Frank Santoro here, and it's tag-team time again. I will open the discussion on Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC) 2015, and John Kelly will take over halfway down this page. So... Pittsburgh to Columbus. Three and a half hours, unless your car dies in the tunnel on the way out of town. Ten hours, a rental car, and a speeding ticket only put me 600 bucks in the hole. Thankfully, sales were good at CXC. I broke even!

I would’ve paid to go to this show, though. Like travel-wise, I mean. Beyond expenses folded into exhibiting/selling. You should too. Pay to get yourself there, I mean. Easily the best comics show simply because of its connection to the vast history book of cartooning that is Columbus, Ohio.

I like to tell people who’ll listen: Billy Ireland, Charles Landon (the originator of the correspondence course for cartooning in 1903), Noel Sickles (who corrected course homework for Landon), and Milton Caniff are all from Ohio. These four (more or less) set the foundation of North American and European Cartooning. Everyone from Barks to Crane to Gottfredson took Landon’s course; Sickles and Caniff influenced about everyone else. Ohio. If you didn’t know, now you know. Much of cartooning’s rich history is centered in Columbus, Ohio.

So it makes sense to have CXC here. It does actually feel like the crossroads of cartooning’s past and present. You too can sign up for the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library tour and listen to Jenny Robb, Caitlin McGurk, and Susan Liberator explain how Noel Sickles and Milton Caniff (best buds) left to make their fortunes in New York City while Billy Ireland couldn’t be lured away from his beloved Columbus. It’s a great story and really why the museum exists. Caniff made it big and donated his archives to Ohio State University and then eventually the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum was created due in large part to the the efforts of Lucy Caswell. Read about the museum and listen to Jenny Robb explain the museum’s mission HERE.

I liked the format of the show. Opening night was Thursday. There was a Walter Lantz (!) Studios program over at the Wexner Center. A bunch of wacky animated cartoons presented by Jerry Beck. That was a fun opener. Then everyone milled about and many of us went to eat and drink. Saw the great Jackie Estrada and Batton Lash at the hotel bar.

It was fun to hang out without the worry or pressure of exhibiting the next day. Jackie and Bat really have the best stories and her two-volume (so far) collection of photos from the early days of comic cons, Comic Book People, is like a high school yearbook for comics historians. The next day, Friday, was devoted to panel discussions and other presentations at the Billy Ireland Library & Museum. And then there was a one-day expo on Saturday. Check out the photos of the event HERE.

It was awesome. I’ve never arrived at a show and got to hang out FIRST. It’s always sell, sell, sell because most of us arrive bleary-eyed the morning of the show. Maybe we get to hang out a little bit the night before if you arrive early. But for CXC, the first day of the show was hangout day. OK, panel discussion day. But basically, you could just drop in on a panel or two and then go down into the library and do research.

Gregory Benton took this photo (below) of me researching Noel Sickles. Chris Pitzer called me a nerd. I was fine with that. I was happy to pester Susan Liberator, the assistant curator, to help me pore through the Sickles and Caniff files looking for their correspondence. Oh, what’s that? An unpublished fan letter to Sickles from Alex Toth? Ahem.

Anyways, the panels were great—at least the ones I saw on Friday, like Katie Skelly’s talk about how to play around with "influence." The show itself? Well, I think this video about sums it all up.

Thank you to Tom Spurgeon, Jeff and Vijaya Smith, Jenny Robb, Caitlin McGurk, Susan Liberator, and everyone else involved with CXC. Oh, they had great volunteers. Like actually helpful volunteers. My new favorite show. Ohio. You gotta go.

Now, I am turning over this week’s column to John Kelly. John was also at CXC and can write a better overview than I can presently. As of this writing I am packing for the Lakes Festival in the UK. Check out the details HERE. Please don’t forget I am in the middle of my fundraiser to build a brick-and-mortar schoolhouse for my comics school. Everyone laughs at me when I say that my correspondence school is carrying on a tradition set down by Charles Landon and that I feel a kinship with Ohio cartooning. Whatever. I am still going to do my correspondence courses however I am going to make a schoolhouse—more like a dojo.

Check out the video HERE. Just watch the video. I’m not looking for a handout. Just watch the video. Please. UK here I come. Thank you CXC!!! Take it away, John!

------------------------------------------------------------

Discovering History in Columbus at CXC by John F. Kelly

As befits a festival that mostly took place in facilities owned by Ohio State University, a huge public research university that is also home of the world’s largest comic art museum, the inaugural Cartoon Crossroads Columbus event (CXC) was heavy on capturing the history of the comics art form and its community. I worked in higher education for 12 years and have been to my share of academic conferences and CXC had that feel to me; attendees seemed to be primarily made up of people working in the comics field in one capacity or another. I didn’t see any cosplay outfits or insanely long lines of people carrying stacks of books and seeking autographs by the famous artists in attendance, and there were plenty of famous artists at CXC.

A highlight of CXC, of course, was a tour of the vast Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, which holds more than three million examples of original comic art, newspaper clippings, and rare comics, led by curator Jenny Robb. You enter the temperature-controlled library archives through password-secured doors and find filing cabinets that contain an astonishing amount of comics history that would take years to go through; deeper inside this area is an even more secured large “vault” that holds original Gertie the Dinosaur cells by Winsor McCay and an original Richard Outcault Yellow Kid piece, among other things, including nearly all of Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes artwork. You can read Bill Kartalopoulos’ overview of the collection done for TCJ in 2013 HERE.

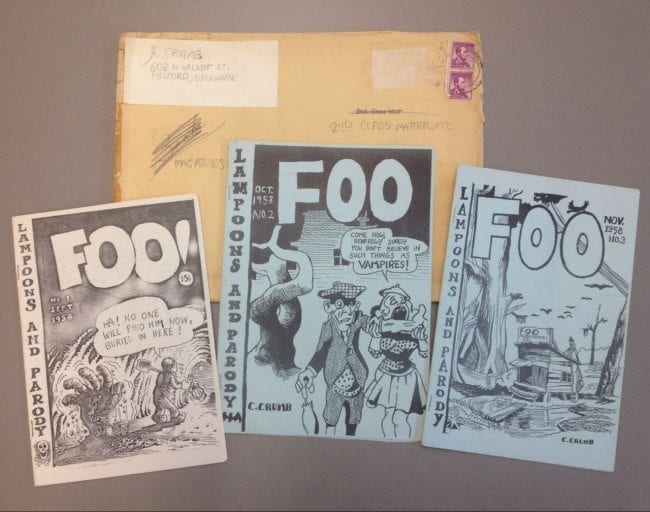

Among the work found in the library are the nearly 10,000 items of underground and alternative comics history donated by the estate of the late Jay Kennedy. Along with Kennedy's own art—and that done by Lynda Barry when Kennedy was her cartoon editor at Esquire magazine—it contains a ton of early work done by people like Art Spiegelman, Jay Lynch, Spain, Justin Green, Bill Griffith, and just about everyone else from the UG era, including copies of Robert and Charles Crumb’s Foo comics (below).

On the tour, Robb showed off copies of early comix fanzines history, including Blasé (by then high-school student Spiegelman), Don Dohler's Wild!, and Skip Williamson’s Squire. In the video clip below, courtesy of the Billy Ireland's Caitlin McGurk, Spiegelman talks about the process of creating Blasé.

And here's a short video showing off the actual contents of Blasé, thanks again to Caitlin McGurk:

Cartoonist Art Spiegelman's early fanzine Blasé from John F. Kelly on Vimeo.

Bill Griffith, who was attending CXC in part to promote his new book Invisible Ink (Fantagraphics), said: "As the man behind the original underground comics price guide, Jay's knowledge of the era was extensive and deep. His collection is an essential part of the museum archives that will provide future researchers with valuable resources. The museum archives are amazing--a real walk through comics history. I could have easily spent days, instead of hours, exploring its files. As a cartoonist, the most fascinating material the museum holds is all the original comic art."

Saturday night’s closing event at CXC was a discussion with Spiegelman and his wife Françoise Mouly, focused primarily on their creation of RAW magazine. Next week’s column will focus on that event, including video of the discussion, which was moderated by cartoonist Jeff Smith. In the clip below, Spiegelman discusses the creation process for the comix magazine Arcade, which he co-edited with Bill Griffith in the mid-1970s.

Art Spiegelman on Arcade at CXC 2015 from John F. Kelly on Vimeo.

One real surprise at CXC was meeting Bruce Chrislip and getting a copy of his extremely limited and hugely ambitious new book, The Minicomic Revolution 1969-1989, which is Chrislip’s often first-person history of the self-published little comic books produced during that era. The book is more than 450 pages long and is filled with short profiles of many of the key artists worked in that form, with many pages of notations and reprints of covers. Beginning with a brief overview of the minicomix roots in the infamous Tijuana Bibles of the 1920s, the book focuses on the publications produced around the time of the initial underground comix of the 1960s and meticulously details work created up until the late '80s, which was around the time Chrisplip’s own artwork slowed down.

Chrislip, whose own work has appeared in roughly four hundred minicomix, worked on the book off and on for the past ten years, inputting much of the history from his memories of those days and using his vast collection of more than 1,000 minis for research. He also interviewed a number of the still living key figures from the minicomix early days, including Larry Rippee, who worked along with Gary Arlington at the legendary San Francisco Comic Book Company in the early 1970s.

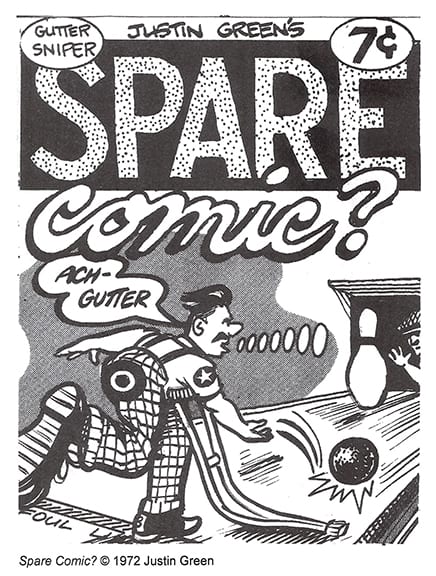

Other sources he used for background included Cincinnati neighbor Justin Green, who Chrislip calls the “first true minicomix artist.” Green produced Spare Comic? in 1972, and “spawned the minicomix movement by being the first in a series of minicomix published by... Alrington. These titles were later popularized by Clay Geerdes, who throughout the 1970s acted as a minicomix ambassador and encouraged many artists to publish their own minicomix.”

“I just wanted to do something simple and subversive,” Green says in the book. “I felt like Martin Luther nailing his manifesto on the church door.”

In true minicomics form, Chrislip chose to self-publish the book and limit the print run to one hundred copies, most of which are already sold out.

“It was a conscious decision from the beginning so I could get it out there quicker to some of my old friends so they could get a copy and read it,” he says. “I thought going through a publisher might take well over a year, so I figured I’d speed up the process by self-publishing. But I printed up 100 of these and when those are gone, I will look in to an actual publisher for the second printing.”

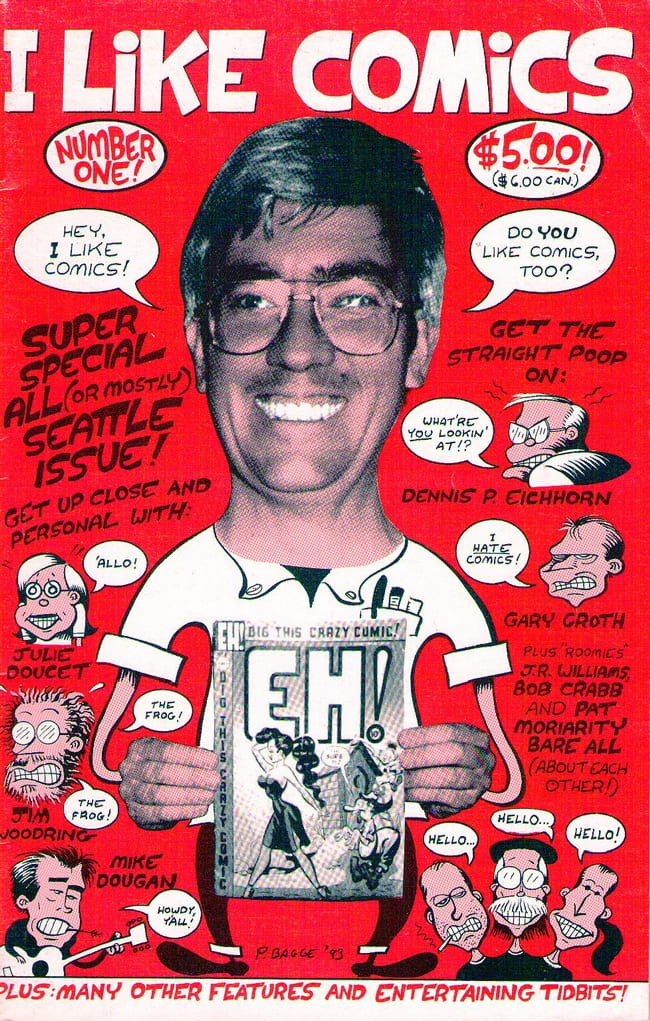

For alternative comics fans of a certain age, Chrislip is also known as the cover boy of Peter Bagge’s one-shot fanzine I Like Comics, a big, thick self-published piece from 1993 that contains interviews with many of the Seattle-based comics stars of the period, including a very funny and long one with the late Dennis Eichhorn. But perhaps it's most memorable for its cover, which featured a photo of a grinning Chrislip head shot with a body done up Bagge-style.

“I think I was at a party at Peter Bagge’s house and [I Like Comics co-editor and former Comics Journal editor] Helena Harvilicz was there too… Peter called me up a little later and asked me if I’d pose for the cover because Helena had said that I looked like the typical comic book fan to her,” Chrislip recalls. “I had been friends with Pete for a long time and we lived in the same neighborhood so I just went over there and we did the photo shoot.”

You can try and order one of the few remaining copies of The Minicomic Revolution by sending $30 to: Bruce Chrislip, 2113 Endovalley Dr., Cincinnati, OH 45244. No PayPal or any of that stuff. Old school.