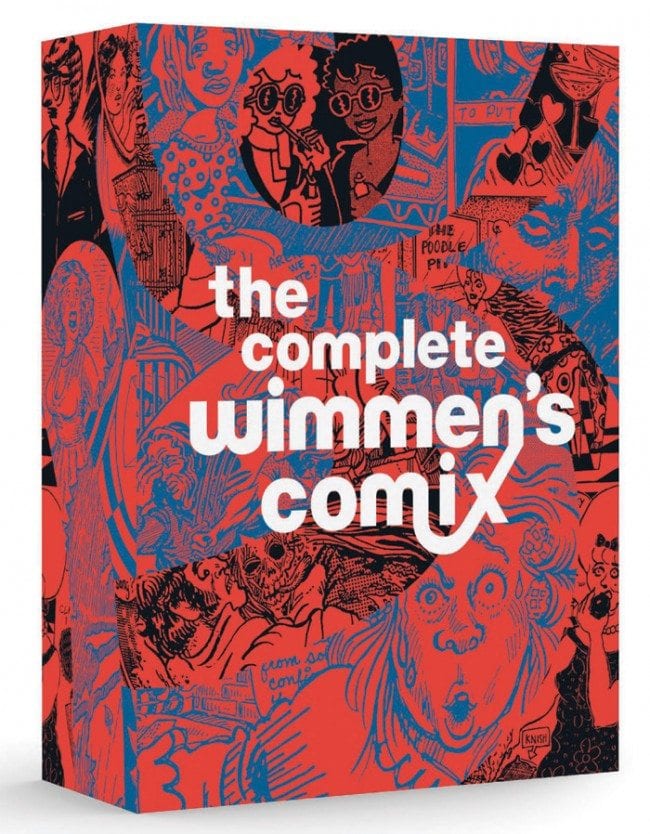

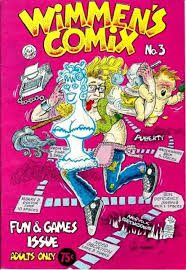

If Zap Comix #1 kicked off the underground comix movement, then over the two decades of its run, Wimmen’s Comix played a key role in shaping the generations of cartoonists that followed. This was a publication that was explicitly political, interested in memoir, promoted women’s voices, and was inclusive in every sense of the world. There was no set style or approach, there was no defined aesthetic. Though a series of guiding principles and beliefs were articulated at its start–and there were many turnovers and disagreements over the years–the actual comic books were never defined by one voice, one style, or one creator.

If Zap Comix #1 kicked off the underground comix movement, then over the two decades of its run, Wimmen’s Comix played a key role in shaping the generations of cartoonists that followed. This was a publication that was explicitly political, interested in memoir, promoted women’s voices, and was inclusive in every sense of the world. There was no set style or approach, there was no defined aesthetic. Though a series of guiding principles and beliefs were articulated at its start–and there were many turnovers and disagreements over the years–the actual comic books were never defined by one voice, one style, or one creator.

Perhaps one sign of the series’ influence is the many creators associated with it over the years who continue to work. Alison Bechdel, Phoebe Gloeckner, and Lynda Barry are three of the most acclaimed cartoonists in America. Carol Tyler (Soldier’s Heart), Sharon Rudahl (Dangerous Woman, Lincoln for Beginners), and Joyce Farmer (Special Exits) have made the best work of their careers in the past decade. And any list of great and influential cartoonists of recent decades that did not include Aline Kominsky-Crumb, M.K. Brown or Julie Doucet would be incomplete. To say nothing of the hundreds of comics and anthologies created and edited by various contributors over the years.

Today women are more prominent in comics than ever. Memoir was not a central concern for a lot of the underground; neither were feminism and women's health, but they have become much more central to cartoonists and to their artwork, and Wimmen’s Comix is a key piece of the history of comics that has mostly been glossed over.

Fantagraphics has just published a two volume slipcase edition of the entire run of Wimmen’s Comix (1972-1992) and It Ain’t Me, Babe, an all-female comic edited by Trina Robbins which was released in 1970. To mark the publication of the compilation, I spoke with a number of the women who were involved in the publication in various ways over the years. Some of them contributed to It Ain’t Me, Babe, others were among the “founding mommies” as the ten original contributors of Wimmen’s called themselves, some contributed to one issue. For some, the experience was important, for others much less so. They remain unique talents to this day with vastly different perspectives and aesthetics and opinions. I’m grateful to all of them for their time and their kindness.

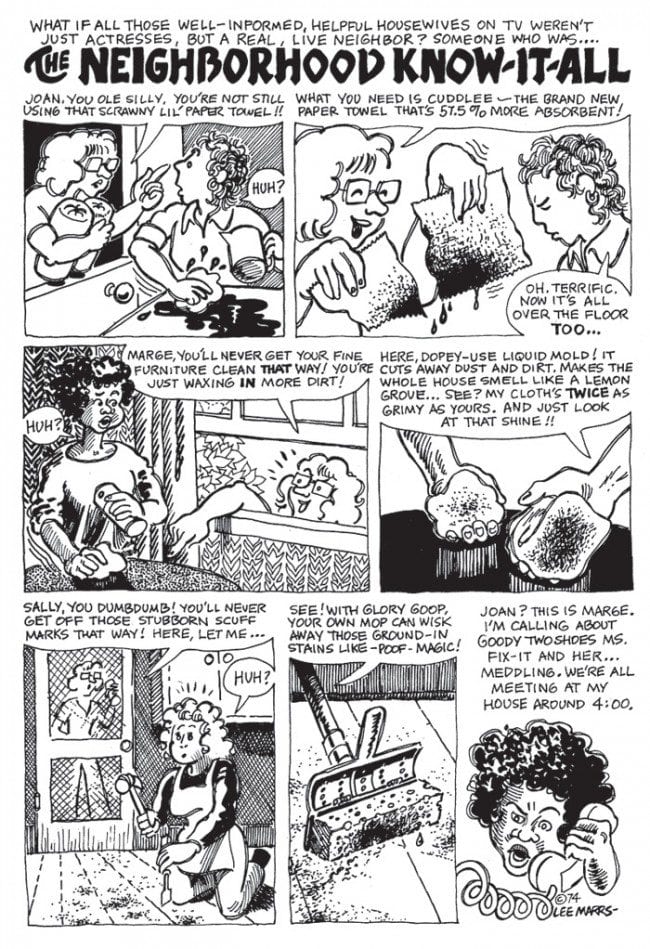

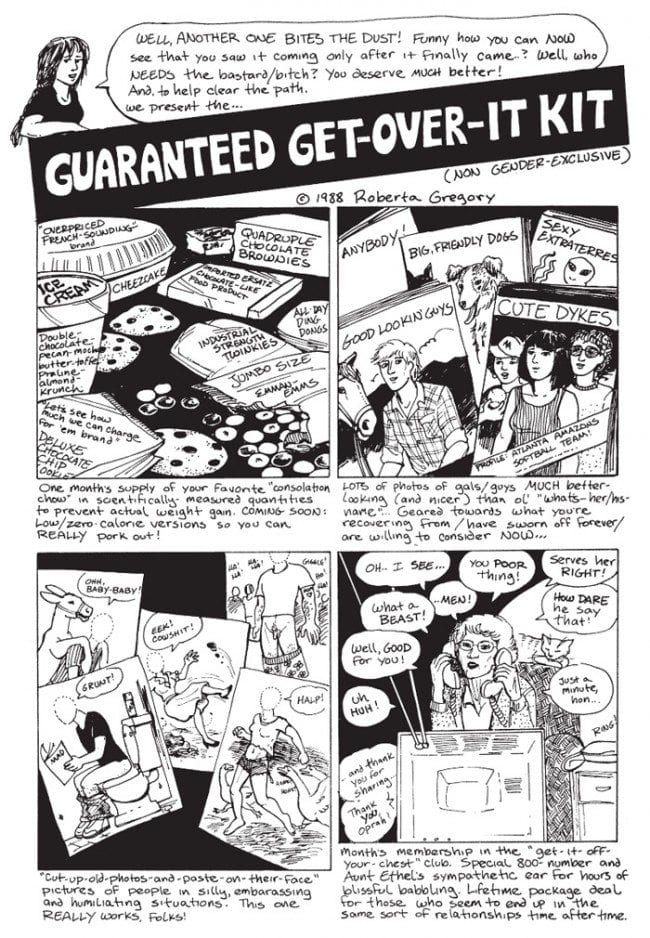

The following article has been assembled from a series of interviews with M.K. Brown, Nancy Burton (aka, “Hurricane Nancy”), Jennifer Camper, Leslie Ewing, Joyce Farmer, Mary Fleener, Shary Flenniken, Lora Fountain, Phoebe Gloeckner, Roberta Gregory, Joan Hilty, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Meredith Kurtzman, Caryn Leschen, Lisa Lyons, Lee Marrs, Barbara Mendes, Patricia Moodian, Diane Noomin, Trina Robbins, Sharon Rudahl, Carol Tyler, and Rebecca Wilson conducted by phone, skype, google chat, and e-mail in 2015 and 2016.

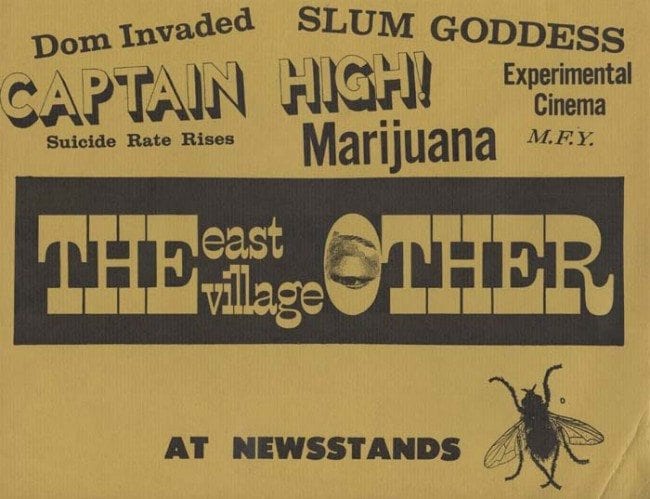

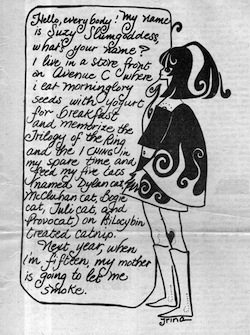

Nancy Burton: I was living with a young poet named Krystyan Panzica on New York’s Lower East Side and altered my name. It was a very inspiring time with a large artist community. I had pictures in my mind that I couldn’t explain, and stories as well, so I began to draw. I believed everyone was searching for their own truth, and comic art, primitive art, local music all helped in my search. I went to The East Village Other and gave them the strip; never asked to be paid. To my knowledge there was not much underground comics around. I traveled a lot so I have no idea how the work was received.

Trina Robbins: In the summer of 1966 I came to New York from LA. I had always drawn and I had gotten really interested in comics. This was when Batman was on TV and everybody was into pop art–of course my style was completely different. Before I even got to New York someone showed me a copy of The East Village Other and it had comics in it and they were about hippies rather than superheroes. It just so happened that my friend Eve Babitz was the managing editor of The East Village Other at the time so when I came to New York I looked her up at The East Village Other office and made friends with the editor and publisher. The first thing I drew for them wasn’t even meant for publication, it was this drawing of a cute chick–I used to draw a lot of cute chicks–and one speech balloon and they published it.

Barbara Mendes: My first husband, Rick Kunstler, was friends with Kim Deitch. We lived on East 1st Street, when Kim stopped by as he was bringing “Sunshine Girl” to The East Village Other before it was even accepted. I began drawing comics for fun; when Kim founded Gothic Blimp Works as a comics supplement to The East Village Other, he invited me to be in it. That was my debut in underground comics. I did several back covers for the Gothic Blimp Works. I wasn’t into cartooning, but it wasn’t a leap. I was just an artist encountering an art form. When I saw Kim and the comics, I saw Daumier and Toulouse-Latrec. Those guy’s posters were popular art. Now those posters are big art objects–but at the time, they were shlock. Comics back then were schlocky culture. They cost a buck. I was so thrilled by the prospect that I could do color. Kim taught me to do color separations on acetate. I always saw comics as a fine art mechanism. All my art exists to get a message out to improve the world, and comics are a great medium for that. Comics are narrative by definition but fine art isn’t. Narrative, message, story–all that is frowned upon in contemporary fine art. Comics are an even more natural fit for my narrative bent.

Trina Robbins: I’d come from Los Angeles where we were wearing outrageous clothes and I thought what they were selling in the East Village was rather boring. I rented a storefront and opened a boutique and because I was friend with The East Village Other crowd I made some clothes for them. I made Walter Bowart, who was the editor, a jacket out of an American flag, which became iconic. Everywhere he went, he wore that jacket. When the FBI wrote about him, they talked about his jacket. [laughs] So I knew these people and I was making clothes for some of them so instead of giving me money, they ran this comic strip for free that advertised my store. It was called “Broccoli Strip” because the name of my store was Broccoli. It was very psychedelic. Most people didn’t even know that it was an advertisement for a store. They thought it was a comic strip. I gradually started doing more comics for them. Then Vaughan Bode was the first editor of Gothic Blimp Works and he invited me in. I missed the first issue but I was in every issue after that.

Barbara Mendes: “Willy” was a nickname that Rick gave me; true to the ever enduring male wish to diminish women, few men have been able to cough out the word Barbara. Bobbie, Boo, Willy, Baby– anything but “Barbara.” Everyone called me Willy back then; it was my nickname in that era. I don’t see how you could look at one page I ever drew and think that a man drew it. Isn’t it kind of obvious that I’m a woman artist? I didn’t ever do it deliberately to make people think I was a man. I never thought they would. In retrospect, it worked very well.

M.K. Brown: I moved to the Bay Area in the '60s. I had been traveling in Mexico and arrived in San Francisco to see if I liked it. I was about to fly back to Connecticut but had an immediate affection for the city and stayed. It was a wonderful time to be there. I was living in North Beach with my husband B. Kliban and our daughter, Kalia. It was a busy, creative time. I was showing paintings in several galleries and entering museum shows and beginning to sell cartoons to magazines like The Realist and Playboy. I began to meet other artists whose work I admired a lot–Robert Crumb, Victor Moscoso, Bill Griffith, Spain, Diane Noomin. There weren’t that many other women cartoonists available to me at the time, probably because we were all so busy with families and our work, I know I was. The sixties and seventies were exciting in San Francisco: the music scene, posters, politics, underground comics, etc. By the way, this is all beautifully described in The Season of the Witch, a fascinating book about that period by David Talbot.

Trina Robbins: It was really weird. Within the space of about a year most of the New York underground cartoonists packed up and moved to San Francisco. Yellow Dog, which was a comic book anthology, was being published there. Crumb was there doing Zap. In New York we had Gothic Blimp Works, but we didn’t have any comic books and that was really revolutionary. The concept that you didn’t have to do a comic in an underground newspaper or in a tabloid but you could do it in a comic book. We’re so used to it now, but it was revolutionary then. The printer who published Yellow Dog was in San Francisco and it just seemed like the place to go. I thought of it as a lemming-like migration because we all just headed west and then unlike lemmings we stopped at the Pacific.

Barbara Mendes: Everybody moved to San Francisco at the same time. The summer of ’69, I think. We were apartment hunting and ran into Kim [Deitch] and Trina [Robbins]. They were a couple and we ended up renting a house with them on Edgar Place. Now I’m really in the underground comics world because I’m living with Kim and Trina and there are underground cartoonists parties. That’s when I contributed to Gary Arlington’s comics. I had the back covers of Boogeyman and Insect Fear. Everything was moving along great. Kim got me in and I was good. Not only that, but my Boogeyman contribution story was deemed too gross. [laughs] Meantime, Trina and I are both pregnant. She was pregnant before me. This is around the time that she split from Kim and the whole feminist thinking came to the fore. I did have my consciousness raised by Trina. She and I basically co-edited It Ain’t Me, Babe. I had the back cover and a story. That’s when the split came and we became “the women” and they became “the men.”

It Ain’t Me, Babe

Trina Robbins: I get to San Francisco and I discover, isn’t this wonderful we’re all here doing underground comics–well, it wasn’t. The guys didn’t include me. Later there were so many [cartoonists] but in the very early seventies, the first few years, it was a small group of guys and they all knew each other. It was a clique. Most of the comics in those days were still in anthology form so if they were going to do a comic, they’d call each other up and say, I’m going to do a comic, do you want to contribute six pages or four pages? Nobody called me. Nobody invited me into their books. Nobody invited me to their parties. The underground newspapers in the Bay Area were still carrying comics and they were a whole other group. They were much more open and that was wonderful because I wanted to draw comics for somebody. Underground newspapers had just started and if they were going to do an article, I’d read the article and on the spot, draw an illustration for it. I was getting published and I was drawing for people who wanted me to draw for them.

Meredith Kurtzman: I was at the School for Visual Arts. I had one comic published in The East Village Other, but that was it. I can’t remember how I got involved with It Ain’t Me, Babe. My father knew Trina and Kim Deitch and I remember visiting them when they lived in a storefront on Ninth Street. We weren’t great pals or anything, it was more my father knowing all the underground comics people. They’d come to our house for dinner sometimes. I don’t think there was anyone else in that first issue who I really knew.

Trina Robbins: Someone showed me what must have been the first issue of It Ain’t Me, Babe, which I had always thought was the first feminist newspaper on the West coast, but I later learned that it was the first feminist newspaper in America. I phoned them and said, I’d like to work for you. There was a be-in at Golden Gate Park and we met at the be-in and I wore a t-shirt that I had designed that had this strong and angry looking heroine and said under it “super sister.” They thought it was wonderful. They were in Berkeley so after that every three weeks or so I would show up at Berkeley and be doing drawings for them. I was also doing a lot of their covers and a comic on the back page. After working with them for a while, they gave me the moral support to say, I can put together a comic book.

Lisa Lyons: As I remember, Trina called and asked if I’d be interested in taking part in It Ain’t Me Babe. No email or texting back then. How did she hear about me? I don’t know. Everybody knew everybody, or at least everybody knew somebody who knew somebody else on the Left in the Bay Area. I was a political cartoonist for the Independent Socialist Club and its newspaper Workers Power, and did work for many anti-war, civil rights, and social justice organizations, including the Black Panther Party, the Free Speech Movement, SDS, the Farm Workers, and the Peace and Freedom Party. My work appeared regularly in Liberation News Service. I illustrated Barbara Garson’s MacBird, which was translated into many languages and became a stage play.

Meredith Kurtzman: I didn’t do comics, aside from that. At all. Everyone thought I should do them but honestly I wasn’t that drawn to it. I never saw myself as a storyteller. I know there were a lot of artistically crazy comics, but I always liked stuff that tells a story. A lot of the underground comics then were really self-indulgent. I liked them then, but a lot of them don’t really stand the test of time too well. It was get stoned and draw. [laughs] I did that too. It was fun. [laughs]

Nancy Burton: Trina Robbins contacted me and acknowledged my work. That’s how I got involved. “Hurricane Nancy” sounded better then changing names every time I changed men. I just liked the sound–no other thought.

Trina Robbins: You have to understand it was never the publishers, it was never the underground newspapers–they just wanted to publish a good artist. They had no problem with me. They never shut me out. Only that little clique of guys. Print Mint said, we’re interested in a woman’s lib comic. I was putting it together and I found all these women who could draw.

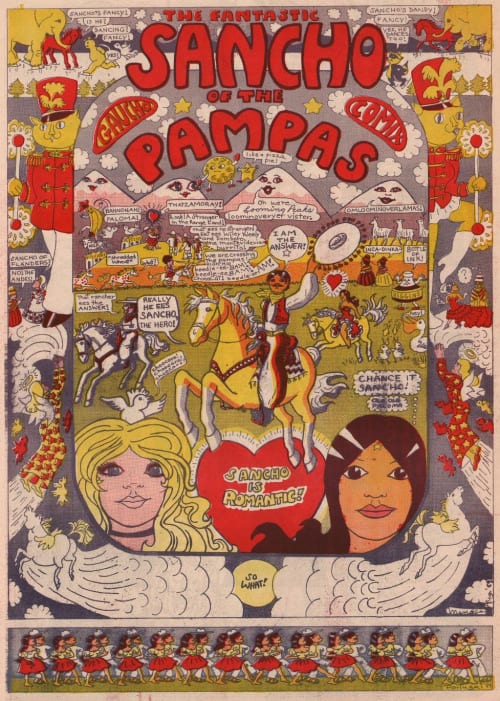

Lisa Lyons: I spent a lot of my time drawing political cartoons on request that involved things like tanks and war imagery and people with picket signs, and when Trina said it was a feminist project and I could do anything I wanted, I was in! Women’s Liberation was newly resurgent at the time, but I’d been raised as a feminist and thought this would be amazing. I was a big fan of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, but disliked the depictions of women in most conventional comics and in work like R. Crumb’s. What an amazing opportunity to work with other women on a women’s comic!

Trina Robbins: I had the book put together, I just had not done the color separations. I found out that this guy named Ron Turner who had published one book about ecology wanted to do a women’s liberation comic. I phoned him and said, "hi, this is Trina Robbins, I hear you want to do a women’s liberation comic, I have one completely put together." He came right over with a check for a thousand dollars, which in those days was an enormous amount of money. I did the color separation for the cover and afterwards the Print Mint guys–who were very nice–said, why didn’t you give it to us? I said, well he came right over with a check. I did my next two comics with Print Mint, so I stayed on good terms with them, too.

Lisa Lyons: My experience working on the comic was brief. I went to a meeting in San Francisco of most of the artists, and met Trina for the first time. As you can see in the group photo, three of us were pregnant, and Trina had just had her baby. It was fantastic sharing so many interests. I did my two pages and sent them in, and not too much later my husband and I moved to Detroit where my tank drawing resumed. Little did I know then that It Ain’t Me, Babe would have a life of its own! My two pages were different from everyone else’s because I came from artistic influences like Barnaby and Hilary Knight and Ernest Shepard, and my focus was already, in 1970, on the inequality between the rich and the poor. We lived in a poor area of Oakland, where the gardens really looked like the one in my cartoon.

Trina Robbins: I don’t know if you know much about the bizarre and neanderthal method we had for doing color separations in those days but you had the black and white art on a nice heavy paper. Then you had transparent plastic overlays and each one was a different color. You did it with zipatone, which I don’t think exists anymore. I did the color separations for the cover and gave it a reddish purplish background and then when it was done, I threw away the color separations. It didn’t occur to me that I would need them again. Then it needed to be reprinted and Ron Turner came to me and said, can I have those color separations? I had to do them all over again and since I hadn’t really liked the purplish color, I made it bright green. That’s how you can tell the first edition from the second edition.

Wimmen’s Comix

Trina Robbins: It Ain’t Me, Babe did well and got reprinted so Ron wanted to do a regular book. It Ain’t Me, Babe was named after the newspaper and I didn’t want to do another–it had been a one of a kind. When I did It Aint Me, Babe I wanted to produce the best comic that had ever been produced. Better than anything that the guys did. Of course it wasn’t. It was great, it had some really well drawn stuff in it, but it wasn’t the perfect magnificent statement that I wanted it to be. At this point I knew Patti Moodian and a lot of people in comics, not all of whom were horrible to me. [laughs] The clique never accepted me, but more people were doing comics. I don’t think Patti had done any comics yet, but she was working at Last Gasp. She knew Ron wanted to do this book so she called a lot of women together who like me or Lee Marrs were already doing comics or women who were part of the comics scene. She got together a group of ten of us. We met at her cute little cottage in Bernal Heights or Noe Valley in San Francisco and we formed Wimmen’s Comix. The title is funny because we just didn’t know what we were going to call this book and at each meeting we’d say, what shall we call this women’s comic? Then we realized that’s what it was. It was Wimmen’s Comix.

Patricia Moodian: I never worked at Last Gasp. I was an independent artist and agreed to let them print my work for a dollar amount, and I retained all copyrights. I was the first editor simply because I took the initiative to do the work it took to get a publisher and gather together the women who would be interested in such an opportunity. I explained to the publisher that I wanted to see a different woman be editor of each and any other other issues after I moved onto the other things I wanted to do with my life.

Lee Marrs: I brought the first story for Pudge, Girl Blimp to Ron Turner. I was taking this around to Print Mint and Rip-off Press and all of them. Turner said that he was interested in doing the book, but I should get together with this bunch of women because they were going to put out a book. Pat Moodian was corralling a bunch of women together to put out a book. I contacted her and there was the first meeting was already scheduled and so I showed up at the first meeting.

Lora Fountain: Since my husband–Gilbert Shelton–is a cartoonist, I got to know many cartoonists when we moved to San Francisco in the early 1970s. I can’t remember how the idea of Wimmen’s Comix came about, but as I had always drawn for pleasure since my childhood, I thought it sounded like a good idea.

Patricia Moodian: Initially, I took some samples of women's comix work to Ron Turner to look at, and to discuss the possibility of letting women into the all male club of cartoonists. He did not seem interested in even looking at the work of the women I had brought to him, and at that time he did not seem to be considering this as a serious business decision. I gathered together a few of the women cartoonists and comix artists, and we organized to get other cartoonists to back us to get women a chance to publish a comic, and show we could do the work, and show that it would sell. Gilbert Shelton, of Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers fame, did say at that time that he would put out an issue for us if Turner did not. Shelton was a true gentleman. Eventually, there was pressure on Turner from the cartoon community, and Turner called me saying he was making out checks for me to distribute, as editor, to whomever I wanted to include in an issue of all women artists. The women did not do this alone. The cartoon community worked together as a family. Spain, Larry Todd, Trina Robbins, and many others were strong in bringing our community together to help each other. If you notice on the front cover of the first issue is the logo of the International Cartoon Workers of the World.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: Spain Rodriguez and Kim Deitch had come to visit Tucson, Arizona, where I was finishing art school and we had a mutual friend. I had started reading underground comics and thought it was really interesting–especially Justin Green’s work. I really saw how I could work by seeing his work. I could never imagine myself working like Robert [Crumb] or Spain, but Justin Green set me thinking that I could put my crazy drawings and my stories together. I moved to San Francisco when I finished school because most of the cartoonists I knew were there. At that time Trina Robbins and Pat Moodian were starting to put together the first Wimmen’s Comix. I went to one of the first meetings and I got my first story published in the first issue.

Sharon Rudahl: I helped start an underground newspaper called Takeover in Madison, Wisconsin before I moved to California where I was working on a paper called The Good Times. The movement was breaking up and falling apart and newspapers were closing. Just as all that was happening Trina was recruiting artists to be in Wimmen’s Comix. She knew I was an illustrator and occasionally did panel cartoons for the newspapers. I had never really drawn narrative comics at that point but I knew people who did–particularly an artist named Guy Colwell who was insufficiently appreciated. He was really was one of the fine artists of that period. When I was in art school I hit this fallow period where it was all black canvases and all white canvases and cubes and I never could figure out what I was looking to do until comics came along.

Lora Fountain: I had worked as a counselor in youth clinics in the Los Angeles area while I was at UCLA and felt strongly about the right of women to have access to safe, legal abortion. It was my experiences with young girls who came to the clinic for abortion counseling that gave me the idea to do the story, “A Teenage Abortion.” I’ve always been militant about women’s health issues, and Wimmen’s Comix was a logical outlet for me before I moved on to other media.

Shary Flenniken: You might say I was there at the beginning. I made a choice not to be a part of it. They wanted a physical studio when this started. That’s what I remember, at least. I’d been working with The Air Pirates–Dan O’Neill, Ted Richards, Bobby London, Gary Hallgren and some other people who came and went. I was really peripheral to that for a long time. We were all living and working together in a couple of different locations. Bobby and I got married and we went to New York and then to Florida and then we came back to San Francisco. That is when Wimmen’s Comix was being formed. I was trying to get out of San Francisco. Some of the women might have felt dissed–I don’t know. I know that I didn’t seem very supportive. One of the reasons I wanted to leave was that everybody was just so emotional at that time. I don’t know how else to explain it, but there was a lot of judgmental stuff going on. That’s an artistic scene for you. I wanted to live a different life than that.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: I met Diane Noomin at a party and instantly liked her. She had a sketchbook with her and I told her we were putting together Wimmen’s Comix and she came to the next meeting. Then I took her to a party where she met her future husband. Our lives were profoundly connected and influenced by each other. Our attitude about ourselves was very different from this heroic women’s figure. We were more into self-deprecating autobiographical humor.

Caryn Leschen: Aline’s work was a huge inspiration. I was like, I don’t have to draw conventionally, I can just draw the way I draw. Her stories were so relatable because I grew up very close to where she’s from. I don’t know Aline very well, but I know Diane and they’re both Jewish women from Long Island, basically like I am. I come from a long line of New York Jewish wise-asses. Trina is also a Jewish girl from Queens. She was usually more into goddesses and mythology rather than everyday life—but in real life, I connected with Trina’s energy; her ability to express herself and do her work still inspires me to this day. She was a kind of mentor to me and has always been very encouraging.

Patricia Moodian: Really it was easy to find the women to participate. There were talented and able women everywhere, chafing at the bit to get a chance to show they could do such amazing work. I did make the calls, have the meetings at my humble abode, and dealt with Turner. The brilliant and legendary Trina Robbins had already published the first all-women comic, and I was very motivated by all that she taught me.

Sharon Rudahl: When I was still in Wisconsin I saw It Ain’t Me, Babe and I was just beginning to stumble onto feminism as a concept. When I saw It Ain’t Me, Babe, to be honest, I was disappointed, but when Trina and I started talking about Wimmen’s Comix it seemed like it was more open. If I wanted to do something political I could, if I wanted to do something philosophical I could.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: Justin Green was the first autobiographical graphic novelist and everybody that came after should pay homage to him. There was a feminist mentality at that time that women should be heroic. Some of those women were raised on Wonder Woman and stuff like that which I couldn’t relate to. I was raised on Jewish stand up comedy and my work basically came from that mixed with a fine art painting background.

Rebecca Wilson: I hadn’t thought of comics as dealing with subject matter that I was interested in until I saw underground comics like Zap, It Ain’t Me, Babe, The East Village Other/Gothic Blimp Works. In 1971 I had dropped out of college and was staying in a squat in Cambridge with some other friends who also dropped out of Boston University when Mark Salditch and I did a comic called Commie Comics: Read by Reds Everywhere. It was a tabloid-sized newsprint black and white comic with a two-color cover. We were both involved in politics, as everyone was in those days. I had been a teenager in Akron, Ohio so I was near Kent State when the students were shot. My brother is Canadian because of the Vietnam war. It was impossible not to have been affected by the war. That really politicized everyone in those days.

Sharon Rudahl: Everything that made me want to do art from the time I was a little kid was not only dead, but scorned and reviled when I was in college. Novels had to be boring and meaningless and depressing, but you could pornography or detective stories or science fiction and make them anything you wanted. Genre was the only place people could live. You could live in genre.

Lee Marrs: We all had different aims for it. We saw pretty quickly that there was going to be no money involved, but one thing that was really important to us was that as many women as possible be given this chance. Because we had a venue that could give people a chance to have their work seen, it was important for us to have about half of the book be either beginners or people who hadn’t had a chance to work in comics before. This was a tenet that we held to for the whole twenty years. It was pretty admirable, I think. However by deciding to do that that meant that the book would never be a superior piece of art that could be seen as a classic comic work of art. There would always be work in it that was artistically marginal or had a lame story or whatever. It was a serious decision.

Trina Robbins: I have heard some women say that it did not function as a collective, but it damn well was a collective. We made collective decisions even though there was an editor. There was a different editor for each issue and they only had so much power. We all would meet regularly and look at all of the comics that had been sent to us. From the very beginning we said, we want submissions. Women all across the country submitted comics to us and we would go through all of them and make our decisions collectively. I think we just automatically decided that’s how we would do it. I don’t think there was ever a question. I had gone through being really excluded and Wimmen’s Comix was very inclusive from the very beginning. I really wonder if maybe it’s just that women work differently. I don’t know what it would be like today. There was were collectives and people were thinking in those terms then–but the guys sure weren’t.

Lee Marrs: In those days–this was California, remember–just about everything anybody was involved with was a collective. [laughs] It was a time when all kinds of different systems and assumptions about how things worked were challenged. All of us quickly saw how much trouble it was going to be putting together a book. There wasn’t anybody who thought, “Oh boy, I’ll take over and be the editor and this will be my vision and I’ll be in charge.” It was more like, “This is going to be a goddamn pile of shit to get through and who’s going to take it on?” [laughs] It was almost like drawing straws. We had all kinds of stuff going on in our lives. It was pretty much a matter of who’s going to be a little less busy in the next five or six months in order to put the book together.

Joyce Farmer: It was a cooperative and as a co-op it meant that you had to get everybody involved before you could do anything. While this wasn’t really that difficult, it could get complicated. Your story and artwork needed to be acceptable to the group. Wimmen’s Comix had a different editor for each issue so the editor was mainly the person you had to please. Tits and Clits comprised just Lyn and myself so we could make all the decisions ourselves and we only had to talk it over with one another, if that. With Wimmen’s, you had a group that you had to make happy and for me that put a damper on what I was doing.

Joyce Farmer: It was a cooperative and as a co-op it meant that you had to get everybody involved before you could do anything. While this wasn’t really that difficult, it could get complicated. Your story and artwork needed to be acceptable to the group. Wimmen’s Comix had a different editor for each issue so the editor was mainly the person you had to please. Tits and Clits comprised just Lyn and myself so we could make all the decisions ourselves and we only had to talk it over with one another, if that. With Wimmen’s, you had a group that you had to make happy and for me that put a damper on what I was doing.

Trina Robbins: It was a safe place. The core group were Bay Area women and we were friends. We would go out for lunch together. We’d hang out with each other. We’d have parties. We’d have gallery shows. We were really and truly friends. If the male cartoonists didn’t accept me, this was a place I was accepted. This was a place that felt good. We were doing something that nobody else was doing. Gradually more and more women got into comics and doing their own books. Two weeks after the first Wimmen’s Comix somebody brought over a copy of Tits and Clits, which had actually beaten us to the stands, and said, look what they’re doing in Los Angeles. It was amazing that in the state of California at almost the same time women were putting out comic books. I still think there was something in the water. Of course we made friends with Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevly and we all got along great.

Joyce Farmer: Have you ever read the Zaps? They were extremely imaginative but they were male-oriented. I thought of Zap as satire, but a lot of women took it as viciousness against women. In retrospect I still think it was mostly male satirical fantasy, but nobody was what we now call “evolved.” [laughs] We were all batting around in our own little bubbles trying to figure out who we were and what we were doing. This was a time of great social upheaval, as you know. I think that there was a whiff in the air that women needed their say. The culture was accepting of women’s right to speak out, but then there was a lot of criticism when we did. You may hear about the difficulty of women getting into comics, but in my opinion it was fairly easy. Lyn owned a bookstore and she said, “Somebody needs to do a comic about women instead of all these guys being so misogynistic.” And so Lyn and I just did it. We used our own money instead of relying on a publisher. Neither of us had any experience whatsoever, but we could see that there were a lot of underground comics done with very poor writing and artwork and we thought, “We can at least match that.” [laughs]

Trina Robbins: People have always talked about underground comics being so political but they weren’t. The ones that were political stand out–like Guy Colwell, who was very political–but most of the guys were not at all.

Sharon Rudahl: I’m a very self-educated person and my political feelings are very simple. I grew up in the 1950’s in a Jewish suburb of Washington, D.C. and we lived next door to some people who were hiding out from McCarthy. These two little boys weren’t allowed to go to school and they weren’t supposed to play with us. I didn’t realize it was because of McCarthy. I remember overhearing grownups saying, they’re communists. I think that’s the main reason I’ve been a communist my whole life. [laughs] I looked it up in the dictionary and it said communism is a theory that people should share everything. Being a little kid, I was told that’s what you’re supposed to do. A little later whenever people said that black people shouldn’t be locked up and tortured for speaking out and anytime people did something decent, they were accused of being communists. It just kept being reinforced that communism was obviously what I believed in. I now have this distinction between communists and commies. Real communists are boring and bureaucratic and doctrinaire and lock people up too, but commies are the ones that have great views and make great literature and help civil rights movements.

Phoebe Gloeckner: I always hated being known as a “woman cartoonist.” I don’t think I deserve an extra adjective and I don’t want it. Why not go all the way and call me a “middle-aged white female cartoonist?” I’m just a cartoonist. All that other shit is incidental, and may be useful in interpreting my work, but the base value should be “cartoonist.” Or “artist.” Or “writer.” The adjectives are secondary, at best. Wimmen’s Comix had a great purpose, a lot of good came from it, but it was depressing to be in that ghetto.

Joyce Farmer: The Wimmen’s collective would meet and decide what the theme for the next issue would be and who would be editor. I don’t know if they voted on it. I only went to one of the meetings and that was about 1983. I never really knew their methodology. I felt that Wimmen’s was much more politically correct than Tits and Clits. Lyn and I wanted our comic to be entertaining, but more important, Tits and Clits was all about female sexuality and women’s imaginative solutions to our unique challenges. Wimmen’s was much more politically themed, in my opinion.

The only thing that I clearly remember about that issue [#3] is that the people who lived next door to us invited us to go down to Mexico and take acid on the beach and I had to say no because I was editing Wimmen’s Comix. [laughs] We looked at a lot of art. We tried to be kind. I’m not a good editor. I either don’t like anybody’s work or I like everybody’s work. When I teach I give everybody A’s.

Lee Marrs: The group of women was very supportive and warm. There was a lot of dynamics, but their intentions were good. Of course I always enjoyed expressing myself, so whenever you have a chance to do that, it’s a good opportunity. Although the group was different over the years, I found it really inspiring to work with that set of women.

Trina Robbins: Safe space is really the magic word. There were a lot of women who were just starting out at the beginning, but it was a place for them. After the first issue came out, you have no idea how many submissions we got from all over the country.

Rebecca Wilson: I had a friend at Berkeley who was interviewing women cartoonists and Trina had a poster in her apartment that I did for Amorphia Rolling Papers. My friend told Trina, “My friend did that poster.” Trina said, “Have her get in touch with me, we’re always looking for women artists.” I loved San Francisco and the fact that Trina had extended this invitation sealed the deal–I was going to go out there and make comics. I moved there early in 1974 and it was just so much fun. It was a great place in those days. It still is wonderful but it’s lost some of its character now that Mark Zuckerberg lives in my old neighborhood.

Sharon Rudahl: We tried to be very inclusive. Early on there weren’t that many people beating down the door to become a cartoonist so we didn’t have to reject that many people. It was more directing someone–this is wonderful, but maybe you could tighten your story a little bit, or try this. I don’t think that many people were rejected out of hand. The bar was set very low, technically, in many ways. I’m not going to say that there was anything wrong with that. It was very inclusive with no intent to be professional, in the sense of be demanding a lot of technical know how.

Shary Flenniken: I’ve complained about Robert Crumb and Artie Spiegleman before. They were influential and had this ethic that I think–and always did–was really hypocritical. Artie was making a living working for Topps Bubble Gum and Crumb was making a living–producing a product that was financially viable. They were telling other artists not to sell out. Selling out meaning caring about making a living, I guess. [laughs] I thought that was weird. This is where being a female differentiates me. I think that the guys saw their careers differently. I was just happy to have an outlet. I didn’t care if it was National Lampoon or Time Magazine or the Berkeley Barb. The underground cartoonists had a different ethic. I don’t know what the other women wanted, but I wanted to get out of San Francisco. It was crazy, it was difficult, it was distracting. I was paying more attention to the guys than to what the women were doing to be honest. They wanted to be in the game and I didn’t really want to be in the game.

Trina Robbins: We just did it and then we did another and then we did another. [laughs] As lo ng as they were selling and Ron was willing to publish them that was good. Of course it did go bad. What happened was in the first half of the seventies, comics were sold in head shops and they sold very well, but then the head shops closed. Women’s bookstores carried us and we did well there but at a certain point women’s bookstores started closing, too. All of a sudden we had real distribution problems. That was about the time that the direct market started and suddenly you couldn’t buy comic books anywhere but in comic book stores. Those places were run by guys who were superhero fans. They weren’t interested in undergrounds, and they really were not interested in undergrounds for women.

ng as they were selling and Ron was willing to publish them that was good. Of course it did go bad. What happened was in the first half of the seventies, comics were sold in head shops and they sold very well, but then the head shops closed. Women’s bookstores carried us and we did well there but at a certain point women’s bookstores started closing, too. All of a sudden we had real distribution problems. That was about the time that the direct market started and suddenly you couldn’t buy comic books anywhere but in comic book stores. Those places were run by guys who were superhero fans. They weren’t interested in undergrounds, and they really were not interested in undergrounds for women.

Roberta Gregory: I saw underground comix when I was in college, in the early 1970s. It was probably around 1973 that they first came to my attention, though by then I was a big fan of the National Lampoon and I was drawing comics and illustrations for Phil Yeh's humor magazine, Uncle Jam. A friend had a lot of underground comix in her home, (Zap, Freak Brothers, etc.) and they appealed to my irreverent sense of humor, but comic books always seemed to be something mostly created by men. I read a lot of comics growing up since my father wrote for Gold Key comics (and the publisher sent him lots of those comics so we had a lot of them in the house), plus I liked to read Superman, Spider-Man, Archie, and so on. But seeing a comic book that featured women was a huge game-changer. I was drawing and writing lots of stories of my own when I was in high school, and even before, but I never thought anyone would want to read them so I didn't tend to keep them around when I was finished. I really wanted to add my perspective to Wimmen's Comix by contributing, and it had a very welcoming vibe. The women even drew little portraits of themselves in the first issues.

Rebecca Wilson: One of the first things I did when I arrived in San Francisco was attend a meeting of the United Cartoon Workers of America. It was a very contentious meeting. Marvel wanted to get in on the underground comix action by starting Comix Book, which Denis Kitchen was editing. One of the clauses in the contract was that you had to sign your character away to Marvel. The subject of the meeting was whether or not to be involved in this project. Some people were saying it was selling out. Underground comix at the time paid 25 dollars a page if you were lucky and Marvel was paying 100 or 150 dollars a page. [laughs] In those days there was tension between some of the women cartoonists and some of the male cartoonists. Trina and others felt like they weren’t being invited into the books that a lot of male cartoonists were doing, and said, we have nothing to lose by working for real money at Marvel. That’s where I met most of the underground cartoonists for the first time like Jay Kinney and Spain and Rory Hayes.

Phoebe Gloeckner: I’d had work published in other in a few comic books before. I think my first story was in Young Lust, in ‘78 or ’79, when I was still a teenager. I’d read “undergrounds” voraciously since the age of 12 or 13, and was quite aware of all the titles. Honestly, I didn’t really like Wimmen’s Comix [laughs]. I don’t know why. I wish I had some in front of me now, to look at as we speak. I think the idea of Wimmen's Comix was frightening to me personally in the sense that it was a “ghetto” of work by members of a group I’d naturally fall into, and I resented the fact that this division seemed necessary. I would read it and feel depressed because there weren’t many women at all whose work was represented in other comics. When I was finally published in Wimmen’s Comix, I found I liked the women who were doing it and the sense of camaraderie but I didn’t like the fact that that particular comic book was all we had basically.

(Part two is here.)