Today, we are publishing an English-language version of an article that originally appeared on the Italian comics website Fumettologica. It's a roundtable discussion featuring colorists from various countries, talking about their process, how digital tools have changed the profession, and more.

Matt Hollingsworth: I think there's a fundamental historical misunderstanding of what was going on with coloring when the transition to digital was happening. At the time before I made the transition myself, I was doing mostly color guides, like most colorists. These color guides were just that, guides. These were handed in and then handed off to someone else to interpret. Earlier on, this process was more primitive. But around the time Oliff was doing his thing on Spawn, the people interpreting our color guides were called separators and they were doing that work on computers, same as Oliff. So, we basically had a middle man between us and the final colors, and they more often than not ruined our work. Oliff had fantastic artists doing his separations. They were amazing colorists in their own right. A lot of other seps studios had technicians and not artists and they often did a bad job on the seps. This is not to say all separators were bad, but the vast majority of them were. Some pages would come out great and you could tell that that separator was good and an artist. Most of us made the switch to computers so that we could do our own separations and avoid having other people destroy our work.

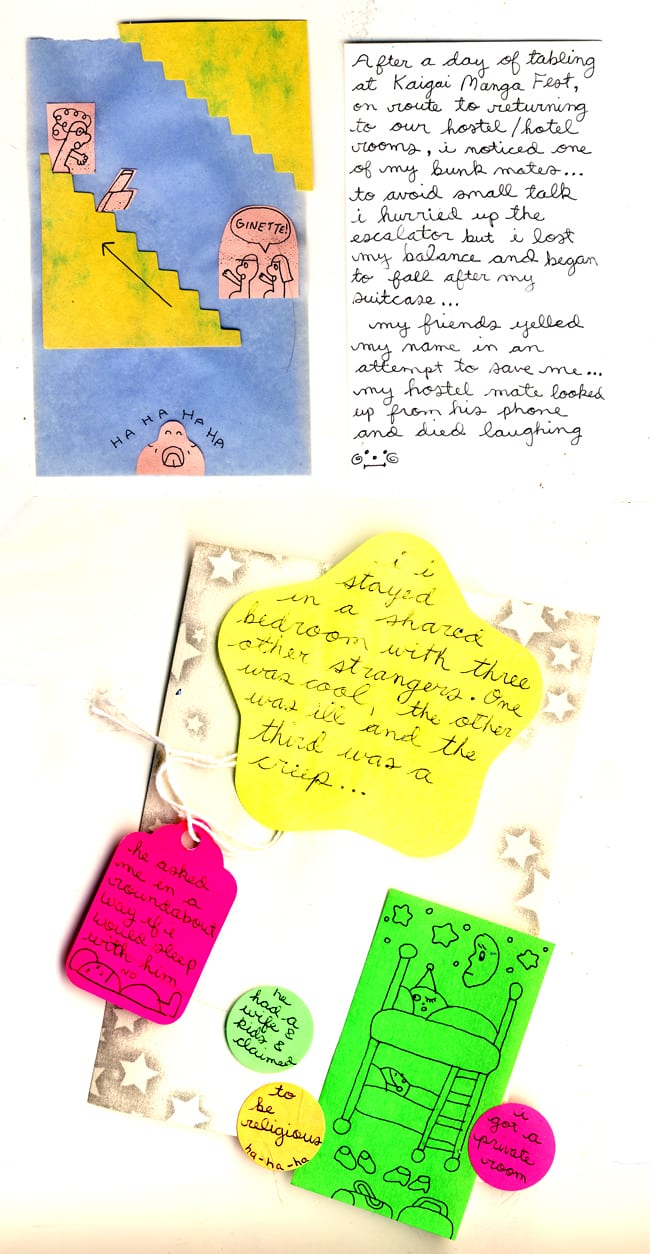

We also have day three of Ginette Lapalme's Cartoonist's Diary of her trip to Tokyo.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—Interviews & Profiles.

The Johns Hopkins Hub talks to Ben Katchor about comics, politics, and cities.

In New York, at least when I was starting out, it was possible to live cheaply. That made a big difference in the amount of free time I had to make not overtly commercial comics, things that you just wanted to make and get into the world. So that's probably easier to do in a less-expensive real estate market. That's basically what cities have become—they're attractive entertainment places for affluent people. If you don't have money, you may be better off in a little town with a garden and less of a crushing overhead.

The Guardian talks to Daniel Clowes.

His characters also often miss things that the careful reader can see. “A lot of what I write about is what someone wants to present to the world, and then what they really are,” Clowes says. “What I play with a lot is the text, which is a lie, and then the image is the truth.”

When asked why he wanted to spend so much time on a single project – the book [Patience] is also his longest, at 180 pages – Clowes is frank: “I did not want to.”

The Huffington Post talks to Austin English.

From the start, it was clear to English that his style diverted greatly from the classic comic book formula. The artist explained to me that the first rule of cartooning, to his understanding, is that the characters must look consistent from panel to panel, from beginning to end. When making his own images, though, English couldn’t resist changing figures from one panel to the next, turning over the visual guidelines he’d just established. “The urge to break the rules is completely irresistible,” he added. “When I draw the comic for a second time I want to make a larger stomach or bigger feet.”

—Misc. For The Paris Review, Aidan Koch adapts a Lydia Davis story.