Despite a host of memorably shocking elements ranging from visions of mass murder to abductions to conspiracy theories run amok, Nick Drnaso's two graphic novels so far are most notable for their empathy. His 2016 debut novel, Beverly, pulls you increasingly deeper into a loosely connected cast of repressed and aimless Midwesterners, repeatedly revealing unsettling new levels of humanizing detail as seemingly abstract supporting players become fully realized characters. But where Beverly was a short-story collection, Drnaso's new book, Sabrina, builds upon Beverly's quiet heartbreak and human insights for a longer-form, politically resonant tragedy.

Despite a host of memorably shocking elements ranging from visions of mass murder to abductions to conspiracy theories run amok, Nick Drnaso's two graphic novels so far are most notable for their empathy. His 2016 debut novel, Beverly, pulls you increasingly deeper into a loosely connected cast of repressed and aimless Midwesterners, repeatedly revealing unsettling new levels of humanizing detail as seemingly abstract supporting players become fully realized characters. But where Beverly was a short-story collection, Drnaso's new book, Sabrina, builds upon Beverly's quiet heartbreak and human insights for a longer-form, politically resonant tragedy.

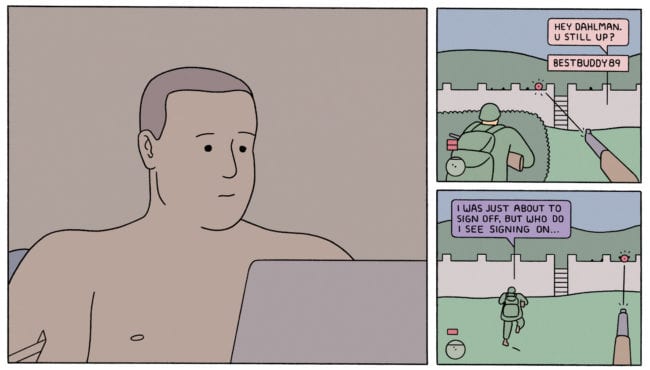

Sabrina follows multiple characters through their emotional fallout after the title character's shocking (and unshown) murder. Her boyfriend, Teddy, becomes deeply withdrawn and cynical, finding solace in an Alex Jones-style conspiracy-theorist radio program. Meanwhile, Teddy's friend Calvin, who takes Teddy in after the murder, is trying to maintain focus at his mundane military desk job while fighting off online trolls who accuse him of participating in a cover-up of the killing. Drnaso's tightly regimented panel grids and minimal cartooning style strongly recall Chris Ware, devastatingly emphasizing his characters' monotonous lives and oppressive need to put on a brave face in a punishing world.

If that all sounds a bit depressing, it is – but Drnaso isn't purely morbid, and he invests both Beverly and Sabrina with some surprising moments of subdued, yet affecting, redemption. We talked with him about how he briefly canceled Sabrina's publication out of concern that it was too "awful," the very real people his characters are based on, and his growing tendency towards a softer touch.

PATRICK DUNN: How did the idea for Sabrina start germinating?

PATRICK DUNN: How did the idea for Sabrina start germinating?

NICK DRNASO: It must have been late 2014. I was in a relationship. We’re about to get married, but at the time we were living separately. I started to have kind of overbearing thoughts of abduction and menace and danger all around. It was getting kind of unreasonable. It occurred to me I could tie it together with an idea of a person who goes to stay with a friend, which was based on my friend who was in the Air Force in Colorado Springs. So I kind of turned it into a good excuse to go see him. I took a train to Colorado to visit him and then take reference photos and just start to think about what the story could possibly be. Everything else past that was just total invention, fiction.

There’s some of that abduction and menace in Beverly as well. Where do you think that preoccupation came from for you?

I’m figuring that out. It was kind of a weird realization I had in the process of making Sabrina, that this was a deeply seated thing and something that I wasn’t even necessarily aware of. It was kind of disturbing when I realized there is some reason I am focusing on these things. It's fodder for creativity, I guess, but it’s not healthy at times. I had to sort of reckon with that towards the end of this project when it was really kind of taking its toll. It’s good to have some awareness about things like that, but going forward I have to be a little bit more careful about what I decide to focus on.

So do you feel you've moved past it more now?

Well, I hope so. Having an internal dilemma, like I said, it must be fueling creativity in some way. So it’s not like I would just hang on to it for the sake of torturing myself, you know, as material for stories. That’s kind of untenable. But even the other day I took a walk to the bank and on the way home I had this little bit of a story idea and I thought, "This is gonna be different. This is gonna be this very loving, kind of tender moment." And over the past few days I have been writing and drawing it and yet still there’s this infusion of – I guess just a pessimism or an uncertainty, like things can’t just be purely positive. So I am always kind of fighting against that. It would be all too easy to just focus way too much on negative emotions or negative behavior, fear, all those kinds of things.

You mentioned visiting your friend in Colorado Springs, which really made sense to me because Calvin’s life at work in the book just feels so real. Tell me about your experience learning about your friend’s life in Colorado Springs and the research you did there.

You mentioned visiting your friend in Colorado Springs, which really made sense to me because Calvin’s life at work in the book just feels so real. Tell me about your experience learning about your friend’s life in Colorado Springs and the research you did there.

He's my friend from childhood, so I kept up with him through his training and the reassignment, kind of moving around the country and kind of seeing more of the technical side of it. He’s on the side that is completely non-military information, kind of cybersecurity. I started to go out and talk to him and visit him, and then he drove me around Peterson Air Force Base where he worked and it just seemed like a big weird college campus. I didn’t realize a civilian like me could just go in and drive around and take pictures. They had a McDonald's on the site, which seemed like a funny detail that I didn’t want to put in [the book] because it just seemed like too much of a comment on our culture or something, a little obvious. But there were little funny details, like he said, “Oh yeah, we got this old-timey popcorn machine in the break room.” And I thought: okay, I have to put that in because it’s such an odd detail.

Has he gotten to read the book?

Yeah, I think he has as a matter of fact. Now he is out. He lives back in Chicago. I kind of warned him because there are elements of his life that I put into the book. I wanted to make sure he knows that it’s fiction, that it’s not any sort of comment on him. I haven’t heard back from him about what he thinks, but I hope he’s not offended or anything. He was dealing with the divorce and I guess there was more of his life in there than I realized. His wife had moved with their daughter back to Florida, so that stuff ended up in the book. And I hope I wasn’t overstepping, but I don’t think he will take any of that personally. I hope not.

From what I've read from the last time you talked with us, you definitely took a lot from real life for Beverly as well. Why do you rely on real-life stories and then kind of fictionalizing them to a certain degree?

I feel like I just have to know something about what I'm writing about in the simplest terms. If I wanted to write about my friend's life in Colorado Springs and I told him that was what it was going to be about, I would have an obligation to be honest to who he is as a person. But when I veer into fiction then I can create a character that has, you know, more flaws. I don’t have to worry about hurting his feelings.

It seems like veracity – being honest and being realistic – is really important to you.

It seems like veracity – being honest and being realistic – is really important to you.

Yeah, I just find that if there are certain things I can sink my teeth into – even just visiting his house and having a layout of the townhouse he lived in and photos to work off of kind of cemented some reality. When I'm drawing characters, I try to have some degree of a defined space that’s truthful to perspective and proportion. So when I have that as kind of a jumping-off point, it just makes the whole process a little bit easier. It is good to start with if I feel like I know someone very directly. The first half of Beverly was based more directly on real events and then as I got more comfortable they became more rooted in fiction. And then Sabrina is very much a fictional story just with some elements of things from my life to help it along.

I was going to ask you about your process, because I know you don’t generally work from a formal script. But it sounds like the first step of the process for you is just developing the research and the background material that informs the stories in the first place.

Yeah, it starts very much in my head, not defined and it doesn’t really start from a visual place. I noticed, in the process of working on these increasingly longer stories, that the drawing gets very boring and routine after a time. The only way for me to avoid burnout is to be really invested in the idea. More often than not, if I’m out in life and an idea pops into my head, it’s not something visual, it is something that is more narrative.

Why does the drawing become boring and routine?

I think on the cartoonist's end it’s very repetitive. So there is a tendency to feel like you need to shorten and edit things, because you’re bored and you have all that time to doubt it and to doubt yourself and to want to edit. And I think that’s a negative inclination and that’s why in this book I tried to have more breathing room and to not feel so stifled by that. What might have taken you a month to draw will take five minutes to read.

I’m curious about how your life led you to comics in the first place. When did you first develop your interest in the medium and what creators influenced you?

I started a bit late. I was 18 and a high school friend and I were both going to community college. He was drawing crude notebook drawings and something about that appealed to me. I think ever since then, I have been trying the process of moving away from where I grew up and changing the way – Well, basically what is behind this whole interview is that there is a ton of uncertainty and a ton of negative feelings that have come up in the past year or so. And it makes me very conflicted about even doing an interview, taking in any kind of attention or validation that might come from what I’ve made, because it’s just wrapped up in a lot of self-hatred. And that’s another thing that has been kind of hard to get over recently. And somehow making art is very comfortable, or very comforting to me. But also, when I am being my most self-critical, it just seems like this exercise in ego gratification or something.

So I think that's why I'm having trouble answering these questions in a clear-headed way, about even simple things like my process, because in my mind I'm getting tripped up thinking, “What is my process? What does this even mean? What am I doing?” And the silver lining is that I think all of these things will just funnel into whatever this next project is. I think that the little bit of work I’ve started on, and a little bit of notes I’ve jotted down, have all been centered around these feelings. And I feel like there might be something healthy and relatable in doing that and just being able to share that with other people. So that is kind of the mode of thinking that is keeping me working these days.

Where do you think that self-hatred you just described arose from? Is that a more recent thing or is that more deeply rooted?

Where do you think that self-hatred you just described arose from? Is that a more recent thing or is that more deeply rooted?

In the culture there’s a moment of reckoning now about who we are. I think all of these things lead to self-reflection and just taking a good hard look at yourself, which can be very painful and scary. In the case of myself, I can look at just what I see as a lifetime of kind of a misspent youth and periods of total inaction and depression and negativity. But then I see where my life is at now. I'm about to get married and I'm in a really great, healthy relationship. These are things that lead to really interesting discussions with me and my fiancée. I feel like hopefully that’s the best spin I can put on this, that I’m just working through personal things and then maybe come out the other end with a new perspective.

I thought there was an interesting parallel between Tyler in Beverly and Teddy in Sabrina in that they’re both these deeply repressed, isolated characters who seem to have great potential for violence, but neither of them really wind up acting on that impulse. And, in fact, you have both of them wind up their stories trying to act on kinder impulses. What interests you about that character type and, more importantly, what interests you about making them hold themselves together instead of losing it?

Well, I guess they’re probably the closest thing to a stand-in of how I would act in a certain situation or something that I would find kind of relatable. A lot of the characters in Beverly I’m looking outwardly, but some of the things that Teddy or Tyler are dealing with internally, I’ve struggled with as well – not so much the violence. Now that it’s out there, there’s a certain kind of exposed feeling that makes me a little bit more self-conscious and stifled, realizing that whatever you’re doing is a comment on you, as a person and your psychological makeup. I still feel very conflicted about that and don’t feel entirely comfortable with that process.

Just the process of letting that work out into the world, you mean?

Just the process of letting that work out into the world, you mean?

Yeah, I guess it should feel cathartic in a way or feel like I’m communicating with friends and strangers about hopefully shared experiences, but it’s hard to see it that way. I’m trying to learn how to see it that way. It’s not a good feeling to be overwhelmed with shame about making books, you know, because I’ve pushed myself to a point of exhaustion at times and then I can’t really feel good about the end result, so that’s been a bit of a challenge.

So do you tend to pay a lot of attention to the reception to your work, just to see how people are reacting to you making yourself vulnerable in that way?

Yeah, it’s funny. I do read reviews and the comments and stuff. It’s not even so much that I’m hypersensitive to a bad review or anything like that or can’t take criticism, because I could see the criticism of both of these books easily and can understand it. But there’s a curiosity factor where I want to see what people are saying. It’s a little tricky.

What do you think it would take for you to overcome that shame and that discomfort with putting that work out there? Is it just time and having people accept you and your work?

I really don’t know. I can hope that it’s just time and continuing just to focus on what I’m doing. The most comforting thing in the world still is when I have a page on my desk that I’m invested in, that I can focus on. It’s very much art therapy, so all I can hope for is that there’ll still be the impulse to do that because it’s very helpful.

Well, I finished the first draft in about April of 2017 and didn’t want to publish it. I cancelled the publication for a month or so. I told Drawn and Quarterly I just couldn’t do it. It was something about that particular story. There were a lot of things I was troubled by, but then I came around and spent the summer into the fall cutting things and re-editing and adding scenes. We finished the book around December, the design and the covers and all that.

What was it that troubled you so much about it last year that you put it on hold?

Just the personal loss of faith in it. I thought it was way too negative. Since I started it, in a nutshell, to some degree it felt like this Pandora’s box that I had opened that would really cause me a lot of trouble and it was hard to keep up faith that this was even working as a story. I had to kind of work on this false confidence for a long time, kind of running on fumes. And then when it was all said and done, you know, Trump’s president and everything just seems evil and negative and awful and I thought: I don’t want to put another evil, awful thing into the world. At least, that was my perception of it at the time.

The book really has so much resonance in the Trump era too. I assume when you really started writing and working on this it was maybe even pre-Trump campaign?

Yeah, certainly. I was one of the deluded, out-of-touch people that didn’t see it coming until it was too late, until election night essentially, when it felt like the world was turned upside down and there was this whole other side of America that I’m not connected to, living in Chicago. But the book was more than halfway done at that point, so things kind of unintentionally linked up with what’s been highlighted during the Trump administration. Like the obvious thing is fake news and conspiracy theories and the publicity that people like Alex Jones have been getting. [Jones] was a pretty public figure before then, but this was very much a niche interest of mine.

Yeah, you do a deep dive on that conspiracy theory stuff and there are those long passages of the radio show that Teddy listens to. What was your research process like for that? It feels so real.

Yeah, you do a deep dive on that conspiracy theory stuff and there are those long passages of the radio show that Teddy listens to. What was your research process like for that? It feels so real.

Thanks. I mean, as much as I hate to admit it, it wasn’t hard. I felt like I was aware of what’s been going on in those circles, kind of the conversation. There’s more of a curiosity in seeing what the newest conspiracy theory was because what you realize when you start to follow those things is that everything’s a conspiracy for them. It becomes actually kind of predictable. When a big event in the world would happen, I could sort of think in the paranoid kind of conspiracy theorist’s mind about what this actually means—because everything means something.

Sabrina is only your second work, except for a few self-published books, and I was really struck by how little your visual style seems to have changed since Beverly. Usually with a younger artist doing his or her first few works you can really see them kind of figuring things out, but you seem like you’re pretty locked in. Do you feel pretty settled in your style? Or were there new things you were trying with Sabrina that might not be immediately apparent?

Yeah, I wouldn’t say it’s a radical departure or anything. I think I sort of would fret about style, and to put the visuals first seems like a good way to learn what you’re doing when I was a little younger and more uncertain. Now when I have an idea it’s about a story and not about some new visual style I can experiment with. That’s just kind of a way to help me work because if I’m worried about the story, that’s one worry. If I’m worried about readability and all those kinds of things, that’s another kind of concern. And if I’m also worried about what’s just going to look really badass on a gallery wall or something, it’s just too much. It’s helpful to just think in grids and structure. I don’t foresee myself making any radical departure from that, but again, who knows?

You mentioned grids, which are such a big part of your work and your style, and I was going to ask you what you’re going for in terms of communicating through the grid. But it sounds like the grid is more of an organizational structure for you, even more so than it’s intended for the reader. Am I reading that right?

Yeah, exactly. Part of working on these comics is learning things about your own personality and your taste. As much as I had aspirations of working in a certain way – you know, you look at other artists and all these different approaches you could possibly do – but you do just kind of have to stick to what works for you.

You mentioned that there were some certain styles that you saw yourself working in at some point. What were you envisioning?

I could think of so many examples. I just read Anna Haifisch’s new book and you look at it and go, “Oh man, that just looks like fun and looks so inventive and so filled with life.” I think even if I were to sit down and try to do that, Anna’s doing what works for her and I can’t really tap into that. If I was a musician or something it would be like these are different genres we're working in entirely. Some people can seamlessly weave between genres and other people kind of follow this one path. I think I’m realizing that, for better or worse, I’m not going to be a virtuosic artist that can just interpret all these things and put my own personal take on it.

So what are you working on now? What’s germinating for the next project?

It’ll be another long book of some kind and as it's already developed in just the first few pages it's more vignetted the way Beverly was. The restriction of working on Sabrina, sticking to this one story with minor digressions, I’m glad I worked in that way. But now I think I’m going to work on something with a lot of characters and, again, trying to infuse it with just something different. Not necessarily lighter or anything. Again, I don’t know. There is kind of a good feeling when you start something new, where you feel like there’s this potential. It’s always the best part of working on something, where you feel like this can turn into anything. So hopefully I can just kind of keep that momentum going. That’s all I’m hoping for with everything that I’m doing.