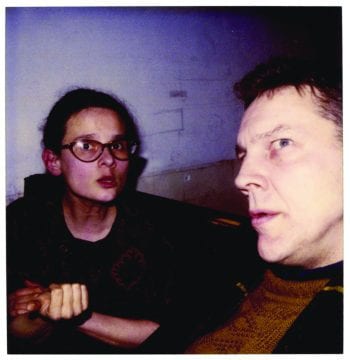

Thompson: Helena is a totally hilarious writer, a skill she was never able to really use in the Journal. She later did her own little fanzine, Nut Magnet, which was a masterpiece. She was also a character and a bit of a flake — this tiny, tiny woman who looked like she had barely hit puberty. My wife Lynn told me that she spent one of the first Fantagraphics parties she attended, when she didn’t know too many people, horrified that there was this 13-year-old girl drinking and smoking. “Is she someone’s daughter? Who brought her? Why isn’t anyone stopping this?”

And then they hired this guy, Greg Baisden. He went up to Seattle with them, and then I guess as it often happens with Comics Journal editors, he lasted a very short amount of time. I thought Greg was kind of an idiot when I met him.

Groth: Greg Baisden moved up with us from L.A. Greg was an extremely good editor as well as a good news writer, but he also had a mercurial temperament — almost the stereotype of a “good” Journal editor. You had to take the good with the bad and I was willing to do that. Greg’s work habits were extremely erratic, but he was extremely committed to The Mission and that meant a lot. But he was unstable and had a temper, which proved problematic.

Thompson: Greg wasn’t a bad editor, but he had what one might call anger-management problems. I once saw him throw an entire completed issue of Comics Journal paste-up boards across the room at Dale Yarger, but they fell apart like a poorly-packed snowball and Greg had to pick them all up again.

Groth: Once he even threw something at Dale Yarger’s head. I’m not sure if that or something subsequent was the last straw, but he left the magazine. Helena Harvilicz, who was working in tandem with him, took his place.

Thompson: He went on to work for Eclipse and then Tundra, and we would hear amusing reports from his tenures there.

Boyd: What would happen is that an editor would melt down mid-issue. This happened three times while I was there, first with Greg Baisden. I can’t remember what triggered it, but it had been building for a long time. That was the Kirby issue, and I basically finished it and started the next issue until Helena came on board.

Groth: I had been the primary editor of the Journal for the first eight or nine years (with, first, Mike Catron, then Kim Thompson), but at that point I had to devote more and more of my time to the company’s other publishing efforts and had to hire a managing editor to run the Journal on a day-to-day basis. Basically, the editorial template was there and I was still involved to greater or lesser degrees, depending upon how much time the rest of the company sucked out of me or what was going on in my personal life; sometimes I was very hands-on and sometimes not.

Hiring a new managing editor was always difficult. It requires a set of skills that are, if not unique, pretty rare, and I would often have to compromise because few applicants had them all. If I had to choose between someone with zero social skills and a broad knowledge of the history of comics and someone with excellent social skills and a spotty knowledge of the history of comics, I’d choose the former and reap the consequences in consequent office disruption. The people I eventually hired were usually intense, independent, focused and driven. And eccentric.

Harvilicz: They had remembered me for whatever reason and called me up again.

And at the time, I came across the country with this other guy, Thom Powers, and while we were driving he mentioned that I was going to be editor of The Comics Journal, which I was completely shocked about! I thought I was just going to be a reporter. I was working there for like two or three days, and Gary’s giving me all this stuff to do.

Frank Young: To succeed as managing editor of The Comics Journal, you need the skills of a samurai warrior and the fearlessness of an animal trainer. I doubt there are many people on this planet with both those skill sets and editorial and decision-making abilities. The job asks a lot of anyone.

Harvilicz: I went into his office and it wasn’t a breakdown, but I just looked at him and said, “Gary, I have no idea what I’m doing.” Because I had no experience. And he just looked at me and said, “I don’t want to hear it.” That was his training. At that point in my life it was perfect for me. Nowhere else was I going to get a job where I was going to be given so much control over anything.

Groth: I was still deeply involved in the Journal on a day-to-day basis then, conceptualizing the editorial lineup for each issue, conducting a lot of interviews, determining which books should be reviewed, going over the current possible news stories and determining which ones were important enough to pursue and so forth. Once those decisions were made, the managing editor had to make them happen. It was a dream job if you were so inclined, not so much if you weren’t.

Thompson: We always had a real sink-or-swim approach to employees, particularly the Comics Journal editors. I think in part because that’s how Gary and I had done it, although of course in our case we hadn’t been responsible to anyone else who might come down and yell at us. It was rough on some of them, but the ones who worked out always seemed grateful for the experience, and the ones who didn’t usually seemed to collapse because of character flaws or neuroses that had little to do with the actual skills.

Groth: I was stretched pretty thin by 1992 or 1993 — 15 years after I’d cofounded the magazine, and what I needed was a competent managing editor who could manage. I was still doing a lot of interviews at that time and I was writing for the magazine pretty often into the mid-’90s, but I couldn’t handle the day-to-day flow of … managing. So, the managing editor and the news writer and I would meet formally a couple times a week to discuss the forthcoming issue, and I’d answer questions, give marching orders and let them have at it. I would always give them a lot of latitude, but I have to admit that I felt the need to stand behind whatever feature or review or interview subject they suggested or I just couldn’t approve it. So, I was a little dictatorial that way, I guess, but I didn’t want the editorial core of the magazine to change.

Young: My story with Fantagraphics starts in 1990. I was living in Tallahassee, Florida, I was 27 and I was taking care of my mother, who had cancer. It was a pretty grim year for me, and I was feeling kind of trapped. Just for the hell of it, I sent a review of one of the Carl Barks Library sets to The Comics Journal. I had been reading The Comics Journal since I was in high school and I never had any idea that I would be affiliated with the company. By that time, I had 10 years experience as a published writer and editor, for a variety of newspapers and magazines, all in the Southeast.

Thompson: I remember when we interviewed Frank Young he went into great detail about how all his previous jobs were horrible and all his previous bosses were assholes. The ultimate fate of his Fantagraphics employment was laid out right there for us to see and we didn’t put two and two together.

Harvilicz: Gary never did anything with the magazine, except hire that idiot to write those horrible columns! Who is that guy — Ken Smith? You know, I went to Johns Hopkins, and I had a philosophy degree and I couldn’t read that shit. I tried to cut it every issue! Gary was evasive about it, completely. He would never ever answer the question of why is this in here?

I always wanted to make the magazine more lighthearted and funny. And the interviews were great, but they were way too long.

Groth: I’m not sure there was a single Comics Journal editor who didn’t hate Ken Smith’s philosophy column, which made me all the more adamant to run it, of course.

Young: I wrote this article basically to take my mind off this miserable situation I was in. I got a letter back from Helena saying that she liked the article, and it got published. I did four or five things for them over the next few months.

Groth: Frank Young — very smart guy who knew comics, had taste and appreciated the form, perfect Journal material. But there was the temperament issue again.

Young: A thing I noticed right away was what a combative and mutually abusive relationship Helena and Gary had. They were meant for each other, because they both could push each other’s buttons. I think to each other they were just giant consoles of buttons that would get reactions. They would have screaming matches. About anything. Helena would just fly off the handle. She was a very competent person, she knew what she was doing, but she had a very chaotic personality at the same time. She would get into arguments with Gary about very trivial things that didn’t really have any importance. And he would just keep pushing her buttons until she would explode. And she would just freak out, and I think it was just great entertainment to him. He didn’t have any emotional investment in it.

Groth: I liked Helena. We had a volatile relationship, but I never took our arguments personally, and I didn’t think she did, though I could be wrong about that.

Harvilicz: I had no friends, I knew no one and I lived in the attic at the office at one point. It was really a crawlspace that I lived in for a couple months.

Groth: At one point, Helena asked me if she could crash in the attic for a while. I said, “Are you sure?” I mean, it was an attic on the same level as the Journal office on the second floor of the house, but the roof slanted down and you literally couldn’t stand up in it. Well, Helena could probably stand up on the far side against the wall, but then she’d have to crouch down if she moved a foot into it. I shrugged and said OK. She lived there for a couple months — rent free, of course; it was, I thought, a temporary measure. She’d make jokes about how any guy who came into her “home” had no other option than to get on his knees immediately.

Boyd: Then Helena quit suddenly.

Harvilicz: As much as I loved working there, mentally I was all over the place back then, and I felt like I’d learned the job. It wasn’t like I was the best magazine editor ever, but I understood it, and I was like: OK, what else is there? I really wanted to move into doing something else for Fantagraphics. Like being an editor — I was sort of lining up do that, and he’d given me a book to work on. And then we had that blowup.

Thompson: Gary and Helena were a volatile combination. Helena was a pretty good editor but she’d have these blind spots and sometimes not think things through, and Gary would get legitimately annoyed with her and call her on the carpet, and he’s not particularly gentle as a reprimander and she was fairly sensitive and argumentative. I could hear them screaming at each other in Gary’s office since we shared a wall.

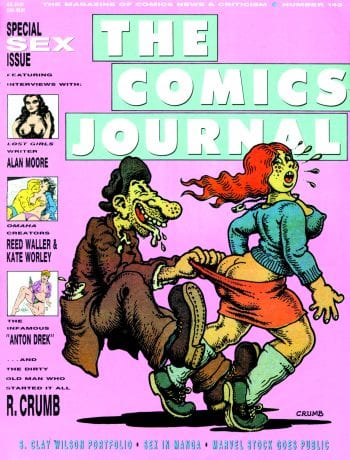

I remember we were at a San Diego convention, Lynn Johnston was attending, and Gary told Helena to go introduce herself, give Johnston a copy of the magazine and ask if we could do an interview. Of all the issues to give this nice middle-aged Canadian newspaper cartoonist, Helena gave her the recently released “sex issue” of the Journal, which was totally filthy, full of hardcore porn images. Miraculously, Johnston weathered the blow and did eventually agree to the interview, but it led to one of those “Why did you do that?” colloquies in Gary’s office.

I really wanted Gary to be kind of like a mentor to me, which was just never ever going to happen. I was a little disappointed. I think Kim was a little more nurturing than Gary — I really liked Kim.

Thompson: Helena and I got along great, but then, I didn’t have to deal with her professionally. I don’t know if I’d have handled the Helena problems better than Gary. I had a mild crush on her, actually, which I confessed to her years later in San Diego when we were both drunk off our asses, and she said she’d had one on me too, but in her case it may have been the liquor talking, or she was just being nice. I don’t know. Of all the oddballs who trooped through the Fantagraphics offices, she’s one of my favorites.

Groth: I really liked Helena, but she was such a goofball that I may not have taken her as seriously as I should have. She would do a very competent job and then make a decision or say something so absurd or foolish or ignorant that I would go crazy and that would stick in my mind more than all the rest of her professional engagement.

Harvilicz: You know, I was feeling like I could take so much shit from Gary, and I really just did not let it bother me at all — a lot of it was shit I deserved. I remember one time he called me in his office after I’d done this interview, and he said, “Sit down — I want you to hear something.” So then he starts playing the tape back of me interviewing this guy — and this goes on for like five minutes. And he goes — “Now, did you notice that every time this guy started to say something interesting, you had to open your mouth?”

Young: Helena quit on Labor Day of 1991. We had just finished issue #144 and something happened over the weekend and she just exploded for the last time. She left a resignation letter that just said, “I have quit. Sincerely, Helena Harvilicz.”

Harvilicz: I remember going into that office and leaving a note — “I’m quitting, I’m going out to get drunk, this is my two-week notice.” And just put it on Gary’s desk. Because of the nature of who he is, or our relationship or whatever, he didn’t really even bother to follow up on it. He was like, “Fine, you quit.” OK. I think maybe if he would have apologized, I probably would have stayed.

You know, he’s one of those people who has to win, no matter what it is. He doesn’t really want to talk about it. He’s right, and whatever. On the one hand, though, it was like that’s great — I never had a boss before that I could go up to and say “fuck you” — you know? At least he takes it. He won’t admit he’s wrong, but he’ll at least listen to you give him shit.

In some ways I kind of regretted [quitting Fantagraphics], because I felt like at that time, I loved comics so much, and I just loved the company and everything.

Harvilicz: I got drunk one night after I quit or was fired, I don’t remember what happened. And I called him up and said, “Uh, Gary — I want to come back and edit the Journal.” And he was like, really? I think he was like considering it. And I was like, yeah. And then the next day I sobered up and thought, “I don’t know why I did that, I’m never going back there!”

Young: I was helping someone move that day and afterwards I came into the office and there was a typed note from Kim Thompson on my desk that said, “Congratulations, you’re now the managing editor of The Comics Journal.” Without even asking me. It was quite the promotion.

I definitely had an agenda of making the magazine less threatening to the comics world. I was really excited to come out here and meet all these cartoonists, and as soon as anyone found out I was associated with The Comics Journal they would clam up. It was a little crushing, because, at the time, I had been making comics and was entertaining the thought of taking it seriously, and here I found myself at the epicenter of it and the only person that was really accepting was Pat Moriarity. Of all the people in the Fantagraphics world at the time, he was the most unguardedly friendly. He was interested in seeing the work I’d done and was very encouraging.

But the work schedule I had at the Journal left me with no energy to do anything else anyway. It was an extremely labor intensive magazine because everything was done by hand — all the graphics, color separations and typesetting. They processed photographic material with these foul-smelling chemicals, which gave me some chronic health problems for several years after. I was hoarse for two years afterwards and never have gotten my speaking volume back completely. There were people there like Dale Yarger, putting in these 20-hour days, who used to sleep at the office. That was the one thing that I wouldn’t do, even if I was working till 4 in the morning, I would go home to the insane Greenhouse in Ballard, where I lived with Tom [Harrington], Pat and Helena — the Fantastic Four. Helena began to see me as an old grouch, because I would complain about her ranting and raving at all hours — whooping it up and banging pots and pans and screaming like a gibbon.

Despite all the crazy stuff, I was actually very excited about working on The Comics Journal, but it had gotten a bad reputation as just a soapbox for Gary’s whims, to the point where if I had to do a news story and had to call someone, I’d get hung up on. I wanted to improve that somehow and I know that Gary didn’t like that — he made some passive-aggressive comments.

I have to say, I do like Kim, and of the two of them, I would say he’s the more levelheaded, business-like. He has some real problems with being passive-aggressive, and if Gary would get him going, he would just go along with things. I think Gary’s self-image was like Hawkeye from M.A.S.H. This zany guy that was sticking it to the establishment. The witty, charismatic guy that was putting the screws to the man, and Kim would get caught in the undertow of that sometimes. But on his own, Kim could also be, if overly harsh and critical, also very helpful.

I wasn’t very happy and I wasn’t getting paid very well, but I did like what I was doing on the magazine. It was getting at the idea I had, which was a magazine that was still part of Gary’s psyche, but was not something that people would hang up the phone on.

The straw that broke this camel’s back was the aftermath of the infamous Todd McFarlane issue, the mainstream issue. Dale and I had just busted our butts to get this issue out for San Diego. It was a tall order, but we dug in and delivered the goods on time. After the issue came out, and everyone else was having fun in San Diego, I took four days off — I was putting in 70, 80 hours a week, and just not getting anything back in return.

Gary and Kim called me into Gary’s office and proceeded to play this game of good cop/bad cop with me. Despite the fact that I had done what I thought was superior work for them for lousy pay, it was just the ultimate “fuck you” from both of them. I was just sitting there feeling so shocked and mortified I couldn’t say anything. Basically, they were telling me that I was doing a rotten job, and the Journal really sucked, all of which I knew wasn’t true. And the bottom line was that they wanted to finish up this special Harvey Kurtzman issue I was working on — a pet project of mine I’d been assembling for a year — they wanted to just slap it together as quickly as possible. Most of it was completed, or in the editing stages, but I wanted to finesse it. I just remember feeling so crushed, because they were basically telling me, well you poor pathetic schmuck, you’re just completely worthless and untalented, but no one else is dumb enough to take this job so we’re going to let you keep it. But you’ve got to work even harder and put less care and quality control into your work. And I did something I’ve never done before and never done since — I didn’t even clean out my desk. I just walked out of the place and never came back.

Thompson: The Frank Young thing was weird. The Comics Journal was always battling scheduling problems, but Frank had gotten fixated on the Kurtzman issue and it looked like it was going to take forever, just fuck up the schedule beyond its normal state of fucked-upness, mess up cash flow, advertisers, subscribers … It was like Michael Cimino edits a Comics Journal. We had some sympathy for him wanting to really bust his ass on it, but we weren’t in a position to let it slide for as long as it looked like it was, and we had a meeting where we told him he had to get it out. So far as I remember it was perfectly amicable, which just goes to show you: His perception was that we raked him over the coals for two hours. He sat there and looked at the floor and said “OK,” and the next morning there was a five-page single-spaced letter from Frank, which amounted to, “How dare you ruin my magazine, fuck you, I quit,” and that was the last we saw of him. He’d clearly been saving up his grievances.

Frank ended up working, at least for a while, as an usher at one of Seattle’s main movie theaters, so that was a little awkward, but we’re OK now.

Young: I was really upset and I wrote a scathing letter to Kim and Gary. If I had to do it all over again, I would have said these things in person. It was just a year’s worth of bottled-up frustration and rage. I found out later that some of the stuff I said about Kim and the way he treated people had some positive impact — I found out that he was being a lot nicer to people. I regret the harshness of the tone of that letter, but it was the best I could do at the time.

Groth: It’s always the delicate flowers who insist on their sensitivity in the face of the relentless negativity of the Journal office who write the bitter, five-page letters of resignation dripping with venom and bile. Frank Young’s ex post facto letter of resignation was a masterpiece of the genre.

Harvilicz: Then this Carole Sobocinski was hired, and that was like some nightmare that happened with her.

Yarger: Even when we were putting the Journal out weeks and months late, generally editors were a pretty devoted bunch, so I was used to a high level of commitment. They weren’t all as organized as they might have been, but they were committed. And Carole didn’t seem to have that same approach to the Journal, so it made my job a lot harder.

Boyd: I left right before Carole Sobocinski melted down. At first, we really got along, but after a while, I felt kind of used by her. We were barely speaking when I left. I wrote her a memo saying I wanted to keep writing Minimalism. She wrote back a terse note saying, “No, I’m taking it over. Give me all the minis you have to review.” I guess I could have gone to Gary or Kim and asked them, but I thought, “Fuck it.”

I had a huge box of unread minis that I put on her desk. She came down and said, “What do you expect me to do with all these?”

I said, “These are all the minicomics that people sent me. I think some are good enough to be reviewed, but it’s up to you now.” She told me to pull out the ones I thought were good. I laughed and said, “You have got to be kidding. I quit. I don’t work here anymore. You wanted this job, you’ve got it.” Then she gave Minimalism back to me — with a note saying I could continue writing it.

Later, when the whole Sobocinski thing exploded, Kim called me up and said, congratulations. You were the first person here that Carole hated.

Thompson: I’d grown to loathe Carole for several months before the blowup — I thought she was deceitful, lazy and self-serving — and had been urging Gary to fire her, but he stuck with her for some reason. He and I were having some of our periodic issues at the time and I have this suspicion she was playing those. She was very shrewd. What a horrible woman.

Eric Reynolds: I literally started at TCJ the day that Carole Sobocinski cleared out her desk, if memory serves. I may have even taken over her desk. Although we never worked together, her presence loomed that entire summer, as all of her subterfuge slowly came out and into focus.

K. Thor Jensen, cartoonist: I applied for the managing editor position at The Comics Journal in, I think, 1994. Might have been 1995. Of course, since my résumé was a paper route, opening mail on the night shift at the phone company and digging ditches for Labor Ready, I didn’t even get a call back. Prodded by my housemates, I called Fantagraphics and asked to talk to Gary.

When he wasn’t there, the receptionist — I forget who it was — asked if I wanted to leave a message, which I did. As best as I can remember it, it was, “This is K. Thor Jensen and you’re going to regret not hiring me as managing editor of the Journal because I can out-fight, out-fuck, out-type and out-proofread any of the fat-ass Colin Upton wannabes on your staff.”

A few months after that, when I had a strip published in the Journal, I used that as my biographical note.

Young: I don’t know everyone who’s edited the magazine since but I know a lot of people have gone through the same cycle of being the wonder boy or girl at first, and then at the end of their run they’re just the lowest form of scum on the earth and everything bad for the next six months is blamed on them.

Reynolds: The names of TCJ editors who left their position on good terms is a pretty small list.

Groth: I have to admit that I probably didn’t have much patience then — or now, for that matter — for Journal editors retroactively whining over how much work it was to edit the magazine. Was it a lot of hard work? Damned right it was. Is there anything worth doing that isn’t hard work? I don’t remember anyone I interviewed for a managing editor position telling me that the reason he (or she) was applying was because he wanted to put in a minimal effort and have an easy, cushy job. I would be very up-front about it: I told anyone who applied that it was a lot of work, a lot of hours and required a lot of dedication to the mission of the magazine. To me, devoting full time to editing the magazine would be a dream job. You’re given enormous (but not complete) autonomy, you have an opportunity to shape every issue, it’s intellectually stimulating, journalistically courageous and enormously rewarding. Financially, it was admittedly lousy, but it’s not like the magazine was ever a moneymaker and it was an opportunity you’re not going to find much in the real world to exercise your critical and intellectual faculties with few compromises or corporate considerations. Anyone who found this too much of a hardship wasn’t cut out for the job.

(continued on next page)